April 30, 2019

Verdi: Messa da Requiem - Staatskapelle Dresden, Christian Thielemann (Profil)

Adorno would slightly backtrack in his later work, Negative Dialects, where he suggested it might have been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poetry - though he would become even more damning about the colossal existential terror of the guilt and insanity of its horrors. Adorno’s vision for the survivors of events such as the Holocaust is almost Kafkaesque; but, one might equally argue that Paul Celan’s poem Todesfuge says everything that needs to be said about war and its horror.

Composers who lived through the war have tended, like Adorno, and even the Romanian-born poet Celan (who wrote largely in German) to focus on the victims of Nazi oppression: Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw or Nono’s Ricorda cosi ti hanno fatto in Auschwitz are just a couple of notable examples. Where composers have taken a view on allied destruction elsewhere they have particularly centred on Japan and the nuclear cataclysm: Penderecki’sThrenody to the Victims of Hiroshima and Nono’s Canti di vita e d’amore: sul ponte di Hiroshima. Only the openly-pacifist Benjamin Britten in his War Requiem could be said to have taken an entirely universal (though hardly neutral) position on the pointlessness of war. Richard Strauss, who in Metamorphosen, and even the Vier Letze Lieder, wrote music which came closer to elegy, music that looked back into the past through the ruins of the present. Most German composers have rather avoided tackling the subject of the destruction of their own cities altogether, perhaps because the subject is too raw to address.

Dresden was, and remains, one of the clearest examples of a German city ruined in the same way as the cities which drew in Britten, Penderecki and Nono - widely accepted today to have been at least indiscriminate, and probably questionable. Historically, its relationship with music is almost as old as European classical music itself, though after the war, the anniversary of its destruction, remembered on a single day, has been closely defined by an Italian requiem - Verdi’s.

Identification in music for reviewers can be related to the circumstances of our birth as much as it is to the objectivity of the performances before us. Striking that balance can sometimes be problematic, however. Questions of guilt, responsibility - and even Adorno’s premise that one is somehow corroding the very basis of atonement - can make one extremely wary of even approaching such a review in the first place. But with a German ancestry - and connections to Dresden - I wanted to hear and write about Christian Thielemann’s new recording of Verdi’s Requiem from the distance of time - and the commemoration of the destruction of this great city - remembered each year in its annual concert.

Thielemann’s concert of the Requiem is not in itself a one-off performance. Since 1951, starting with Rudolf Kempe, the Dresden Staatskapelle and chorus of the Staatsoper has given a concert of Verdi’s Requiem on the 13th February every year on Dresden Memorial Day - although in recent years a different work has often been played. (I recall a Missa Solemnis, this year it was Dvořák’sStabat Mater and in 2020 it will be Purcell’s Funeral Music for Queen Mary and Mahler’s Tenth.) It has mostly been the case that these concerts have been played on three nights - two in the Semperoper, and one in the Frauenkirch. The occasion is marked by reconciliation and tolerance, of shared hope and peace. Those first performances under Kempe were played in the shattered Staatstheater - and the destruction of the city, the memories of the apocalypse of the firestorm which had swept through it were still fresh - much as they were for much of mainland Europe and the major cities of Japan and the Far East at the time. The performances then - as they are now - are premised on coexistence and not division, on healing and not the wounds of war. Even when you return to Dresden many decades after the events of the Second World War pockets of the city show scars of its destruction that may never be entirely erased; but that is equally common if you walk the streets of Warsaw or Coventry as well.

Although Christian Thielemann is most closely identified as a conductor from the Germanic tradition, his immersion into Italian repertoire has been convincing (Otello was performed by him at least as far back as 1996, and the Quattro Pezzi Sacri has often been programmed as well). Although this Dresden Verdi Requiem is the earliest one by him I can recall hearing, it is by no means his only one. It’s true that if you’re looking for anything resembling an overtly ‘Romantically’ phrased performance with Italianate warmth you probably need to look elsewhere - though this Dresden Requiem makes considerably more of a statement than one performed a year later at the Salzburg Festival. There is undoubtedly a sense of reverence to it - something which at Easter in Salzburg 2015 had been replaced by something altogether less fragile and certainly less spiritual.

The Dresden Staatskapelle is no stranger to Verdi’s Requiem - Sinopoli, in one of his final performances before his death, gave the Dresden Memorial Concert from the Frauenkirch on 13th February 2001 - a recording which has only ever been issued on a private label. Christian Thielemann does take a different approach to the work, in part, I suspect, because the sound of the orchestra can be quite markedly darker than Sinopoli brought to it - not that he brings much warmth to the Dresden sound either, especially in the strings which have surprising weight (Sinopoli, however, has a more lightweight quartet of singers than Thielemann mustered for this performance). Additionally, in the past there have been noticeable differences between Profil’s engineering of their CDs versus the actual broadcasts they have used (Sinopoli’s Ein Heldenleben was virtually ruined by Profil) - but that is certainly not the case here. The space allowed around the orchestra is exceptional, the clarity of the playing is crystal clear and there is a detail and depth to the performance which is faithful to the acoustics of the Semperoper. Profil haven’t sought to adjust some of the inherent balance problems between the orchestra and soloists either - if you sometimes strain to hear Krassimira Stoyanova climb above the orchestra and choir that’s because she was slightly overwhelmed by both in the performance. Does this matter? No it doesn’t because although Stoyanova is still audible at those climaxes it’s what she does with her voice that matters and there’s a powerful underlying struggle in her phrasing which is remarkable.

Thielemann’s view of the Requiem is rather similar to Sinopoli’s in one respect in that both take a dramatic - though that is not to say operatic - view of this work. There are spiritual overtones (perhaps undertones would be a better word), but you have to search deeply for them. Sinopoli is slower at the opening of the ‘Dies Irae’ - those massive timpani are like rolling thunder; Thielemann sees them more as a shocking, explosive blast - and it’s rather more terrifying as a result. Some have criticised Sinopoli for smothering this music, almost choking it, so it sounds a little underwhelming - but this is not something I particularly hear in his Dresden Requiem. Thielemann does drive the ‘Dies Irae’ onwards - though, as you might expect from such an experienced Bruckner conductor, that drive is almost entirely shaped by a singular line of thinking. It’s easy to fragment the ‘Dies Irae’ - Thielemann doesn’t do this; the arc in which its span is taken is impressively extended, like a singular breath that never seems to quite come up for air. This can be challenging for his soloists - but whether it’s the dark-hued, solid but monumental ‘Tuba mirum’ of the bass, Georg Zeppenfeld, or the magnificently rich-toned ‘Ingemisco’ of the tenor, Charles Castronovo, it’s a contrast of colour that Thielemann achieves as well as the perfect line that never feels like it’s just stitched together like fragments of the liturgy. The ‘Quid sum miser’ is like a spiral, the mezzo of Marina Prudenskaja such a beautiful foil to Stoyanova’s soaring soprano. Perhaps the chorus in the ‘Lacrymosa’ sound a touch loud, just occluding the soloists - but as I suggested earlier this is a performance which gets its strength from the ambience of its struggle.

There are times you listen to Verdi’s Requiem and everything after the ‘Dies Irae’ can seem like a slow descent into anti-climax. Sinopoli was never one to do this - even in the couple of recordings we have of his which he made outside his Dresden concert - and Thielemann doesn’t either. There is a change in the pace of the work, though it’s possibly even harder to keep a good performance on track. I can’t really fault the way in which Thielemann balances the orchestra and double chorus through the ‘Sanctus’ - the sense of divisi has remarkable clarity. You get this, too, in the ‘Agnus Dei’ where Prudenskaja and Stoyanova are in such perfect harmony with the chorus - the orchestra just weighty and rich enough so it wraps like a shroud around the voices. If many conductors see the ‘Libera me’ as a climax to the Requiem, Thielemann views it as a true coda - not the actual end of it, but the complete summation of everything that has come before it. If you listen to the power - and reverence - behind Thielemann’s ‘Libera me’, in the closing bars you could be listening to the final pages of Bruckner’s Fifth or Eighth Symphonies. This is, in part, what makes this Verdi Requiem rather special and unique.

I think this is one of those performances which can stand alongside some of the great recordings of the past - de Sabata, Cantelli, Giulini - and, perhaps, Sinopoli in Dresden, too. It’s beautifully sung, conducted and recorded - I’m not sure you could ask for much more.

Marc Bridle

Verdi: Requiem

Krassimira Stoyanova (soprano), Marina Prudenskaja (mezzo), Charles Castronovo (tenor), Georg Zeppenfeld (bass), Christian Thielemann (conductor), Staatskapelle Dresden, Dresden State Opera Chorus.

