November 29, 2018

Jonathan Miller's La bohème returns to the Coliseum

Is there a degree of overkill, especially when it comes to a far from adventurous production? Perhaps, although I am well aware of the (alleged) reasons for a company performing the opera so frequently. Do they add up, though? Judging by the number of empty seats at the Coliseum on this, the first night, I am not sure that they do. Might that indicate that it is time to give the work a rest or a new production? Again, perhaps, although what in the present climate would be an adequate substitute for box-office certainty? Perhaps there is no longer any such thing. Is that a bad thing? For a company struggling with declining funding and years of mismanagement - remember the self-styled ‘She-E-O’, Cressida Pollock, granting interviews about how she liked to relax with a bottle of wine whilst wearing her favourite training shoes, at the same time as attempting to sack the chorus? - the answer would seem to be yes. On the other hand, might it ultimately be a prod towards diversity of repertoire, towards taking Puccini as something more artistically serious than a box-office certainty, towards asking whether a performance in an often jarring English translation vaguely ‘after’ Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica is really the best way to ‘sell’ as well as to perform this work to a multicultural audience? Perhaps. We shall see.

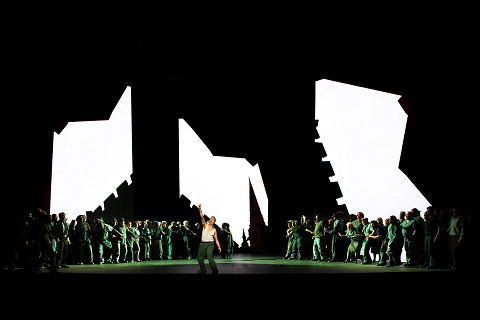

One very welcome aspect of this performance - and possible justification for retaining the production a little while longer - was the opportunity it granted, well grasped indeed, to a young cast including two of ENO’s Harewood Artists: Nadine Benjamin and Božidar Smiljanić. Benjamin’s Musetta is very much her own woman, no mere memory of other Musettas we have heard - or claim to have heard (‘does not efface post-war memories of Dame Ermintrude Heckmondthwike, “Ermie” we called her…’). Not that she was different for the sake of it, quite the contrary, the crucial facets of Musetta’s character coming through bright and clear, but fresh too, very much an acquaintance as well as a reacquaintaince - and a vocal acquaintance too. Smiljanić is likewise an able actor and impressed greatly both as soloist, insofar as possible for a Schaunard, and in ensemble. Likewise David Soar as Colline, his final-act moment something truly to savour. Nicholas Lester’s Marcello was definitely a cut above the average, rich and, where appropriate, ardent of tone, hinting cleverly at far more to the character than we ever officially learn (surely so much of the trick to a compelling Puccini performance). Simon Butteriss’s comedic turns as Benoît and Alcindoro even had a doubter such as I consider the approach (Miller’s, I suspect, more than the artist’s) perfectly justified.

Nadine Benjamin and ENO cast. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Nadine Benjamin and ENO cast. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

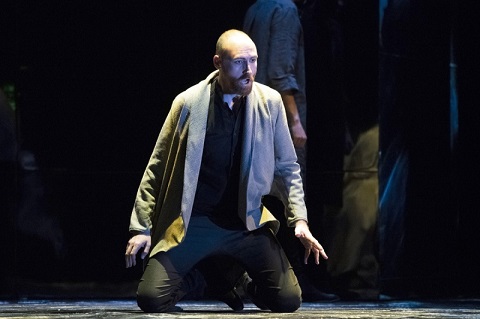

Last yet anything but least, our pair of star-crossed lovers, played by Jonathan Tetelman and Natalya Romaniw, showed themselves (mostly) sensitive artists who could yet project to the back of the largest of theatres. (Alas, the Coliseum remains not the least of ENO’s problems, whatever audience members ‘of a certain age’ might claim.) Romaniw’s Mimì proved perhaps the more moving early on, but that is more likely a consequence of the opera itself than of any great performative disparity; both certainly moved in the final tragedy of the work’s final minutes. If only they had not on occasion - under instruction, I suspect - played to the gallery, treating their ‘big moments’ as stand-alone arias. The real culprit here, I think, was Alexander Joel. His conducting of the ever-excellent ENO Orchestra was incisive and mostly unsentimental, but he seemed incapable of thinking - or at least projecting - a greater unity to each act, let alone to the score as a whole. Of Puccini’s ‘symphonism’, we heard little or nothing.

As for Miller’s production, ably revived by Natascha Metherell - who surely deserved a curtain call - it is what it is. Paris updated to the thirties looks beautiful, occasionally desperate too; Personenregie is keen. As mentioned above, I am more reconciled to its comedy than I first was. Moreover, I rather like - some do not - the glimpses we catch of characters off the set as such, carrying on with their lives. Something a little challenging or interesting, though, would surely not go amiss in the future. As yet, few if any directors seem to have matched Stefan Herheim’s challenge in his superlative Norwegian Opera production, let alone gone beyond it. Will time tell? Perhaps.

Mark Berry

Puccini: La bohème

Marcello: Nicholas Lester; Rodolfo: Jonathan Tetelman; Colline: David Soar; Schaunard: Božidar Smiljanić; Benoît: Simon Butteriss; Mimì: Natalya Romaniw; Parpignol: David Newman; Musetta: Nadine Benjamin; Alcindoro: Simon Butteriss; Policeman: Paul Sheehan; Official: Andrew Tinkler. Director: Jonathan Miller; Revival director: Natascha Metherell; Set Designs: Isabela Bywater; Lighting: Jean Kalman; Revival lighting: Kevin Sleep; Chorus (chorus master: Mark Biggins) and Orchestra of the English National Opera/Alexander Joel (conductor). Coliseum, London; Monday 26 November 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO%20La%20boh%C3%A8me%20David%20Soar%20Nicholas%20Lester%20Bozidar%20Smiljanic%20Jonathan%20Tetelman%20Natalya%20Romaniw%20%28c%29%20Robert%20Workman.jpg image_description= product=yes; product_title=ENO revive Jonathan Miller’s La bohème product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: David Soar, Nicholas Lester, Bozidar Smiljanic, Jonathan TetelmanPhoto credit: Robert Workman

Sir Thomas Allen directs Figaro at the Royal College of Music

This autumn, though, ‘canonic’ composers have dominated the programming. The Royal Academy offered us Olivia Fuchs’ sharply observed Semele for the smart-phone age. And, now, following the Guildhall School of Music and Drama’s presentation of Così fan tutte, the Royal College of Music have similarly elected to test themselves in Mozartian waters with this charming production of The Marriage of Figaro.

In the GSMD’s Così, director Oliver Platt eschewed rococo elegance for rowdier revelry, taking us to a 1950’s hot-spot, Alfonso’s Bar , located near a US naval base in the South Pacific. Sir Thomas Allen plumps for tradition and his designer, Lottie Higlett, transforms the RCM’s Britten Theatre into Count Almaviva’s eighteenth-century chateau, taking us on a tour which starts in the tiny, dilapidated garret where Figaro and Susanna will begin married life, continues in the spacious elegance of the Countess’s boudoir, and finishes amid the graceful trellises of the garden - skilfully arranged to allow for sleight of hand and eye, as the nocturnal intriguers carry out their machinations and reconciliations bathed in designer Rory Beaton’s beautiful moonlight glow.

Both sets and costumes are superb. And, by cleverly opening up the depth of the stage when we leave the shabby attic - with its single bed (will there be room for a double, Figaro ponders?), thread-bare chair and rather forlorn mannequin upon which Susanna’s wedding veil perches expectantly - and enter the stately sumptuousness of the Countess’s bedroom, Higlett emphasises the class tensions and injustices which propel the drama. The colour schemes are beguiling, with Susanna’s simple sky-blue dress set against the rose-gold luxuries of the aristocracy. And, the cast wear their frock-coats and fineries with confidence and style; they’ve clearly worked very hard at the particulars of characterisation and the production has been meticulously rehearsed.

I struggle, however, to say anything of import or interest about Sir Thomas Allen’s direction - other than that he has evidently exercised what must be described as a ‘light touch’. Nothing wrong with that, of course - indeed, we often have cause to lament directorial dabbling and conceptual muddling. But, it’s a credit to the singers’ alertness and rapport that, especially in Acts 3 and 4, the drama was so engaging, for they seemed to have been largely left to their own devices. Allen’s only ‘intervention’, as far as I could see, is the introduction of several ‘babes-in-arms’ - or, in the case of the Countess, a babe-in-a-crib which is whipped away by a nursemaid (is that why she’s ‘off-limits’ for the Count at this time, leading to his extra-marital forays?). Among the chorus who serenade the Countess and celebrate the weddings, there are several young girls whose arms are encumbered by a swaddled child: a reminder of the welcome responsibilities of married life, or a warning perhaps that romance ends with wedlock? Certainly, the risks of indulging one’s passions are evident, as Marcellina palpitates on the bed during ‘La vendetta’ - Bartolo’s wish for revenge firing her own desire for Figaro - and the Countess almost expires from an overdose of sensual craving aroused by Cherubino’s serenading.

