March 31, 2019

Drama Queens and Divas at the ROH: Handel's Berenice

This Berenice, which channels Georgian grotesque humour, spiked with a light peppering of present-day allusions, is thus a welcome breath of fresh air, borne aloft on the wings of uniformly superb dramatic singing in this ROH/London Handel Festival co-production.

Handel’s opera did not, however, have auspicious beginnings when it was first presented in a theatre on the very site of the current day Linbury Theatre. Appearing during the composer’s ill-fated 1736-37 season, when competitive rivalry with the ‘Senesino Opera’ was taking its toll on Handel’s health and hopes, Berenice was the composer’s shortest running production, closing after four performances with Handel reportedly ‘very much indispos’d’ with ‘a Paraletick Disorder, he having at present no Use of his Right Hand’. Apart from a brief outing in Brunswick in 1743, there have since been just a couple of enterprising student productions (at Keele University in 1985, and at Cambridge in 1993) and two recordings: Alan Curtis’s 2010 offering with Il Complesso Barocco, which followed the Brewer Chamber Orchestra’s 2003 recording conducted by Rudolph Palmer.

Setting the opera in Handel’s eighteenth century enables Thomas to present both elegance and effrontery. The powdered periwigs suggest polite graciousness, but the urbanity is tempered by a coarseness - epitomised by rudely rouged cheeks and the way the boisterous, buckled shiny shoes ride rough-shod over the central, dominating velvet banquette - which reminds us that malodorous chamber pots rather than chivalrous manners were the order of the day.

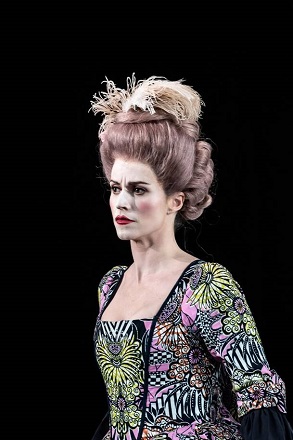

Rachel Lloyd (Selene). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rachel Lloyd (Selene). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Thomas’s decision to transport the opera from Egypt 80BC to the backstage of a Georgian theatre peopled by drama queens and fawning fops is a winning one, suggestive of a political allegory of goings on at Handel’s Royal Academy of Music, whose Covent Garden productions contended with those of the rival Opera of the Nobility at the King’s Theatre. Moreover, Thomas draws upon the tradition of Georgian tragedy which, often lightened by comic contexts, frequently juxtaposed traditional and modern values within strong female figures caught between husband and father, personal desire and public duty: ‘the celebrity actresses playing these women exemplify new individual freedoms as well as their intricate negotiations of a society’s contradictory expectations.’ [1] All well and good for the #MeToo age.

First, the single gripe. Selma Dimitrijevic has provided a new English translation and judging from the few phrases readily audible - “politics is cursed” - it’s a deft text. But, in the resonant Linbury acoustic, consonants went AWOL and, in the absence of surtitles, great swathes of recitative and aria text disappeared into the hinterland. Given the unfamiliarity and complexity of the plot, this was not helpful.

Claire Booth (Berenice), Alessandro Fisher (Fabio), William Berger (Aristobolo), James Laing (Demetrio), Patrick Terry (Arsace), Rachael Lloyd (Selene). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Claire Booth (Berenice), Alessandro Fisher (Fabio), William Berger (Aristobolo), James Laing (Demetrio), Patrick Terry (Arsace), Rachael Lloyd (Selene). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Hannah Clark’s very open set design, for all its focal impact, perhaps does not help. An emerald green, velvet, semi-circular sofa, adorned with a pink fringe, is the sole piece of ‘set’, seeming to extend the seating of the house itself as it stretches across the stage, set within an embracing black expanse. It houses, during the overture, a motley crew of thespians and toffs sipping Earl Grey and engaging in piquant exchanges, its peak crested with a bloomy display worthy of a psychedelic Dutch flower painting. There are a few reminders of the drama’s Egyptian roots - in the brightly hued designs adorning the regal sisters’ pannier hoops, and the two Barbary Lion gates guarding stage left and right.

The plot is a prototype cat’s cradle of romantic knots. Alessandro loves the Egyptian Queen Berenice, who is betrothed to Demetrio Prince of Macedonia - who loves the Queen’s sister Selene - but Berenice, a marital pawn at the hands of the Roman Emperor, is forced into betrothal to Arsace. Baroque amatory quadrangles are here expanded to become a pentagon of possible romantic connections between the Egyptian queen, her sister, and three potential husbands, at the heart of which two feisty and resentful sisters rage, riot and rule.

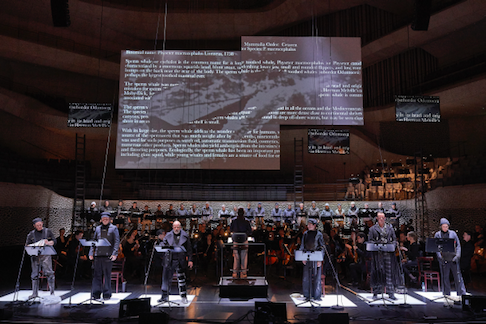

James Laing (Demetrio), Patrick Terry (Arsace) and on-stage continuo. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

James Laing (Demetrio), Patrick Terry (Arsace) and on-stage continuo. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

With the continuo trio of Mark Caudle (cello), Oliver John Ruthve (harpsichord) and Jonas Nordberg (archlute) bewigged and seated amid the action - they have their music snatched from under their noses on occasion - conductor Laurence Cummings was nestled in the Linbury pit with just strings, oboes and bassoon. This was one of Handel’s low-budget orchestrations but, in Cummings’ hands, no less vibrant and buoyant given the scant resources. Tempi seemed just right, and the lean string textures did promote the voices to the fore; that said, Cummings might have drawn greater variety of articulation and tone from the London Handel Orchestra string players.

What really made this such a terrific evening of musical drama, though, was the commitment, engagement and prowess of the superb cast. As the titular monarch, Claire Booth evinced regal righteousness and authority, and a quirky unpredictability, singing with real bite: a little brittle perhaps in her opening rejection of patriarchal command addressed to the Roman ambassador, ‘No, che servire altrui’, though topped with some fantastically acerbic cadential trills, but softened subsequently to convey the Queen’s conflicting emotions. Berenice’s Act 3 ‘Chi t’intende?’ was a tour de force of musico-psychological probing aided by James Eastaway’s delicious oboe obbligato.

Rachel Lloyd flounced furiously as the feisty Selene, dark of tone and temperament, the fioritura fiery but pristine. As Demetrio, loved by both sisters, James Laing sang with unforced strength, flexibility and expressiveness. It was really satisfying, too, to see young members of the cast finding their musico-dramatic feet: Patrick Terry’s Alsace was goofily gormless - we felt for him at the close when he was a loose end as the lovers’ tied the marital knots - though still calmly negotiating the roulades of Alsace’s rage aria, while Alessandro Fisher displayed confidence, professionalism and assurance as Fabio. William Berger was able to summon vocal intensity as Aristobolo.

Best of all, though, was Jette Parker Young Artist Jacquelyn Stucker as Alessandro. The role is less virtuosic than the others, but the pure directness of Stucker’s lyrical spinto surely conveyed the integrity of a man who puts love above self-advancement, and the elegance of the soprano’s stylish phrasing was wonderfully engaging and honest.

The singers balanced a sure sense of Handelian style - and impeccable tuning and passagework - with an individuality of expression which added warmth to what might have been a rather chilly satire. In the concluding ensemble, with the marriages of Alessandro to Berenice and Demetrio to Selene resolving the political and amatory tensions, the soon-to-be-weds sing of the joyous harmony that allows them to set aside the struggles of love and politics. Heart-warming sentiments: if only things were that ‘simple’ in real life.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Berenice

Berenice - Claire Booth, Selene - Rachael Lloyd, Alessandro - Jacquelyn Stucker, Demetrio - James Laing, Arsace - Patrick Terry, Fabio - Alessandro Fisher, Aristobolo - William Berger; Director - Adele Thomas, Conductor - Laurence Cummings, Designer - Hannah Clark, Adaptation - Selma Dimitrijevic, Lighting design - D.M. Wood, Movement director - Emma Woods, London Handel Orchestra.

Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; Friday 29th March 2019.

[1] See The Oxford Handbook of the Georgian Theatre 1737-1832 edited by Julia Swindells and David Francis Taylor.

Photo credit: Clive Barda

March 28, 2019

Martín y Soler: Una cosa rara

First Performance: 17 November 1786, Burgtheater, Vienna.

Principal Characters:

| Queen Isabella | Soprano |

| Don Giovanni (the Prince), her son | Tenor |

| Corrado, a great squire | Tenor |

| Lilla, a shepherdess | Soprano |

| Lubino, a shepherd and beloved of Lilla | Baritone |

| Tita, brother of Lilla | Bass |

| Ghita, beloved of Tita | Soprano |

| Lisargo, chief magistrate | Bass |

Time and Place: 15th Century Spain.