Recorded 13th February 2014 at Semperoper, Dresden.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Verdi%20Thielemann%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Verdi: Requiem: Edition Staatskapelle Dresden - Volume 46, PROFIL PH16075 [43.43 + 37.37] product_by=A review by Marc BridleApril 29, 2019

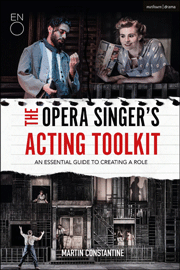

The Opera Singer’s Acting Toolkit

“Drawing upon the innovative approach to the training of young opera singers developed by Martin Constantine, Co-Director of ENO Opera Works, The Opera Singer's Acting Toolkit leads the singer through the process of bringing the libretto and score to life in order to create character. It draws on the work of practitioners such as Stanislavski, Lecoq, Laban and Cicely Berry to introduce the singer to the tools needed to create an interior and physical life for character. The book draws on operatic repertoire from Handel through Mozart to Britten to present practical techniques and exercises to help the singer develop their own individual dramatic toolbox.”

“Drawing upon the innovative approach to the training of young opera singers developed by Martin Constantine, Co-Director of ENO Opera Works, The Opera Singer's Acting Toolkit leads the singer through the process of bringing the libretto and score to life in order to create character. It draws on the work of practitioners such as Stanislavski, Lecoq, Laban and Cicely Berry to introduce the singer to the tools needed to create an interior and physical life for character. The book draws on operatic repertoire from Handel through Mozart to Britten to present practical techniques and exercises to help the singer develop their own individual dramatic toolbox.”

Ravel’s L’heure espagnole: London Symphony Orchestra conducted by François-Xavier Roth

The work which you might have expected to end the program, Boléro, one of the great orchestral showpieces, didn’t come at the final stretch which may in the end have been just as well; this was a performance which didn’t really do much for me, not that it stopped most of the audience thinking otherwise.

L’heure espagnole - as its title suggests - runs close to an hour in length, though at times Roth seemed close to edging it faster. This is Ravel at his most imaginative, the composer astonishingly vivid in his scoring - in one sense this is an opera that literally vibrates, ticks and tocks, clicks with the pulse of swaying metronomes - quite literally, in fact - and has the rhythm of mechanics running through it. It predates Varèse by decades - and who would turn to science, mechanics and the influence of key thinkers like da Vinci in his aural landscapes - but Ravel’s opera is every bit as inventive, if necessarily more primitive in its thinking.

Ravel described L’heure espagnole as an opéra-bouffe - and the best performances of it draw on high comedy and emphasise the sense of ordinariness of the characters. This may be less obviously easy to do in a concert performance as we had here - but it worked because the cast largely achieved that by entering and leaving at the wings of the stage rather as the libretto demanded. It certainly helped that they weren’t just sat there doing nothing (which would have been a travesty for the role of Torquemada, who is supposed to be out for the ‘hour’ winding the town’s clocks, while his wife, Concepción juggles - without much success - between her clumsy lovers).

In every sense this is an opera about time and timing - the muleteer Ramiro stops by to have his watch fixed, Torquemada has to tend to the town’s clocks (so Ramiro has to wait), Concepción doesn’t even have a clock in her bedroom but wants one there, Gonzalve, a poet more interested in his love for words rather the love of another kind, and is eventually stuffed into a clock he can’t get out of, and the banker Don Iñigo hidden in another clock, are metaphors within a comedy. It requires a better than average cast to bring all this off, especially when they’re largely confined on a stage in front of a conductor. To their credit, the five singers did a very notable job of doing just that.

It helped that the surtitles were very funnily translated - and they were even a touch double-edged in their meaning. It was just as well we had surtitles because I found some of the French being sung extraordinarily difficult to follow, even to the extent I sometimes wondered at times what language I was hearing; I’ve rarely heard this opera sound quite that vocally mangled. But never mind. The comedy ended up being beautifully timed. The acting, although it could have been limited by space, was not just considered, it was a joy to watch and very expressive, comic without feeling forced - soaking up every ounce of farce like a sponge from a libretto that sometimes challenges its singers to do so.

Jean-Paul Fouchécourt’s Torquemada rather left no doubt as to why Isabelle Druet’s Concepción might seek amour elsewhere - but how perfect they were as an imperfect coupling. If Fouchécourt engaged with the female violinists of the LSO, in flirtatious exits and entrances, more than he ever did with his wife, Druet’s Concepción left no doubt why the dynamics of this relationship were always in disarrangement. On the one hand, you had the small, but always superbly well-crafted tenor of Fouchécourt, set beside the powerful, sleekly engineered grandeur of Druet’s soprano. It was perhaps a little more lyrical than one might expect - but it worked like clockwork. An ideal couple who revelled in the comedy of being singularly unideal.

Thomas Dolié’s Ramiro was undeniably strapping - a singer who has the kind of rip-roaring baritone that easily strides over an orchestra. But he clearly understood the role as well bringing a silky pathos when needed and an all-knowing understanding to the sexual double-dealing of Concepción. Gonzalve can sometimes seem difficult to cast - it needs a singer who somehow needs to inhabit two rather indistinct worlds. Edgaras Montvidas effortlessly sang the role with much expression, but he was also able to define the poet who rather seems aloof from reality. His tenor was probably the most shining voice of the evening, the one which came closest to mirroring the precision and beauty that came from the orchestra. In Nicholas Cavallier’s Gomez - the grey-haired banker - one related to his ego, and his failures.

Roth’s conducting - as it had been in the first half of the concert - often seemed on the brisk side, but this was also a beautifully proportioned, often mesmerising performance, exquisitely played, by an LSO that didn’t always seem comfortable in this idiomatic music. Indeed, I had found the opening Rapsodie espagnole - a work which in the wrong hands can often outstay its welcome - come tenuously close to drifting off completely. Roth seemed so intent on contrasting the slow and fast sections of this score that I felt I was on a helter-skelter. The opening prelude took a while to get going - and one never really felt that those languorous passages Ravel went to great effort to highlight shadows and time in the music did anything other than linger. On the other hand, there was a Feria which felt fiery - but it came just a little too late. Boléro, too, didn’t really wow me as some other performances have done. There are some conductors who feel they need to conduct this work, and those who feel the work can just play itself - Roth falls into the first category. Brushing aside the distinctly un-French sound of the LSO, especially in the woodwind here (and which actually didn’t at all seem noticeable during L’heure espagnole), and some uncommonly lazy playing, this was a performance which tended to run on the fast side. Roth knows how to ratchet up the tension and suspense in Boléro - this performance felt like a screw tightening - and the climax felt colossal. But if you were looking for something that strived towards the oriental, or that looked into the deeper mechanical workings of a score where each player seems to play like a welder hammering metal, or a mason carving stone this performance wasn’t it.

Earlier in the evening I had caught a short concert of Ravel’s String Quartet in F major. Given by the Marmen Quartet - as part of the Guildhall Artists series - this was a performance which didn’t necessarily seek enormous depth in a work which looks to Debussy’s Quartet for its inspiration. There was no lack of precision here, nor an unwillingness to highlight the shadowy writing that separates the upper and lower instruments; contrast was a hallmark throughout. There was an impressive sense of taking the music in a single arc during movements, even when the time signature changes - as in the Vif et agité. If a single player grabbed my attention it was the cellist, Steffan Morris. His tone is deep, beguilingly rich - even sumptuous. He added weight to a performance which sometimes seemed to spurn it.

This concert will be broadcast on BBC iPlayer on 30th April and will be available for 30 days.

Marc Bridle

London Symphony Orchestra - François-Xavier Roth (conductor)

Isabelle Druet (soprano), Jean-Paul Fouchécourt (tenor), Thomas Dolié (baritone), Edgaras Montvidas (tenor), Nicolas Cavallier (bass-baritone)

Marmen Quartet - Johannes Marmen (violin), Ricky Gore (violin), Bryony Gibson-Gore (viola), Steffan Morris (cello)

Barbican Hall, London; 25th April 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LSO%20and%20FXR%20by%20Doug%20Peters%20%281%29%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Ravel: L’heure espagnole: London Symphony Orchestra at the Barbican Hall product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=Above: François-Xavier RothPhoto credit: Doug Peters

Breaking the Habit: Stile Antico at Kings Place

This varied programme, captivatingly sung by the twelve-strong a cappella ensemble, Stile Antico, celebrated such women, exploring diverse issues and domains from monarchs to musicianship, from the court to the convent.

