February 27, 2019

Mozart: Così fan tutte - Royal Opera House

Sir Thomas Beecham was probably over-egging it a little when he described Così fan tutte as resembling “a long summer day spent in a cloudless land by a southern sea”. Very little - actually none - of that comes across in this production, but there is something to be said for the lithe, effortless way in which the conductor, Stefano Montanari, keeps the music moving. The delicacy of Mozart’s scoring, the beautiful - almost tangy - woodwind phrasing were played like lyrical instrumental waves rippling through the orchestra. This had the benefit of focusing attention on Mozart’s glorious ensembles and arias which sounded fresh enough to leap off the pages of the score - and there was no lack of soul-searching in many of the solos. Beecham may have been right after all.

Paolo Fanale as Ferrando, Serena Malfi as Dorabella. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Paolo Fanale as Ferrando, Serena Malfi as Dorabella. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

I’ve always rather sided with those - perhaps an unfashionable view to hold these days - who find the libretto and plot of Così slightly weak and rather concocted. Given the length of the opera, Mozart - rather uncharacteristically - doesn’t develop the motives of fidelity and honour completely satisfactorily. But that is not to say there aren’t complex attitudes towards femininity and love because there are. Gloger’s production does little to enlighten us, however. There is perhaps some truth in the view that Mozart was a largely theatrical composer when he came to writing his operas so Gloger’s idea of setting the whole work in Alfonso’s ‘theatre’ seems a logical extension of this. But that overwhelming ambition Gloger has to be theatrical glosses over what is so disturbing about this opera. Often, I thought I was sitting through scenes from a Comedy of Errors or a Midsummer Night’s Dream. Gloger’s production is so literally theatrical it forgets that Così is a heavily ambivalent opera, almost a little unnerving in its treatment of women. It’s such a comic tour de force (and this production is very funny, the play between Orendt’s Guglielmo and Fanale’s Ferrando almost recalling Laurel and Hardy at times) that self-knowledge is either taken for granted or simply elided over altogether.

For Gloger, Don Alfonso’s theatre is viewed entirely as an experiment, a laboratory in which to match-make and explore the complexities of love and fidelity. Arguably, his reasoning has as much to do with the psychology of the process as it does with the emotional circumstances of it but it’s the very concept of the multiple scene changes which makes the whole production such a chaotic - and often crowded - flop. It begins off stage from one of the opera boxes which, depending on your point of view, either draws the audience in, or does the opposite; likewise, a tendency to place the scenery to the forefront pushes the singers too far forward for no demonstrable purpose other than to make the production seem small in scale. Proscenium arches give height, but they’re often so bleak - a simple black brick wall, for example - that the singers seem to be squeezed into the centre of them as if you’re watching them on a television screen. A railway station with a vast clock is almost occluded in smoke; a brightly lit steel-framed cocktail bar (rather better done by Bieito, I seem to remember), a semi-wilting tree with an unconvincing serpent wrapped around it didn’t really convince me. Muscled stage hands, with tattoos, or cigarettes between their lips, shifting scenery or drawing up backdrops merely add to the clutter.

Where the production has a strength is that it advances the contemporaneous nature of relationships from its original setting. The idea that a modern day Così might demonstrate that couplings can be torn apart by infidelity and betrayal isn’t revolutionary but Gloger stops short of being truly shocking as Bieito (in his Don Giovanni) didn’t. Gloger’s Guglielmo ends up becoming a slightly tragic figure for whom love is an empty vacuum; Ferrando comes closest to the ideal of faithfulness but only because he recognizes he is in danger of abandoning it altogether. Dorabella doesn’t seem to know what she wants. Fiordiligi becomes the most deceitful and confused of all. Alfonso’s experiment might be seen as the masterful duplicity and manipulation that it is - just as Despina’s disguises are masks of elaborate confusion. All of these aspects of love collide and entangle in this production even if you don’t necessarily grasp it by the end.

Serena Malfi as Dorabella. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Serena Malfi as Dorabella. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

In a way, it’s quite surprising given how I generally didn’t warm to the production how riveting I found much of singing. Much of this was beautifully sung - and exquisitely - if perhaps - a little over-acted. Così fan tutte undeniably contains some of Mozart’s most ravishing music and the casting here was nigh ideal in balancing the voice colours. There was some unanimity in the bass-baritone of Gyula Orendt’s Guglielmo and the tenor Paolo Fanale’s Ferrando - the parallels of warmth and contrast to the voices were like the equivalent of a harmonious echo. Salome Jicia’s Fiordiligi was gloriously pitched, Serena Malfi’s Dorabella a little more understated - but rich enough and fully convincing. Thomas Allen’s voice has waned a little - but no one sings the role of Alfonso with more irony, or sheer joy - and today there are just hints of tragic overtones to it. Serena Gamberoni’s Despina was a glorious portrait in wit and soubrette and deliciously funny.

That richness in Serena Malfi’s voice was magnificent in ‘Smanie implacabili’ - taken with a beautiful soaring line and an almost tragic intensity. Stefano Montanari tended to drive the music fast - especially in Act I - so if Malfi were intent on bringing some added depth to her singing it wasn’t always apparent. The prominence that Montanari gave to the woodwind, however, was often a sublime foil against the warmer richness of Malfi’s voice - even at these brisk tempos. Oddly, he seemed to slow down for Ferrando’s ‘Un’aura amarosa’ which was perhaps the highlight of Act I. The sheer beauty, the beguiling tonal colour, the careful phrasing and the ability to hold the most exquisitely shaped pianissimo were simply jaw-dropping. It’s the only time throughout the opera you felt a singer was entirely drawing the audience into this rather self-destructive world - a quite magical moment. If there was a wonderful serenity to much of Fanale’s singing - and he never really felt constrained by the intensely lyrical size of his tenor voice - Orendt’s Guglielmo rather revelled in the vast comic scale of his arias. It’s not just that the voice is so large, but it’s that it also has such a developed and innate sense of character. The voice can sound mocking one moment - almost like a foil to Thomas Allen’s Don Alfonso - but the next it seems to imitate the orchestra - how some of Orendt’s notes rang out against some of the brass fanfares, as if in a comic duet, was thrilling. Salome Jicia was colossal in her ‘Fra gli amplessi pochi astanti’ - thrilling in her high notes and riding over the orchestra, somehow seeking to assert her dominance over both the men as her prospective lovers.

Stefano Montanari - making his house debut - managed to get the Royal Opera House orchestra to play with a lightness of touch which was admirable. The opening to Act II can - in the wrong hands - sound like a Bruckner adagio and Montanari came close to making it do so. But at his best, which was much of the time, this was a performance of the score that was fleet and, shrewdly, highlighted individual instruments within the orchestra. There was a period feel to all this - without it overtly being one.

Covent Garden’s Così fan tutte is one that is predominantly rescued by the singing and conducting; it would, largely, sink without a trace if that weren’t the case.

Marc Bridle

Paolo Fanale - Ferrando, Gyula Orendt - Guglielmo, Thomas Allen - Don Alfonso, Salome Jicia - Fiordiligi, Serena Malfi - Dorabella, Serena Gamberoni - Despina; Jan Phillip Gloger - Director, Stefano Montanari - Conductor, Julia Burbach - Revival Director, Ben Bauer - Set Designer, Karin Jud - Costume Designer, Bernd Purkrabek - Lighting Designer, Royal Opera House Orchestra & Chorus.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; 25th February 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/6970%20Gyula%20Orendt%20as%20Guglielmo%2C%20Thomas%20Allen%20as%20Don%20Alfonso%2C%20Paolo%20Fanale%20as%20Ferrando%20%28C%29%20ROH%202019.%20Photographe%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Così fan tutte: Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id= Above: Gyula Orendt as Guglielmo, Thomas Allen as Don Alfonso, Paolo Fanale as FerrandoPhoto credit: Stephen Cummiskey

Gavin Higgins' The Monstrous Child: an ROH world premiere

Following somewhat in the line of Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Coraline - last year’s premiere for children - Gavin Higgins’s The Wondrous Child, to another libretto by a children’s author, this time Francesca Simons, seems to me to have a good chance of prospering not only in that specific role, but also more generally. It is certainly a successful first opera - from the Linbury, from Higgins, from Simons, and indeed from the production team and performers, without which any single effort would likely come to naught. Opera, we were reminded, is above all a company effort - which should, of course, include the audience too. Let us hope, then, that plenty of teenagers were among those who were able to secure tickets before the run sold out; and/or that further tickets will be released, as often happens in practice.