Synopsis:

Act One

As Queen Isabella returns from a hunt, she is met by her son, Don Giovanni. Lilla suddenly bursts into the room, appealing for help from the Queen. She and Lubino are in love. But her brother, Tita, has promised her to Lisargo, the local chief magistrate. The Queen refers the matter to Corrado, much to the chagrin of Don Giovanni who is quite taken with the maid.

Don Giovanni attempts to woo Lilla, but she resists his charms. She confirms her love for Lubino.

As they exit, Tita enters arguing with Ghita. Lisargo follows and interrupts them. Lubino then appears looking for Lilla, whereupon Lisargo departs. Not finding her, Lubino swears vengeance if anything should have happened to Lilla. Lisargo, however, returns with his men to arrest Lubino. Alone, Ghita admonishes Tita to allow the marriage between Lilla and Lubino.

Ghita goes to the Queen's residence where she finds Lilla. They argue but are interrupted by the Queen. She sends Ghita to bring Tita and Lubino. Meanwhile, Corrado tells Lilla of Don Giovanni's love for her. The Prince arrives to renew his courting. Lilla hides when Lubino interrupts them. He asks the Prince for help. The Queen reappears and Lubino repeats his request. Tita and Ghita arrive. The Queen orders Lubino and Lilla to be released. Lilla emerges from her hiding place. To a suspicious Lubino, Corrado attests to the Lilla's loyalty. The Queen orders that there shall be a double marriage of Tita to Ghita and Lubino to Lilla. All are forgiven.

Act Two

While Lubino and Tita are purchasing presents for their betrothed, Ghita tries to convince Lilla to yield to the Prince's courtship. She enumerates the many advantages, including the acquisition of many gifts. Corrado arrives. He too urges Lilla to accept the Prince's advances. Lilla resists these attempts.

The Queen arrives with the Prince. He asks for permission to attend the wedding ceremonies. Lubino and Tita arrives with their gifts, which they present to the Queen. The Queen accepts them and gives them to Lilla and Ghita.

Don Giovanni and Corrado discuss Lilla's refusal to accept the Prince. Lilla and Ghita are looking for Lubino and Tita, who are late. In the darkness, they see two figures whom they believe are Lubino and Tita. They soon discover that they are the Prince and Corrado. Lubino and Tita arrive at that moment, their suspicions aroused.

Later that evening, they vent their suspicions, which are fiercely denounced as baseless. As all doubts are dispelled, the Prince arrives to serenade Lilla. A confrontation ensues. Lisargo comes forward so as not to compromise the Prince. In hiding, the Prince fires his pistol to prevent more of his followers from coming. Lubino and Tita attack Lisargo with the help of Lilla and Ghita. The Prince comes forth to bring peace. Tita angrily walks away, followed by Ghita.

After finding presents given by the Prince, Tita remains suspicious. Tita tries to turn Lubino against Lilla. Lubino, however, remains steadfast. Nonetheless, Tita convinces Lubino to go to the Queen to seek justice. Lubino asks who is trying to seduce his betrothed. The Prince asks Corrado not to reveal the truth. Corrado then steps forward and accepts the blame. The Queen dismisses him and orders him to be sent into exile.

Lilla and Ghita enter and thank the Queen for upholding their honor. The Queen returns to the hunt with all in celebration.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/The_young_shepherdess%2C_by_William-Adolphe_Bouguereau.jpg image_description=Adolphe-William Bouguereau: The Young Shepherdess, 1895 audio=yes first_audio_name=Vicente Martín y Soler: Una cosa rara first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Cosa_rara.m3u product=yes product_title=Vicente Martín y Soler: Una cosa rara product_by=Cinzia Forte, Luigi Petroni, Luca Dordolo, Rachele Stanisci, Yolanda Auyanet, Lorenzo Regazzo, Bruno de Simone, Pietro Vultaggio, Orchestra e Coro del Teatro La Fenice, Giancarlo Andretta (cond.).Live recording, 17 September 1999, Teatro Mancinelli, Orvieto

Boston Lyric Opera's East Coast Premiere of The Handmaid’s Tale

The Handmaid’s Tale opera was written by Danish composer Poul Ruders and librettist Paul Bentley in 2000. Like the book and the hit television adaptation, the story takes place in Gilead, a dystopian society formed by American Christian fundamentalists who assassinate the President and construct a rigid class system for women. The Handmaid’s Tale is anchored by the story of Offred, a woman who rebels against theocratic patriarchal rules through alliances and secretive friendships that she hopes will uncover the fate of her husband and child. Stories of other handmaids, the tyrannical Aunts who run the Rachel and Leah Center, the men who control Gilead, and Offred’s life in “the Time Before” complete the narrative.

“Of all the projects I’ve ever done, this is the one that least needs an explanation of why we are doing it,” said Bogart. “Every once in a while, a piece of literature, a fiction, or a painting becomes so meaningful to a culture that everyone pays attention, and the culture is changed because of it. In theater and in opera we create a democratic space with an audience watching something together that speaks to what’s on the collective mind. The Handmaid’s Tale and the concerns it raises is on everyone’s minds right now.”

Ruders’ score blends folkloric music, a cinematic sound world of hypnotic and ominous repetition, haunting choral singing, moments of minimalism, and duets and trios that break tenets of traditional opera.

The Handmaid’s Tale boasts one of BLO’s largest principal casts in several seasons and includes nearly 40 chorus members. Jennifer Johnson Cano (BLO’s 2015 production of Don Giovanni and 2016’s Carmen) sings the pivotal role of Offred.Caroline Worra (BLO’s 2016 Greek, 2010 Agrippina and 2013 Lizzie Borden) returns as Aunt Lydia. Metropolitan Opera regular Maria Zifchak, in her BLO debut, is Serena Joy. Matthew DiBattista plays The Doctor.David Cushing is the Commander and Michelle Trainor is Ofglen.

Additional performers include Chelsea Basler,Jesse Darden, Felicia Gavilanes,Dana Beth Miller, Kathryn Skemp Moran,Omar Najmi, Vera Savage and Lynn Torgrove.

David Angus conducts the BLO orchestra. Set and costume design is byJames Schuette. Lighting design is by Brian Scott. Adam Thompson does projection and video design. Sound design is by J Jumbelic and movement direction is by Shura Baryshnikov (daughter of Mikhail Baryshnikov and Jessica Lange).

Bogart is Co-Artistic Director of the ensemble-based SITI Company, head of the MFA Directing program at Columbia University, and author of five books. With SITI, Bogart has directed more than 30 works in venues around the world. Her recent operas include Handel’s Alcina, Dvorak’s Dimitrij, Kurt Weill’sLost in the Stars, Verdi’s Macbeth, Bellini’s Norma, and Bizet’s Carmen. Her many awards and fellowships include three honorary doctorates (Cornish School of the Arts, Bard College and Skidmore College), a Duke Artist Fellowship, a United States Artists Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Rockefeller/Bellagio Fellowship, and a Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Residency Fellowship.

The Handmaid’s Tale performances are Sun May 5, 2019 @ 3:00pm; Wed May 8, 2019 @ 7:30pm; Fri May 10, 2019 @ 7:30pm; Sun May 12, 2019 @ 3:00pm.

Tickets to The Handmaid’s Tale are $25-$182, depending on performance and seat location. Tickets are available online at www.blo.org/tickets, by phone at 617-542-6772 (Mon.-Fri, 10 am to 5 pm) or by email at boxoffice@blo.org.

BLO offers a variety of discounts at each performance for students, young professionals, community members and groups of 10 or more. Contact Audience Services at 617.542.6772 or boxoffice@blo.org.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BLO%20HI%20RES%20HANDMAIDS%20TALE%20W%20TITLE%20PHOTO%20Liza%20Voll.jpg image_description=Image by Liza Voll courtesy of Boston Lyric Opera product=yes product_title=Boston Lyric Opera's East Coast Premiere of The Handmaid’s Tale product_by=Press release by Boston Lyric Opera product_id=Above image by Liza Voll courtesy of Boston Lyric OperaMozart’s Mass in C minor at the Royal Festival Hall

That might seem odd, given that he proved himself very much a choral rather than an orchestral conductor, but the concerto came off best precisely because control of its direction was for the most part in the more than capable hands of pianist, Nico de Villiers. There was no doubt whatsoever that he was the real thing, offering playing both pellucid and, where required, weighty (making me keen to hear his Brahms). Insofar as he was able to lead the London Mozart Players, he did, with all the give and take of chamber music. The shaping of the first-movement cadenza offered a conspectus of that movement, even the work, as a whole. A lovely blend of ‘Classical’ and ‘Romantic’ was similarly achieved in the Intermezzo, also benefiting from fine cello playing (though a few more cellos and indeed strings more generally would have been welcome). Finely sprung rhythms characterised a finale both buoyant and directed, the LMP on noticeably better form throughout the concerto than in the choral works by Brahms and Mozart that surrounded it.