The short, troubled reign of Queen Mary I (1553-58) has long been overshadowed by that of her half-sister Elizabeth, her five years on the throne judged as unsuccessful, bloody and unfruitful. However, her achievement in assuming the throne and becoming England’s first female sovereign is increasingly being reassessed. Moreover, her strict imposition of Catholicism upon her nation may have resulted in the deaths of up to 300 of her Protestant subjects, but the reestablishment of the Catholic services which had been abolished by Edward VI meant that the musicians of the Chapel Royal had to revive and develop the musical liturgy.

The Latin Church music of Thomas Tallis and John Shepherd exemplifies the refreshing of this liturgical tradition. Tallis’s Pentecostal office responsory ‘Loquebantur variis linguis’ is brief but presents rich elaboration around the tenor cantus firmus, and the full complement of twelve voices relished its piquant harmonies, blending mellifluously. Performing without a conductor they seem to communicate by quasi-telepathic means so assured is the ensemble and collective expressivity. John Sheppard’s ‘Gaude, gaude, gaude Maria’, a responsory for Candlemas, is both more obvious in its homage to the monarch, whose namesake it celebrates - “Rejoice, rejoice, rejoice, Virgin Mary!” - and even more majestic. Stile Antico pristinely delineated the counterpoint, used harmonic and cadential nuance to bring significant textual phrases to the fore - “inviolate permansisti” (you remained an undefiled virgin) and grew with sweet strength towards the concluding “Gloria”.

These were unsettled times for English musicians, though, and with the ascension of Elizabeth I it was ‘all-change’ once more. William Byrd’s ‘O Lord make thy servant Elizabeth’ reflects the monarch’s new injunction for textual clarity; here, the ensemble sound was consoling and warm - aptly so, for the Catholic Byrd prays for the well-being of the woman who offers him both patronage and protection from religious persecution. The polyphony was smooth and calm, culminating in a gloriously florid “Amen”. John Taverner had been master of the choir in Cardinal College Oxford (now Christchurch), where he had forty voices at his disposal and the buoyant ‘Christe Jesu, pastor bone’, a votive antiphon to be sung after Compline, reflects the potential offered by the large forces. It was originally composed in honour of St William of York, but later adapted to serve as a prayer for both the monarch and her Church. The concluding request that they both be granted the reward of eternal life was fittingly positive in spirit and glowing in tone.

In 1601 Thomas Morley published a collection of madrigals in honour of Elizabeth, The Triumphs of Oriana, to which John Bennet contributed ‘All creatures now are merry minded’ which was sung with up-lifting lightness and joy. Richard Carlton was vicar of St Stephen's church, Norwich, and a minor canon at Norwich Cathedral; he too contributed to Morley’s publication, and ‘Calm was the air’ which the nine voices brought to a radiant conclusion of shining, rising scales, “Long live fair Oriana!”, grounded by a sonorous low bass.

On the continent, the Netherlands had come under Habsburg control through the marriage in 1477 of Maximilian I to Mary, daughter of Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. During the fifteenth century the Burgundian court had emerged as a centre of cultural splendour and musical patronage, and on her appointment as Regent of the Netherlands, Margaret of Austria inherited the Grande chapelle on of the most impressive musical establishments in Europe, rivalling even the Papal chapel. Margaret’s cultural and musical patronage is reflected in the music manuscripts that survive from her regency.

Alexander Agricola (1446-1506) joined the Burgundian court in 1500. His music was described vy one 16th-century observer as ‘unusual, crazy and strange’, and some scholars have suggested that his it lies in-between vocal and instrumental idioms and has an almost baroque sensibility. Certainly, the motet ‘Dulces exuviae’, a setting of Dido’s lament from Virgil’s Aeneid sung here by eight voices, seemed to combine musical sentiments both sensual and sacred, moving restlessly towards a slightly tentative and inconclusive final cadence. The motet ‘Absalon, fili me’, attributed to Pierre de la Rue, is similarly unpredictable and experimental. It includes a reference to “frater mi Philippe”, suggesting that the text may have been written by Margaret herself in remembrance of her brother who died in 1506. Stile Antico wrung every drop of emotion from the extraordinary, almost painful, harmonic twists and turns as an arpeggio-motif descended despairingly.

Stile Antico celebrated not just female patrons but the producers of music too. Raffaella (also known as Vittoria, her name before she took religious orders) Aleotti (b.1575) was the second daughter of Giovanni Battista Aleotti, a prominent architect at the court of Duke Alonso II d’Esta. A child prodigy, in 1589 she entered the Convent of San Vito in Ferrara which was known for its musical training and performance, and during the following few years seems to have nurtured a growing religious vocation and considerable skill as a composer. During Holy Week in 1593, a Venetian Count visited the convent and was shown some madrigals, setting texts by Guarini, which Aleotti had composed; he published them, and later that year a collection of motets in five, seven, eight and ten voices also appeared, attributed to Aleotti. She subsequently took her vows, but continued to develop her musical skills becoming renowned as an organist and instrumentalist.

Given Aleotti’s young age when she wrote ‘Exaudi, Deus, orationem’, the motet’s harmonic daring and piquancy is striking, and Stile Antico brought forth the very human passion of this plea to the Lord through the varied vocal combinations and interplay. Aleotti was not the first female composer to see her music in print: in 1568 Maddalena Casulana (fl.1566-83), a skilled lutenist and singer, published a collection of madrigals whose dedication to Isabella de’Medici Orsini asserted its intent to ‘show to the world the foolish error of men who so greatly believe themselves to be the masters of high intellectual gifts that these gifts cannot, it seems to then, be equally common among women’. ‘O notte, O ciel, O mar’, sung by four voices here, proves her point through its dynamic response to the text and startling harmonic contortions and Stile Antico also captured the flexibility and sensitivity to the text of ‘Vagh’ amorosi augelli’.

A contemporary of Aleotti, Sulpita Cesis (b.1577) also took holy orders, in the Augustinian convent of San Geminiano in 1593. She published a volume of Mottetti spiritual in 1619, from which we heard ‘Ascendo ad patrem’ - the eight voices, arranged into two choirs, bringing vivacity to the central ‘Alleluia’ and lightness to the closing image of truth and certainty - and the similarly joyful and lively ‘Cantemus Domino’. Reminding us the music of some of these women composers would first have been heard in convent chapels, five ladies from Stile Antico performed two works by Leonora d’Este, (1515-75), the daughter of Duke Alfonso of Ferrara and Lucrezia Borgia who, upon her mother’s death was sent to the Clarissian convent of Corpus Domini. Both ‘Veni sponsa Christi’ and ‘Ego sum panis vitae’ were notable for their melodic fluidity, as the parts interweaved and crossed, and calm devotional air.

Lastly, Stile Antico performed a new work by Joanna Marsh, Dialogo and Quodlibet, which the composer describes as a ‘parody piece based on the conversations found in the Dialogo della Musica of Antonfrancesco Doni [1544] … a sizable volume containing a selection of contemporary pieces that Doni uses as a schema for analysing music and commenting on its performance’. As the six male singers huddled around a volume at the centre-front of the stage it was not hard to imagine the philosophical disputations of academies such as the Florentine Camerata de’ Bardi; or the series of musical polemics during the 16th century, such as that between Zarlino and Monteverdi following the publication of the latter’s fourth book of madrigals.

Conflict between old and new is not rare in the annals of music history, whether it is a result of changes in musical theory or new voices challenging those of established repute. Certainly, the six female singers at the rear of the platform, with their backs turned on us, were intent on debate and disruption. And, as we alternated between their delivery of fragments from Casulana’s dedication and the men’s dry discussion, the latter presented by Marsh in a rigid contrapuntal idiom which mocked the scholarly theorising, the ladies came to the forestage, declaring proudly: “Our wish is to entertain each other, not to hold school!” - a bold wish which outshone the men’s fading discourse, “A pox upon these clefs; this piece has different words you see; the discourse of a good musician, talk well of music.” Marsh’s composition raised many a chuckle from the Hall One audience and neatly combines insouciance of style with a serious intellectual challenge.

Everything about this concert had been meticulously prepared, from the spoken prefaces, to the re-arrangements of the singers’ semi-circle and resultant entrances-and-exits. But, while the latter were executed with the same flawless professionalism that characterised the singing itself, they did necessitate quite a lot of stage ‘traffic’. I wondered whether Stile Antico might have placed chairs at the rear and sides of the Hall One platform, from which they might rise to take their places as required, thereby facilitating smoother ‘transitions’?