Many - though perhaps not so many of us on the first night - will doubtless come to the opera through Simons’s book ‘of the same name’, as Peter Cook and Dudley Moore might have had it. Not that there is anything of ‘Little Miss Britten’ here; for not only is the plot drawn from Norse mythology, from the myth of Hel, goddess of the dead; the libretto is distinctly on the Anglo-Saxon and perhaps even the Norse roots of the English language. Had his English been better, Wagner might have lauded the lack of Latinism. The immediacy, not to mention the ‘earthiness’ of some of the vocabulary make particular sense in a primaeval realm - and will surely appeal to teenagers of all ages in the audience too. To a certain extent, staging and score work with that, performances perhaps still more so; they also recall (to us), however, consciously or otherwise, that we are no more Anglo-Saxons than we are Norse gods. The false immediacy of which Wagner could occasionally - very occasionally - prove guilty in theoretical, though never dramatic, writing stands always in need of puncturing in our modern condition. That is not a value judgement, simply an observation.

Hel Puppet. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Hel Puppet. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Simons knows that as well as Higgins, as well as by director, Timothy Sheader and his team. And so, we are reminded by the puppetry in the first half of the staging, actors and singers lightly detached - this is not The Mask of Orpheus, nor does it try to be! - from their characters in some cases, as well as by Hel’s narration of that first part, the later character recounting the deeds of the child-puppet her, that even in - particularly in - a drama dealing with (supposedly) eternal gods, time plays a mediating role. Again, Wagner of all musical dramatists could have told us that - and does. Higgins offers much in the way of readily associative and memorable leitmotifs in his score, as well as plenty of ‘atmosphere’ and ‘action’, after a fashion that would surely make sense to teenagers - and others - accustomed to the ways of film scores, without ever sounding ‘like’ film music. Video and electronic sound help us shift between locations, for instance from the gods realm in the skies to the place of Hel’s banishment, from which she will bring about the end of the gods’ rule.

Leaving aside the (understandable) exaggeration about what opera ‘is’, for it can be any number of things, one knows what Simons means when she writes in the programme: ‘It took me a while to understand how different writing a libretto is to writing a novel. Opera is much more direct: people say what they think - repeatedly. Opera is so heightened, it really is the perfect way to express the emotion and epic sweep of myths about gods and giants, love and hate, as well as a young girl’s journey towards creating her own life.’ To my mind - and increasingly on reflection - Simons and Higgins achieve this with great success here. Pacing is different too; the analogy Simons draws with a picture book - ‘the words need to allow space for the illustrations’ - is interesting. Again, one senses a true collaboration: between librettist and composer, of course, but also with the production team and performers.

Graeme Broadbent as Odin and Marta Fontanals-Simmons as Hel. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Graeme Broadbent as Odin and Marta Fontanals-Simmons as Hel. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Marta Fontanals-Simmons gave a fine performance as Hel: half goddess, half corpse. Never sentimental - she does not want mere pity - she involved us in her plight, her hopes, her decision through sheer force and variety of vocal personality. Rosie Aldridge and Tom Randle impressed and (not a little) repelled as her parents: those who cursed her and ultimately the world by bringing her into it. Lucy Schaufer proved typically compassionate as the giantess Modgud, keeper of the bridge to Niflheim and the dead. Odin, king of the gods, received a sharply observed performance from Graeme Broadbent, taking us plausibly from hauteur to downfall. Dan Shelvey’s Baldr, as carefree and compassionate in tone as the lovelorn Hel thought him, offered a performance both delightful and moving. The Aurora Orchestra under Jessica Cottis could hardly have offered surer advocacy in the pit.

Mark Berry

Hel: Marta Fontanals-Simmons; Angrboda: Rosie Aldridge; Loki: Tom Randle; Modgud: Lucy Schaufer; Baldr: Dan Shelvey; Odin: Graeme Broadbent; Nanna, Thora: Elizabeth Karani; Actors and Puppeteers: Laura Caldow, Stuart Angell. Director: Timothy Sheader; Designer: Paul Wills; Lighting: Howard Hudson; Video: Ian William Galloway; Movement: Josie Daxter. Sound Intermedia/Aurora Orchestra/Jessica Cottis (conductor).

Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House, London, Thursday 21 February 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Monstrous%20Child.png image_description= product=yes product_title=The Monstrous Child, by Gavin Higgins: a world premiere at the Linbury Theatre, ROH product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id= Above: The Monstrous ChildPhoto credit: Stephen Cummiskey

February 26, 2019

Elektra at Lyric Opera of Chicago

In the title role of Elektra Nina Stemme’s multi-faceted portrayal commands attention, even during moments of silence or merely by an implied presence. Elektra’s sister Chrysothemis is sung with wrenching urgency by Elza Van Den Heever. Their brother Orest, as portrayed by Iain Patterson, is an emotionally committed figure whose heroic stature emerges in response to requisite action. Klytämnestra and Aegisth are performed by Michaela Martens and Robert Brubaker. Donald Runnicles conducts with masterful control the Lyric Opera Orchestra. Mme. Stemme and Messrs. Patterson, Brubaker, and Runnicles make their Lyric Opera of Chicago debuts in these performances.

Despite the protagonist’s absence in the initial scene, her essence pervades the steps of the palace. In answer to the question, “Wo bleibt Elektra?” (“Where is Elektra?”), the orchestra supplies a response: Runnicles elicits a palette of darting colors and fractured chords from the Lyric Opera Orchestra as if to suggest the patterns that have altered any sense of Elektra’s equilibrium. Once she appears and commences her monologue, Stemme’s Elektra wavers between controlled reflection, expressed piano, and flights of hysterical determination delivered with piercing top notes. The horror of her father’s murder and the subsequent transformation of the royal linger here in cries of anger yet also in shudders of repulsion. This trajectory of identification with Elektra’s persona grows only deeper throughout the evolution of Stemme’s performance.

Vital to this production, and in the spirit of Strauss’s conception, is Elektra’s interactions with others – both in and beyond her immediate family. The hesitant notes expressed by Van Den Heever’s entrance prompt Elektra to dwell on the potential malleability of her sister in securing an ally. The voices of both sopranos mingle, at rimes, in lyrical union until the failure of any cooperation becomes clear to the initiator of vengeful plans. Stemme’s subsequent confrontation with Klytämnestra enhances the tensions between two figures neither of whom will yield her ground. Martens does not rely on caricature to define the self-contained cause of Elektra’s anguish. Instead, she faces her daughter with the attempt at composure while inadvertently succumbing to glances of apprehension. Martens’s departure reflects a forced attitude of dignity since he has stared into the eyes of gleaming justice. Elektra’s encounter with Orest and the ultimate realization of her plan shows the complexity of Stemme’s approach reminiscent of the earlier monologue. She is at first cautious, then peals of controlled emotional relief sweep over the Grecian princess. After the moving scene of recognition, there is still work to be done. Patterson is especially effective as Orest: a growing resonance pulses in his voice as he nears the moment of revealing his identity. Once Elektra sends him into the palace, Stemme’s portrayal begins a final transformation. Her frantic search for the forgotten axe sways into the triumphant cry of “Triff noch einmal!” (“Strike once more!”) as Klytämnestra ‘s shrieks resound from within the palace. In a final semblance of control the daughter of Agamemnon leads Aegisth to his punishment when he comes tripping along in a daze of confusion. Stemme’s play of gentility here costs her final shred of stability. When she initiates her dance in this production Stemme appears in an apotheosis of light, so different from the grey and dull tones of the struggles highlighted earlier in this production. As she falls lifeless, the light is extinguished, her task is done, the surviving siblings must persevere in her spirit.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Nina%20Stemme_ELEKTRA_Lyric%20Opera%20of%20Chicago_37A9949_c.Cory%20Weaver.jpg image_description=Nina Stemme as Elektra [Photo © Cory Weaver] product=yes product_title=Elektra at Lyric Opera of Chicago product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above: Nina Stemme as Elektra [Photo © Cory Weaver]Handel Singing Competition semi-finalists announced

The adjudicators for this year’s Competition include Ian Partridge CBE, Catherine Denley, Michael George, Lawrence Zazzo, Rosemary Joshua and Jane Glover. The semi-finalists will be accompanied on harpsichord and will each sing for fifteen minutes in an all-Handel programme. Five or six singers will proceed to the final in April and will be accompanied by the London Handel Orchestra and Laurence Cummings, musical director of the London Handel Festival. St.George's, Hanover Square is of course the church where Handel himself worshipped, and the Festival continues his great tradition of nurturing young talent through the Handel Singing Competition.

All of the finalists are between 23 to 34 years old and will be competing

to win one of four prizes: First Prize (£5000), Second Prize (£2000),

Audience Prize (£500) and the Finalist Award (£300).

"I am thrilled with the response to the Handel Singing Competition

this year, with a record number of applications from across the world,

demonstrating that this is a truly international event. Congratulations

to all the Semi-Finalists - we look forward to hearing you all on 5

March!"