During the performance there was much excellent singing to admire, but I had misgivings as proceedings got underway as conductor Michael Rosewell (Director of Opera at the RCM Opera Studio) seemed determined to make a dramatic impact at the expense of idiomatic style. The overture was fast and unremittingly loud, but where was the elegance and wit of phrasing, the grace of line, the carefully delineated contrasts of colour and timbre? Accents were hammered home and the relentless tempo and temperature adversely affected the ensemble and intonation. There was little sense that the structure of the overture might articulate its own, and the opera’s, drama; impact was favoured over inference. Fortunately, though the pit was very ‘present’ throughout the performance, things settled down, the woodwind and horn tuning improved, and there was some pleasing playing as the evening progressed.

Adam Maxey has a handsome baritone, a relaxed manner, and - being of imposing height - a strong stage presence, but he needed to use greater variety of colour and dynamic to define Figaro’s character and his response to the unfolding drama more precisely. As Susanna, Julieth Lozano stole the show. Her soprano has a juicy middle range and there were flashes of real brightness at the top; she controlled the vocal line as skilfully as she commanded events. Indeed, this was not a Susanna to be messed with, as Conall O’Neill’s disconcerted Antonio discovered when she ripped his potted geranium to shreds when he frustrated her plans and wishes. But, Susanna’s charm was equally apparent and ‘Deh vieni, non tardar’ was beautifully sung.

I first enjoyed Sarah-Jane Brandon’s singing in 2010 when she performed with Mark Morris’s Dance Group in Handel’s L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato at the London Coliseum, and since then she’s been a frequent and rewarding presence on London’s concert and opera stages. She seemed out of sorts, though, in ‘Porgi, amor’ which, while controlled and firm of tone, lacked Brandon’s usual sensitivity of phrasing and colour. That she was unwell was confirmed when the cause for the extended interval was revealed by an announcement that Brandon would be replaced in Acts 3 and 4 by Josephine Goddard (the Countess in the alternative cast). Goddard demonstrated impressive variety of tone and the poignancy of ‘Dove sono’ was enhanced by some lovely pianissimo nuances.

Harry Thatcher was a convincing Count, complex, angry, frustrated and repentant. He was no fool, but he was outwitted, and his growing irritation and confusion was skilfully delineated by Thatcher in Act 3, culminating in a fiery but stylish ‘Vedro mentr’io sospiro’. This was a thoughtful characterisation, one which encouraged us to both condemn and understand, and ‘Contessa perdano’ was touching. Thatcher’s elegant bearing and urbanity were tempered with genuine human feeling, and we were inclined to forgive this Count for his frailties.

Lauren Joyanne Morris has a full, rich mezzo but she didn’t entirely persuade me in the role of Cherubino. A little too tall to be gamine, Morris did not seem to have determined precisely how to convey the page’s adolescent yearning - perhaps a little more direction would have helped. She sang strongly, but I’d have preferred a lighter approach, particularly in ‘Non so più’ which needs to sound both youthfully innocent and slightly breathless with a passion barely understood. Poppy Shotts was excellent as Barbarina, and her Act 4 aria ‘L’ho perduta, me meschina’ was confident and poised.

The comic trio entered into the Christmas-panto spirit, though the young singers inevitably found it a challenge to really convince as aged intriguers. Katy Thomson defined Marcellina strongly, though occasionally over-did the Hyacinth Bucket caricature. Timothy Edlin was terrific as Bartolo, relishing ‘La vendetta’ - and he was more dramatically persuasive when he removed his tricorn hat and we could see Bartolo’s bald pate and stringy curls. Joel Williams, as Basilio, completed the fine cast.

This was a long but enjoyable performance. The cast worked incredibly hard, to good effect, and the drama grew in charm and shine as the evening progressed. Tradition proved a real treat.

Claire Seymour

Mozart: The Marriage of Figaro

Count Almaviva - Harry Thatcher, Countess Rosina - Sarah-Jane Brandon/Josephine Goddard, Susanna - Julieth Lozano, Figaro - Adam Maxey, Cherubino - Lauren Joyanne Morris, Marcellina - Katy Thomson, Bartolo - Timothy Edlin, Basilio - Joel Williams, Don Curzio - Samuel Jenkins, Barbarina - Poppy Shotts, Antonio - Conall O’Neill, Bridesmaid 1/Chorus - Camilla Harris, Bridesmaid 2/Chorus - Jessica Cale; Director - Sir Thomas Allen, Conductor - Michael Rosewell, Designer - Lottie Higlett, Lighting Designer - Rory Beaton, Choreographer - Kate Flatt, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal College of Music Opera Studio.

The Britten Theatre, Royal College of Music, London; Monday 26th November 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/RCM%20Figaro%20image.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Marriage of Figaro: Royal College of Music, Britten Theatre product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=November 27, 2018

Unknown, Remembered: in conversation with Shiva Feshareki

The answer is Unknown, Remembered: a site-specific production which interweaves diverse materials, memories, media and meanings, and which will be presented at this year’s Spitalfields Music Festival , between 4th and 9th December. I met with composer Shiva Feshareki - who has composed a new work setting lyrics by Joy Division which, as Unknown, Remembered unfolds, will interact with Haroon Mirza’s 2010 film The Last Tape and Handel’s musico-dramatic characterisation of his tragic, desolate heroine - to discuss the ways in which these varied forms of expression come together to articulate a complex, multi-faceted, three-dimensional narrative which charts a journey from trauma to euphoria.

Shiva begins by explaining the genesis of her own contribution to Unknown, Remembered. Spitalfields Music Festival’s Artistic Curator André de Ridder was keen to centre a new work around the rock band Joy Division, formed in the 1970s and fronted by singer Ian Curtis. Shiva began exploring the lyrics of the band’s debut album, Unknown Pleasures (1979), thinking about ways of restructuring the narrative and finding a way of assimilating and communicating the voice of Deborah Curtis - the wife of Ian who took his own life in May 1980 aged just 23-years-old.

The desire to present a female perspective and voice, which might counter, engage with, reflect upon and assimilate the perspective of the male poet-narrator of these songs, was clearly central to Shiva’s artistic aims. But there is no ‘literal character’ in this work - which will be performed by soprano Katherine Manley, accompanied by viola da gamba, piano and live electronics; rather there is an accumulation of sung sentences that gradually coalesce to form a visceral echo-chamber of memory, experience and mediation. Shiva explains that she selected ten sentences from Curtis’s lyrics which during her 30-minute composition are presented in different orderings, arranged so that there is always ‘sense’ but that this ‘sense’ evolves as the permutations unfold. The use of live electronics, which create a ‘delay’ resonance, further complicates issues of time, place, meaning.

There is no defined ‘starting-point’ and preconceived ‘destination’; rather there are words which infuse, cohere and conflict to create what Shiva describes as a ‘sonic sculpture’. Linearity is rejected in favour of an aesthetic based upon accumulation, engagement and interaction. I ask Shiva whether there is any aleatoric dimension to the performance, and she explains that the use of live electronics does mean that there is an element of chance, but that it is fairly small. The chosen ten sentences have been carefully selected and arranged, though it is the physicality of the sound rather than its intellectual conception which is clearly at the forefront of Shiva’s aesthetic. Sound and movement, sound and space, the geometry of musical sound, the psychology of this geometry: these are her preoccupations and expressive aims and stimuli.

I ask Shiva about her approach to text-setting and, in keeping with the above described aesthetic, she speaks of the vocal line as being a spatial concept - a sculptured musical text - in which repetitions, silences and spaces between words define meaning. At the start of her composition the sentences are longer and more fluid; subsequently, there is more animation, shorter textual units, increased velocity.

Shiva Feshareki. Photo credit: Rupert Earl.

Shiva Feshareki. Photo credit: Rupert Earl.

I suggest that, while Shiva feels her conception of ‘sculptured sound’ is something new, one witnesses such ‘sound-worlds’ - the communication of lives, minds and hearts that are defined by the sonic architecture of voiced experience - in music from Monteverdi to the composers of the modern-day. I mention Richard Strauss’s early operas, Salome and Elektra, Schonberg’s Erwartung, as well as the work of Stockhausen and others who developed concepts of spatialization, not only in electronic music: after all, Stockhausen called for new kinds of concert halls to be built, ‘suited to the requirements of spatial music’. Shiva agrees that Stockhausen’s aesthetic is relevant to her own work; but she seeks a simpler, more ‘stripped back’ form of expression, one which communicates more directly. And, she explains that the music of James Tenney - in particular his conception of the psychology of sound, and his use of text - has exerted a stronger influence on her own work.