However, the minor distraction in no way marred the glories of the music-making offered here. The male scholars may have ‘talked well of music’, but Stile Antico gave a rich, powerful voice to the women who patronised, produced and published such music and were very much part of the Renaissance.

Claire Seymour

Stile Antico: Breaking the Habit

Raffaella Alleotti - ‘Exaudi Deus orationem mean’; Pierre de la Rue - ‘Absalon fili mi; Anon. - ‘Se joue souspire/Ecce iterum’; Alexander Agricola - ‘Dulces exuviae’; Maddalena Casulana - ‘O notte, o ciel, o mar’; Sulpitia Cesis - ‘Ascendo ad patrem’; Leonora d’Este - ‘Veni sponsa Christi’, ‘Ego sum’; Maddalena Casulana - ‘Vagh’ amorosi augelli’; Thomas Tallis - ‘Loquebantur variis linguis’; John Sheppard - ‘Gaude, gaude, gaude Maria; William Byrd - ‘O Lord, make thy servant Elizabeth’, John Taverner - ‘Christe Jesu, pastor bone’, John Bennet - ‘All creatures now are merry minded’; Richard Carlton - ‘Calm was the air’; Sulpita Cesis - ‘Cantemus Domino’; Rafaella Aleotti - ‘ Angelus ad pastores ait; Joanna Marsh - ‘Dialogo Quodlibet’.

Kings Place, London; Saturday 27th April 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Stile-Antico030.png image_description=Stile Antico [Photo: Marco Borggreve] product=yes product_title=Breaking the Habit: Stile Antico at Kings Place product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Stile AnticoPhoto credit: Marco Borggreve

April 28, 2019

The Secrets of Heaven: The Orlando Consort at Wigmore Hall

And, a good job it was too, or concerts such as this survey of English music spanning some two hundred years, from the closing decades of the thirteenth century to the end of the fifteenth, would not be possible, given the fragmentary nature of English manuscripts - thanks to the reformers of the sixteenth century. Fortunately for singers such as The Orlando Consort, continental manuscripts often ‘fill in the gaps’ of works preserved only partially, or not at all, in England.

However, there are some English sources, such as the Egerton and Ritson MSS and, most significantly, the Old Hall Manuscript - a parchment book compiled mostly in the 1410s which provides us with compositions of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries by some of the musicians mentioned above. The Old Hall was copied for use in the royal chapels, initially in the chapel of King Henry V’s brother, Thomas Duke of Clarence. Later additions were made in the early 1420s by members of the Chapel Royal who served the young King Henry VI. Further additions provide evidence of the way the repertory was continually renewed by new generations.

The Orlando Consort’s performance of this music was immaculate. One could sense the four singers continuously assessing and adjusting the balance between the voices, to ensure that the rhythmic impetus and smooth melodic flow - characteristic of the ‘English school’ that flourished in the 1400s - were maintained, while also bringing features of harmony and rhythmic complexity to the fore. Textures were clear and clean, the expressiveness deriving from the effect of the whole rather than from any individual textual or musical gesture.

The music of John Dunstaple (c.1390-1453) is not included in the main corpus of Old Hall, though there were later additions, but his reputation and royal connections have ensured that his music (how much of his oeuvre, though?) has survived and is well-known today. The Orlando Consort began with one of Dunstaple’s best-known works, the motet Veni Sancte Spiritus/Veni Creator Spiritus, which was composed for performance in 1416 at a thanksgiving service at Canterbury Cathedral, after the Battle of Agincourt. The complexities of this grand motet, with its simultaneous triple texts, were delineated graciously, the voices blending well - first in the introductory duets, the treble line burgeoning melodically around the tenor’s statement of the chant, later as a quartet. Increasingly swelling in amplitude, The Orlando Consort at times suggested a greater number than their own four voices. This enhanced the growing mood of excitement in the text, which is complemented by the diminution of the rhythmic values in the lower voices. Such technical difficulties were negotiated with ease.

At the end of the first half we would hear Dunstaple’s ‘Quam pulchra es’ (ATB), mellifluously sung, and ‘Descendi in ortum meum’ à 4. Alto Matthew Venner exploited the rich expressiveness of the latter’s decorative treble line, and there was strong energy in the positioning of the treble against the lower three voices - first sustained, then imitative - at the close. The Orlando Consort’s attentiveness to the potential for variety in the shaping of phrase-endings was effective.

But, before this we then took a short detour back to the years of the late-thirteenth and early-fourteenth centuries for three three-part works, their composer’s identities unknown but unmistakably of the English school. ‘Alleluia, Christo iubilemus’ (c.1290) was buoyant and full of joyful vigour, accented phrases providing real rhythmic ‘swing’. The voices often wound quite closely together, the unison ‘Alleluia’ which closed the first and last sections presenting a strong contrast and sense of happy resolution. The gentle homophony of ‘O sponsa Dei electa’ (1300, Worcester Fragments) was easeful and reverential while ‘Kyrie Cuthberte prece’ opened with a flourish of praise and featured striking harmonic twists to illuminate such textual images as “On those who celebrate his honour bound as captives in the flesh, have mercy”. It was rhythmically precise and sung with a lovely ‘open’ sound.

Leonel Power (d.1445) was of the generation preceding Dunstable and his music is well-represented in the Old Hall Manuscript. The ‘Gloria’ heard here (for TTB) indulges in virtuosic mensural complexities and The Orlando Consort generated a strong sense of expanse, excitement and confidence - perhaps a little too much so, as it encouraged the audience at Wigmore Hall, not for the first or sole time during the evening, to leap in with vigorous applause before the concluding cadence had had time to fully settle. The long lines of ‘En Katerine solennia’ (ATB) by Bittering (fl.1410-20) and the triple-time lightness of Roy Henry’s ‘Sanctus’ (ATT) (both contained in Old Hall) were followed by an anonymous Credo from the Second Fountains Abbey Manuscript, a joyous celebration of faith delivered here with sprightly dotted rhythms and textual clarity.

After the interval we continued our time-spanning journey with more works by composers unknown. In a Stella celi from the Trent Codices, the addition of lower tenor and bass to the initial treble and high tenor pairing brought a lovely sense of broadening, complemented by a richly expressive “O gloriosa stella maris” (O glorious Star of the Sea) and increasing propulsion through the plea to Jesus to save them from the plague. A setting of Audivi vocem (1420), from the Egerton Manuscript was compellingly fluent and, unusually for these works, its text had a strong narrative component which was communicated expressively. A Gaude Virgo (c.1450) from the Ritson Manuscript was surprising ‘slippery’ with regard to both harmony and rhythm: the vision of Christ’s ascension was made vivid by the rising brightness of treble and high tenor.

Very little of the music of John Pyamour (fl.c. 1418-26) is known so it was a treat to hear the composer’s Quam pulchra es (TTB) which combined complex overlapping lines, a prevailing low register and textural clarity. The Tota pulchra es by Forest (fl.c. 1415-30) was followed by the beautiful cantilena motet of John Plummer (1410-84), Anna mater matris Christi, which was characterised by the irregularities and quirks of the earlier medieval period. John Trouleffe (fl.1448-1473) was associated with Exeter Cathedral; his Nesciens mater (TTB) is found in Ritson’s Manuscript and was sung here with extraordinarily rich colour, vibrancy and excellent ensemble spirit.

The Eton Choir-book supplied the final item: Stella celi by Walter Lambe (c. 1450/51-1504), a four-part setting which presents a plea from deliverance from illness - a reminder of the precariousness of fifteenth-century life. Lambe’s setting is elaborate and brings the four voices together in sustained imitative fashion - a fitting culmination to a splendid concert.

Poised but relaxed, the Orlando Consort conveyed a sense of respect for the idiom and a true appreciation of style, but also draw forth the ‘human’ quality of the music, connecting us to the musicians of the past.

Claire Seymour

The Secrets of Heaven : Orlando Consort (Matthew Venner - alto, Mark Dobell - tenor, Angus Smith -tenor, Donald Greig -bass)

John Dunstaple - Veni sancte spiritus/Veni creator spiritus; Anon - Alleluia. Christo iubilemus, O sponsa Dei electa, Kyrie-Cuthberte prece; Leonel Power - Gloria; Bittering - En Katerine solennia; Roy Henry - Sanctus; Anon - Second Fountains Abbey Manuscript, Cred; Dunstaple -Quam pulchra es, Descendi in ortum meum; Anon- Trent Codices, Stella celi; John Pyamour -Quam pulcra es; Forest - Tota pulcra es; John Plummer - Anna mater matris Christi; Anon - Egerton Manuscript, Audivi vocem and Ritson Manuscript , Gaude virgo; John Trouluffe - Nesciens mater; Walter Lambe - Stella celi.