Samir Savant, Festival Director - London Handel Festival

The Handel Singing Competition has been held annually since 2002 and has

grown year on year, aiming to continue Handel’s tradition of nurturing

young talent. Past finalists include Ruby Hughes, Iestyn Davies, Lucy

Crowe, Tim Mead, Sophie Junker and Anna Starushkevych. The Competition

works with an impressive line-up of adjudicators, and past judges include

James Bowman, Iestyn Davies, John Mark Ainsley and Rosemary Joshua. All of

the finalists from this year’s Competition are guaranteed a lunchtime

recital in the 2020 London Handel Festival.

https://www.london-handel-

Longborough Festival Opera founders to receive Wagner Society award

The award comes as Longborough announces its new Ring cycle, following their critically acclaimed 2013 cycle which established the festival as a destination for Wagnerians around the world.

Lizzie Graham comments: “Martin and I are delighted to receive this award on behalf of the whole team at Longborough who work so hard to make Wagner successful here, and are currently helping to put our new Ring cycle in place.”

The entire cycle will be conducted by Longborough Music Director and eminent Wagnerian Anthony Negus, and brought to life by Royal Opera House Head Staff Director Amy Lane. Lane is currently Co-Directing Drot og Marsk with Kasper Holten at the Royal Danish Opera and was recently Associate Director on Die Walküre and Gotterdammerung on Keith Warner's Ring cycle at Covent Garden.

“The Ring cycle is the most epic of tales with a score that is searing, desperate, sublime and so perfectly unfathomable,” comments Amy Lane. “What an honour it is to set foot upon this glorious pathway and to commence this journey with Longborough.”

Martin and Lizzie Graham will receive The Reginald Goodall award at a ceremony at The Royal Over-Seas League in London on 20 March 2019. Previous recipients include Bernard Haitink, Sir Antonio Pappano, Sir John Tomlinson, Plácido Domingo and Longborough Festival Opera’s own Music Director Anthony Negus (2017).

Six Charlotte Mew Settings: in conversation with composer Kate Whitley

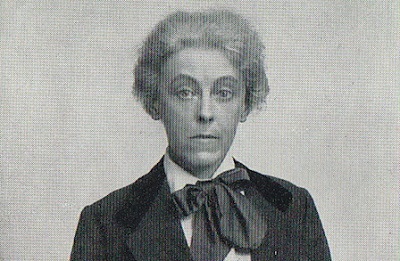

When Mew died in 1928, the obituary in the local newspaper was painfully terse: ‘Miss Charlotte Mary New [sic], ... a writer of verse.’ Today, while Mew’s poetry is admired by a small but ardent group of devotees, her name remains largely unfamiliar, although a forthcoming biography of Mew by Julia Copus, to be published by Faber, will bring the poet’s life and work into the public eye.

It was a life of tragedy and torment, illness and incarceration. Mew’s aunt and uncle, on her mother’s side, both suffered from insanity and were institutionalised. Of the seven children of Frederick Mew, a struggling architect, and Anna Kendall Mew, only four survived childhood. When she was nineteen, Charlotte’s eldest brother, Henry, afflicted by what would now be diagnosed as schizophrenia was sent to a mental institution, where he spent the last thirteen years of his life. Charlotte’s younger sister, Freda, then in her early teens, was similarly plagued. Financial hardship followed Frederick’s death in 1898 and Charlotte, her sister Anne, and their mother moved into a rented home, subletting the upper floor and eking out a frugal existence. Her mother died in 1923, and when Anne succumbed to cancer four years later Charlotte began to suffer from delusions. When, in February 1928, she was diagnosed as neurasthenic, she voluntarily entered a nursing home, where on 24 March she committed suicide by drinking Lysol. [1]

Diminutive, prone to wearing dull men’s suits, swearing and smoking with equal vigour, Mew must have cut an odd figure even among the poets who gathered at Monro’s Poetry Bookshop. Mew apparently told her friend Alida Monro that she and her sister had determined early in life ‘that they would never marry for fear of passing on the mental taint that was in their heredity’ - perhaps influenced by the prevailing new theories in eugenics. Her lesbianism only intensified her feelings of isolation and alienation.

Charlotte Mew.

Charlotte Mew.

However, beneath her reserved and reclusive manner, passion burned fiercely. Though reluctant to recite her poetry at public readings, when she did accept an invitation Mew startled the audience: ‘They sat facing the little collared and jacketed figure, with her typescripts and cigarettes … Once she got started (everyone agreed) Charlotte seemed possessed, and seemed not so much to be acting or reciting as a medium’s body taken over by a distinct personality. She made slight gestures and used strange intonations at times, tones that were not in her usual speaking range.’ [2]

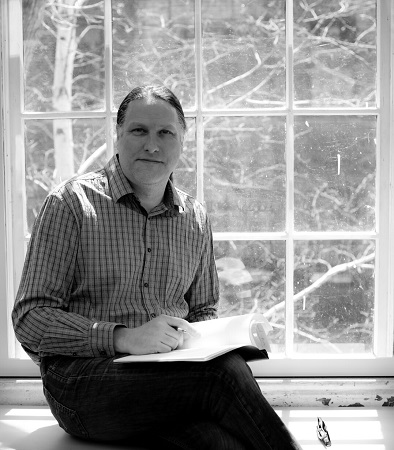

Mew’s poetic voice is soon to be heard again, in a new expressive form. Composer Kate Whitley has set six of Mew’s poems for soprano, bass and strings, and these songs will be presented as part of a special concert at Temple Church, London on Tuesday 30 April . The programme has been curated by bass Matthew Rose, and brings together soprano Katherine Broderick, pianist Anna Tilbrook and violinist Jan Schmolck to celebrate music for voice commissioned by the Michael Cuddigan Trust. Also on the programme is the world premiere of a new work by David Bruce, plus Martin Suckling’s Songs from a Bright September, works which were similarly commissioned by the Michael Cuddigan Trust, of which Rose himself is a trustee. Rose comments, “Michael Cuddigan, along with his wife Anne, were so kind to look after me as a student in Aldeburgh for many years. Michael had the most amazing love for music and musicians, and we started this Trust five years ago in his memory. I’m greatly looking forward to this exciting evening of new works performed by some of the country’s leading musicians.”

Matthew Rose. Photo credit: Lena Kern.

Matthew Rose. Photo credit: Lena Kern.

Kate is a composer-pianist and co-founder of The Multi-Storey Orchestra, which, from its base at Bold Tendencies car park in Peckham, takes professional performances to local schools and further afield. She has frequently striven to take classical music into new contexts and before new audiences. Her concert piece, Sky Dances, was performed at Trafalgar Square as part of a programme that brought together the LSO, the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, and 70 young musicians from East London. Paws and Padlocks, a children’s opera about two children who get trapped overnight in a zoo, was performed at Blackheath Halls in 2016, while Speak Out, which set words by Malala Yousafzai, was performed by BBC National Orchestral and Chorus of Wales on International Women’s Day 2017 in support of the campaign for better education for girls. NMC Recordings released a CD of her music, I am I say , in 2017.

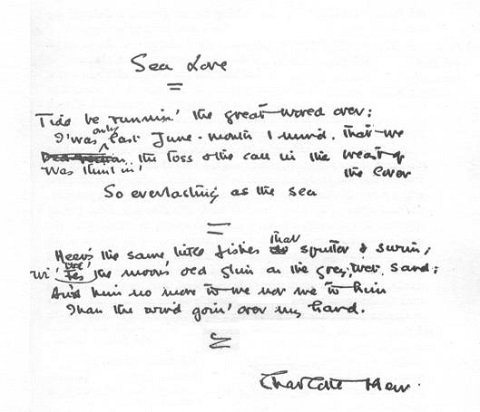

I ask Kate what it was that had drawn her to Mew’s poetry. She explains that the initial impetus came from Sir Stephen Oliver, a Trustee of the Michael Cuddigan Trust and the great-nephew of Mew’s life-long friend Ethel Oliver, who got in touch with Kate and, giving her copy of Mew’s collected works, suggested that she might compose some settings. Kate had never heard of Mew but found the poems instantly appealing and absorbing; she discussed Mew’s work with Julia Copus, whose knowledge and love of the poems were of enormous value as she guided Kate’s selection of three poems, her choice being influenced by length and theme. ‘The Farmer’s Bride’ was framed by two shorter poems, ‘Rooms’ and ‘Sea Love’, and these three songs were performed by Matthew Rose and the Albion Quartet in Orford Church in June 2017. Kate has now composed three further settings - ‘I So Like Spring’, ‘Absence’ and ‘Moorland Night’ - which will be sung by Katherine Broderick on 30 April.

Mew strips bare the inner lives of her poet-speakers, with often painful honesty. There is a driving tension between restraint and release - as if Mew wants both to speak out and hold back. Images of confinement allude to the social structures which force women into emotional, physical and financial dependency on men. But, for all her personal idiosyncrasies, Mew was no ‘New Woman’, and remained a Victorian in her social outlook, lamenting the loss of old certainties as the world moved forward into the age of modernity, of uncertainty and crisis. I wonder whether Kate finds, as I sometimes do, the wrought emotional intensity of Mew’s poems somewhat overwhelming? On the contrary, Kate tells me, that it was this very intensity, conflict and rawness which she found so moving.