We come back to the varied components which will contribute to the audience’s experience of Unknown, Remembered. Haroon Mirza’s The Last Tape was first presented in VIVID’s garage space in Birmingham’s industrial Eastside district in 2010, and comprises film and sculpture, bringing sound and light together to form a literal and metaphorical electric current which is kinetic and immersive. An actor-musician, Richard ‘Kid’ Strange, reinterprets Beckett’s last play - in which the protagonist, Krapp, looks back at the events of his life as recorded onto tape - using previously unrecorded lyrics written by Ian Curtis; Mirza’s film presents Strange enacting the lyrics onto magnetic tape as the actor engages with audible sounds created by accompanying sculptures. The latter include furniture, radio and an LCD screen, as well as turntables which Shiva herself will manipulate, in an improvised fashion, during the video.

Unknown, Remembered is described by the Spitalfields Festival as being ‘site-specific’ although Shiva explains that while the relationship between sound and movement is always ‘specific’ to a performance venue, this aspect is not the starting-point for the projected evening performance. It’s important to create a work that is fluid; that can sustain and develop a ‘life’ as it moves through time and across space. Each repetition of Haroon’s installation involves an exploration of context and fresh experimentation and interaction.

And, then, there’s Handel, whose dramatic soliloquy will also part of the aesthetic mix. Emotions such as love and anger, betrayal and anger, seem to hover over the diverse components. But, if I’m honest, I’m both bewildered and fascinated as to how the parts might form a ‘whole’. I guess I will have to let go of concepts such as coherence and submit to immediacy and interaction, dialogue and dialectic, though Shiva - who leaves me to head to the first staged rehearsal of Unknown, Remembered - is still herself to see how the various parts might speak to each other and embody sonically and spatially expressive architectural forms. She speaks too of her appreciation of the unusually broad expanse of time that has been available to develop, create and rehearse Unknown, Remembered.

For those who want a foretaste and further explication, there’s an insight event at 4.15pm at Chapel Royal of St. Peter Ad Vincula, HM Tower of London at which at which Handel’s La Lucrezia will be performed, and when André de Ridder, director Marco Štorman and Shiva Feshareki will host a Q&A session. Otherwise, you’ll have to wait for my cogitations after the performance on Sunday 9th December.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Shiva%2040%20by%20Igor%20Shiva.jpeg%20%281%29.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Unknown, Remembered, Spitalfields Music Festival 2018

product_by=A preview by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Shiva Feshareki

Photo credit: Igor Shiva

November 25, 2018

Old Bones: Iestyn Davies and members of the Aurora Orchestra 'unwrap' Time at Kings Place

Muhly’s Old Bones adopts an idiosyncratic angle from which to reflect upon ‘Time’. Heard here in a new arrangement, conducted by the composer, for harp, celeste and string quartet, the text (by Richard Buckley, Philippa Langley and Guto’r Glyn) narrates the discovery and exhumation of the bones of Richard III in a car park in Leicester in 2012. A fragmented texture suffused with the cello’s pizzicato energy conjures the excitement of detection and revelation - “They dug in that spot, and the leg bones were revealed”. Davies’ composure and narrative focus drew us into the significance of the unearthing, and we soon became as compelled as the onlookers whose transfixed gaze is suggested by the harp’s oscillations and the repetitions of the viola’s melody. The fusion of past and present is embodied in the text itself, with third-person narration from the perspective of the present juxtaposed with first-person observation and reflection from the medieval past. The participant’s resonant announcement, “King Henry won the day”, was celebrated by the assertive lower strings, while the strange, disturbing feelings experienced by the modern-day ‘archaeologist’, “I am standing on Richard’s grave”, were evoked by churning, twisting harmonies. Slowly rising from a sustained pianissimo pause, the dead King himself seemed to reclaim life, “Now you can understand me”, “I’m ready”, the clarity and strength of Davies’ vocal exclamation suggesting the ghostly compulsion to speak from the grave as well as the madness of the modern-day observer: “Everyone else was looking at old bones, and I was seeing the man.”

Muhly’s Clear Music for cello, harp and celeste also unites present and past, being thematically based upon an early choral work by John Taverner, Mater Christi Sanctissima. Unfolding an eloquent opening melody, cellist Sébastien van Kuikj fell from a beautiful high-lying opening to richer, heavier grains of the lower strings, while the entry of the harp and celeste conjured the luminous spaciousness of Renaissance choral polyphony and the towering cathedrals that such music evokes in musical form. Motion for clarinet, piano and quartet similarly builds upon a Renaissance fragment, from Orlando Gibbons’ verse anthem See, see the Word, and the instrumentalists ranged with a rapidly accelerating sweep through vivid terrain.

Interweaved between old and new were instrumental works from the late-nineteenth century. Pianist John Reid opening the concert with the quietly breathing pulse of Satie’s Third Gymnopédie while harpist Sally Price conjured first heavenly light and air, and then ripples of colour, in Debussy’s Danse Sacrée et Danse Profane. Against the sensitive nuance of the piano accompaniment and the low silkiness of Hélèle Clément’s viola obbligato, Davies worked hard to communicate the yearning and fulfilment of Brahms’ Gestillte Sehnsucht (Assuaged Longing) but while there was firm resoluteness and a relaxed power the countertenor struggled to convey the Straussian passion which infuses this lied.

Two works by Thomas Adès made the strongest impression. Written when the composer was just eighteen-years-old, The Lover in Winter (1989) is a delicate miniature song-cycle whose Latin texts speak of the warmth with which love can assuage and transform the cold, bleak season. At the start, the strangeness and menace of this winter world is evoked by the unsettling intervals of the voice’s descending scale, ‘Iam nocetteneris’ (Now the cold harms what is tender). Here, Davies’ pure sound was a shining ray of wintry sunlight, while in the third song, ‘Modo figescit quidquid est’ (Soon all that exists grows cold), a beautiful, blanched tone captured the frozen immobility of the landscape, cracking icicles sparkling in the piano accompaniment. The fire of the lover’s kisses surged through the wavering vocal line at the opening of the final song, ‘Nutritur ignis osculo’, while the fragmentation of text and melody at the close conveyed a quasi-transcendental force: ‘nec est in toto seculo plus numinis’ (there is not in all our age more of the holy power).

Adès’ mysterious Four Quarters (2010) was brilliantly played by the four string players from the Aurora Orchestra. At the start, ‘Nightfalls’ opened up vast vistas of time and space, as high and low lines wove an ethereal web. The rhythmic displacements of ‘Morning Dew’ were skilfully controlled, accents pointedly placed, while in ‘Days’ the instrumental voices piled upon one another creating thick textures and tones of lovely colour, underpinned by the shapely cello phrases. The wildest wanderings conjured by the fiendishly complex 25/16 time-signature of ‘The Twenty-fifth Hour’, representing time spilling beyond the clock, did not ruffle the composure established by Alex Wood’s serene harmonics at the start, against the viola’s brushed chords and the cello’s gentle pizzicato.

Adès’ cycle evokes a tradition of English song stretching back to the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and the recital fittingly closed with Muhly’s arrangement - for an ensemble comprising all the present musicians - of John Dowland’s beautiful lute song, Time Stands Still. Now, Davies’ voice seemed somehow ‘released’, more freely expressive than previously, hovering above and then nestling gently into the muted strings’ cadential consonances. Viola and cello echoed and intertwined with the vocal phrases, while the contrasting harp colour seemed to embody the innate rhetoric and inner debate of the lyrics: ‘If bloudlesse envie say, dutie hath no desert,/Dutie replies that envie knows her selfe his faithfull heart.’

The text of Dowland’s song, which was published in 1603, is laden with emblems which suggest that the lyrics are a panegyric to Queen Elizabeth I - fittingly so, for, looking ahead, if at Kings Place Time will shortly come to a point of rest and silence, then Venus is soon to be awoken and given voice.

Claire Seymour

Iestyn Davies (countertenor), Sally Pryce (harp), John Reid (piano/celeste), Principal Players of Aurora Orchestra

Satie - Gymnopédie No.3; Thomas Adès -The Lover in Winter; Nico Muhly - Clear Music; Debussy -Danse Sacrée et Danse profane; Brahms - Gestillte Sehnsucht; Muhly - Old Bones (world premiere of new arrangement), Motion; Adès - The Four Quarters; Dowland (arr. Muhly) Time Stands Still

Kings Place, London; Friday 23th November 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/iestyndavies-40-Chris-Sorensen.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Old Bones: Iestyn Davies and members of the Aurora Orchestra at Kings Place product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Iestyn Davies (countertenor)Photo credit: Chris Sorensen

November 24, 2018

Cinderella goes to the panto: WNO in Southampton

The single ‘comic’ opera alongside the nine serious works that he wrote for the Teatro San Carlo in Naples between 1815 and 1822, it was regarded by the French poet Théophile Gautier as “a bottomless treasure, as if someone, in a fit of extravagance, plunged their arms up to their elbows into a pile of precious stones and then randomly started to throw handfuls of rubies and diamonds up into the air”. However, others lamented Rossini’s subversion of sentimental comic convention. Stendhal, after attending performances in Milan and, two years late, in Rome, expressed his dissatisfaction: “performance after performance left me cold and unmoved, beautiful as it is, [the music] seems to me to be lacking in some essential quality of ideal beauty.”