Wigmore Hall, London; Thursday 25th April 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Orlando%20Consort.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Secrets of Heaven: The Orlando Consort at Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: The Orlando ConsortApril 27, 2019

Carlo Diacono: L’Alpino

Until quite recently and especially during the 18th, 19th and for half of the 20th century, the practice of symphonic music performance was almost non-existent in Malta. Consequently, Maltese composers of those times could never develop their professional activity in the symphonic field.

Since Monteverdi until the end of the 19th century, a composer seeking to establish a name in the profession was practically “obliged” to write opera - the genre par excellence which could show the technical and artistic mastery of composition. Thus, for Carlo Diacono (1876-1942), it must have been an absolute necessity to tackle and master this genre. This would not only enhance his already existing renommé as an exceptional composer, but also be the opportunity to live this artistic experience – the Mount Everest for almost every major composer in European music history over the centuries.

In 1903 Pope Pius X decreed the Motu Proprio regarding sacred music in churches.. This decision was intended to stop the vulgar and profane aesthetic tastes and habits that had slowly infiltrated sacred music through the years. Basically, the Motu Proprio aimed at obliging composers to produce sacred music in a kind of Palestrina style. Despite being maybe a necessary and healthy intention, this “cleansing” of sacred music created a new problem in Malta. As symphonic performance was non-existent in Malta, talented composers could only develop their art either as church composers within the restrictive parameters of the Motu Proprio or in opera, which for a Maltese composer would have been an extremely rare opportunity. One understands the seriousness of this drastic situation when one realizes that the Motu Proprio was declared in the same epoch when European art and music in particular was literally exploding with the creativity of such composers as Debussy, Mahler, Schoenberg, Webern, Berg, Ravel, Satie, Sibelius and later of Bartok, Stravinsky, etc.

With L’Alpino, Diacono was finally able to write an extensive work free of the yoke of the Motu Proprio, that is, with all his creative fantasy burning within him. Thus, L’Alpino enables us to have a clearer understanding of Diacono’s authentic artistic and creative talents without the limits of a rather old-fashioned system already “depassé” imposed by the church.

The resulting work speaks for itself. L’Alpino not only demonstrates Diacono’s obvious exceptional talent, but that with this first (and sadly last, since his later projects were left unfinished) attempt at writing an opera, he created a work of quite exceptional quality. We also realize that despite the isolation of Malta from artistic revolutions that were occurring on the continent, Diacono was still able to build on the relatively limited references he had of the genre - those operas that were produced at the Royal Opera House in Valletta. In fact, L’Alpino shows clear relations with the Giovane Scuola/Verism trends as regards both musical language, as well as treatment of certain formal elements - a contemporary theme from actual life, a tragic death of the heroine, an Intermezzo, the choir singing in a Church just before the fatal tragic fall-out on the church piazza...

The vocal writing is obviously very Italian and the work is rich in beautiful melodic moments. A very strong orchestral presence of quite elaborate harmonic development often leads the melodic discourse around the declamations of the singers’ lines. Diacono’s language is predominantly 19th century, but it seems that some more recent influences are incorporated, such as the use of the whole-tone scale as well as more ambiguous and chromatic harmony. It should be remembered that all the composers of the last part the 19th century were in one way or another infused by Wagner’s genius. In his way, Diacono makes use of an intricate system of “leitmotifs” which gives the 3 act opera a strong sense of compactness and unity.

L’Alpino reveals a strong symphonic intuition that elaborates primary material into an organic unified work from the first opening chords, developing towards a conclusion. From the beginning of the opera in the first act, Diacono establishes a number of themes, which constitute the main motifs. The opening Maestoso theme seems to evoke the epic landscape within which evolve the more personal and intimate actions of various characters. Among the other themes one finds Nella’s beautiful lyrical motif singing upon interesting harmonic sequences, also associated her love for Enzo. Another lyrical motif is associated with her mother Anna Rosa while the more negative traits of Franz the foster father and Andrea, the spurned lover are evoked by insidious chromatic motif.

Naturally these motifs are not only heard when characters associated with them, are singing. In fact, the more “arioso” moments often carry new and different material. However these main motifs seem to emerge regularly even in their absence, while other characters or situations are somehow evoking them, or when the composer seems to wish to remind us of some dramatic intention, a memory associated with a character or an event related to them. What is more interesting, however, is the way Diacono treats these motifs symphonically, changing their musical character according to dramatic context. Like characters of a novel or play, that develop and change, throughout the unfolding of the story, so do these musical motifs, meeting with and against each other and developing according to the needs dramatic discourse and situations. It seems to me that the first act is actually a symphonic movement with voices. Though the construction is quite free, one can almost define an exposition, a secondary section (arioso and chorus) a third section where the four themes (among other material) are quite intricately developed building towards a conclusion which reminds us of the first two main themes, this time metamorphosed with quite emphatic pathos.

The second act has a more narrative structure linked with the evolving drama, and the material is less symphonically developed. In spite of this, Diacono still uses thematic development of main motifs to maintain the architectural sense of the whole work. In a moment of high drama (when Franz and Andrea are trying to convince Nella to accept Andrea and threatening her to forget Enzo), Diacono builds the tension of this scene on the first main theme, which from its original initial epic character, here takes a very dramatic turn. Apart from serving as material for this scene, the reappearance of the theme, albeit metamorphosed, creates a new reference point with thematic elements of the first act. Diacono’s efforts towards structure may be further witnessed in the second act as one notices similar reappearances of main motifs (in different variants) after new musical material is presented and significantly, before the increasingly frequent interventions of the choir. As a result, the final tutti ensemble of soloists, choir and full orchestra finishes off the second act with a cathartic sense of deliverance and hope resulting from the preceding dramatic turbulence.

The Intermezzo opening the 3rd seems to have been added at some later. If it was indeed added, one could attribute this inclusion to Cavalleria Rusticana’s strong influence on contemporary opera composers (including Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov!). However, there may have also been technical and artistic requirements for Diacono to write this jewel of Maltese orchestral music. Not only are we presented with motifs and melodies still to come in the third act, but Diacono, here as well, metamorphoses a melodic element from a Nella /Anna Rosa duet in the second act into a dramatic crescendo leading us into an passionate explosion of the first main theme as climax. This Intermezzo takes us into a world of calm and melodic beauty after the maestoso tutti finale of the second act and also acts as a real bridge by reminding us of thematic motifs. It guides our appreciation of the work as a whole unit, which develops organically from the beginning of the first act by the end of opera.

As with the 2nd act, the 3rd act reveals less symphonic development within

itself.

New contrasting material is here juxtaposed and interspersed with purely

orchestral excerpts accompanying the movement of the crowd, the marriage,

the moment of the murdering shot and the confusion after the fatal moment.

However, when viewing the opera as a whole work, one notices that

Diacono’s regular use of main leitmotifs help us follow the dramatic

action, while also creating references in the listener’s memory

enhancing the feeling of structured development. Naturally, such structure

also depends on the relation of contrasting elements. An interesting

example is when Andrea is preparing to fulfill his tragic revenge. We are

presented with the theme of the most serene, intimate and somewhat

sentimental quality (which we had already heard in Intermezzo) which

creates an absolute contrast to the Andrea’s state of mind and

ominous words about death. This also offers opportunities to an acting

singer to develop Andrea’s complex character more deeply.

The choir’s interventions accompany the development of events in moments of light song, patriotic exclamations and more significantly while singing in sacred style during the marriage in the church. Diacono here seems to remind us somewhat of his profession as Maestro di Cappella, since this specific music scene evokes in many ways, albeit in a free manner, church music according to the Motu Proprio.

After a series of scenes with new musical material, including an attractive song like melody very reminiscent of the epoch’s style accompanying the happy spouses and guests coming out of the church, one notes that the further we move towards the tragic end of the opera, the more frequent do the main motifs that we discovered in the preceding acts reappear. They seem to interact and confront each other with more urgency. One example occurs during the singing religious music in church with the “negative” theme of Franz and Andrea intervening into the sacred chorale as Andrea is seen preparing to murder Enzo. Later, while Nella is dying, the material is almost entirely built on these key motifs, appearing one after the other, decorated in different colours and character. One seems to be replaced by another in an almost liquid manner, thus again creating a continuous musical discourse between themselves.