First of those was Brahms’s Schicksalslied, or ‘Song of Destiny’. Again, one would ideally have had a larger orchestra, not least given the presence of two very large choruses, the Hackney Singers and Lewisham Choral Society, but there were doubtless financial reasons for that. Ludford-Thomas certainly handled those gigantic, Gurrelieder-like choral forces well here. They offered a pleasing sound and excellent diction, clearly well trained, with convincing dynamic contrasts. The final stanza proved hard driven, though, and the orchestra was largely left to fend for itself - sometimes with more convincing results than others.

The second half of the concert was given over to Mozart’s Mass in C minor. The ‘Kyrie’ offered a largely promising start. Swift, if not unreasonably so, and well balanced - again, given the mismatch in size between choruses and orchestras - it once again offered fine choral singing, and a nice change to hear so many voices in Mozart. Alas, soprano, Elin Manahan Thomas proved parted here and elsewhere, also contributing decidedly peculiar Latin pronunciation and ornamentation. If there was nothing especially insightful to Ludford-Thomas’s conducting of the ‘Gloria’, it enabled the chorus, which was a good part of the point of such a concert. Helen Meyerhoff, in its ‘Laudamus’ section proved a more convincing soloist, a bizarrely fast tempo notwithstanding. Subsequent sections sounded more like rushes to the bus stop than moments of Rococo wonder and suffered from poor blend between soloists. By the time we reached the ‘Qui tollis’, choral intonation left a good deal to be desired. However, the teenor, Peter Davoren had some good moments.

Maybe the novelty of such large choral forces had simply worn off, or maybe they were growing tired: either way, the ‘Credo’ seemed more affected by roughness around the edges than had been the case earlier. The ‘Et incarnatus est’, which should be one of the most wondrous movements in all Mozart’s sacred music, suffered from uneven singing, plain strings, and serious disjuncture in pitch between the two; only the woodwind redeemed it. A plain ‘Sanctus’, lumbering ‘Osanna’ and perfunctory ‘Benedictus’ made for dispiriting listening.

Mark Berry

Brahms: Schicksalslied Op.54; Schumann: Piano Concerto in A minor Op.54; Mozart: Mass in C minor KV 427/417a.

Nico de Villiers (piano), Elin Manahan Thomas, Helen Meyerhoff (sopranos), Peter Davoren (tenor), Philip Tebb (bass), Hackney Singers, Lewisham Choral Society, London Mozart Players/Dan Ludford-Thomas (conductor).

Royal Festival Hall, London, Friday 22 March 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Dan-Ludford-Thomas-websize.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Lewisham Choral Society and the Hackney Singers at the Royal Festival Hall product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: Dan Ludford-ThomasMarch 27, 2019

Samson et Dalila at the Met

Serbian born American theater director Darko Tresnjak envisioned a production with the look of a nickelodean (maybe you put your nickel in and out comes “Mon coeur s’ouvre à ta voix”). Or maybe he was thinking of a slot machine (bet with the odds that the tenor can’t make it to the end). He did like shiny, flowing pale blues and pinks for the intimate scenes within his arched scenic structure, intense reds and metallic blues for the big scenes trusting perhaps that these shapes and colors were enough to tell the story.

What the Met did do right was hire English conductor Mark Elder to expose the magnificence of the Metropolitan Opera orchestra, and to motivate the glories of the Met chorus whose opening scene reeked with overt Baroque-esque, old testament Romantic musical profundities that gave us enormous pleasure.

Anita Rachvelishvili as Dalila

Anita Rachvelishvili as Dalila

The stifling symmetry of Broadway designer Alexander Dodge’s scenic structure placed the singers squarely center stage for their big numbers where the artists of the evening did their best to measure up to the symphonic magnificence rising from the pit. Georgian mezzo soprano Anita Rachvelishvili well held her own in powerful voice though I missed a warmth of sensual phrasing in her two famous second act arias. A well-known Carmen Mme. Rachvelishvili did find plenty of fire in her confrontations with Samson and the High Priest.

Lithuanian tenor Kristian Benedikt, who last fall was called upon to finish the opera when tenor Roberto Alagna gave up after the second act, was the Samson at this performance (his only full performance in this 2018/19 run). Mr. Benedikt did make it all the way to the end, though he encountered some rough patches in the second act. Both his first and third act arias were beautifully rendered, his fine tenor holding strong tone to their conclusions. However in the second act and the final scene of the opera his persona and voice were swallowed into the grander trappings of the staging.

The High Priest of Dagon was sung in all thirteen performances by bass-baritone Laurent Naouri in easily distinguishable French though his delivery did not rise to the musical elegance of Saint-Saëns' score and Mo. Elder’s conducting. Note also that the back-of-seat “super” titles (very hard to see) were offered in German and Spanish. Why not French, as it is, after all, the language of the opera?

Male dancers of the corps de ballet

Male dancers of the corps de ballet

Besides the splendid second act arias the famed part of Saint-Saëns' masterwork is the third act orgy that culminates in the destruction of the pagan temple. Ten almost naked ballerinos and eight ballerinas executed a complex choreography conceived by Austin McCormick, artistic director of Brooklyn’s Company XIV. The unballetic style was Martha Graham avant gardesque, a look that flowed uneasily with the grander formal structures of the Saint-Saëns' score.

Despite the thunderous percussion climax the short circuit electric flash within Mr. Tresnjak's nickelodeon did not satisfy as Samson’s crowning moment of superhuman strength. Mr. Tresnjak’s staged oratorio setting of Saint-Saëns' score would have profited from some operatic context.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Dalila: Anita Rachvelishvili; Samson: Kristian Benedikt; Abimélech: Tomasz Konieczny; High Priest of Dagon: Laurent Naouri; First Philistine: Eduardo Valdes; Secon Philistine: Jeongcheol Cha; A Philistine Messenger: Scott Scully; An Old Hebrew: Günther Groissböck. Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera. Conductor: Mark Elder; Production: Darko Tresnjak; Set Designer: Alexander Dodge; Costumes Designer: Linda Cho; Lighting Designer: Donald Holder; Choreographer: Austin McCormick. Metropolitan Opera, New York, March 28, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Samson_Met4.png

product=yes

product_title=Sanson et Dalila at the Metropolitan Opera

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Temple to the god Dagon, with Samson [All photos copyright Ken Howard / Met Opera.

The Enchantresse and Dido and Aeneas

in Lyon

Of rich theatrical interest are the two new productions — Hungarian stage director David Marton’s Dido and Aeneas filtered though Berlin’s late, lamented Volksbühne, and Moscow-formed Ukrainian stage director and theatre theorist Andriy Zholdak’s The Enchantress filtered through the filmic lens of the 1950’s and 60’s (Fellini, Bergman). Of less interest but still of enormous pleasure was Monteverdi’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse, revived in the 1999 William Kentridge South African life-size puppet theater production, sung by members of the Opéra de Lyon young artist program.

Andriy Zholdak’s staging of Tchaikowsky’s The Enchantress is nothing less than monumental. The Enchantress is the ninth of Tchaikovsky’s eleven operas (Eugene Onegin is the fifth, Mazeppa the seventh, Pique-Dame and Iolanta the tenth and eleventh respectively). It is Tchaikovsky’s lengthiest work (just under four hours with one intermission) that only recently is finding its way into the repertory after a tepid reception back in 1887.

Mr. Zholdak makes a strong case that The Enchantress is one of opera’s great theatrical moments, or maybe it was conductor Daniele Rustioni who made the case. Working together the two artists kept their audience spellbound for the duration, the orchestra unflaggingly sustaining the unrelenting tension on the stage.

A bedroom juxtaposed to Prince's dining room, with faces of two adolescent girls seated center back watching action, video projected.

A bedroom juxtaposed to Prince's dining room, with faces of two adolescent girls seated center back watching action, video projected.

A priest, probably a surrogate Mr. Zholdak, extinguished candles in Lyon’s St. John the Baptist cathedral, climbed into a limousine to arrive at Lyon’s Opéra Nouvel (we watched this on video). Arriving onto the stage he contemplated a game of chess, a game that soon moved to the beautiful Nastasia’s humble inn where he engaged her in a game. Four hours later, a few chess boards and a card game later dressed in a green suit he batted tennis balls against the inn’s walls during the wrenching lament of the opera’s antagonist (who had just murdered his own son).

Early on the priest planted a camera in the eye of crucified Jesus then donned virtual reality goggles to watch and encourage things to go from bad to worse. The Prince’s son stopped by the inn briefly. At the mere sight of him Nastasia fell in love. The Prince stopped by a few minutes later and fell madly in love with Nastasia. Neither the Prince’s wife nor the Prince’s son could abide the Prince’s infatuation with Nastasia.

Like in a dream seemingly random images flowed hour after hour alongside, though of course they were related somehow. Location somehow shifted between Nastasia’s mean little wooden inn, the Prince’s towering, blinding white dining room, Nastasia’s boudoir, and a stone chapel with a huge, crucified Jesus. A catalogue of sexual desires were fulfilled, fantasy murders were enacted. A story was somehow told (the Prince’s wife poisons Nastasia, the son renounces his mother, the prince murders his son in a fit of jealous rage).