Above all, Stendhal lamented what he felt was the absence of ‘true’, elevating emotion in the portrayal of the characters of humble origin. Jacopo Ferretti’s libretto places the well-known fairy tale in a bourgeois context. Out with the fairy godmother and in with a charitable philosopher-cum-tutor who wishes to see his princely charge marry a ‘good’, honest lass. Out with the cruel step-mother and in with a socially and financially grasping step-father, Don Magnifico. Out with the glass slipper and in with a glittery bangle, a simple gift from the disguised Prince Ramiro which confirms Cinders’ lack of snootiness and avarice. Stendhal complained that Rossini’s score illuminated nothing but “the petty hurts and pettier triumphs of snobbishness”.

Giorgio Caoduro (Dandini), Fabio Macchioni (Don Magnifico). Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Giorgio Caoduro (Dandini), Fabio Macchioni (Don Magnifico). Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Director Joan Font’s production - first performed by Welsh National Opera in 2007 - tries to resurrect some of the transformative magic of Alice’s Wonderland … by making a trip to Poundland. Designer Joan Guillén’s sets and costumes are bold and brassy: all plastic and plasticine and primary hues. Font and his Barcelona-based company Comediants have often exploited Mediterranean carnivalesque, and one might wonder if Font’s conception was influenced by Gautier’s praise: “Looking again at the music one sees how, just like playing the castanets, a sparkling line of trills and arpeggios blossoms forth. The music sings and laughs!” For, Font conjures the eighteenth-century Enlightenment through the vitality of a Spanish palette and the hyperbole of cartoon caricature.

Heather Lowe (Tisbe), Aoife Miskelly (Clorinda). Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Heather Lowe (Tisbe), Aoife Miskelly (Clorinda). Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

The mundane, magical and plain mischievous co-exist. Cinders goes to the ball in a sedan chair which her rodent ‘courtiers’ and carpenters have assembled from a shabby chest of drawers; the Prince’s coach is magicked into being by some rotating mirrors … but later its miniature model is derailed by a roguish rat. Font puts the panto back into a period piece which had itself embodied the tension between ‘pure’ sentimentality and sensibility as hijacked by middle-class social climbers, but in so doing takes away much of the genuine enchantment of Rossini’s music as visual gags overpower vocal expression.

To some extent, though, this production was defeated by the size of Southampton’s Mayflower Theatre; when it opened in 1928 it was the largest theatre in the south of England, and still seats almost 2,300. Guillén’s designs seem to carry the cast to the far reaches of the vast stage; when atop the raised balcony at the rear, descending the framing stairs, or nestled within the grey-brick inglenook - especially when the mantle was raised to reveal the grand entrance to the Prince’s palace - the soloists sometimes struggled to project.

Likewise, in this barn of an auditorium conductor Tomáš Hanus struggled at times to keep the ensemble forces together. Proceedings got underway with a somewhat sluggish, desultory overture, with some questionable tuning from horns and wind, and rather listless Rossinian crescendos which were aching for an injection of ‘Formula-1’ acceleration. The patter of Don Magnifico’s first aria - sung briskly and ebulliently by Matteo Macchioni - in which he curses his daughters for waking him from his dream of being turned into a donkey - left the WNO Orchestra trailing in his wake. But, subsequently, Hanus put his foot on the pedal and left the Prince’s courtiers lagging behind. The ensembles were often metrically messy and occasionally in danger of skidding of the circuit. Perhaps it did not help that the laughs came from the visual trappings rather than from the dramatic interaction of the cast who were often left languishing in theatrical isolation in the ensemble numbers.

Matteo Macchioni (Don Ramiro), Tara Erraught (Angelina) Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Matteo Macchioni (Don Ramiro), Tara Erraught (Angelina) Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

That said, some superb singing offered much to admire. Don Magnifico might come across as a mean-spirited materialist but Fabio Capitanucci gave him a patina, at least, of lovability - and demonstrated a fine technique and good dramatic judgement. As Clorinde and Tisbe, Aoife Miskelly and Heather Low established their respective characters well at the start - much poncing, preening and ‘prettifying’ - and despite the parody which infects their song, and the brittleness of their boasting and bullying, they never sounded shrill.

As the human philosopher, Alidoro, Wojtek Gierlach - denied a magic wand but cloaked in a star-spangled cape - was a sonorous Prospero-cum-Sarastro, and if he didn’t quite attain a spiritual stature then he sang with beauty and authority.

Prince Ramiro was neatly sung by Matteo Macchioni; his tenor has brightness if not real bloom, and he presented a charming characterisation of a man who is more an emblem than an embodiment of royalty, and who doesn’t really find his ‘self’ until he’s wearing someone else’s suit.

Tara Erraught (Angelina), WNO Dancers. Photo credit: Jane Hbson.

Tara Erraught (Angelina), WNO Dancers. Photo credit: Jane Hbson.

Wearing the figurative crown though, appropriately, was Tara Erraught, who somehow imbued Cinderella’s lovely first aria, ‘Una volta c’era un re’, with sadness, longing, and hope, simultaneously. She was both of this world - down-to-earth and without illusion - and innocently unworldly. Vocally, her line was pure and controlled; the coloratura clean and clear; the pristine, polished evenness and sparkle of her tone heart-winning. No wonder the Prince was smitten. A pragmatist rather than a Prince hunter, this Cinders did not let good fortune tarnish her innocence or dull her natural glow of goodness.

Cinders’ helpmate-rodents - ever-present, ever-twitching - both stole the show and kept it on the road: observing and facilitating, overseeing and fixing. But, when the loudest applause is generated by the balletic unrolling of the red carpet by a pair of rats, something must surely be amiss. But if, like Stendhal, one missed a certain nobility of feeling, then at least, and luckily for the rats, there was no Cheshire Cat lurking in the inglenook.

Claire Seymour

Rossini: La Cenerentola (co-production between Welsh National Opera, Houston Grand Opera, Gran Teatre del Liceu and Grand Théâtre de Genève)

Angelina (Cinderella) - Tara Erraught, Clorinda - Aoife Miskelly, Tisbe - Heather Lowe, Don Ramiro - Matteo Macchioni, Don Magnifico - Fabio Capitanucci, Alidoro - Wojtek Gierlach, Dandini - Giorgio Caoduro, Rats/Dancers - Colm Seery, Darío Sanz Yagüe, Ashley Bain, Meri Bonet, Lucy Burns, María Comes Sampedro, Lauren Wilson; Director - Joan Font, Conductor - Tomáš Hanus, Revival Director/Choreographer - Xevi Dorca, Designer - Joan Guillén, Lighting Designer - Albert Faura (realised on tour by Paul Woodfield), Welsh National Opera Orchestra.

Mayflower Theatre, Southampton; Thursday 22nd November 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/WNO%20La%20Cenerentola%20Cast%20of%20La%20Cenerentola%20Photo%20credit%20%C2%A9%20Jane%20Hobson.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Welsh National Opera’s La Cenerentola, at the Mayflower Theatre, Southampton product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Cast of WNO La CenerentolaPhoto credit: Jane Hobson

November 23, 2018

It's a Wonderful Life in San Francisco

Maybe you’ve seen the 1946 film It's a Wonderful Life. It seems many of you have, maybe most of you, and it seems that Jake Heggie and San Francisco Opera know you are yearning to return to that simpler time when the housing crisis was easily solved by simple community economics, big government was no where to be seen or felt, and winged Christian angels, like the one once atop your Christmas tree, watched over you. And, well (there can be no doubt), you are Christians and that prayers actually worked.

Though you once might have dreamt about college and a larger world, the world of Bedford Falls, NY is already pretty big in itself, or big enough to satisfy the ambitions of a good husband and father and citizen. When an outside evil intrudes (the “yellow peril”) you hold a spine-chilling rally to "Make America Great" again.

Set design by Robert Brill, costume design by David C. Woolard

Set design by Robert Brill, costume design by David C. Woolard

Mr. Heggie and Mr. Scheer’s It’s a Wonderful Life is a tight (it enjoyed a gestation period in Bloomington and Houston before arriving at the War Memorial), beautifully crafted opera that tells its story in high operatic terms — it is a string of lyric moments woven into compelling, if trivial episodes that propel us to a final crisis that even the opera’s hero, George Bailey of Bedford Falls, NY learns is trivial — that it’s not worth killing yourself over $8000 ($111,000 in today’s dollars).