Here, the composer recalls the love duet of the first act, naturally transformed into the painful moment of Nella’s death. Again, we notice Diacono’s attention to musical structured form throughout the entire work. As the first act closes with the two main motifs of ecstatic character, so does the opera conclude, albeit with a different variant of Nella’s and Enzo’s love motif, this time transformed thanks to the whole tone harmonies into a passionate heart-rending cry. In a certain sense, the conclusion of the work expresses the tragic outcome in a dramatic way through the use of the main motifs that constituted most of the first act.

As its title says, this is indeed a melodramma in the best tradition of Italian opera, on the one hand definitely appertaining to Verismo, while at the same time related with more traditional patriotic evocation of Verdian notions – a work, that although was the composer’s first attempt in the art of opera, testifies not only to his general mastery of composition and dramatic theatrical talent, but also to a powerful symphonic intuition. With this flair, Diacono succeeds on making the listener remain emotionally involved in the teatralo-literary process and also involved in the purely musical development. This he manages to do without major technical breakthroughs and without relying on material effects. Diacono still believes in the potential expressiveness of sound itself, as is manifested by melody, harmony and organic counterpoint. He organizes all this with a creative structural sense, which though free and flexible, still creates a sense of extensive unity. This is why, as in all his works, using very simple and devoid of spectacular superficial means, he manages to convince the listener to follow him and join him in the journey, eager to hear what is to happen till the logical conclusion of the entire musical process.

Brian Schembri La Frette sur Seine 6.05.2018

Published courtesy of the Beland Music Society, Zejtun, Malta.

Click here for additional information regarding L’Alpino and Carlo Diacono.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Diacono.png image_description=Carlo Diacono product=yes product_title=Carlo Diacono: L’Alpino product_by=By Brian Schembri courtesy of the Beland Music Society, Zejtun, Malta product_id=Above: Carlo DiaconoManitoba Opera: The Barber of Seville

The company last presented the 203-year old opera buffa in November 2010, with its newest incarnation stage directed by Montreal’s Alain Gauthier for its three performances held on April 6th, 9th, and 12th. The 185-minute production (including intermission) boasted a strong cast of five principals with Tyrone Paterson leading the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra with his customary finesse.

Based on Cesare Sterbini’s Italian libretto, the production now transplanted from the 1800s to early 20th century Seville is admittedly plot-shy, relying rather on its stable of colourful characters painted in broad brushstrokes to bring its narrative to life.

First up is Figaro, with internationally renowned Canadian lyric baritone Elliot Madore’s dazzling MO debut as the tall, dark and strapping barber exuding conviction and swaggering ease every time he took the stage during the April 6th opening night performance, his booming vocals that filled the hall matched only by his flashing kilowatt smile.

Andrea Hill (Rosina), Elliot Madore (Figaro), and Steven Condy (Dr. Bartolo) [Photo by R. Tinker]

Andrea Hill (Rosina), Elliot Madore (Figaro), and Steven Condy (Dr. Bartolo) [Photo by R. Tinker]

He nearly stopped the show with his Act I entrance aria, “Largo al Factotum”, receiving prolonged applause with cries of bravo for his performance that only gathered momentum until his final, enthralling burst of tongue-twisting patter spat out with razor-sharp precision. It is hoped that the Toronto-born dynamo, who has also graced such illustrious opera houses as Metropolitan Opera, San Francisco Opera, Zurich Opera House, Glyndebourne Festival Opera and Bavarian State Opera, among others, will return to the MO stage again – and soon.

Canadian mezzo-soprano Andrea Hill (MO debut) reprising her role of Rosina from Calgary Opera’s November 2017 production, also directed by Gauthier, instilled flesh-and-blood nuance into her all-too-human character, her growing exasperation at being shuttered away by Bartolo palpable.

Her opening cavatina “Una voce poca fa” immediately displayed her full palette of tonal colours, including a shimmering upper register and warmly burnished tones in her lower range. It also provided the first taste of her sparkling colouratura, as she nimbly scaled vocal heights with quicksilver runs, later heard as well during duet “Dunque io son...tu non m'inganni?” sung with Figaro.

Like Madore, Hill is also a crackerjack actor, possessing a flawless comedic timing that includes furiously plucking flower petals in rhythm during her colouratura passages, and mugging and mocking Bartolo during the Act II “lesson scene” that elicited open guffaws from the crowd.

American tenor Andrew Owens (MO debut) as Count Almaviva - first appearing as poor student Lindoro – admittedly had a tough act to follow with his own opening cavatina, “Ecco, ridente in cielo” performed in the riptide of Winnipeg baritone David Watson’s servant Fiorello (also doubling as the Notary), with the latter’s earth-shaking vocals always seeming a force of nature.

Nevertheless, despite a few minor intonation issues and balance issues with the orchestra that quickly settled, Owen’s supple voice as a true Rossini leggero tenor proved its expressive best during “Se il mio nome saper voi bramate”, accompanied by Figaro’s mimed guitar accompaniment, and sung with elegant grace.

American baritone Steven Condy (MO debut) created an imperious Dr. Bartolo who bellows orders to his charge, also not afraid to let his own hair down when warbling during his own number in falsetto after taking over from Rosina’s “The Useless Precaution” during her singing lesson. His “A un dottor della mia sorte” that ends with his own crisply executed patter did not disappoint, equally straddling both worlds of hilarity and threatening power that also fascinated.

Canadian bass-baritone Giles Tomkins likewise brought dramatic intensity to his role as Don Basilio, Rosina’s vocal tutor and ostensibly Bartolo’s slimy sidekick. His performance of Act I’s “slander” aria, “La calunnia” with its famous long crescendo in which he advises Bartolo to smear Count Almaviva’s name became an early highlight.

Special mention must be made of Winnipeg soprano Andrea Lett who threw herself into her role as whiskey-swilling, cigarette-puffing maid Berta. Her heart-wrenching Act II aria “Il vecchiotto cerca moglie” in which she reveals her fear of growing old without love became the opera’s poignant underbelly and sober second thought, sung with artful compassion.

Gauthier – who also directed MO”s production of Verdi’s La Traviata in November 2017 – wisely allows his cast to venture off-leash as the show progresses with the well-staged production (albeit a trifle “park ‘n’ bark” at times) eliciting frequent hoots of laughter from the crowd.

One of the comic highlights (naturally) included the lesson scene, with Almaviva, now disguised as mop-topped singing teacher Don Alonso appearing to channel the wacky spirit of Victor Borge complete with “air harpsichord” effects.

The highly stylized Art-Deco flavoured set originally designed by Ken MacDonald for Pacific Opera Victoria, evokes the swoops and angles of Spanish surrealist painter Salvador Dali, instilling a dreamlike atmosphere further heightened by Winnipeg lighting designer Bill Williams’s shifting rainbow of pastel hues, with all costumes designed by Dana Osborne, also for POV.

A recurring visual leitmotif of umbrellas held aloft and twirled at strategic points (mostly) by an all-male Manitoba Opera Chorus (prepared by Tadeusz Biernacki) created fascinating counterpoint to the voices. Pure magic also arose during Act I’s final chorus “Mi par d'esser con la testa” when the policemen’s “bayonets” suddenly morph into brollies. However, despite the tightly synchronized choreography, this clever idea began to feel too much of a good thing as overly fussy stage business, pulling focus from the leads also gamely navigating their own rain gear props.

The first Act alone clocks in at 105 minutes, with several scenes, including extended recitatives between characters needing to be tightened further. Still, the production’s palpable joy delivered with gusto by a well-balanced cast made one long for their own well-coiffed Figaro, able to fix all of life’s woes with a swish of his wrist and gleam in his all-knowing, watchful eye.

Holly Harris

image=http://www.operatoday.com/MbOpera_BarberOfSeville_APRIL4_0564.png image_description=The Barber of Seville, Manitoba Opera, 2019. Photo: C. Corneau product=yes product_title=Manitoba Opera: The Barber of Seville product_by=A review by Holly Harris product_id=The Barber of Seville, Manitoba Opera, 2019. Photo by C. CorneauApril 26, 2019

Handel and the Rival Queens

In 1720s London, the ‘nightingales’ at war were Italian prima donnas Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni, represented at this London Handel Festival concert by Mary Bevan and Mhairi Lawson respectively, and supported by Christian Curnyn’s Early Opera Company. The performances of these eighteenth-century queens of the opera stage, at the Royal Academy of Music, led to mutual international renown. And, it was the story of their repute and rivalry which actress Lindsay Duncan recounted with telling dry wit at St John’s Smith Square, through excerpts from letters, diaries and newspaper reports interweaved between the arias which made the singers’ names in London and abroad.