Alida Monro reproduced this corrected manuscript of Sea Love in the 1953 Collected Poems. The manuscript is now in the Buffalo Collection.

Alida Monro reproduced this corrected manuscript of Sea Love in the 1953 Collected Poems. The manuscript is now in the Buffalo Collection.

She was, though, initially a little daunted to be confronted with texts so different from anything else she had previously set to music. The rhyming couplets of ‘The Farmer’s Bride’ and the regularity of the form of ‘Sea Love’ seemed to demand regular phrase shapes, an approach to text-setting which was contrary to Kate’s usual, instinctive practice. But, in the event, the way the poetic form imposed itself upon the musical form was a positive stimulus, for it seemed to offer a way of capture the tenor of Mew’s world and our distance from the historical past: “It felt natural to compose in this way; it was the best way to communicate what the poem says.”

‘The Farmer’s Bride’ is a man’s account of his marriage to a woman who rejects his attentions and demands. One night she escapes but is hunted down by her husband and other villagers who find her among a flock of sheep. The crowd ‘caught her, fetched her home at last/ And turned the key upon her, fast’. She submits to the conventions of domesticity, ‘So long as men-folk keep away’, and each night climbs a stairway: ‘sleeps up in the attic there/ Alone, poor maid’. I wonder if Kate hears the speakers in Mew’s poems as being male or female? The speakers in Kate’s second set of poems could be either, she says, but it’s a male voice we hear in ‘The Farmer’s Bride’. We never actually hear the voice of the young girl after whom the poem is named, and this is the point - she is described from the male point-of-view, a ‘madwoman in the attic’:

Three summers since I chose a maid,

Too young maybe—but more’s to do

At harvest-time than bide and woo.

When us was wed she turned afraid

Of love and me and all things human;

Like the shut of a winter’s day

Her smile went out, and ’twadn’t a woman—

More like a little frightened fay.

I agree with Kate that here Mew assumes a male voice in order to communicate strong erotic desire: the man’s lament is not for his young bride’s sadness and suffering, but for his own unfulfilled desire.

Katherine Broderick.

Katherine Broderick.

The image of the locked room or enclosed space recurs repeatedly in Mew’s poems, exposing her loneliness, and we find it elsewhere in Kate’s settings. ‘I remember rooms that have had their part/ In the steady slowing down of the heart’ says the speaker in ‘Rooms’, noting that ‘The room is shut where Mother died’. The word ‘shut’ reappears in ‘Absence’ - ‘In sheltered beds, the heart of every rose/ Serenely sleeps to-night. As shut as those/Your guarded heart;’ - and ‘Moorland Night’: ‘My eyes are shut against the grass’.

These poems have a dramatic lyrical tone, but the rhythms are restless as the forms frequently juxtapose extremely short and long lines which tug against the underlying meter, and the rhyme schemes are complex. I wonder whether these formal idiosyncrasies were disinclined to lend themselves to musical setting? Again, Kate seems to have found such elements creatively inspiring. She describes the way in which the voice and strings work together, sometimes the voice leading and the strings accompanying, elsewhere the strings coming to the fore between the lines or at the end of stanzas, and this seems to me to imitate the restless conflicts and tensions within the poems.

‘Moorland Night’ is the final poem in The Farmer’s Bride. Here, Mew seems to find resolution in nature:

My face is against the grass - the moorland grass is wet -

My eyes are shut against the grass, against my lips there are the little

blades,

Over my head the curlews call, And now there is the night wind in my hair;

My heart is against the grass and the sweet earth, - it has gone still, at

last;

It does not want to beat any more,

And why should it beat?

This is the end of the journey.

The Thing is found.

In an essay, ‘The Poems of Emily Brontë’, which is printed in Mew’s Collected Poems & Prose, Mew described Brontë as ‘a self-determined outlaw’, ‘a soul which scorns the world with masterful persistence and disclaims all comradeship save that of the “strange visitants”’. Brontë’s poetry is, she says, ‘dominated by a note of pure passion … a passion untouched by mortality and unappropriated by sex, the passion of angels, of spirits, redeemed or fallen, if such there be and sorrow of an ever-unsatisfied desire, she looked out upon the world, which the sad circumstances of her environment, together with the gloomy bias of her nature, showed so dark, with a curious indifference and mistrust’.

These words might equally describe Mew and her own poetry.

Kate Whitley’s Six Charlotte Mew Settings can be heard at Temple Church on 30th April 2019.

Claire Seymour

[1] See Charlotte Mew: Collected Poems and Prose, ed. Val Warner (London: Carcanet Press/Virago Press, 1982).

[2] Penelope Fitzgerald, Charlotte Mew and Her Friends (London: Collins, 1984), 111.

Photo credit: Ambra Vernuccio

February 23, 2019

Expressive Monteverdi from Les Talens Lyriques at Wigmore Hall

It gave us a welcome opportunity to hear the zest and zip of Christophe Rousset’s Les Talens Lyriques - Rousset, stood with his back to us, his hands hovering with vivid alertness above the keyboards of the organ and harpsicord, a bundle of bristling energy - and to appreciate the expressive talents of three singers who, though familiar and esteemed presences in the concert halls and opera houses of Europe, are less frequent visitors to these shores.

‘Chiome d’oro’ from the Sixth Book of Madrigals (1619) got things underway, the entwining tenor voices of Swedish haute contre Anders J Dahlin and Norwegian Magnus Staveland spinning ‘tresses of gold’: there was joy and lightness of spirit, and a combination of precision and elasticity in their silkily unfolding phrases and melismas; and, the fluctuation of tempi gave the impression of being both flexible and controlled, as the music conveyed the sweep of varied emotions. The mood was never too earnest and retained its playful bite. Both singers studied in Copenhagen, Dahlin at the Royal Conservatory of Music and Staveland at the Royal Opera Academy. They joined forces again in ‘O sia tranquillo il mare’ (Whether the sea be calm) from the Eighth Book, Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi, and here they exploited every wonderful dissonance, ‘Mai da quest ’onde io non rivolgo il piede’ (I shall never again turn my steps back to this ocean), throbbing with the pain of betrayal. As the strength of their lamentation for the faithlessness of the poet-speaker’s beloved was expressed in a musical shudder, both body and soul grieved. A poignant tierce de Picardie, ‘E spesso ancor t’invio, per messagieri’ (often I send messages to you), seemed to suggest a hope which then proved false, as the tenors swelled through their pain: ‘A ridir la mia pena, e’l mio tormento’ (to tell you repeatedly of my pain and my torment). Coming together in the closing, summative lines, they articulated the moral - he who entrusts his heart to a lady and his prayers to the wind, can hope for no mercy - in dark, low voices. This was a performance that was at once visceral, spontaneous and expressively calculated to make its effect felt.

Between these tenor duets, soprano Eugénie Warnier performed ‘Quel sguardo sdegnosetto’ (That disdainful little face) from the second book of Scherzi musicale (1632). I enjoyed the strong sense of engagement between the voice and Isabelle Saint-Yves’ cello line, and the flashes of joy which propelled the music towards its triple meter, though I found Warnier’s tone a little ‘white’: pure and clean, yes, but full and diverse enough to capture every drop of nuance that Monteverdi squeezes from the text? - I wasn’t so sure. And, the very purity of the sound, here and elsewhere in this performance, made the tuning of some cadential phrases difficult to secure, as the floating soprano hovered rather than skewered the pitched, while the string and continuo issued a grainier hue. Warnier’s sensitive performance of ‘Ohimè ch’io cado, ohimè’ (Alas, I am falling, alas) - the ending was exquisitely still and poised - was preceded by Giovanni Kapsberger’s Sinfonia prima à 4 con due bassi (1615). Here, we enjoyed the balletic violin fingering of Gilone Gaubert and Virginie Descharmes which flirted with Angélique Mauillon’s harp and the ripples of Laura Mónoca Pustilnik’s lute, a silky ribbon against the gravellier organ and cello timbre. Was Kapsberger’s Sinfonia offered as an instrumental complement to Monteverdi’s experiments with vivid declamatory expression? Or as a palette cleanser? Or simply to give the singers a rest? The Sinfonia was not mentioned in Alexandra Coghlan’s programme note, and no other items by Kapsberger, or for instruments alone, were performed.