Mr. Scheer proved himself a brilliant librettist in his masterful adaptation of the Great American Novel Moby Dick for composer Heggie. Jake Heggie himself now has resolutely proven himself the Great American Composer with It’s a Wonderful Life, following Moby Dick and Dead Man Walking, works that embody the American spirit in flowing, intensely lyrical, American middle high-art musical terms. In It’s a Wonderful Life Mr. Heggie exploits the richness of American vaudeville, and dwells incessantly on the mannerisms of the American musical as well. Startlingly the opera begins with an ear-splitting imitation of the primitive sound of postwar movie theater amplification.

The opera’s coup de théatre is the moment George Bailey understands that if he had never existed there would be no music. It becomes a spooky, spoken world that makes us encourage George to quickly get back to the world of everyday problems that you can easily sing about — eschewing, of course, any whiff of the psycho-sexual violence that is the meat of real opera.

But wait. There was a second coup de théâtre and that was an urge to sing "Auld Lang Sang" that gripped us all when George at last hugged his wife and kids standing before a brilliantly lighted Christmas tree under the loving gaze of his suspended Guardian Angel. Well, we all belted it out with the maestro before leaping to our feet to salute the very fine artists and the excellent production.

Orchestrally It’s a Wonderful Life is scored for single winds (except two horns) and strings making it easily accessible for smaller holiday productions in regional theaters. On the other hand there can be no doubt that It’s a Wonderful Life will find international success in theaters throughout the world as a throbbing example of Americana.

Though of great sophistication the production by Leonard Foglia and Robert Brill was quite simple — a unit set of countless, identical floating panels that were doors, maybe tombs, other times wallpapered panels, floors, clouds that were heaven, streets, etc. The angels in heaven were breathtakingly flown in from the celestial spheres of the War Memorial fly loft. Costuming was the period of the film (1946).

There was considerable choreography, some maybe expertly fronted by dancers of the San Francisco Opera Ballet, but mostly executed by the principals together with 28 members of the San Francisco Opera Chorus, presumably chosen for their lithe bodies to fit the costumes of students of Bedford Falls High School and then the not-too-well-fed Irish and Italian immigrants that lived on the other side of the tracks.

Andriana Chuchman as Mary Hatch, William Burden as George Bailey, Keith Jameson as Uncle Billy Bailey

Andriana Chuchman as Mary Hatch, William Burden as George Bailey, Keith Jameson as Uncle Billy Bailey

The casting for the production made its bow to multi-culturalism by casting George Bailey’s guardian angel Clara [as in The Nutcracker] with the South African soprano Golda Schultz who set the standard for the high-level vocal performances that characterized the evening. American baritone William Burden successfully embodied the young George Bailey to then become the distraught middle aged banker and the loving husband. Canadian soprano Andriana Chuchman brought force and beauty of voice to create George’s emotional anchor, his wife Mary Hatch (who did escape to New York but came right back to Bedford Falls to create a home for George).

Confined to a wheelchair as the crooked businessman Mr. Potter, Los Angeles bass-baritone Rod Gilfry exuded greed and selfishness, his wheelchair coldly and calculatedly guided by the production’s one supernumerary. George’s brother Harry who does go off to college was sung by Canadian baritone Joshua Hopkins with vibrant presence. Genuinely batty Uncle Billy was aptly played by Keith Jameson, and George’s mother found big prominence as sung by San Francisco mezzo soprano Catherine Cook.

There are 34 named roles in It’s a Wonderful Life. Of the principals identified above Mr. Burden, Mr. Gilfry and Mr. Hopkins survive from the Houston cast. Conductor Patrick Summers from the Houston Opera ably helped the singers carve out their roles, evoking suitable orchestral pizazz.

Disclaimer: I have not seen the Frank Capra film, It’s a Wonderful Life.

Wise opera goers could pay $10 for standing room for the brief 2 1/2 hours that fly by fairly quickly, though you may wish to suggest a few economies to Mr. Heggie.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Clara: Golda Schultz; Angels First Class: Sarah Cambidge, Ashley Dixon, Amitai Pati, Christian Pursell; George Bailey: William Burden; Harry Bailey; Joshua Hopkins; Uncle Billy Bailey: Keith Jameson; Mother Bailey: Catherine Cook; Mary Hatch: Andriana Chuchman; Mr. Potter: Rod Gilfry; Helen Bailey: Carole Schaffer. Chorus and Orchestra of the San Francisco Opera. Conductor: Patrick Summers; Stage Director: Leonard Foglia; Set Designer: Robert Brill; Costume Designer: David C. Woolard; Lighting Designer: Brian Nason; Projection Designer: Elaine j. McCarthy; Choreographer: Keturah Stickann. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, November 20, 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/WonderfulLife_SF1.png

product=yes

product_title=It’s a Wonderful Life in San Francisco

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Golda Schultz as Clara [All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

Des Moines: Glory, Glory Hallelujah

Scheduled in the wake of Veteran’s Day celebrations, and performed at Camp Dodge, the work had an especial, gut-wrenching resonance as it tells the true story of

an American family torn apart during the unsettling era of the unpopular Vietnam War. Cipullo’s masterfully taut adaption of Tom Philpott’s book of the same name, makes a cogent impression in just seventy-five compact minutes with a score that is by turns chaotic, angular, melodic, harmonious, and even at times, serene.

This chamber opera utilizes just four characters, or really just two. I will explain. As the American soldier held longest in captivity during that prolonged conflict, Colonel Jim Thompson suffered unimaginable hardship in the jungles of Southeast Asia. His wife Alyce suffered with her own daunting challenges back home, raising four children and facing brutal, heartrending choices.

The story largely concerns their complicated relationship, as each must contend with personal struggles arising from Thompson’s disappearance, liberation, repatriation, and it is revealed, abandonment by his spouse. The opera utilizes a brilliant device of having a second couple, a “younger” Jim and Alyce reflecting, challenging, and informing their “older” selves. By seeing where the couple began, we see how they arrived at their current state of affairs.

The four actors interact freely and seemingly spontaneously, sometimes in a certain reality of the moment, and on other occasions, time traveling to speak with and about their alternate incarnations. They sometimes briefly enact other characters. This is not a strictly linear narrative but rather an intriguing mosaic of impressions and factual information, stunningly interwoven in a soul stirring evening of profound suffering and eventual forgiveness and redemption. Jim Thompson is truly a heroic subject, worthy of ennoblement by a thrillingly varied score, mesmerizing libretto, and a flawless, kaleidoscopic staging by the abundantly gifted director, Kristine McIntyre.

The central playing space has audience members on all four sides and Ms. McIntyre has devised fluid, continuously morphing stage pictures that not only underscore the dramatic truth of the situations, but also keep each segment of the audience fully immersed in the drama by having at least one character playing in their direction. She drew deeply personal portrayals from her superb cast. And she has obviously toiled to great effect as she developed “younger” and “older” versions of Jim and Alyce that share identical personality cores as well as an eerily unified approach to the roles’ physicalization. We really believed that these were two embodiments of the same two souls.

I may have said it before, but it bears repeating: Kristine McIntyre is one of the foremost directors working in opera today. If you see her name in the credits, rest assured it is going to a top tier, often revelatory experience. She was ably abetted by a superlative creative team.

Adam Crinson’s effective set design features a simple island, an “X” of platforms, with flats masking entrances on all four corners, which are painted in shades of tropical green, marked with images of falling palm fronds that “spill” onto the stage. There is something almost sacrificial of the altar-like raised central platform. The simple, short bamboo stools and piles of (unread? unreceived?) letters guttered in the corners of the set are the only real dressing, save for the silver stars hanging from the grid that reinforce an important “beat” in the plot. Judicious use of well-produced film projections added immeasurably to the visual impression.

Photo credit: Duane Tinkey.

Photo credit: Duane Tinkey.

Kathy Maxwell has worked wonders with a beautifully calibrated lighting design, all the more remarkable for the economy of instruments and the difficulty of lighting an arena configuration. Ms. Maxwell devised a moody, expressionistic, characterful look that served the dramatic moment at every turn. Heather Lesieur’s deceptively simple costume design was a key factor in visually defining these characters, especially the eternally pregnant “younger” Alyce, and the well chosen black horn-rimmed glasses for both Alyce’s.

As Jim Thompson, baritone Michael Mayes anchored the evening with a star turn that was simply amazing. (Or is it, A-Mayes-ing?). There is no aspect of this tremendously complex role that eludes him musically or dramatically. His deep personal commitment to portraying this eminently tragic figure is exceeded only by his incredibly effective vocalizing. Having experienced his straightforward, powerfully sung Scarpia a few seasons ago, I was not prepared for the total mastery of the nuances he brought to bear on this evening.