Tchaikovsky’s score turged on, magnificent arias, magnificent rages, ecstatic duets, huge choral climaxes (though we never actually saw the chorus). Alternative Images flowed unbound, uncontrolled by linear narrative. Zholdak’s world unfolded in an unparalleled display of theatrical craftsmanship, both artistic and technical. Tchaikovsky’s orchestral world spewed forth in unbridled emotion like no Tchaikovsky score you have heard before.

Three (of four) constantly moving scenic elements, crucified Jesus in white light.

Three (of four) constantly moving scenic elements, crucified Jesus in white light.

The Opéra de Lyon assembled an exemplary cast. Beautiful Russian soprano Elena Guseva inhabited the temptress role to perfection in beautiful, warmly Russian tone that never faltered through the punishing several hours of singing. Former Los Angeles Opera young artist, Russian tenor Migran Agadzhanyan gamely played with his teddy bear, soundly berated his mother and ardently declared his love for Nastasia in a total performance. Russian mezzo soprano Ksenia Vyaznikova was unrelentingly terrifying as the mother in music that explored the full mezzo vocal and histrionic range. Azerbaijan baritone Evez Abdulla reveled in splendidly baritonal self indulgent swagger as first the love sick prince then the tortured father.

Polish bass Piotr Micinski played the priest Mamyrov in an amazing display of body language and dramatic concentration in his constant, silent presence as the star of Zholdak’s and now Tchaikovsky’s dream. It was a performance of absolute virtuosity. Of note also was the physicality of the sorcerer Koudma sung by Siberian baritone Sergey Kaydlov. The myriad of secondary roles were sung in fearsome Russian both by Russian singers and by the French artists who appear regularly at the Opéra de Lyon.

Henry Purcell’s masterpiece Dido and Aeneas is of sufficient dramatic magnitude to command an evening in and of itself. However its brief, fifty minute duration does not fill an evening at the opera. It is an unsolvable problem.

Dido and Aeneas with chorus members.

Dido and Aeneas with chorus members.

The Opéra de Lyon offered just now a novel solution — the immersion of Dido’s tragedy and Aeneas’ destiny into a larger piece of conceptual theater. Such theatrical exercise has had impressive precedent at Berlin’s Volksbühne with works like famed director Frank Castorf's dismembering of Dostoyevsky’s Insulted and Humiliated in a seven hour sitting, and Schumann’s setting of Goethe’s Faust Book II ignored in a seven hour sitting because the director decided he didn’t know what to do with it so they would simply stage something or the other on the set built for the opera, never mind that the actors had learned to sing its lines.

Volksbühne formed Hungarian stage director David Marton and his dramaturg Johanna Kobusch knew exactly what to do with Dido and Aeneas to make it into a two hour evening — they sank it into an archeological dig, building on the current scientific myth that time moves in circles. Thus you are where you have already been revealing the multiple civilizations present in Purcell's Dido and Aeneas.

Juno and Jupiter (lower left) video projected (note presence of videographer).

Juno and Jupiter (lower left) video projected (note presence of videographer).

Cleverly Mr. Marton turned to Virgil to find lines for toga-attired Jupiter and Juno to speak while they dug in a covered dig finding artifacts of our tech age. Finnish composer Kalle Kalima created convincing noises and some fine new music from time to time to make much of the spoken episodes into a melodramma of sorts (speech with music). These spoken episodes related the adventures of Aeneas, amplifying the evening beyond the personal tragedy of the queen of Carthage to encompass a larger vision of humanity. Aeneas himself, sung by Guillaume Andrieux revealed himself not only a fine singer but also a high-style actor.

Purcell’s little tragedy did find its way into the melée from time to time, Belinda, sung by a matronly Claron McFaddon, offering sage advice over drinks to Dido, sung by soprano Alix le Saux, dressed for cocktails. A huge black period dress was provided to Mlle. le Saux for Dido’s, "When I am laid, am laid in earth," though this did not manage to support the lament which had little of the wrenching gravity that makes this aria one of opera's towering masterpieces.

There was a striking Volksbühne moment. The face of Icelandic actor, Thorbjörn Björnsson (a former Volksbühne actor), was painstakingly revealed as the dirt covering it (he was fully buried in the dirt of the excavation) was slowly brushed away by Juno (we watched this procedure on video close-up).

Face of buried Jupiter becoming apparent, brushed by Juno, video projected from excavation pit.

Face of buried Jupiter becoming apparent, brushed by Juno, video projected from excavation pit.

Swiss performance artist Erika Stucky (born in San Francisco) made all sorts of vocal noises pinch-hitting as Purcell’s witch plus scrunching cellophane, dragging a shovel, etc. These added bits of performance art were annoying to some of us. Many in the audience had had enough and exited the theater during her bits.

Of particular pleasure were Purcell’s madrigals, gracefully performed by members of the Opéra de Lyon chorus. These highly skilled singers articulated Purcell’s voice lines in ways that added a textural lightness through which new layers of meaning emerged. A sizable string orchestra comprised of members of the Opéra de Lyon orchestra gave a bright sound to what little Purcell we actually heard, as well as to the added intermezzos and their musical destruction by composer Kalle Kalima (dressed in a white suit, he sat with his electric guitar on a high platform in the orchestra pit). Conductor Pierre Bleuse obliged with all the necessary moods.

The production had the feel of a clique of artists who got together to do something they thought was cool. The audience at the performance I attended had little patience for it.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

The Enchantresse Princesse Eupraxie Romanovna: Ksenia Vyaznikova; Mamyrov: Piotr Micinski; Prince Youri: Migran Agadzhanyan; Nenila, sa sœur: Mairam Sokolova; Ivan Jouran: Oleg Budaratskiy; Nastassia (surnommée Kouma): Elena Guseva; Loukach: Christophe Poncet de Solages; Kitchiga: Evgeny Solodovnikov; Païssi: Vasily Efimov; Koudma: Sergey Kaydalov; Foka: Simon Mechlinski; Polia: Clémence Poussin; Balakine: Daniel Kluge; Potap: Roman Hoza; Invité: Tigran Guiragosyan. Orchestre et Chœurs de l’Opéra de Lyon. Conductor: Daniele Rustioni; Mise en scène et décors: Andriy Zholdak; Lumières: Andriy Zholdak et les équipe lumières de l'Opéra de Lyon; Décors: Daniel Zholdak; Costumes: Simon Machabeli; Vidéo: Étienne Guiol. Opéra Nouvel, Lyon, France, March 24, 2019.

Dido and Aeneas Didon: Alix Le Saux; Enée: Guillaume Andrieux; Belinda: Claron McFadden; Esprit / chant / interludes: Erika Stucky; Juno / comédienne: Marie Goyette; Jupiter / comédien: Thorbjörn Björnsson. Orchestre et Chœurs de l’Opéra de Lyon. Conductor: Pierre Bleuse: Concept et mise en scène: David Marton; Composer: Kalle Kalima; Décors: Christian Friedländer; Costumes: Pola Kardum; Lumières: Henning Streck; Vidéo: Adrien Lamande; Dramaturgie: Johanna Kobusch. Opéra Nouvel, Lyon, France, March 23, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Enchantress_Lyon1.png

product=yes

product_title=The Enchantresse and Dido and Aeneas in Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Migran Agadzhanyan as the Prince's son, Elena Guseva as the Enchantresse [photo copyright Stolteth, all photos courtesy of the Opéra de Lyon]

March 26, 2019

The devil shares the good tunes: Chelsea Opera Group's Mefistofele

Arrigo Boito’s preface to his libretto for Mefistofele attests to the writer-composer’s own curiosity about the man who renounces a world, which nevertheless enthrals and ensnares him, as he trives to manipulate the cosmos and transcend human science and knowledge in search of a higher truth. Boito’s examples of Faustian figures include Adam, Solomon, Prometheus, Manfred and Don Quixote, and his own creations - Iago for Verdi’s Otello, Barnaba for Ponchielli’s La Gioconda, and Nerone for the opera which he laboured over for four decades but left unfinished at his death in 1918 - are evidence of his repeated revisiting of the conception of good and evil.

Opera companies in the UK have been more reluctant to revisit Boito’s own Mefistofele, however. Twenty years have passed since ROH’s 1998 semi-staged performance with Samuel Ramey taking the role of the eponymous fiend, and ENO’s production the following year in which Alastair Miles stepped into the devil’s shoes.

What accounts for this reluctance? The opera is intellectually and musically ambitious in range. Boito attempted to create an operatic embodiment of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s drama in its entirety, rather than, as Gounod essayed in his more famous version, just a part of the literary masterpiece. But, Boito’s first efforts met with derision: the opera in five acts framed by a prologue and epilogue which was premiered in Milan in 1868 was a failure and Boito subsequently made several revisions of the work, reducing it to four acts and excising episodes such as a scene at the Emperor’s court and an orchestral Battle Symphony. The terrain traversed is still expansive and diverse, however, encompassing a Frankfurt Square, Faust’s study, the garden of Margherita’s friend Marta, the Brocken valley in the rugged Harz mountains, a prison cell, the banks of the river Peneios - even the firmament itself. One imagines that the scene-changes required in a staged performance might result in an episodic quality.