Scalding dissonances returned in the tenors’ duet, ‘Ardo e scoprir, ahi lasso, io non ardisco’ (I burn and, alas, I do not dare to reveal); there was delicious bittersweet-ness which epitomised the contemporary aesthetic - ‘Per trovar al mio mal pace e diletto’ (to find, in my woe, peace and delight’ - and wonderful gradations of intensity as the rhetorical fragments formed a cogent whole. The first half concluded with the ‘Lamento d’Arianna’ from Arianna. Oh, that more of this contribution to the commemoration of the marriage of Francesco Gonzaga and Marguerita of Savoy was extant! One wonders what the newly-weds made of this ‘celebratory’ expression of such pain and torment … a suffering which, perhaps, expresses a sorrow bound up with Monteverdi’s own dissatisfaction, grief and restlessness in 1608. As early as 1601 he had written to the Mantuan Duke expressing his concern that court intrigues might deprive him of his place, and recording his affliction by illness, poverty and overwork, and a talent overlooked. In September 1607 his wife died; two weeks later Monteverdi was summoned to Mantua to write Arianna for a wedding which would take place by proxy in Turin in February 1608 and be celebrated in Mantua with two weeks of festivities in May 1608. The title role was to have been taken by Catérina Martinelli, pupil of Monteverdi’s wife who had lived with him from 1603, but in March 1608 she died of smallpox and the role was sung by Virginia Ramponi: she was reputed to have learned the part in six days and her emotive performance to have moved many to tears. No wonder that Monteverdi later remarked that Arianna had almost caused his own demise.

Warnier moved with freedom and naturalness through the lyrical arioso - the vocal line is less rhythmically complex that the idiom of Orfeo - and fused music and language to express deep and diverse human emotions. Her soprano was quite withheld at the start, allowing the harp and lute to articulate the sentiments of the text, and the escalation of intensity and rhetoric was admirably controlled, as was the responsiveness of the instrumental lines to the voice. I wondered, though, whether it was wise to position Warnier in the centre of the Wigmore Hall platform behind the instrumentalists: could those seated directly behind Rousset see her at all? So much depends not just on the vocal expression but on the ‘lived’ embodiment of emotion: one thinks of the Three Ladies of Ferrara, famed as much for the luxuriant effusiveness of their manner and presentation as for the beauty of their voices and their ability to execute elaborate ornamentation.

After Warnier’s rendition of ‘Si dolce è’l tormento (So sweet is the pain), the second half of the programme was dominated by Monteverdi’s Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda - based on Tasso’s mock-chivalric account in Gerusalemme liberate of the duel between Tancredi, the Christian soldier, and Clorinda, the Muslim warrior he loved, which ends with the death of Clorinda - which was composed in 1624, commissioned by Monteverdi’s patron Girolamo Mocenigo.

Interestingly, in comparison to the 1607 Orfeo, the practicalities of the premiere of which we know little, Monteverdi took great care to describe how this work should be performed - details which, for obvious reasons of practicality were not realised here. The two combatants were to be armed, Tancredi arriving ‘on horse’, Clorinda from the other side. There was to be no scenery. The instrumentation was also unusually precise: four viola da gamba. And, Combattimento should follow swiftly from the preceding madrigals in Book Eight, without gesture, with no warning. Clearly Monteverdi was determined it would make the utmost theatrical and expressive effect.

Here, such ‘effect’ was largely due to Staveland’s stunning control of the dominating narrative. His engagement and concentration never wavered; he united the drama; and though the melodic range of the narrator’s part is quite narrow he conjured variety and power, mirroring the passions of the text, and differentiating between direct speech and narration. I was transfixed. Tancredi and Clorinda are not able to express their own emotions until the very end. Dahlin’s high tenor line was both fraught with tension and softened by sentiment: a real human appeal, driven by an insistent and compelling anger. The instrumental playing was precise but never rigid - indeed, even quite ‘fey’ at times: the shivering concitato repetitions had real grace, while pizzicato swords clashed brightly and fanfares ‘trumpeted’ in rich triadic pronouncements.

This was a fairly short concert and so we were treated to an encore - though at over ten minutes, Luigi Rossi’s Serenata a tre voci: Amante ‘Rappresentan gl’orrori di questa notte’ might have been more appropriately positioned within the declared programme, which would have at least given us access to the text. It made for a divertingly light, and however well sung and played, not wholly satisfying close to the intense musico-dramatic expression of love and war which had preceded it.

Claire Seymour

Les Talens Lyriques : Christophe Rousset (harpsichord), Eugénie Warnier (soprano), Anders J Dahlin (tenor), Magnus Staveland (tenor)

Claudio Monteverdi - ‘Chiome d’oro’, ‘Quel sguardo sdegnosetto’, ‘O sia tranquillo il mare’ (Settimo libro de madrigali); Giovanni Kapsberger - Libro primo di sinfonie a quattro voci; Monteverdi - ‘Ohimè ch’io cado, ohimè’, ‘Ardo e scoprir’ ‘Lamento d’Arianna’ fromArianna, ‘Sì dolce è’l tormento’, Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda

Wigmore Hall, London; Thursday 21st February 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Staveland-photo-by-Anne-Valeur-01-ed.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Les Talens Lyriques at Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Magnus StavelandPhoto credit: Anne Valeur

February 22, 2019

"It Lives!": Mark Grey 're-animates' Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

They included the gloriously named Humgumption; or, Dr.Frankenstein and the Hobgoblin of Hoxton (1823), Frank-in-Steam; or, The Modern Promise to Pay (1824), and Another Piece of Presumption (1823) in which Peake delivered a burlesque on his own play - one of the first light-hearted treatments of what was to become a cultural icon, and anticipating subsequent humorous explorations of the ‘myth’, such as Mel Brooks’s 1974 film Young Frankenstein, a comedy which itself pays homage to Universal Studios’ Frankenstein films of the 1930s.

When Mary Shelley gave literary life to her now infamous Dr Frankenstein and his progeny-cum-doppelgänger, she surely could not have imagined that her text would take on a life of its own, its offspring during the following 200 years being assembled from a miscellany of bits and parts much like the creature itself. Recently widowed, financially insecure, a single mother, in August 1823 Shelley returned to England hoping for support from her in-laws, only to find that success came from unexpected quarters. On 24 August, she wrote to Leigh Hunt, ‘But lo & behold! I found myself famous! - Frankenstein had prodigious success as a drama & was about to be repeated for the 23rd night at the English opera house’. [1]

The wellspring of dramatic, cinematic and balletic adaptions has seemed infinitely fertile. The first silent screen adaptation came in 1910; James Whale’s 1931 film, which was based on Peggy Webling’s stage version, spawned a ‘Bride of’ and ‘Son of’, cementing the image of Boris Karloff’s creature in the cultural consciousness. The title of Kenneth Branagh’s 1994 film, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, attests to its wish to honour its source with veracity; The Rocky Horror Show gave us the transvestite Dr Frank N. Furter. Nick Dear’s version for the National Theatre (2011) alternated Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller in the roles of creator and created. A female Frankenstein trod the boards in Greyscale and Northern Stage’s 2017 production of Selma Dimitrijevic’s variant on Shelley’s novel, as one Victoria Frankenstein overcame restrictions upon women’s study of science in England by travelling to Bavaria to study chemistry and cadavers. With Doo-Cot Theatre’s Frankenstein - the Final l, which features ‘an 8-foot animated creature [with] live digital imagery and projection, a specially-composed soundtrack and choreography’, Frankenstein firmly entered the technological age.

Mark Grey. Photo credit: Stella Olivier.

Mark Grey. Photo credit: Stella Olivier.

The novel and our response to it have evolved in time, as we develop our own narratives in relation to the original text, explains composer Mark Grey, whose new opera Frankenstein will premiere at La Monnaie in Brussels from 8 - 20 March 2019, directed by Àlex Ollé ( La Fura dels Baus) and conducted by Bassem Akiki.

Shelley’s text, which incorporates contemporary scientific developments such as galvanism and vitalism, is often viewed as a cautionary tale of over-reaching technological endeavour and the failure of science to regulate itself. But the novel’s social and cultural implications are much more complex. Indeed, in conversation with Mark, I suggest that the challenge of creating an opera from a text which bursts and bristles with such wide-ranging themes and debates - the questing Romantic hero, scientific experimentation, social democracy versus the fear of the inchoate revolutionary mob, the innocence of childhood, Gothic horror and terror, patriarchal oppression, male fear of female fertility and procreative power, the blasphemous usurpation of God’s role and the penalties for violating Nature - is a daunting one.

Very aware of the potential traps that are lying in wait for the composer who attempts to adapt a literary text for the operatic stage, Mark explains that the opera that he and his librettist Júlia Canosa i Serra have created does not - indeed, given the complexity of its narrative structure, cannot - tell the novel verbatim. Rather than looking back he has looked forwards, pulling the novel from its literary past and propelling it several centuries into the future. He has aimed both to respect Shelley’s text, and its place in history, and to create a work which is expressive of the day in which we live. After all, he remarks, Shelley’s own novel melded voices and echoes from various texts - Paradise Lost, ‘The Ancient Mariner’, the Prometheus myth - inside a new literary “umbrella”.