Mr. Mayes not only gifted us with the powerful beauty of his burnished instrument, but he also made my jaw drop with meticulously calculated, wondrously controlled sotto voce effects, including some breath taking forays above the staff. His complete immersion into the suffering and physical disintegration of his character were as commendable as they were poignant. His tour de force impersonation was well matched by his “younger” counterpart.

John Riesen’s “Younger Thompson” held the stage with a vibrant, focused tenor, and an impassioned performance of complete commitment and coltish deportment. Mr. Reisen bolted about the stage, flailed at his captors’ abuse, repeatedly flung himself on the floor, and managed to do all of this while singing with secure abandon.

Photo credit: Duane Tinkey.

Photo credit: Duane Tinkey.

Kelly Kaduce was a magnificent Alyce, turning in yet another finely etched performance. The soprano was in especially fine voice, her secure, pliable tone and dramatic delivery in complete service to the role at hand. She is a beautiful woman, often presented in glam make-up and attire to luxurious effect. On this occasion, Kelly appeared against type, embodying a rather plain hometown girl. Her acting was simple, candid, and she totally believed in the correctness of her character’s choices. The horrible stillness encompassing her confessional aria was underscored by her alluring, purposeful delivery.

As “Younger Alyce,” Emma Grimsely showed off a silvery, gleaming soprano that was a perfect contrast to Ms. Kaduce’s weightier delivery. Ms. Grimsley was a wholly sympathetic figure, and her limpid, freely produced singing was enchantingly delivered. One caution: her subtle singing early on may have eluded the ears of a few audience members. One caveat to Mr. Cipullo: “Younger Alyce” is the only character who does not have an aria. Although she does have the radiant final phrase of the opera, might you please give her a solo “scena” to balance the quartet?

In the pit (here an elevated platform), Joshua Horsch conducted with steady acumen and considerable aplomb. Maestro Horsch has helmed this piece before and it shows in his well-controlled, colorful reading. The orchestration calls for substantial exposed playing from a small band of (for all intents) soloists, and the conductor drew a highly satisfying ensemble reading from his highly skilled instrumentalists. Horsch ably collaborated with his quartet of singers with a completely realized orchestral partnership.

There are many highlights in Tom Cipullo’s score that deserve mention: “Older Thompson” has a riveting litany of (mostly) shit happenings that occurred, unbeknownst to him owing to his isolation, that echo Billy Joel’s We Didn’t Start the Fire. The 23rd Psalm serves as a disturbing Cantus Firmus sung by “Younger Thompson,” as the other three characters embellish it with edgy, turbulent vocal lines. The orchestration includes many instances of telling effects, including the cruel interjections of a slapstick as the captive Jim is being abused.

Photo credit: Duane Tinkey.

Photo credit: Duane Tinkey.

Whether by luck or design, there was also a stunning impression created by the “younger” duo being shorter than their “older “ counterparts, conveying the impression that the weathered adults are looming over, dominating their remembered selves. This wholly successful presentation was complemented by a meaningful talk back after the show that included Vietnam vets and military personnel currently serving.

Des Moines Metro Opera is a major force in the national opera scene, and if any reinforcement of that was needed, after this remarkably effective mounting of Glory Denied, I can emphatically say: Mission Accomplished.

James Sohre

Glory Denied

Music by Tom Cipullo

Text by Tom Cipullo based on the book

By Tom Philpott

Older Thompson: Michael Mayes; Older Alyce: Kelly Kaduce; Younger Alyce: Emma Grimsley; Younger Thompson: John Riesen; Conductor: Joshua Horsch; Director: Kristine McIntyre; Set Design: Adam Crinson; Lighting Design: Kathy Maxwell; Costume Design: Heather Lesieur

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DSC_3106.png

image_description=

product=yes;

product_title=Des Moines Metro Opera: Glory Denied

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=

Photo credit: Duane Tinkey

November 22, 2018

In her beginning is her end: Welsh National Opera's La traviata in Southampton

McVicar seems to have taken a leaf out of T.S. Eliot’s book: ‘say that the end precedes the beginning,/ And the end and the beginning were always there/ Before the beginning and after the end.’ For, during the overture we gaze at designer Tanya McCallin’s shrouded room, its dark, pendulous drapes countered by frail white coverings, shadows the only inhabitants illuminated by lighting designer Jennifer Tipton (lighting realised on tour by Benjamin Naylor). A cloaked figure appears, pauses in melancholy reflection, then is carried by ponderous steps the length of the fore-stage, head bent, to the accompaniment of fragile strings, so light as to suggest a chamber-like intimacy which the visual scene denies.

Before we know it, the room has gone, swept aside by a falling front curtain and the cellos’ melodic gaiety (although on this occasion at Southampton’s Mayflower Theatre the section sang less as a gleeful coterie and more as individual revellers), as we swing back into the past and into the insalubrious fin-de-siècle salons of the French capital where the courtesans tease and tussle, frothing their skirts and spreading the legs, amongst the bustled and bow-tied bourgeoisie. Think John Singer Sargent meets Toulouse Lautrec.

The dining table and grand piano totter with sparkling glasses, piled plates and gustatory pleasures. It’s clear as they gather eagerly and sway to a buoyant lilt that during the brindisi the guests are truly enjoying themselves. But, they are literally walking on Violetta’s grave: the floor is a black-marble slab, etched with the dates that mark La traviata’s beginning and end. When Alfredo subsequently takes Violetta in his arms and tells her she must give up a life that will kill her the proleptic irony is disturbing.

Philip Lloyd Evans (Marquis d’Obginy), Rebecca Afonwy-Jones (Flora) and WNO Chorus. Photo credit: Betina Skovbro.

Philip Lloyd Evans (Marquis d’Obginy), Rebecca Afonwy-Jones (Flora) and WNO Chorus. Photo credit: Betina Skovbro.

If the choral crowd are sometimes a little static - though hearty of voice - then individuals are brought to the fore. James Cleverton’s resounding Baron Douphol watches the nascent courtship from the front of the stage isolated from the other carousers’ carnality and excess by his jealousy and anger. Sian Meinir’s Annina hovers watchfully; Flora’s indigo-blue frock gleams as richly as Rebecca Afonwy-Jones mezzo-soprano and as brightly as her smile.

Then, suddenly Violetta and Alfredo find themselves alone; the viewer is disorientated by the change of perspective, sucked into their intimacy. Kang Wang’s evening-dress looks a little on the large size but his voice is stylish and secure, if lacking in a really Italianate warmth and ring at the top. Anush Hovhannisyan is taking the role of Violetta in the two Southampton performances; her soprano perhaps does not have the fullness of tone and nuance of colour to really engage our sympathies but the Armenian soprano has undeniable theatrical presence, and she worked hard to communicate Violetta’s determination and courage, as well as to intimate her frailty - no easy task when vocally the singer in the role must be so robust and sparkling. Hovhannisyan may sometimes have only found a secure line upon the repetition of a vocal phrase, but she has a lovely way of withdrawing the note at the top to convey fragility and femininity - and who would begrudge her repetition of this winning gesture.

Kang Wang (Alfredo). Photo credit: Betina Skovbro.

Kang Wang (Alfredo). Photo credit: Betina Skovbro.

Act 2 finds Violetta prone on her bed, the stage divided by a the curving hoops of a half-lowered curtain revealing first the lovers’ bedroom, the shadows looming like ghosts, and then, with a balletic swish, the brightly lit, gracious ante-room in which Violetta awaits her visitors. If Act 2 is fired by a greater intensity and truly compelling dramatic momentum, then this is in no small part due to Roland Wood’s gripping Giorgio Germont. Wood’s baritone imposes itself with wonderfully supercilious smoothness and colour, matching the contemptuous condescension of his gestures - the lifting of frilled layer of Violetta’s dress with his cane, as he sneers about the extravagance of life is the apex of arrogance. Wood’s encounters first with Violetta and then with his son in this Act are both menacing and moving. His iron-rod back, as he refuses to take the open-hearted Violetta in his arms, as a daughter, is chilling.

Kang Wang (Alfredo) and Roland Wood (Giorgio Germont). Photo credit: Betina Skovbro.

Kang Wang (Alfredo) and Roland Wood (Giorgio Germont). Photo credit: Betina Skovbro.