To summarise the tale, Cuzzoni made her London debut in 1723, as Teofane in Handel’s Ottone at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket, a performance which caused a sensation. Many attested to her skill. German flautist-composer Johann Joachim Quantz appreciated her ‘tender and touching’ expression and the grace with which she embellished melodies. Charles Burney recorded that she ‘rendered pathetic whatever she sung’ and that her ability to control and adjust musical phrases with rubato made her a ‘complete mistress of her art.’ The Italian castrato Giovanni Mancini eulogised: ‘This woman possessed all the necessary requisites to be truly great. ... Her high tones were unequalled and perfect; intonation was born in her. She had an original and inventive mind ... and her choice of embellishments was something new. She left aside the usual and common and made her singing rare and wonderful.’

After Margherita Durastanti’s retirement, for two years Cuzzoni shared the London stage with the mezzosoprano castrato Senesino, an unchallenged prima donna. And, when Faustina Bordoni joined the Royal Academy in 1725, the management must have been delighted that her skills and qualities would complement those of Cuzzoni. A mezzo-soprano who excelled in rapid passagework, she was also a fine actress. The feisty roles which Handel would compose for Faustina were characterised by defiance, even aggression. One scholar has described the different attributes of the two singers thus: ‘Cuzzoni’s arias were often the pathetic sicilianos that showcased her expressive, cantabile singing. When in disguise, her characters masqueraded as shepherdesses, whereas Faustina’s characters disguised themselves only as men and warriors. The shepherdess had idyllic girlish qualities: she was innocent, pure, delicate, and coy. She inhabited the pastoral world. Faustina’s characters might angrily chastise male betrayers, but Cuzzoni’s only despaired and mourned in response to betrayal’. [1]

Faustina’s reputation preceded her to the English capital. As early as 30 th March 1723, the London Journal reported that ‘as soon as Cuzzoni’s time is out we are to have another over; for we are assured Faustina, the finest songstress at Venice, is invited, whose voice, they say, exceeds what we have already here.’

Quantz gave Burney an account of Faustina’s singing: ‘Faustina had a mezzo-soprano voice that was less dear than penetrating. […] Her execution was articulate and brilliant. She had a fluent tongue for pronouncing words rapidly and distinctly, and a flexible throat for divisions, with so beautiful a trill that she could put it in motion upon short notice just when she would. […] She sang adagios with great passion and expression, but was not equally successful if such deep sorrow were to be impressed on the hearer as might require dragging, sliding, or notes of syncopation and tempo rubato.’ Burney himself added that Faustina ‘invented a new kind of singing by running divisions with a neatness and velocity which astounded all who heard her. She had the art of sustaining a note longer, in the opinion of the public, than any other singer, by taking her breath imperceptibly. Her beats and trills were strong and rapid; her intonation perfect; and her professional perfections were enhanced by a beautiful face, a symmetric figure, though of small stature, and a countenance and gesture on the stage which indicated an entire intelligence of her part.’

The personal rivalry between the singers, stoked by their partisan supporters, was surely not what the Academy intended or desired, as this observation by Pier Francesco Tosi, an Italian castrato who taught in London in the late 1720s, suggests: ‘Their merit is superior to all praise; for with equal strength, though in different styles, they help to keep up the tottering profession from immediately falling into ruin. The one is inimitable for a privileged gift of singing, and enchanting the world with an astonishing felicity in executing difficulties with a brilliancy, I know not whether derived from nature or art, which pleases to excess. The delightful, soothing, cantabile of the other, joined to the sweetness of a fine voice, a perfect intonation, a strictness of time, and the rarest productions of genius in her embellishment, are qualifications as peculiar and uncommon as they are difficult to be imitated. The pathos of the one and the rapidity of the other are distinctly characteristic. What a beautiful mixture it would be, if the excellencies of these two angelic beings could be united in a single individual.’

Mary Bevan. Photo credit: Victoria Cadisch.

Mary Bevan. Photo credit: Victoria Cadisch.

The behaviour of the two operatic queens was far from ‘angelic’, however. It’s reported that at Cuzzoni’s first rehearsal with Handel she refused to sing ‘Falsa imagine’ from Ottone, as it had been written for Durastini; whereupon Handel called her a “veritable devil”, picked her up and threatened to throw her out of the window. Opposing camps of influential supporters quickly formed vociferous ranks: on Cuzzoni’s side were Lady Pembroke and Lady Walpole; leading the Faustina camp were Sir Robert Walpole, Lady Cowper, Lady Delaware and the Countess of Burlington. Race-horses were named after them; ‘Cuzzoni’ and ‘Faustina’ ran against each other at Newmarket. Lord John Hervey wrote: ‘In short, the whole world is gone mad upon this dispute. No Cuzzonist will go to a tavern with a Faustinian. And the ladies of one party have scratched those of the other out of their lists of visits.’

The incident most often cited as evidence of the divas’ cattiness is a scandalous hair-pulling fist-fight that erupted during a performance of Bonocini’s Astianatte in 1727. The London Journal reported restrainedly, on 10 June, that ‘A great disturbance happened at the opera, occasioned by the partisans of the two celebrated rival ladies, Cuzzoni and Faustina. The contention at first was only carried on by hissing on one side and clapping on the other, but proceeded at length to the melodious use of cat-calls and other accompaniments, which manifested the zeal and politeness of that illustrious assembly’. Dr John Arbuthnot was more graphic in his account, The devil to pay at St. James’s: ‘But who would have thought the Infection should reach the Hay-Market, and inspire two Singing Ladies to pull each other’s coiffs? ... It is certainly an apparent Shame that two such well bred Ladies should call Bitch and Whore, should scold and fight like any Billingsgate.’ [2]

Duncan told an entertaining tale - and I hope that Opera Today readers will indulge my rather lengthy summary - but the musical illustration of this historical vocal posing and posturing was less engaging. This was in no way a reflection on the undoubted talents and flair of Bevan and Lawson; nor the lively buoyancy of the EOC’s accompaniment and their spirited rendition of overtures from Handel’sOttone, Alessandro and Admeto, and Porpora’s Polifemo. But, the sequence of arias represented the dying days of the Academy, and simply did not offer sufficient contrast, character and inspired creativity to sustain the narrative, no matter how precipitously Curnyn commenced the musical numbers, sometimes almost interrupting Duncan’s spoken text.

Bevan and Lawson had the challenge of summoning characters with immediacy and removed from the dramatic context. When Handel’s music works its magic, as in ‘Che sento? Se pietà’ from Giulio Cesare the drama flowed; here, Bevan’s pianissimo decorative ascents in the da capo were brilliantly executed, and lyricism and theatre were nicely balanced. The first half of the programme focused on Alessandro and the eponymous protagonist’s marital woes, as two wives fought for his love. Lawson’s account of Rossane’s ‘Lusinghe più care’ was countered by Bevan’s lilting rendition of Lisaura’s ‘Che tirannia d’Amor!’, which exploited Cuzzoni’s trademark siciliana silkiness, and showcased Bevan’s range and poise. ‘Brilla nell’alma’ from the same opera was designed to show off Faustina’s coloratura pyrotechnics but while Lawson was light, agile and precise, there was almost too much gracefulness - sparkle but not true fieriness.

Mhairi Lawson. Photo credit: Lloyd Smith Photography.

Mhairi Lawson. Photo credit: Lloyd Smith Photography.

There were other operatic dramas that might have been more vigorously and viscerally brought to life. In Admeto, the wife and former lover - Alceste (Faustina) and Antigona (Cuzzoni) respectively - fight over the dying King Admetus of Thessaly, but here we had only the overture. In Siroe, re di Persia Handel pitted Emira - the daughter of Asbite, King of Cambaya, and Siroe’s lover (Bordoni) - against Laodice, Cosroe’s mistress and Arasse’s sister (Cuzzoni) (the plot’s the usual seria cat’s- cradle), but here we had only one aria, ‘Torrente cresciuto’ in which Bevan deployed her glossy soprano to full effect and essayed some coloratura panache in the da capo.

We also had arias from Porpora’s Arianna in Nasso (‘Miseri sventurati, poveri affetti miei’/Cuzzoni) and Hasse’s Cleofide (‘Qual tempesta d’affetti … Son qual misera colomba’/Faustina); in the former Bevan’s intonation and security were impressive as the vocal line leapt impetuously; in the latter, the EOC Orchestra supplied welcome dynamism, while Lawson waltzed through the voice-twisters with ease. But, if we haven’t heard such operas often in the past two three hundred years, there’s probably good reason. That said, there were plentiful musical treats, such as the lovely oboe obbligato in Faustina’s ‘Quell’innocente, afflitto core’ from Riccardo Primo, Rè D’Inghilterra.