Grey describes his aim to make a “visceral connection” with what Mary Shelley was experiencing at the time that she wrote her novel: guilt for the death of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, the vehement advocate for women’s rights who died eleven days after the death of her second daughter; and for the death of her own premature infant; and remorse at not having been more attentive to her half-sister Fanny, whose depression led her to commit suicide.

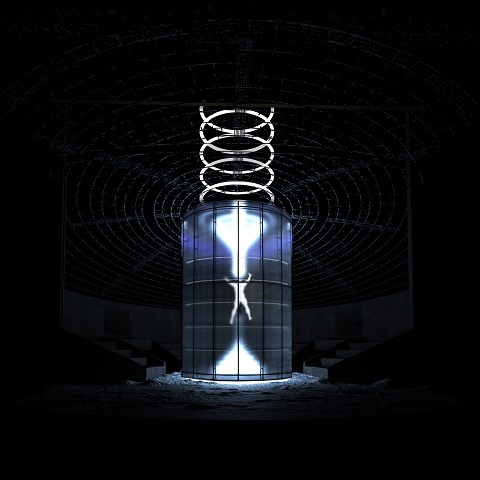

Photo credit: Alfons Flores (La Fura dels Baus).

Photo credit: Alfons Flores (La Fura dels Baus).

I suggest to Mark that this theme - death as an ever-present companion to birth - seems to me to be the heart of the novel. Victor Frankenstein, too, is motherless; what he calls the ‘first misfortune’ of his life, when he mother dies having caught scarlet fever from his cousin Elizabeth, is both the birth of his awareness of the potential of modern science, and ‘an omen, as it were, of my future misery’. Victor comes to fear that, should their union be consummated, his beloved Elizabeth will become pregnant and die. Indeed, the dream which Victor has just after bringing his creature to life is telling: ‘I thought I saw Elizabeth, in the bloom of health, walking in the streets of Ingolstadt. Delighted and surprised, I embraced her, but as I imprinted the first kiss on her lips, they became livid with the hue of death; her features appeared to change, and I thought that I held the corpse of my dead mother in my arms; a shroud enveloped her form, and I saw the grave-worms crawling in the folds of the flannel.’ One is put in mind of a dream that Shelley recorded in her journal on 19 March 1815, shortly after the death of her first child: ‘Dream that my little baby came to life again - that it had only been cold and that we rubbed it before the fire & it lived.’

Mark suggests that patriarchal dominance, too, is also a covert element within Shelley’s story, as well as her ‘difficult’ relationship with her father, William Godwin. Indeed, in the introduction to her novel she notes the Percy Bysshe Shelley was, ‘from the first very anxious that I should prove myself worthy of my parentage’, and years later she recorded in her journal, ‘I was nursed and fed with a love of glory. To be something great and good was the precept given me by my father: Shelley reiterated it’.

. Photo credit: Alfons Flores (La Fura dels Baus).

. Photo credit: Alfons Flores (La Fura dels Baus).

But, many early versions, particularly the Hollywood accounts of the narrative which stamped the powerful visual imagery of Boris Karloff’s creature on our collective consciousness, have in Mark’s words, “stripped out” the tale - whether motivated by the need to entertain, or by time constraints - and it is the desire to retrieve some of what has been “lost” that has influenced Mark’s and Júlia Canosa i Serra’s approach. I wonder whether the narrative structure - a Chinese-box form, with its framing letters from Robert Walton, who meets Victor on the frozen expanse of the Arctic as the latter quests for a vengeful reunion with his creature; the creature’s first-person retrospective account; and sundry inter-woven letters and diary entries - is a prohibitively complicated basis for an opera libretto. Mark is quick to agree - after all, who knows whether Walton hasn’t gone crazy too! - but he explains that he and Canosa i Serra have “unravelled the onion” of the narrative, and given priority to the creature’s narrated memories of its ‘birth’, development, acquisition of language, and of its rejection by those human beings that it encounters, to create a subjective flashback.

. Photo credit: Alfons Flores (La Fura dels Baus).

. Photo credit: Alfons Flores (La Fura dels Baus).

It’s a flashback that is set in the future. Mark reminds me that Walton is the only person other than Victor to see the creature as it heads towards its professed funeral pyre at the North Pole. In Mark’s opera, a team of scientists, re-enacting Walton’s quest, so to speak, find the preserved form of the creature in the granite blocks of ice, and re-animate it. The story thus begins with remembrance of the past.

So much of our response to the creature depends on the rhetorical power of its appeals to its ‘maker’, I suggest: it is less ‘monster’ and more ‘poet’? Does Mark’s musical language attempt to guide us towards a sympathetic, even empathetic response to the creature? Mark’s interest in issues of social justice has been informative here, leading him to emphasise Shelley’s criticism of the social injustices and prejudices of her day. They are, after all, our own, Mark points out: we only have to look at the situation in the US today (and in the UK and Europe, I add), where racial concerns about the ‘Other’ are feeding oppression, suffering and violence. His opera retains the ‘blind man’ of the original: the father of the De Lacey children whose close family bonds, despite their poverty, teach the creature values of kinship, community and compassion. Unaware of the creature’s physical appearance, the blind man appreciates the creature’s care and articulacy, in contrast to even the ‘innocent’ children - like William, Victor’s younger brother - who recoil at its physical ‘ugliness’, which they associate with evil and menace. One thinks of the Syrian refugees trying to relocate into Europe, Mark says, and the way the ‘outcast’ is such a powerful emblem of social prejudice and injustice today.

In addition to his extensive work as a composer - which has included world premieres at famous concert halls including Carnegie Hall and The Walt Disney Concert Hall, and commissions by prestigious organisations including the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra - Mark is also an Emmy award-winning sound designer, having collaborated with composer John Adams and others for over three decades. In 2002 he pioneered the way as the first sound designer in history to design for the New York Philharmonic at Avery Fishery Hall; and, Mark was the artistic collaborator and sound designer for On the Transmigration of Souls by John Adams, which commemorated the lives lost in the World Trade Centre Attack on September 11, and for which Adams won a Pulitzer Prize.

Mark Grey. Photo credit: Stella Olivier.

Mark Grey. Photo credit: Stella Olivier.

Mark sees technology as a way to both draw out the fantastical elements of Shelley’s story, and to make it more ‘believable’. After all, what is ‘reality’ today, he asks? We have AI, robotics, drones that fly themselves and are fighting wars. I guess that I am one of the ‘academics’ whom he describes, with their head and pens down! But, Mark’s ideas about how one might find a way to express the contemporary “balance between creator and created”, something which is perhaps “unknown”, are engaging and intriguing.

As Mark explains, the creature begins life like a child - one rejected by its ‘parent’, who recoils from a gaze which reflects his ‘self’: Victor cringes when ‘his eyes, if eyes they may be called, were fixed on me’. The creature grabs Victor’s notes and begins to assemble words into language, and to comprehend through reading, that he is ‘other’ and ‘outcast’. Mark’s music seeks to communicate this process: initially the vocal writing for the creature is melodramatic, as he hangs on a vowel or employs fluid melisma; but, as he assembles words and pushes then into more formal rhythmic combinations, he becomes more musically articulate, and confident.

I had read that Mark and Júlia Canosa i Serra aimed originally ‘to cast the Creature in as much of an androgynous light as possible, falling somewhere between genders’. Mark explains that the first performance of the opera had been planned for the La Monnaie in 2016, but that structural renovation of the house had resulted in a delay. Originally, they had envisioned the monster as being of ambiguous sexual identity - it is assembled in the novel from ‘bits’ - and had considered casting the creature as an en travesti role. However, further consideration had led them to conclude that this might confuse the story, and so the idea of making the creature a high tenor came to mind. Mark comments that in the novel the creature is fighting for its identity: both its social and sexual identity. It has almost supernatural physical powers of speed and strength, but speaks with eloquence, sensitivity and insight. Mark had worked with Finnish tenor Topi Lehtipuu in the past, and at 6 foot 7 inches or so, and with a slender frame, not to mention a light but strong high tenor voice, he seemed perfect for the role. The opposite, one might think, of Boris Karloff’s lumpen, lurching ‘monster’.

After the Monnaie production, Mark will head to Rome in April for a performance of his Frankenstein Symphony at the Auditorium Parco della Musica, given by the auditorium’s Contemporanea Ensemble and conducted by Tonino Battista. The piece is an exciting collaboration with the National Geographic, who are bringing their Festival of Sciences to Italy’s historic capital with the theme of invention. At the time of the initial postponement of the production, Mark took the opportunity to extract five scenes from the opera and transform these into instrumental form. He explains that it was helpful to hear these orchestral presentations of his work, and to connect musically with the score before it was staged - the difference between musical and theatrical time is something to which he returns during our discussion. It was a luxury to be able to re-examine and re-adjust the score - to “nip-and-tuck” (the scientific metaphor seems apt!) - and to be able to make it more agile in places, not so heavy, he explains. The Frankenstein Symphony is essentially a ‘symphonic suite’, which transfers writing for voice into instrumental form: a complex process of revision and assemblage from diverse parts.