Then, it’s probably fair to say that Boito’s creative talents were more literary than musical; indeed, some critics have accused Boito of having composed ‘a fabulously tasteless score [that] comes at you like a parody of every operatic cliché’. Moreover, a successful production requires four principal singers of considerable vocal heft and a chorus who can get negotiate tricky fugal challenges and get their tongues around some Italian patter. But, there are some glorious musical effects, terrific arias for the soloists, exciting choral writing and a strong narrative arc. As Chelsea Opera Group confirmed in this superb concert performance at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, Mefistofele does not deserve its neglect.

That this was such a compelling account was in large part due to the sustained dramatic engagement and musical commitment of the entire cast, who through their superb vocal acting turned the alleged ‘clichés’ into tours de force.

Elizabeth Llewellyn (Margherita/Elena). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Elizabeth Llewellyn (Margherita/Elena). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

We don’t see enough of soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn on British stages. A few years ago, she was a familiar face at ENO (where she sang Mimì, Mozart’s Countess Countess , The Magic Flute’s First Lady and Micäela ), and at Opera Holland Park (Countess and Fiordiligi). But, apart from a return to OHP in 2017 to sing Puccini’s Magda de Civry , Llewellyn has found herself more frequently treading the boards of European opera houses - including at Theater Magdeburg and Royal Danish Opera - and made her US debut last year in Seattle’s Porgy and Bess . When I first heard Llewellyn sing, in ENO’s 2010 La boh ème, I admired her ‘warm, generous voice [which] easily reached the rafters of the Coliseum’, and the warmth and generosity of her lyric spinto have only blossomed more richly during the intervening years. She commanded the attention of all in the Queen Elizabeth Hall during the Act 3 prison scene, her soprano falling with a slight duskiness and rising with a rapturous sheen, the projection easy and the phrasing beguiling. If the drama of ‘L’altra notte’ was well-crafted, in the great love duet, ‘Lontano, lontano’, she spun an exquisite, gentle pianissimo; and, when she prayed to God for salvation and rejecting Faust, her dying phrases conveyed every drop of emotional intensity. The spontaneous applause that greeted ‘L’altra notte’ seemed to take Llewellyn a little by surprise, just as she had astonished those in the Hall with such powerful expressivity - an expressively which was equally captivating when she assumed the persona of Helen of Troy in the following Act.

Pablo Bemsch proved an equally impressive Faust. The Argentinian tenor has a lovely sweet sound, fresh and honest, one that is well-supported and consistent. The role is a long sing and Bemsch had the necessary stamina, if not always quite enough heft to top the COG Orchestra and Chorus in the more extravagant tutti outbursts: perhaps it was sensible not to attempt to do battle with the masses, but occasionally Bemsch’s middle- and lower-voice line seemed to slip away - particularly in Act 4 Scene 1 - into the ensemble texture. That said, this was a Faust with whom one could readily empathise. Bemsch communicated Faust’s ardour, yearning and obsessive curiosity, but also his dignity, and there was a strong sense of the passing of time and his growing distress in old age. This was a contemplative, at times introspective Faust, and Bemsch made his reveries ‘real’, particularly in ‘Giunto sul passo estremo’ when the older Faust’s dreams of universal serenity pulsed with elation.

With a dark glint in his eye, an unflinching stare, a mocking sneer twitching his lip and an authoritative physical poise, Armenian-German bass Vazgen Gazaryan was a captivating Mefistofele. He had no problem negotiating the devil’s rather faltering, repetitive melodic lines, firing the short phrases with power, pace and accuracy. Gazaryan’s firm, focused tone had a terrific ‘edge’, by turns dismissive and aggressive, and he demonstrate an assured rhythmic sense. This Mefistofele exuded unabashed conceit when challenging God in the ‘Prologue in Heaven’ but alongside brazen defiance, Gazaryan also suggested the fiend’s frustration. This was commanding dramatic singing, made more gripping by Gazaryan’s consummate knowledge of the role which he sang entirely off-score.

Chelsea Opera Group perform Mefistofele at the QEH. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Chelsea Opera Group perform Mefistofele at the QEH. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Aaron Godfrey-Mayes displayed a bright tenor as Faust’s pupil Wagner and as Nereo in Act 4; Angharad Lyddon was similarly appealing as Marta and Pantalis. The ensembles were persuasively cohesive, and there was plenty of dramatic communication between the principals.

The COG Chorus were kept busy and proved themselves up to the challenges that Boito poses. The blazing vigour of the full choral sound was impressive, though the women were less confident than the men and occasionally less secure in intonation. There was assured and consistent playing, too, from the COG Orchestra. The brass and percussion relished the explosive writing in the Prelude and Epilogue, and woodwind solos and pairings sang with shapeliness. If the fiddles didn’t quite summon a luxuriant sheen, then the string tone was well-blended and the ensemble good, with the inner voices coming through strongly.

Matthew Scott Rogers displayed a good sense of the dramatic shape of the opera. Tempi were bracing but persuasive: only in the Sabbath episode did he seem to leave a few of the chorus and orchestra trailing in his wake! He whipped up musical storms with economical gesture and means. Perhaps a little more gradation of volume would have been welcome - when it was loud, it was loud - but overall the performance had a compelling sweep.

Chelsea Opera Group should be congratulated and thanked for showing us that Boito’s devil has some of the good tunes, but not all of them: there are copious melodic and dramatic riches in Mefistofele and it would be good to hear them again in the opera house soon.

Claire Seymour

Boito: Mefistofele

Mefistofele - Vazgen Gazaryan, Faust - Pablo Bemsch, Margherita/Elena - Elizabeth Llewellyn, Wagner/Nereo - Aaron Godfrey-Mayes, Marta/Pantalis - Angharad Lyddon; Conductor - Matthew Scott Rogers, Chelsea Opera Group Orchestra and Chorus.

Queen Elizabeth Hall, Southbank Centre, London; Sunday 24th March 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Vazgen%20Gazaryan%20as%20Mefistofele.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Boito’s Mefistofele: Chelsea Opera Group at the Queen Elizabeth Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Vazgen Gazaryan (Mefistofele)Photo credit: Robert Workman

March 24, 2019

La forza del destino at Covent Garden

The Royal Opera House’s new production of La forza del destino, directed by Christof Loy and first seen at Dutch National Opera in 2017, had been hyped to the heights since the first moment it was announced that it would reunite Anna Netrebko and Jonas Kaufmann for the first time at Covent Garden since the soprano and tenor formed a triumphant threesome with the late Dmitri Hvorostovsky in La traviata in 2008. The anticipatory buzz was amplified by gossip about tickets changing hand for crazy figures on re-sale sites, speculation about which star would cancel first, and rumours that Kaufmann had been a rare figure at rehearsals, with Azerbaijani tenor Yusif Eyvazov - Netrebko’s husband, who shares the role of Don Alvaro - filling in at the dress rehearsal.

For once, though, a hyperbolic build-up did not culminate with bathos but with brilliance: consummately expressive singing which quite simply entranced and exhilarated. There is never any doubting the luxurious beauty and intense communicativeness of Anna Netrebko’s soprano but on occasion, as in last year’s Macbeth , I have longed for a little more precision to accompany the vocal glamour and shimmer. Here, however, making her role debut as Leonora, Netrebko had me transfixed with a performance in which drama was balanced by discipline, and interpretation was fired by intellect and intuitive insight in equal measure, casting a compelling vocal spell.

Anna Netrebko (Leonora), Jonas Kaufmann (Don Alvaro). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Anna Netrebko (Leonora), Jonas Kaufmann (Don Alvaro). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

From the first gestures of the dumb-show presented during the overture, Loy places Leonora at the centre of the drama and Netrebko’s vocal and physical definition of character was riveting. Though this Leonora was painfully wracked by conflicting desires and duties in ‘Me pellegrina ed orfana’, her Act 1 duet with Alvaro had an almost fierce directness. ‘Madre, pietosa Vergine’ began with a deep darkness, blossomed sweetly, then floated bewitchingly - an exquisitely elegant mezza voce - in ‘Vergine degli angeli’. Nebtrenko rose effortlessly above the orchestra’s throbbing climaxes, while the agonising intensity of ‘Pace, pace, mio Dio’ conveyed both Leonora’s fervour and her frailty with spellbinding magnetism.

Jonas Kaufmann (Don Alvaro). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Jonas Kaufmann (Don Alvaro). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Sweeping in through a window stage-right, as if to counter any doubts about his participation with a bold physical statement of his presence, Kaufmann was a heroic Alvaro, a little restrained at the start but expanding to encompass a magnificent range, vocally and dramatically. The tenor spins a heart-meltingly lovely line, by turns ardent and tender, the lyricism charged with tragic suffering, and, as demonstrated in Act 3’s ‘La vita e inferno’, has absolute control of his voice from the most impassioned fortissimo to the softest whisper, magically grading the diminuendo at the close. Ludovic Tézier’s Carlo was no less impressive, his glowing baritone equally commanding and absorbing as he unleashed a vengeful fury which was countered by smooth lyricism in ‘Urna fatale’; the extended duets of Act 3 - in which Kaufmann and Tézier reprised a partnership first formed in Munich in 2014 - were finely wrought dramatically and musically, and utterly compelling.