Back in Paris, the excitement at Alfredo’s luck at cards is matched by the exuberance of the gypsy dancers’ displays; and the entertainment cleverly integrates the themes of class and money, as Philip Lloyd-Evans’ oily Marquis d’Obigny shoves some crumpled louis down the cleavage of one of the can-can girls, and a male ‘matador’ scrabbles on the floor for the revellers’ carelessly thrown loose notes. Later there is a terrible desperation and degradation when Alfredo (inelegant in out-sized suit) showers his gambling profits at the horrified over the salon marble, insulting and intimidating Violetta, who shrinks under his scornful, spiteful retort that he has now repaid his debts. Again, some of choral blocking is a little staid: when towards end of chorus, Flora ventures forward to comfort Violetta and is restrained by the Marquis, one wishes that McVicar had integrated more such telling details. Similarly at the close of the scene, the principals too are static, strung out along the front of stage - a little disengaging in their spatial isolation and stillness, with Pere Germont seated exhaustedly stage-right, Alfredo slumped on floor centre-stage, and Violetta standing, just, stage-left.

WNO Dancers and WNO Chorus. Photo credit: Betina Skovbro.

WNO Dancers and WNO Chorus. Photo credit: Betina Skovbro.

Hovhannisyan comes into her own in the last Act much of which she delivers while horizontal on bed or floor, but with dramatic magnetism and vocal focus, her opening agonises accompanied with beautifully shaped violin accompaniment. Violetta’s fervent grasping, with faux optimism, at the arm of Martin Lloyd’s pragmatic Grencil recalls the superficiality of her earlier merriments. Past and present are fusing: when, Germont arrives to embrace her as a daughter, Violetta’s cry, “It is too late!”, is visually reinforced by the terrible funereal darkness and erasure of colour and warmth - even the meagre fire is extinguished, as Violetta’s heart essays its final flickers.

Conductor James Southall had kept a tight rein on the Welsh National Opera Orchestra up until this point, taking care that in the Mayflower ‘barn’ they did not overwhelm the singers. But, now the rat-a-tat of trombones was a spine-curdling knock of Death. One could only hope that T.S. Eliot was right when he professed that ‘to make an end is to make a beginning./ The end is where we start from.’

Claire Seymour

Verdi: La Traviata

Violetta - Anush Hovhannisyan, Alfredo - Kang Wang, Germont - Roland Wood, Flora - Rebecca Afonwy-Jones, Baron Douphol - James Cleverton, Marquis d’Obigny - Philip Lloyd-Evans, Annina - Sian Meinir, Doctor Grenvil - Martin Lloyd, Gaston - Howard Kirk, The Messenger - George Newton-Fitzgerald, Flora’s Servant - Laurence Cole, Dancers/Actors (Colm Seery, Darío Sanz Yagüe, Ashley Bain, Mori Bonet, Lucy Burns, María Comes Sampredo, Lauren Wilson; Director - David McVicar (revival director - Sarah Crisp), Conductor - James Southall, Designer - Tanya McCallin, Lighting Designer - Jennifer Tipton (realised on tour by Benjamin Naylor), Choreographer - Andrew George, Chorus and Orchestra of English National Opera.

Mayflower Theatre, Southampton; Wednesday 21st November 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/La%20traviata%20Kang%20Wang%20Alfredo%20and%20Linda%20Richardson%20Violetta%20Photo%20credit%20Betina%20Skovbro.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Welsh National Opera’s La traviata, at the Mayflower Theatre, Southampton product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Kang Wang (Alfredo) and Linda Richardson (Violetta)Photo credit: Betina Skovbro

Hubert Parry – Father of Modern English Song – English Lyrics III

By extension this also serves to highlight Parry's unique role in British music history. Britain has strong literary traditions : composers like Purcell worked with playwrights like Dryden. British audiences were receptive to Handel because he wrote for the theatre. His oratorios, like Mendelssohn's, connected to the role of music in British religious culture. Hence the predilection for vocal music and for choral music in particular. British music is music for voice, either declaimed or sung. The situation isn't dissimilar to France or Italy where sacred music and opera dominated, and even in Germany and Austria, symphonic music in the modern sense didn't take root until the 18th century. So much for the myth of Das Land ohne Musik !

Because Parry's songs specifically address English art poetry, they mark a departure into new territory which would later be developed by composers like Vaughan Williams and others who sought out folk tradition and by by composers like Finzi, who addressed Tudor, Stuart and Restoration poetry. Notice Parry's term “English Lyrics”, focusing on English as a language. Parry's outlook was progressive, alert to contemporary European influences, which is no demerit, given the extremely high quality of 19th century Austro-German music. Effectively, he was the father of modern British music. Please read more here about Volume I in this series (settings of Shakespeare and 17th and 18th century poets) and about Volume II (where Parry sets poets of the 19th century, close to his own time, not unlike the way that Schubert, Schumann and others set Goethe and Heine.

My heart is like a singing bird dates from 1909, and was written for the soprano Agnes Hamilton Harty, (wife of the pianist Hamilton Harty). The lines fly and soar - like a songbird - and Sarah Fox's clear, lyrical singing does it justice. The text is Christina Rossetti's A Birthday. Extending the imagery, The Blackbird, If I might ride on puissant wing and A Moment of Farewell. The first is relatively straightforward but its very simplicity evokes the folk song adaptations that became popular in the Edwardian period. A Moment of Farewell, (to a poem by John Sturgis) however is more sophisticated with an elaborate, rolling piano line, (pianist Andrew West) evoking the “buoyant emotion” of a “bird flying far to the ocean”. With The Sound of Hidden Music, Parry is writing art song as fine as any German composer’s. The piano introduction flows elegantly, almost caressing Sarah Fox's lines. Although the poem, not specially adept, is by Julia Chatterton, unknown today, Parry's response lifts it well above the ordinary. The memory of “things of life that touch the heart are things we cannot see” warm the spirit in winter. It was signed on his 70th final birthday in 1918, inscribed with the words “Slowly and with deep feeling”. This was to be his last birthday, and final completed song. There is some evidence that he did not think he would live out the year, and indeed, he died some months later.

Just as Schubert set poems by people he knew, Parry chose poems by friends who meant a lot to him, which tells us much of his humane and caring personality. Nine of his seventy-four English Lyrics (eight included in this collection) are settings of John Sturgis, Parry's classmate at Eton and fellow student at Oxford. Like Parry himself, Sturgis was able to switch to art from business. Through the Ivory Gate describes a vision of a dead boyhood companion. “No friendship dies with death”, sings Roderick Williams, whose style of direct communication makes the song feel personal. A Stray Nymph of Dian, another Sturgis setting, describes a Grecian nymph, and draws from Parry a more declamatory approach. A Girl to her Glass is flirtatious, while Looking Backward is not melancholy - not a Parry characteristic - but thoughtful. Grapes is boisterous, as befits a paean to Bacchus. “Grapes, grapes, grapes beyond all measure!” sings Williams with good humour.

Alfred Perceval Graves, an Inspector of Schools, was well known in Victorian times. “I am weaving sweet violets, sweet white violets” sings Williams in A Lover's Garland. Parry's setting is elegant, reflecting the classical reference to “Heliodora's brow”. At the Hour the Long days Ends in lesser hands than Parry's might have veered close to parlour song, but he treats it with dignity. Graves's poem The Spirit of the Spring, with its references to Taunton town and archaic words like “maund” (a unit of weight) is quaint in an artificial way - he was no Housman or Hardy - but Parry, like Schubert, could elevate less than ideal verse with good musical setting.

The rather better poetry of Langdon Elwyn Mitchell inspired Parry to greater heights. Nightfall in Winter captures a sense of enveloping darkness. The piano plays single notes in succession, suggesting the steady coming of night, cold and frost. “The clouds obscure the sky with gloom”, sings Williams, his voice rising upwards for a moment before settling back into somnolent mood. Mitchell also wrote the text for From a City Window, one of Parry's best-known English lyrics. “I hear the feet below”, sings Sarah Fox, as West plays the bustling piano part, “(which) go on errands bitter or sweet whither I cannot know”. A long pause, for rumination before the second verse, “A bird troubles the night” evoking “vague memories of delight”. Another, shorter, pause before the final strophe “And the hurrying, restless feet below, on errands I cannot now, like a great tide ebb and flow”. A strikingly modern song, with its urban context and sense of unknown possibilities, the bird a symbol of longing yet disquiet. Although Parry's Twelve Sets of English Lyrics have been recorded before in various forms, this series from SOMM is a landmark because it presents the complete collection, together with good notes and good performances, establishing Parry's role as the pioneer of modern English song.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/SOMMCD272-cover-1024x1024.jpg

image_description=SOMMCD 272

product=yes

product_title=Sir Ch. Hubert Parry : Twelve sets of English Lyrics, Volume III

product_by=Sarah Fox, Roderick Williams, Andrew West, SOMM Recordings.

product_id=SOMM Recordings SOMMCD 272 [CD]

price=$18.99

product_url=https://amzn.to/2S4PU0j

Ravel’s Magical Glimpses into the World of Children

I loved vol. 4, whose main work was Ravel’s first opera, L’heure espagnole. Conductor Denève has, in the meantime, has become an ever-more-prominent figure on the world scene: during the 2019-20 season he will become music director of the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra, after some years as Chief Conductor of the Stuttgart orchestra heard here, as Music Director of the Brussels Philharmonic, and as Principal Guest Conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Denève has an interest in exploring new and forgotten repertoire: he recorded operas by Dukas and Prokofieff, as well as numerous works by Roussel.