Looking ahead, I ask Mark about his new project, to be presented in April 2020, Birds in the Moon - a travelling chamber opera for two voices and string quartet, which will be staged in a mobile shipping container, exploring themes of migration and immigration. This is a work which really will be ‘brought to the people’: a shipping container will be converted into a ‘magical box’, the sides of which open to form a stage - a sort of “travelling carnival”, Mark suggests. This is a work that he imagines travelling “down South”, to the US border with Mexico, though since it will be ‘housed’ on the back of a truck, it could pretty much roll up anywhere, and the shipping container could serve as a metaphor for industrial sweat shops as much as for deportation compounds.

In the Introduction to Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus Mary Shelley bids her ‘hideous progeny go forth and prosper’. Does she mean the creature? Or, her own text? She speaks, after all, of her ‘affection’ for the latter, ‘for it was the offspring of happy days, when death and grief were but words which found no true echo in my heart. Its several pages speak of many a walk, many a drive, and many a conversation, when I was not alone ...’. The novel embodies Mary Shelley’s struggle to ‘create’. Since its first appearance countless others have sought to re-animate the novel. And, doubtless we all do so in our own image.

Claire Seymour

[1] See John Robbins (2017), ‘“It Lives!”: Frankenstein, Presumption, and the Staging of Romantic Science’, in European Romantic Review, 28:2, 185-201.

Photo credit: Alfons Flores (La Fura dels Baus)

February 21, 2019

Bampton Classical Opera Young Singers' Competition 2019

The previous winners were mezzo-soprano Anna Starushkevych (2013), sopranoGalina Averina (2015) and mezzo-soprano Emma Stannard (2017). In 2017 an Accompanists’ Prize was introduced, and the first winner was Keval Shah. Bampton Classical Opera has a reputation for its commitment to young talent and a number of singers who have appeared on the Bampton stage have gone on to work with national companies such as The Royal Opera, English National Opera and Opera North.

The first round of the Bampton Classical Opera Young Singers’ Competition 2019 (closed sessions) will take place on 5 and 6 October in London. The public final will take place in the Holywell Music Room, Oxford, on Sunday 17 November at 6pm. This is always an entertaining and thrilling event, and a chance to hear some remarkable performances. Judges for the competition include two internationally renowned British singers: tenor Bonaventura Bottone and mezzo-soprano Jean Rigby. Bampton is delighted to announce they are joined this year by the esteemed accompanist and conductor Phillip Thomas, who was a vocal coach and répétiteur at English National Opera, and the official accompanist to the BBC Cardiff Singer of the World for many years.

There will be a fund-raising reception for this year’s Young Singers’ Competition on 26 March at the Caledonian Club, Halkin Street, London SW1 . Bampton Classical Opera is honoured that Benjamin Hulett, one of the first young singers to perform with the Company, who now has an international career at the highest level, will launch this year’s competition, talk about his career and give a short recital. He will also be commemorating his 20th year as a professional performer. Benjamin first performed for the Company in 2000 in Stephen Storace’s Comedy of Errors, which is very apt as this year Bampton is staging Storace’s other Viennese opera Bride and Gloom. Benjamin commented: “ Bampton Classical Opera is a brilliant company who work with a lot of rising stars, often spotting them before anyone else, and their performances are excellent .”

Tickets, including champagne, canapés and a ticket to the November final are £60 and will provide all-important support to the competition. For tickets to the fund-raising reception on 26 March contact Anthony Hall, Administrator, Bampton Classical Opera ( anthony@bamptonopera.org)

Competitors for the Young Singers’ Competition 2019 can apply by downloading an application form and information document from the company’s website - www.bamptonopera.org or on request by emailing ysc@bamptonopera.org. Applications open on 1 March, 2019 and close on 31 July.

First (Closed) Round:

Venue: tbc, London

Date: Saturday 5 and/or Sunday 6 October

Final (Public) Round

:

Venue: Holywell Music Room, Oxford

Date/Time: Sunday 17 November, 6pm

First prize £1,500 - Second prize £600

There will also be a £500 Accompanists’ Prize.

Previous Winners and Runners-up

:

2013

Winner: Anna Starushkevych (mezzo-soprano)

Runner-up: Rosalind Coad (soprano)

2015

Winner: Galina Averina (soprano)

Runner-up: Céline Forrest (soprano)

2017

Winner: Emma Stannard (mezzo-soprano)

Runner-up: Wagner Moreira (tenor)

Accompanists’ Prize: Keval Shah

February 20, 2019

Petrenko Directs Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis

Though Beethoven himself never heard a complete performance of this craggy mass, he considered it his greatest work. In it, he distilled techniques from an exhaustive three-year study of Western religious music since Palestrina, updating them into a style that presages his late symphonic and chamber works. The result is a sprawling work, constructed out of a dense accumulation of disparate fragments in an almost post-modern manner. Joyous exclamations sit cheek by jowl with tender laments, each painted in contrasting colors, timbres and styles.

Given, in addition, the sheer technical challenge and occasional awkwardness of the solo and choral writing, it is hardly surprising that many performers and listeners find the work unapproachable, even baffling. Yet the challenge has long attracted great conductors: most famously, Toscanini and von Karajan, both of whom tended to treat the work like a grand symphony. In recent years, early music experts Gardiner and Harnoncourt have made the case for a contemplative and less overtly romantic interpretation.

From the first note, one hears Petrenko’s debt to the latter tradition. He insists on extreme transparency, tightly controlled balances, restrained dynamics, rhythmic energy and swift tempos – a gentle, other-worldly approach that projects clearly from the stage of the acoustically near-perfect Nationaltheater. At the same time, however, the warmth and polish of modern orchestral instruments accentuates the romantic side, even if at times one might wish for more expressiveness in the phrasing and exuberance in the fugal climaxes. The unique tension in the Angus Dei, for example, in which forlorn pleas for peace echo above an oddly warlike undercurrent, hardly registers. Still, Petrenko’s compromise is surely preferable to the confused bombast or harsh precision this work often elicits.

The orchestra responded brilliantly, following every command – even at some remarkably swift tempos. As a full-time pit band, they naturally command operatic techniques, such as an aura of rapt transparency by attacking chords at the marked dynamic and then having all but the solo parts fall away. The Staatsoper chorus, too, displayed rare subtlety and blend, even if Petrenko’s restraint and Beethoven’s challengingly high vocal lines sometimes pushed the sopranos to the brink.

The difficulty of Beethoven’s choral writing is exceeded by what he gave the four vocal soloists. Petrenko appears to have selected these singers, which includes notable interpreters of Baroque and modernist works, to complement his understated interpretation. Outstanding was the contribution of Marlis Petersen, who approaches the harrowing soprano part with no apparent strain, perfect intonation and – almost uniquely, in my experience – a warm yet focused tone right up to the top of the voice. Young mezzo Olga von der Damerau responded with equal passion and warmth, if slightly less solid technique. Tenor Benjamin Bruns negotiated the punishingly tessitura clearly and sweetly, despite a tendency (at least early on) to approach notes from below. In any other company, young Bass Tareq Nazmi might have seemed underpowered – one did wish for more passion in the Agnus Dei – yet nonetheless projected with precision and feeling.

It added up to as fine a performance of this great work as one is likely to hear these days. The sold-out crowd of Sunday morning spectators remained utterly silent during the work and responded enthusiastically afterwards.

Andrew Moravcsik

Cast and production information:

Marlis Petersen, soprano; Olga von der Damerau, mezzo-soprano; Benjamin Bruns, tenor; Tariq Nazmi, bass. Kirill Petrenko, conductor. Chorus of the Bayerische Staatsoper. Bayerische Staatsoper. Nationaltheater, Munich. 17 February 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kirill_Petrenko.jpg image_description=Kirill Petrenko [Photo by Monika Rittershaus courtesy of Berliner Philharmoniker] product=yes product_title=Petrenko Directs Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis product_by=A review by Andrew Moravcsik product_id=Above: Kirill Petrenko [Photo by Monika Rittershaus courtesy of Berliner Philharmoniker]February 19, 2019

Stéphanie D’Oustrac: Sirènes

D’Oustrac’s Sirènes is also valuable because it demonstrates different approaches to the art of song for voice and piano. Berlioz’s Les Nuits d’été op 7, to poems by Théophile Gautier, initially completed in 1841, was exactly contemporary with the works of Schumann’s Liederjahre. Later, Berlioz would expand the accompaniment for orchestra, effectively creating a new genre, orchestral art song, which would be developed later in the century by composers like Mahler and Hugo Wolf. Nonetheless, even in the original form for voice and piano, these songs are highly individual, quite distinct from the songs of Schumann and Mendelssohn. “I only wish people to know that [these works] exist”, wrote Berlioz, “ that they are not shoddy music . . . and that one must be a consummate musician and singer and pianist to give a faithful rendering of these little compositions, that they have nothing to do with the form and style of Schubert’s songs”.