Jonas Kaufmann (Don Alvaro), Ludovic Tézier (Don Carlo). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Jonas Kaufmann (Don Alvaro), Ludovic Tézier (Don Carlo). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

And, the casting luxuries did not stop there, with several singers reprising roles that they sang in Holland including American soprano Roberta Alexander who was a splendid Curra, strongly defined and impactful, and Italian tenor Carlo Bosi as the pedlar Trabuco who arrived to sell his wares with a chutzpah worthy of a Dulcamare. Ferruccio Furlanetto’s Padre Guardiano was a growling dark foil to Leonora’s sweetness, while Alessandro Corbelli was excellent as Melitone, fun but never flippant, the text clearly enunciated and gracefully phrased. It’s a shame that the Marquis of Calatrava’s death, which triggers the fateful tragedy, prevented us hearing more of Robert Lloyd’s bass which conveyed a father’s love and his demand for submission with equal conviction. And, it was good to hear Jette Parker Young Artists, Michael Mofidian, as Alcalde. Veronica Simeoni, making her ROH debut, seemed not entirely comfortable in the role of Preziosilla: though she did her best to make ‘Al suon del tamburo’ a rousing romp and danced gamely in the Rataplan chorus, sporting emerald belly-dancer pantaloons and surrounded by somersaulting acrobats in spangly top hats, she struggled to project and to reach the upper echelons of the role securely and confidently.

Anna Netrebko (Leonora), Robert Lloyd (Marquis de Calatrava). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Anna Netrebko (Leonora), Robert Lloyd (Marquis de Calatrava). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

From the pit, Sir Antonio Pappano immediately ratcheted up the tragic intensity in a surging, heated overture, and crafted the ebbs and flows of the tragedy with consummate command. Whether carousing, warring or in devotional mood, the ROH Chorus were in fine voice and entered into the spirit of the lively, sometimes rather inconsequential, tableaux and crowd scenes.

Verdi abandoned the classical unity of time, place and action in La forza, thereby creating a headache for directors who must make varied locations spanning vast geographical distances, and visited over a period of many years, cohere. Then, there’s the problem of how to assimilate the broad humour within the prevailing tragic narrative. Rather than imposing a binding ‘concept’, Christof Loy and designer Christian Schmidt seem to embrace the disunity. The white marble walls of the Calatrava home that we visit in Act 1, subsequently fall though remnants of the mansion remain in the ensuing locales as the stage becomes a palimpsest of places and periods. Costumes allude to diverse epochs and sometimes seem designed to add to the ambiguity and inconsistency.

There are just two assertive directorial gestures, the first being an extended dumbshow during the overture. Here, atop and around the long table which slices across the floor of the Calatrava palazzo, the three main characters are seen as children. As the screen rises and falls three times, destiny plants the dart which will find its target many decades later; Leonora sits, head bowed, beside a small stature of the Virgin Mary which, enlarged and aloft, will cast a deep shadow over her life. Then, as the drama unfolds, Loy offers us recurring projections which zoom in on Leonora at the moment of her father’s accidental death; the moment which thus seals her fate. But, these ‘psychological close-ups’ are distracting and unnecessary: Verdi’s music tells us all we need to know - especially as here, when it is sung and played with such power and impact.

These directorial diversions don’t really matter, though, as the singing is so absorbing. Verdi may keep his hero and heroine apart for much of the opera, as we traverse through taverns, monasteries and war zones, but when Netrebko and Kaufmann are finally united in Act 4 it certainly feels like - if not ‘fate’ exactly - then very good fortune indeed.

Claire Seymour

Verdi: La forza del destino

Leonora - Anna Netrebko, Don Alvaro - Jonas Kaufmann, Don Carlo di Vargas - Ludovic Tézier, Padre Guardiano - Ferruccio Furlanetto, Fra Melitone - Alessandro Corbelli, Preziosilla - Veronica Simeoni, Marquis of Calatrava - Robert Lloyd, Curra - Roberta Alexander, Alcalde - Michael Mofidian, Maestro Trabuco - Carlo Bosi; Original director - Christof Loy, Associate director - Georg Zlabinger, Conductor - Antonio Pappano, Designer - Christian Schmidt, Associate set designer - Federico Pacher, Lighting designer - Olaf Winter, Choreographer - Otto Pichler, Associate choreographer - Johannes Stepanek, Dramaturg - Klaus Bertisch, Royal Opera Chorus (Chorus Master - William Spaulding), Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House Covent Garden, London; Thursday 21st March 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/La%20forza%20ROH%20title%20image.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=La forza del destino, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Jonas Kaufmann (Don Alvaro) and Anna Netrebko (Leonora)Photo credit: Bill Cooper

March 21, 2019

Barbara Hannigan sings Berg and Gershwin at the Barbican Hall

She was singing songs by Berg and Webern with Pierre Boulez and immediately made a great impression. Since then, she has been one of those artists I should make an extra effort to hear; not once have I been even slightly disappointed. Hannigan is, of course, most widely known as a singer, but she has been building a parallel, or rather complementary, career as a conductor in the meantime too. I heard her conduct the Britten Sinfonia in 2013, in works by Mozart, Stravinsky, and Haydn , for some of which she sang too - and once again proved enthusiastic. This concert, her LSO debut, offered a worthy successor in that line, now performing works by Ligeti, Haydn again, Berg, and Gershwin.

Ligeti’s Concert Românesc is one of those pieces we hear more than we probably ought: not in the sense that there is anything wrong with them, but rather that they seem to offer an early, unrepresentative piece by a composer who might otherwise be ignored. Webern’s Passacaglia or even Im Sommerwind would be obvious examples, even Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht. Hannigan is certainly not one to neglect Ligeti; one of her most celebrated performances, not least on YouTube, is of his Mysteries of the Macabre (also with the LSO). I could not help, however, but feel that this was a performance-in-progress - although it may simply have been a matter of nerves, of having come first in the programme. Even when it lacked ‘traditional’ incisiveness, as in the first section, there were gains, though, not least a sense of how close the music might sound to early Bartók, even to Strauss. Bartókian ‘night music’ of a later vintage certainly sang forth in the third section, even if the final ‘Presto’ came off somewhat hard-driven. In any case, there was much to relish from the solo work of LSO principals.

Haydn’s Symphony no.86 furthered Hanningan’s growing reputation in Haydn’s music: always a fine indicator of other strengths. The first movement’s introduction offered a grandeur and expectation that Colin Davis (thinking of the LSO) would surely have appreciated, with none of the irritations that, alas, often accompany Simon Rattle’s way with this composer. If its principal tempo were on the fast side, it was not unreasonably so. The music largely spoke here ‘for itself’, however much of an illusion that may be, the development especially well handled, the final coda a joy. Constructivism and lyricism were kept in a fruitful, generative relationship throughout in the second movement, founded, as it must be, in harmony and harmonic movement. This is music to rival Schoenberg in complexity - something most ‘period’ voices, alas, seem entirely to ignore. So too is the minuet - as soon as one listens, which Hannigan ensured that we did. Its trio relaxed harmonically and offered in tandem a winning sense of relative metrical freedom. Delightful, then, as was the finale, one of my very favourites: heard as if Leonard Bernstein had returned, albeit with greater dynamic variegation. It was as witty as it was thrilling, as convincing vertically as horizontally. More please!

Hannigan’s way with Berg’s Lulu-Suite was surprising. It took me a while to get used to, and there were unquestionably aspects of the music that went a little uncared for. That said, to hear it performed with such attention to the multifarious melodic strands - heard, I suspect, very much from a singer’s standpoint - was fascinating. So too was the relative lightness, almost Mendelssohnian, with which the first movement ‘Rondo’ was despatched. The big moments certainly told, but they were not everything. I am not sure I should always want to hear the music like this - indeed, I am sure that I should not - but to hear the classic Romantic/modernist dichotomy not so much evaded as avoided brought plenty of its own interest. Transparency is necessary no matter what the interpretative standpoint, of course; here, Hannigan and the LSO excelled. One might have taken dictation, vocal and verbal, from Hannigan’s sung contribution to the ‘Lied der Lulu’, which was ‘concert-acted’ too. Coloratura held no fear for her, but crucially, it was employed dramatically, just as in Mozart. If there were a few rough orchestral edges to the fourth movement, it is difficult to imagine them having bothered anyone but pedants. The final ‘Adagio’ emerged properly de profundis, as eloquent as if its lines were being sung. Hannigan’s melisma on ‘Engel’ truly told. Quite a performance, then, in so many ways.

The Gershwin suite with which the concert concluded proved equally fascinating - and perhaps still more thrilling. Conceived by Hannigan with the express purpose of accompanying the Lulu-Suite, its ingenious orchestration for identical forces was commissioned from Bill Elliott. As a Bergian, at times Mahlerian, soundworld unfolded, it did not jar. Quite the contrary: t drew one in, not only harmonically but also motivically, to the material of the three songs, ‘But not for me’, ‘Embraceable you’, and ‘I got rhythm’. Then, of course, there was Hannigan’s own star quality as a singer: different, perhaps, from the stars one often associates with this music, but in no sense less bright. It was sung as carefully as Berg had been, without ever sounding ‘careful’. The orchestra joined in with some vocal harmony too, but this was in every sense Hannigan’s show, ‘I got rhythm’ straightforwardly sensational.