The longer of the two works on this CD is the second of Ravel’s two operas (both of which are in a single act lasting less than an hour). Its title, impossible to translate, means something like “The Child and the Magical Things that Start to Happen to Him.” The opera consists of a series of very short scenes, in which a young boy, unnamed, refuses to do his schoolwork, taunts animals, breaks household objects, rips illustrated characters out of the wallpaper and his storybook, gets chastised by Mommy, then (I am interpreting a bit from this point on) falls asleep and dreams of the various objects, animals, and illustrated characters that he has mistreated in his waking life. They sing and dance and accuse, and he begins to understand. Finally, he binds (or dreams that he binds) the wounds of the squirrel that he has injured and calls out to his Mommy. Animals of the fields, concerned, take up his powerful cry, and the child, apparently now back from dreams, turns toward his mother and stretches out his arms.

The verses, written by the popular fiction-writer Colette, are inventive and full of subtle humor, mystery, and touches of violence—as well as much imitation of animal noises plus some pidgin English and Chinese. Ravel’s music is enchanting beyond description: a kaleidoscopic survey of musical styles, from sacred-choral to cheeky foxtrot and Piaf-like cabaret waltz (several years before Piaf began her career). L’enfant et les sortilèges is hard to stage, both for dramaturgical reasons and for musical ones—especially in a large hall, in which the frequent quick vocal patter and much of the orchestral tracery can get lost. But it is a delight to listen to on CD.

There have been numerous much-admired recordings: I join other critics in recommending the earliest one (1947, conducted by Ernest Bour) and the modern versions conducted by, most notably, Maazel, Previn, Jordan, and Rattle. (Ansermet’s recording, though somewhat uneven, also has splendid assets.) To these can now be added the fine rendering by Denève and the Stuttgart Orchestra, recorded in 2015. The vocal soloists are all native French-speakers, which helps enormously, especially when the text has to be spit out quickly (e.g., by the tenor who plays “The Little Old Man”: this character is the embodiment of the rules of arithmetic that the boy has refused to learn). They all sing with firm tone and with little or no wobble. The best-known of the singers, Annick Massis, has performed leading operatic roles (e.g., Lucia and Violetta) in major houses. In my aforementioned review of Denève’s vol. 4, I admired Paul Gay’s performance of the role of Don Iñigo Gomez.

The two participating choruses handle the French text beautifully. The innocent quality of the Karlsruhe Youth Chorus adds immeasurably to the final minutes of the work. The orchestral playing ravishes the ear.

Throughout the opera, the recorded quality is balanced and true, inviting you to listen attentively and rewarding you for doing so. The music flows with a natural lilt and lift. I wouldn’t want a single detail to be different, though some things are of course done differently on other recordings and are no less convincing there. (Late update: yet another first-rate recording of the opera has just been released, conducted by Mikko Franck: see the review here.)

The five “Mother Goose” pieces that complete the CD were recorded in the same hall (the Beethoven-Saal of Stuttgart’s Liederhalle) during a 2013 concert rather than under studio conditions. The sonics here, too, are remarkably detailed. The audience members are as quiet as church mice and, I suspect, deep in concentration—that’s how engaging the music-making is. They applaud vociferously at the end. A few quick wind passages are not perfectly rendered, but the advantages of a live performance here outweigh the small disadvantages, revealing how fine the SWR Orchestra is “in real time,” at least when led by the man who was their Chief Conductor for seven years (2005-12).

On the outside of the box, the title of this orchestral work is. astonishingly, mistranslated into German as Meine Mutter, die Gans , i.e., “My Mother, the Goose”! Fortunately, the English translation of the informative booklet essay is well handled, except that, in the cast list for the opera, it leaves Bergère untranslated. The word does not, here, mean a shepherdess (as some might assume) but a small upholstered armchair or loveseat. (As I said, furniture sings in this opera—long before a certain Disney movie.)

The booklet includes no libretto for the opera. An imaginatively updated singing translation in English is here.

How lucky the folks in St. Louis are going to be to have a conductor with such a fine sense of atmosphere, pacing, and color!

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book. image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ravel-Orch-Works-5.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Ravel: L’enfant et les sortilèges; Debussy: Ma Mère l’Oye (five pieces) product_by=Camille Poul (Child), Annick Massis (Fire, Princess, Nightingale), Maïlys de Villoutreys (Shepherdess, Bat, Owl), Marie Marall (Mother, Chinese Cup, Dragonfly), Julie Pasturaud (Small Upholstered Seat, Shepherd, Female Cat, Squirrel), François Piolino (English Teapot, Little Old Man, Tree-Frog), Marc Barrard (Grandfather Clock, Male Cat), Paul Gay (Large Wooden-Armed Chair, A Tree), Stuttgart Radio Orchestra, SWR Vocal Ensemble, Cantus Juvenum Karlsruhe, conducted by Stéphane Denève product_id=SWR Music 19033—62 minutes

About an enfant: Ravel’s Opera about Childhood and Debussy’s Prodigal Son

The only thing I minded were some inconsistencies of tuning in the opening two minutes and at the very end. The detailed sonics lack some of the mystery that Stéphane Denève brings out so well at various points in the studio recording of the work, reviewed here. But the clarity of detail also brings ample compensation. The music is conducted with keen stylistic awareness by Mikko Franck, music director of the French radio orchestra that is heard here (and former music director of the Finnish National Opera).

There will probably never be an absolute “best” recording of this remarkable work. It has twenty singing roles divided among eight or so singers, all in a work that lasts some 43 minutes. Characters rarely sing at the same time, and some passages are choral or orchestral. Thus, as simple arithmetic tells us, each role contains only a few minutes of singing!

The singers on this recording characterize their various roles vividly and, in a few cases (Grandfather Clock, Fire), are more precise with the pitches and articulation than are the singers in the Denève recording. I was surprised that the two singers who participate in both the Denève recording and this one (Pasturaud and Piolino) seem even more in command in this concert recording than they already were when they had the advantage of studio conditions and the possibility of multiple retakes. Perhaps the presence of an audience that could understand, without supertitles, the nuances of the text that was being sung, made a difference.

The discovery for me is Sabine Devieilhe, as Fire, Princess, and Nightingale. Her coloratura singing is as close to perfection as humanly possible. Her lyrical singing is no less wondrous. I hope to hear her in much other repertoire soon. (I have read praise of her three recital discs for the French firm Erato.) I must also praise three of the other singers who, like Devieilhe, were not on the Denève recording. The renowned Nathalie Stutzmann brings enormous warmth and seeming spontaneity to her three roles. Jean-François Lapointe takes care to sing, not talk-sing, Grandfather Clock. And, as the Child, Chloé Briot reveals her impressively diverse vocal abilities ever more as the opera unfolds. (Briot has a touch of wobble on sustained notes, but is otherwise perhaps the best Child on any recording.) The four “animals” who speak, near the end of the opera, are members of the French Radio Chorus, and the booklet nicely names them. They do their lines superbly.

The libretto is given complete, including the extensive stage directions, all in the superb old Felix Aprahamian translation. But the latter could use a bit of updating or clarification by now. For example, the character known as La Bergère is translated as The Sofa, which seems to imply a largish object. But the stage directions make clear that this piece of upholstered furniture is smaller than the big armchair (Le Fauteuil, sung by a bass), which of course is why Ravel assigns the role to a higher voice (mezzo-soprano). Perhaps we might call it (or her) a “Small Upholstered Seat.”

In addition to famous older recordings (see the previous review), I should add that there are two different Glyndebourne DVD versions of this opera. Both pair the work with Ravel’s first opera, L’heure espagnole, and both are apparently wonderful in different ways.

The opera comes as part of a 2-CD set, with two works by Debussy. One is another “child” work: Debussy’s The Prodigal Son (1884). Of course, this child is fully grown, for the story is the one in Luke 18 about a son who has left his father and brother and wasted his inheritance, then returns and is forgiven. The other work is a little-known early symphonic movement.

There is much less recorded competition for the Debussy cantata (or, in its alternate title, “operatic scene”) than for Ravel’s opera. And for good reason: it’s an early work, composed to please the professors at the Conservatoire and help win Debussy the Prix de Rome. (It succeeded!) Debussy was pleased enough with it to allow it to be published twenty-four years later. Still, whole chunks of it sound highly conventional. My favorite passage is the opening prelude, which is clearly meant to sound exotic—in the manner of Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, and Balakirev—so as to place the listener in the ancient Middle East.