These mélodies of Berlioz are characterized by elegance and restraint. In “Villanelle”, for example, the repeating patterns in the piano part might evoke Schubert, but there’s an effervescent gaiety in them that is matched by graceful flow of the vocal line. In “Le spectre de la rose”, the more languid pace allows the voice to curve sensuously. Berlioz clearly understood the carnal undertones in Gautier’s poetry. The piano part is gentle, but persistent, like an embrace. When D’Oustrac’s tone deepens with the phrase “Ô toi qui de ma mort fus cause”, one can almost sense the perfume rising from the petals of the doomed rose. Although Les Nuits d’été is not a song cycle in the strictest sense of the term, recurring themes of love, and death and perpetual change give it a coherence which is particularly clear when it is performed with the intimate focus that a single singer and pianist can achieve. The three songs, “Sur les lagunes : Lamento”, “Absence” and “Au cimetière: Clair de lune”, form a unit, sombre with the stillness of the tomb, which is then broken by “L’île inconnue” where the ebullient high spirits of “Villanelle” return. Les Nuits d’été begins with promise of Spring and new life, and ends with adventure. “La voile enfle son aile, La brise va souffler.”, D’Oustrac breathing buoyancy into the word “souffler”. Though Heine inspired Mendelssohn and Schumann with dreams of the East, Gautier and Berlioz are tapping into an even deeper vein in the French aesthetic : ideas of freedom, change and new frontiers in exotic settings. D’Oustrac and Jourdan extend Les Nuits d’été by following it with Berlioz’s La mort d’Ophélie, from Tristia op 18, a setting of a ballade by Ernest Legouvé, who, like Berlioz himself, adapted Shakespeare for French theatre. Ophélie, who dies for love, floats upon a torrent, depicted in the rippling piano part. “Mais cette étrange mélodie passa rapide comme un son”. Though the voice imitates a lament, this is not so much a song of mourning but a transformation through music. The stream carries “la pauvre insensée, Laissant à peine commencée Sa mélodieuse chanson.”

This recording is titled Sirènes, tying Berlioz’s songs together with Richard Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder, both inspired, in part, by women who awoke strong emotions. Sirens, who attract but aren’t necessarily positive, though they generated great art. With full orchestration, the Wesendonck Lieder showcase Wagnerian flamboyance. But, as with Les Nuits d’été , voice and piano versions concentrate focus on a more intimate scale. Even more pertinently, this highlights Wagner’s place in the context of the Lieder of his time, and in relation to Schumann and Franz Liszt. “Der Engel” is gentle, and the dramatic declamation of “Stehe Still !” more human scale. D’Oustrac and Jourdan are particularly impressive in “Im Treibhaus”, the sensitivity of their expression reflecting the intense inwardness that makes Lieder as powerful a genre as opera.

One of the most iconic siren figures of 19th century Romanticism was the Loreley. This recording begins with one of the most beautiful Loreley songs of all, Liszts’s “Die Loreley” S273/2, a setting of Heine’s poem. D’Oustrac’s silvery timbre illuminates the song, accentuating its mystery. She and Jourdan include another other Liszt setting of Heine, “Im Rhein im schönen Strome”, S272/3 and four settings of Goethe, of which “Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh” S306/2 works particularly well with D’Oustrac’s lucid style.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sirenes.jpg image_description=Harmonia Mundi HMM 902621 [CD] product=yes product_title=Sirènes product_by=Stéphanie d’Oustrac, mezzo-soprano; Pascal Jourdan, piano. product_id=Harmonia Mundi HMM 902621 [CD] price= $19.98 product_url=https://amzn.to/2GXZ2ld

Faust in Marseille

It was a difficult evening at the Opéra de Marseille, a fine cast in service of a production from the Opéra Grand Avignon where stage director Nadine Duffaut has staged 14 productions over the years for her husband Raymond Duffaut, Avignon Opera’s guiding light since 1977 when he was appointed general director by his father, the then mayor of Avignon.

Opera in the south of France traditionally has been mired in politics, the complexities of which extend to the complicities of the Provençal opera houses. This 2017 Avignon Faust soon travels from Marseille to Nice for performances in May.

Mme. Duffaut is in fact an able metteur en scène. Her 2016 Opéra Grand Avignon production of Katja Kabanova which I saw at the Opéra de Toulon (45 miles from Avignon) proved her to be a meticulous storyteller, Janacek’s turgid tale of the intricacies of family and business coinciding with Mme. Duffaut’s obsession with detail. The Katja Kabanova unfolded in nothing more than a white box, Janacek’s motivic complexities directly objectified by Mme. Duffaut’s actors.

Such was not the case in this much reviled production as seen just now in Marseille. The simple bel canto like dramatic structure of Gounod’s naive story was amplified into a complex, bizarre nightmare that can only be deciphered by Mme. Duffaut. There were actually two Fausts, the old one and the young one. Siebel was not Gounod’s trouser role, instead he was sung by a crippled tenor. There was historical black and white film footage of Valentin’s war that was most likely the Franco-Algerian war. All this to make Gounod’s Faust real.

Nicole Car as Marguerite, Jean-Françoise Borras as the young Faust

Nicole Car as Marguerite, Jean-Françoise Borras as the young Faust

The chorus however was an abstract mass of masked black and white movement, the Kermesse enlivened by three contortionist acrobats. Marguerite was at first a huge image projected on a full stage scrim, who later became real in a costume that shouted early 1960’s only to become a huge doll (20 feet or so), then to give birth realistically a vista, and finally to become a shaft of light for her salvation.

Mme. Duffaut’s long time collaborator, set designer Emmanuelle Favre provided a huge, architecturally detailed box, with a shadow box within the back wall covered by a painting of Jesus wearing a crown of abundant thorns (Bosch?) behind which the old Faust appeared from time to time (when he wasn’t writhing on the stage floor). There were occasional projections of leaves, branches and flowers. All in all it was not a pretty sight — what you could see of it through the bizarre lighting effected by Philippe Grosperrin.

77 year-old American conductor Lawrence Foster therefore took the opportunity to forgo exploiting the sweetness of Gounod’s trivial sentimentality in search of a deeper, desperate musical response to the nightmare Mme. Duffaut had erected on the stage. What resulted was a strident deconstruction of French Romanticism, revealing an emotionless musical skeleton. If nothing else this approach revealed the Gounod score to be technically daunting, engendering new respect for the often discounted genius of this composer.

Red shoed Nicolas Courjal was the Méphistophélès. This splendid bass reveled in the lighter banter of Gounod’s score, his words tumbling out into the house providing some moments of true delight in this otherwise lugubrious evening. As did vocal meanderings of the beautifully voiced and extremely well sung Faust of tenor Jean-François Borras, far more at home in French than in Italian as Boito’s Faust (Mefistofele) last summer in Orange. Nicole Car’s Marguerite was a vocal extravaganza indeed, but unlike Faust and the devil she did not find character. Étienne Dupuis as well did not find character in his beautifully sung Valentin, though in his case he was musically trounced by the conducting.

Tenor Kévin Amiel was the frustrating Siebel, frustrating because I really needed the mezzo vocal color. The old Faust, Jean-Pierre Furlan gave Faust’s "Rien! En vain j'interroge" in vocal shreds. Marthe, sung by Jeanne-Marie Lévy, sounded mature indeed. Strangely the student Wagner, played by Philippe Ermelier was about 50 years-old.

Bass Nicolas Courjal travels with the production to Nice. Marguerite there will be sung by Nathalie Manfrino of the original Avignon cast. Stefano Secco will be an Italianate Faust. Italian conductor Giuliano Carella (Toulon Opera’s music director) hopefully may provide a starkly different musical atmosphere though the production will remain hopeless.

Nice be warned.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Marguerite: Nicole Car; Marthe: Jeanne-Marie Levy; Faust: Jean-François Borras: Vieux Faust: Jean-Pierre Furlan; Méphistophélès: Nicolas Courjal; Valentin: Étienne Dupuis; Wagner: Philippe Ermelier; Siebel: Kévin Amiel. Orchestre et Chœur de l’Opéra de Marseille. Conductor: Lawrence Foster; Mise en scène: Nadine Duffaut; Décors: Emmanuelle Favre; Costumes: Gérard Audier; Lumières: Philippe Grosperrin. Opera de Marseille, Marseille, France, February 16, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Faust_Marseille2.png

product=yes

product_title=Faust at the Opéra de Marseille

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Nicolas Courjal as Méphistophélès, Mean-Pierre Furlan as the old Faust [all photos copyright Christian Dresse, courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille

February 18, 2019

Down in flames: Les Troyens, Opéra de Paris

Anyone can trot out superficial clichés about so-called modern productions, but it's far more important to understand why a production works, or doesn't. The starting point as always is the opera, and the ideas behind it.