Mark Berry

Ligeti: Concert Românesc; Haydn: Symphony no.86 in D major; Berg:Lulu Suite; Gershwin, arr. Barbara Hannigan and Bill Elliott: Girl Crazy: Suite. London Symphony Orchestra/Barbara Hannigan (soprano, conductor).

Barbican Hall, London, Sunday 17 March 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/barbara%20hannigan.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Barbara Hannigan and the LSO at the Barbican Hall product_by=A review by Mark BerryChristina Scheppelmann appointed General Director of Seattle Opera

SEATTLE—Christina Scheppelmann will become Seattle Opera’s fourth General Director in the company’s 56-year history. Beginning in August 2019, she replaces Aidan Lang, who will become General Director of Welsh National Opera following the end of the 2018/19 season.

“When we reached out to luminaries in the opera world, Christina Scheppelmann’s name kept coming up from all angles as being someone we needed to talk to,” said John Nesholm, Chairman of the Seattle Opera Board and Co-Chair of the Search Committee. “She brings incredible experience and knowledge of singers, directors, and productions from three continents.”

Born in Germany and fluent in five languages, Scheppelmann is currently the artistic leader of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, a 172-year-old company with an annual budget of €43 million, the equivalent of roughly $50 million. The historic theater produces more than 130 performances in opera, classical music concerts, dance, and more per season.

“For many years, I have admired Seattle Opera and attended performances here regularly when I was working at San Francisco Opera,” Scheppelmann said. “In my experience, there’s a unique enthusiasm, an engaged and dedicated audience that’s always felt special at Seattle Opera.”

Scheppelmann’s accomplishments in Barcelona include an Elektra produced in collaboration with the Metropolitan Opera, Teatro alla Scala, the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence, the Finnish National Opera, and the Staatsoper Unter den Linden. She has also brought important artists to Gran Teatre del Liceu including tenor Jonas Kaufmann, director Terry Gilliam (Monty Python) for Berloiz’s Benvenuto Cellini, and composer Luca Francesconi for the Spainish premiere of Quartett.

Previously, Scheppelmann was the first Director General of the Royal Opera House Muscat (Oman), the first theater of its kind in the Persian Gulf Region. Under her guidance, ROHM established an excellent reputation as a cultural destination in Oman and opened doors for international musical and cultural relations. As Director of Artistic Operations at Washington National Opera, Scheppelmann oversaw the artistic planning for 11 years in collaboration with General Director Plácido Domingo. She was instrumental in fundraising efforts that led to grants for individual productions, ongoing projects, and specific renovations. Some of her proudest accomplishments include an acclaimed concert performance of Götterdämmerung at the Kennedy Center Opera House in 2009. She also created WNO’s American Opera Initiative. Now going on its eighth season, the program offers young composers and librettists a developmental forum in which to bridge the gap between conservatory training and full-length commissions.

In 1994, Scheppelmann was recruited by Lotfi Mansouri at San Francisco Opera, and became one of the youngest artistic administrators at the time. In addition to season planning, hiring artists and creative teams, and building collaborative relationships within the industry, she contributed to the presentation of two major world premieres: Jake Heggie’s Dead Man Walking (2000) and André Previn’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1995), which quickly became one of the most widely played contemporary operas at the time.

“Scheppelmann is the leader Seattle Opera needs to move the company into a new era,” said Adam Fountain, a Seattle Opera Board Vice President and Search Committee Co-Chair. “She’s committed to new work, to helping the art form evolve, and to telling contemporary stories. She unites both where Seattle Opera has been, and where it’s going.”

Fountain, along with John Nesholm, led a search committee made up of eight board members total. The group included the current board president and two past presidents, plus four members representing the next generation of Seattle Opera Board leadership. During the six-month process to find Aidan Lang’s replacement, the committee met with multiple staff groups, including the company’s racial equity taskforce, made up of administrative staff members from a variety of departments and levels of the organization. An artistic advisory committee, made up of musicians, artists, and backstage crew, also met with the committee and each of the final candidates.

In the Seattle area, Scheppelmann becomes the only woman to hold the top artistic leadership position at a large theater or performing arts organization (with an annual budget of more than $10 million). In the opera world, she becomes one of only two women to lead a top-tier opera company in the United States.

Francesca Zambello, Artistic Director of Washington National Opera, said it’s especially meaningful to have another woman as a leader of a major U.S. opera company:

“I think of Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s famous comment when she was asked, ‘When will there be enough women on the Supreme Court?’ Her response was, ‘When there are nine.’ Women are such an important part of the stories we tell onstage, and they are key members of our staffs, our boards, our audiences. It is high time for more women to be represented in top leadership. Christina is greatly respected across the field, and is an ideal choice to lead Seattle Opera.”

A long-time champion of young artists, Scheppelmann has led masterclasses, lectured at artist training programs, and judged vocal competitions around the world. She began her career in the arts early on performing in the children’s choir of the Hamburg State Opera. After completing a degree in banking, she left her home country of Germany in 1988 to work in an Artist Management agency in Milan.

As a first order of business at the company’s civic home on the Seattle Center campus, Scheppelmann has made listening and learning about the community a priority in order to create a vision that not only propels opera into the 21st century, but is representative of the region and its people. On a personal note, she’s looking forward to enjoying the lush beauty of her new surroundings, kayaking, and playing golf on her days off.

“Seattle Opera has already established itself as one of the great American opera companies, and it can grow even further,” Scheppelmann said. “It has a fantastic history, from more recent work, to historic Wagner productions (some of which I have seen). Seattle Opera also has a world-class opera house with great acoustics, and now, a civic home which will add fantastic value to the community. Singers love coming to Seattle Opera, because they like the company and they like the city.”

About Seattle Opera

Established in 1963, Seattle Opera is committed to serving the people of the Pacific Northwest with performances of the highest caliber and through innovative educational and engagement programs for all. Each year, more than 95,000 people attend Seattle Opera performances, and more than 400,000 people of all ages are served through school performances, radio broadcasts, and more. By drawing our communities together, and by offering opera’s unique fusion of music and drama, we create life-enhancing experiences that speak deeply to people’s hearts and minds. Connect with Seattle Opera on Facebook, Twitter, SoundCloud, and on Classical King FM. 98.1.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ChristinaScheppelmann_Miralls_05.jpg image_description=Christina Scheppelmann product=yes product_title= product_by=Press release by Seattle Opera product_id=Above: Christina Scheppelmann [Photo courtesy of Seattle Opera]New perceptions: a Royal Academy Opera double bill

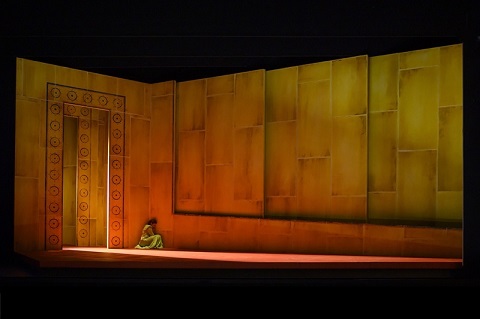

Indeed, a tale of a secluded, blind princess kept ‘in the dark’ about her affliction by an overprotective (oppressive?) father, and thus denied the life and love that might cure her, has more than a touch of Angela Carter about it. Tchaikovsky’s tale of Princess Iolanta’s physical and spiritual awakening was fashioned by Tchaikovsky’s brother, Modest, from Danish playwright Henrik Hertz’s drama ‘King René’s Daughter’, and while the libretto is hampered by some mawkish medieval allusions, any sentimentality is outweighed by the moving portrait of Iolanta’s sadness, suffering and sensuality.

Director Oliver Platt and designer Alyson Cummins suggest the young girl’s latent passion with minimal but effective means. A glasshouse bursting with verdant life intimates heated emotions and senses - colours, scents, tactility - which are the stuff of a life denied to Iolanta by the Provençal King René, who has threatened anyone who mentions sight or light with death, betrothed his daughter to Robert Duke of Burgundy (who wants out of the contract, so that he can marry his beloved Mathilde), and forbidden access to Iolanta’s garden. The ladies-in-waiting wear simple frocks that resemble nurses’ gowns, but their blue surgical gloves suggest a clinical coldness.

Leila Zanette (Marta, centre), Samantha Quillish (Iolanta, right). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Leila Zanette (Marta, centre), Samantha Quillish (Iolanta, right). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Samantha Quillish sang Iolanta’s arioso lines with delicacy in the opening garden scene, conveying the princess’s gentleness and purity, but her soprano has both depth and darkness and grew in fervency as Iolanta’s sensuality was awoken, passivity giving way to nascent but intense passion. As her father, Thomas Bennett made a good effort to strike a balance between the King’s patriarchal domination and paternal devotion, and demonstrated a pleasing bass, but one which still needs to develop a little more firmness and focus.