One couldn’t fault the musicianship and the SJSS audience seemed delighted to have been beguilingly entertained and educated. But, there was a distinct lack of diversity and drama, given the theatrical exuberance of the feted queens whose exploits on and off the stage were here celebrated.

Claire Seymour

Handel and the Rival Queens : Early Opera Company

Mhairi Lawson (Faustina Bordoni), Mary Bevan (Francesca Cuzzoni), Lindsay Duncan (Narrator), Christian Curnyn (Director)

Handel - Overture to Ottone HWV15, ‘Spietati, io vi giurai ( Rodelinda HWV19), ‘Che sento? … Se pietà’ (Giulio Cesare HWV17), Overture to Alessandro HWV21, ‘Lusinghe più care … Che tirannia d’Amor!’ (Alessandro), ‘Brilla nell’alma ( Alessandro), Overture to Admeto HWV22, ‘Torrente cresciuto (Siroe, re di Persia HWV24), ‘Quell’innocente, afflitto core (Riccardo primo, re d’Inghilterra HWV23); Porpora - Overture to Polifemo, ‘Miseri sventurati, poveri affetti miei ( Arianna in Nasso); Hasse - ‘Qual tempest d’affetti … Son qual misera colomba’ (Cleofide)’; Handel - ‘Placa l’alma, quieta il petto!’ (Alessandro).

St John’s Smith Square, London; 24th April 2019.

[1] Wier, C.R. (2010) ‘A nest of nightingales: Cuzzoni and Senesino at Handel’s Royal Academy of Music’, Theatre Survey 51(2): 247-73.

[2] See Wierzbicki, J. (2001). ‘Dethroning the Divas: Satire Directed at Cuzzoni and Faustina’. The Opera Quarterly, 17(2), 175-96.

Britten's Billy Budd at the Royal Opera House

Director Deborah Warner, whose production of Billy Budd (a co-production with Madrid’s Teatro Real and Rome Opera) is the first for twenty years to grace the stage of the Royal Opera House, seems to be in accord with the views that Benjamin Britten expressed in a 1960 radio interview. For, it is Vere’s moral dilemma which dominates her interpretation. She makes no attempt to, as Britten’s librettist E.M. Forster put it in The Griffin in 1951, ‘tidy up Vere’: ‘We (Eric Crozier and I) have, you see, plumped for Billy as a hero and for Claggart as naturally depraved, and we have ventured to tidy up Vere’. In Warner’s production, Toby Spence’s Vere is undoubtedly “lost on the infinite sea”.

Michael Levine’s quasi-abstract design and Jean Kalman’s atmospheric lighting emphasise this. The sea is metaphoric. Forster had written to Britten, with striking prescience, ‘I will not recall you to the sea. Much as I love it, I believe that you ought to postpone it until you can create an old-man’s sea. Anyhow much later in your career’. [1] Here, platforms rise and fall (presumably intermittently obstructing the view of those seated in the upper ‘decks’ of the House) and the sea is evoked only by a trough of water across the centre of the stage (again, presumably not visible to patrons in the stalls) through which shipmen stomp and splash, to little evident purpose - Alasdair Elliott’s Squeak seems particularly partial to a paddle. Although there are nautical emblems, and we climb up to the mizzen-top and down into the ship’s underbelly, Levine and Warner make us imagine the expanse of ocean on which The Indomitable drifts and we sail instead through the mists and tidal surges of a psychological seascape. As Britten’s designer, John Piper, had urged, ‘We must never forget that the whole thing is taking place in Vere’s mind, and is being recalled by him”. [2]

The criss-cross of ropes, rigging and ladders that pattern the ROH stage suggest not just the regimented discipline of naval life but the net which entraps Vere, Claggart and Budd - even the Novice, who laments, “Oh, why was I ever born? Why? It’s fate, it’s fate. I’ve no choice. Everything’s fate.” And, Vere might plead, “O for the light, the clear light of Heaven”, but Kalman’s hazy, grey hinterland offers no illumination. We are adrift. The costumes, too, blur and confuse: if the design evokes a late eighteenth-century frigate, then Chloé Obolensky’s naval uniforms refer to the Second World War, and I’m not sure what is gained by simultaneously intimating ‘modern’ times and post-Revolutionary France.

Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Moreover, although Kim Brandstrup deftly choreographs the crew’s work and leisure - the ROH Chorus, who sang with stirring passion, are supplemented a thirty-strong group of actors - there is little sense of actual ‘movement’. In the opening moments, the sailors’ work-cry, “O heave! O heave away”, sees them on their knees, scouring the deck with holystones rather than tugging the ropes and rigging. They remain unmoved by Billy’s rallying summons, “Sway!”, and there is no sense of the integrative force that binds the men and which later erupts during the pursuit of the French frigate - here, despite the surging violence in the score, an episode which fails to evoke vigorous anticipation of victory - and after Billy’s hanging, when the crew reprise his unintentionally seditious farewell to his former ship, The Rights O’ Man, the ‘heave’ motif returning as a mutinous, threatening undercurrent. Kalman’s lighting emphasises the motionlessness, confining Vere to his cabin and the men to their hammocks in the hull.

Toby Spence (Captain Vere), Thomas Oliemans (Mr Redburn) Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Toby Spence (Captain Vere), Thomas Oliemans (Mr Redburn) Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The homoerotic sub-currents of both Melville’s novella and Forster’s libretto remain submerged in Warner’s production, and it is the opera’s religious allegory which is brought to the fore. There’s no doubting the answer to Vere’s desperate questions in the Prologue: “Who has blessed me? Who has saved me?” Just as Warner, in interview, described Claggart as a “fallen angel”, so this Billy is unambiguously seraph-like. Forster noted (in The Griffin) that some critics had surmised that Billy’s ‘almost feminine beauty’ and ‘the absence of sexual convulsion at his hanging’ indicate that Melville intended him as a ‘priest-like saviour’, but while he professed to have striven to emphasise Billy’s masculinity and ‘adolescent roughness’, Forster couldn’t resist portraying Billy’s hanging as a Christ-like sacrifice. And, Warner follows his lead, most strikingly during the ‘hidden’ interview between Vere and Billy before the sentencing. For, though Britten and Forster followed Melville - ‘Beyond the communication of the sentence, what took place at this interview was never known.’ - in this production the interview does not take place behind locked doors. As the orchestral ‘interview chords’ unfold, Billy moves to the rear of Vere’s private quarters; when he is sent down into the hold by the conscience-wracked Vere, Billy places a palm on his Captain’s forehead - an unequivocal gesture of compassion and clemency. But, while scholars have essayed various affirmative interpretations of the chords’ exposition of the opera’s essential conflicts, their ‘meaning’ inevitably remains obscure, just as the secrets of the locked room surely must remain undisclosed. The power of the chords is emotional, not rational. As Vere himself says, “I must not too closely consider these mysteries. As mysteries let them remain.”

Clive Bailey (Dansker), Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Clive Bailey (Dansker), Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Toby Spence may look rather too youthful to embody the “old man who has experienced much” who presents himself before us in the Prologue - here an ‘aged’ double sat stage-left, scouring the deck, perhaps in an attempt to erase past ‘sins’ - but he captured Vere’s dreamy self-absorption and lack of self-knowledge, shaping phrases and text with care and insight. This Vere retreats from the realities of life aboard a war-ship to read philosophy in his bath-tub, hosts his officers in his cabin while attired in his dressing-gown, and rolls up the carpet to lie down so that he can enjoy the sound of his men singing in their hammocks below: “Where there is happiness there cannot be harm,” he declares, evading his crew’s discontent through self-delusion. Warner’s direction frequently pushed Spence to the rear of the stage, and his light tenor did not always carry with sufficient weight, though Britten’s scoring helped him in the more declamatory outbursts.

Indeed, this ‘Starry Vere’ seemed remarkably remote from his men. It’s hard to imagine that he would inspire loyalty and love of the intensity which drives Billy to vow, “I’ll look after you my best. I’d die for you - so would they all.” Introspection characterises Spence’s Vere; I was not convinced that he was, as Forster and Melville emphasise, ever aware of his duties as a ‘King’ aboard the Indomitable, the upholder of God’s laws, charged with maintaining cohesion and stability. Such professional responsibilities influence Vere’s actions during the trial scene, but Warner emphasises instead the personal dimension: the three officers - Flint (David Soar), Redburn (Thomas Oliemans) and Ratcliffe (Peter Kellner) seem both shocked and disappointed by Vere’s refusal to save Billy, and thus it is his personal anguish which is foregrounded, and separated from the pressures and tensions of life on-board a ‘floating prison’.