The two interlopers who bring light and life into Iolanta’s world brought energy and colour to the drama too. As Vaudémont - who ‘opens’ Iolanta’s eyes and to save whose life she agrees to undergo a cure for her blindness - Shengzhi Ren sang with power and ardency, and generally good intonation - just occasionally when rising to the heights he was a little under the note, but this was more than compensated for by vibrancy of tone and dramatic commitment. His extended duet with Quillish was rapturously redolent with hope and promise. Sung Kyu Choi brought vocal agility and colour to Robert’s single aria. Best of the chaps, though, was Darwin Leonard Prakash as Ibn-Hakia; the doctor’s monologue was notable for its expressive directness and strength of line.

Darwin Leonard Prakash (Ibn-Hakia) and Thomas Bennett (King René). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Darwin Leonard Prakash (Ibn-Hakia) and Thomas Bennett (King René). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The smaller parts were well-sung. Leila Zanette had presence as Marta, and the light, fresh voices of Emilie Cavallo and Yuki Akimoto, as Iolanta’s friends Brigitta and Laura respectively, blended sweetly. The roles of Alméric, armour-bearer to King René, and Bertrand, door-keeper to the castle were competently assumed by Joseph Buckmaster and Niall Anderson.

There were some directorial mysteries and mis-hits, though. While thereis an otherworldly stillness, reminiscent of Pelléas et Mélisande, about Tchaikovsky’s final opera, the immobility of the RA chorus members - who seemed pretty much left to their own devices - was a weakness. More seriously, Platt seemed determined to make a ‘point’ at the close, but it wasn’t one that was in accord with the opera’s most obvious ‘meaning’. In the aforementioned climactic duet for Iolanta and Vaudémont, as the latter tries to explain the meaning of ‘light’ Iolanta insists that she does not need light in order to worship her God - and Tchaikovsky’s score goes into orchestral-illumination overdrive. In a ‘conclusive’ choric statement, the ensemble shares in the transfiguration of Iolanta’s vision. So, she, and they, and we, see the light in all senses of the phrase. Here, the princess’s enlightenment was accompanied not by a blaze of illumination but by a night sky, sparkling with celestial bodies. Well, it suggested spiritual fulfilment and rapture. But, Platt’s parting comment was to have Iolanta collapse in whimpering distress as the dawn sun rose. Surely, her new perception comes from love, not from literal vision. Is Platt suggesting that the former was false or illusory? If the production had been braver, it might have essayed a ‘dark’ ending by suggesting that Iolanta - like Pannochka in May Night (which Royal Academy Opera performed in 2016 ) - is really ‘of this world’, and cannot form a true relationship with Vaudémont; in which case an ambiguously bleak ending might have been more convincing.

Olivia Warburton (L’enfant). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Olivia Warburton (L’enfant). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

By contrast, the illusions and disillusionments of childhood were depicted with unflinching honesty, in a beguiling production of Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges, in which Olivia Warburton’s superb embodiment of the méchant’s journey from adolescent solipsism to a more mature empathy winningly balanced humour and pathos. Warburton - whom I have recently admired as Ino in the RAO’s Semele and in the title role of the London Handel Festival’s 2018 production of Teseo - sang with a pure tone - and lovely limpid French diction - that conveyed, initially, self-conviction and indignation, and latterly, vulnerability and awakening. She stomped, rioted, flinched and cowered with gamine gall and gullibility as l’enfant’s dreams of freedom morphed into a fearful dread, and the garden of promise became a gothic prison.

Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Ravel’s opera is a perfect choice for a student production, offering as it does a range of divergent characters who must be swiftly embodied in voice, movement and costume; and, on this occasion singing, design and choreography came together with a directness and simplicity - and ‘dark undertone’ - which was compelling. Not so much whimsey as witchery. This was not a picture-book, cutesy childhood milieu: bookshelves and central bed were messy; matching tents on opposite sides of the stage spilled fire, frogs and other fantastic fare to taunt the petulant youngster; there was an underlying grittiness, as when the child angrily ripped down his paper-thin walls to ‘escape’ into the garden.

Lina Dambrauskaitė (Le feu). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Lina Dambrauskaitė (Le feu). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Conductor Gareth Hancock whirled us through the rapidly succeeding episodes creating a dream-like disorientation and spontaneity. The vocal roles are ‘small’ in the sense of ‘brief’, but they really need to make their mark with succinct directness, and so they did. La bergère (Aimée Fisk) and Le fauteuil (Will Pate) combined vocal clarity and strength of purpose in escaping the mischievous imp with Louis quatorze dignity; James Geidt’s L’horloge comtoise was aptly piqued having had his pendulum pinched. The piquant dance between La théière (Ryan Williams) and La tasse chinoise (Hannah Poulsom) suggested that they shared a bitter brew rather than a jazzy syrup. Hand-puppets and dragon-fly wands conducted a surreal bombardment as the tormented animal kingdom bit back, the crudeness of the design perfectly capturing the unsophistication of the child’s world. Especial mention should go to Lina Dambrauskaitė whose Fire shone with the sort of gleaming vocal intensity and brightness that we heard last year when she sang the title role in Semele, and Alexandra Oomens who was a radiant and dramatically commanding Princess.

Having evoked Tchaikovsky’s strange sound world with security and expressiveness, the Royal Academy Sinfonia were occasionally challenged by some of the many demands that Ravel makes of the instrumentalists, but they conjured the varied musical styles with flair and colour.

Claire Seymour

Tchaikovsky: Iolanta

Iolanta - Samantha Quillish, Brigitta - Emilie Cavallo, Laura - Yuki

Akimoto, Marta - Leila Zanette, Vaudémont - Shengzhi Ren, Alméric - Joseph Buckmaster, Robert - Sung Kyu Choi, Ibn-Hakia - Darwin Leonard Prakash, Bertrand - Niall Anderson, King René - Thomas Bennett.

Ravel:

L’enfant et les sortilèges

L’enfant - Olivia Warburton, La princesse/La chauve-souris - Alexandra

Oomens, Le feu/Le rossignol - Lina Dambrauskaitė, La théière/La rainette/Le

petit vieilliard - Ryan Williams, Maman - Tabitha Reynolds, La tasse

chinoise/La llibellule - Hannah Poulsom, La bergère/Une pastourelle/La

chouette - Aimée Fisk, La chatte/L’écureuil - Gabrielė Kupšytė, L’horloge

comtoise/Le chat - James Geidt, Le fauteuil/L’arbre - Will Pate.

Director - Oliver Platt, Conductor - Gareth Hancock, Designer - Alyson Cummins, Lighting Designer - Jake Wiltshire, Movement and Puppetry - Emma Brunton, Royal Academy Opera Chorus, Royal Academy Sinfonia.

Susie Sainsbury Theatre, Royal Academy of Music, London; Monday 18th March 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Iolante%20and%20Vaudemont.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Iolanta and L’enfant et les sortilèges product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id= Above: Samantha Quillish (Iolanta) and Shengzhi Ren (Vaudémont)Photo credit: Robert Workman

March 17, 2019

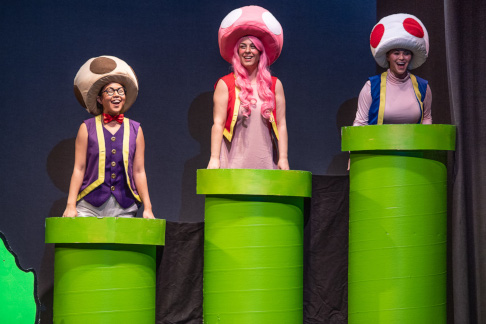

Desert Island Delights at the RCM: Offenbach's Robinson Crusoe

Even a desert island might look more appealing than an island that seems to be heading for its just deserts. As one band of shipwrecked adventurers ruefully reflect - in Don White’s English translation of Jacques Offenbach’s Robinson Crusoe - nineteenth-century Britannia may rule the waves but it’s a land where cheats and charlatans - financial and political - prosper: sometimes it’s sweeter to be “homesick” than “sick of home”.

As far as French musical anniversaries go, Berlioz’s 150th has had more prominence so far this year than Offenbach’s 200th, but the Royal College of Music Opera Studio has re-balanced the scales with this sparkling performance of Offenbach’s 1867 opéra comique in which romantic idealism replaces the racist imperialism of Daniel Defoe’s novel, a text that celebrates its own three hundredth birthday this year.

Robinson Crusoe was Offenbach’s second attempt to get a foot in the door of the Opéra Comique, but though reports suggest that the premiere at Paris’ Salle Favart was well-received, after a 32-performance run it faded from view, making intermittent appearances (in New York in 1875 and - in an altered version, Robinsonade - in Leipzig in 1930) before arriving on British shores in 1973 in a Camden Festival production by Opera Rara. Performed by the latter at the Proms and recorded in 1980, Robinson Crusoe was taken on a tour of the Isles by Kent Opera in 1983 and has popped up every ten years or so: Jeff Clarke’s translation was performed by Opera della Luna in 1994; the Iford Festival presented it in 2004.