May 31, 2019

Lise Davidsen sings Wagner and Strauss

Besides her Norwegian roots, she shares with the distinguished Wagnerian soprano a warm, gold-flecked timbre and full, incandescent top notes. Hers is a Rolls-Royce among voices. Now in her early thirties, Davidsen’s schedule is already booked up with engagements at A-list opera houses. This is not the first record she appears on, but it is her debut solo album for Decca, with whom she has an exclusive contract. With two Wagner arias and familiar songs by Richard Strauss, the program contains no surprises, just Davidsen claiming the repertoire that is her birthright by virtue of her exceptional talent.

The recital opens with Elisabeth’s two arias from Wagner’s Tannhäuser, a role in which the soprano will make her Bayreuth debut this year. With big dramatic voices there is always the challenge of capturing their full breadth on recordings. It’s like trying to stuff a silk parachute into a matchbox. Climactic notes, such as at the conclusion of Dich, teure Halle, are indeed too resonant for mere living room speakers to handle. But, on the whole, the technical team has done an excellent job, beautifully preserving Davidsen’s velvety warmth. In Elizabeth’s prayer, she sustains the measured lines with no difficulty, but also evokes the pathos, if not the fragility, of this broken woman. Esa-Pekka Salonen and the Philharmonia Orchestra accompany her in Wagner with athletic vigor and in Strauss with bright, glinting colors, but this recital is all about the diva. If the Wagner excerpts hold the promise of memorable Elizabeths, Elsas and heavier roles such as Isolde, the sole Strauss aria, from Ariadne auf Naxos, benefits from Davidsen already having sung the role in staged productions, including ones at Glyndebourne and Aix en Provence. She sings Es gibt ein Reich sumptuously, but also with nuance and a tinge of melancholy that lingers. She brings the same gorgeous wistfulness to orchestrated songs by Strauss such as Ruhe, meine Seele! and Morgen. Meeting the narrative demands of Heimliche Aufforderung, Davidsen emerges as an intelligent painter of text, and her voice bursts effortlessly in the rapturous Cäcilie.

In Malven, the very last song Strauss composed, the voice is lightened against Wolfgang Rihm’s 2012 orchestration, which evokes summer flowers teased by the wind. There are several fine interpretations of Strauss’s Four Last Songs (technically, the last four but one), but this one joins the list of those most gorgeously sung. There is no register or hue in which Davidsen’s voice doesn’t ripple, glide and soar, making any voice-loving heart skip a beat or two. No doubt she will sing these songs of introspection and resignation many times and on many stages and her insight into them will deepen with age and experience. But, catching her in youthful opulent freshness, this transfixing account will demand to be played over and over again. In fact, the whole recording invites unabashed wallowing in a rare voice coupled with the communicative power of a true artist. So wallow away, and let’s hope that, even though the golden times of studio recordings are long gone, this will be one of many tracking the path of this golden voice.

Jenny Camilleri

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Davidsen.png image_description=Decca 4834883 product=yes product_title=Lise Davidsen sings Wagner and Strauss product_by=Lise Davidsen (soprano), Esa-Pekka Salonen (conductor), Zsolt-Tihamér Visontay (violin), Philharmonia Orchestra product_id=Decca 4834883 [CD] price=$12.59 product_url=https://amzn.to/2WfeIJFNicky Spence and Julius Drake record The Diary of One Who Disappeared

He and pianist Julius Drake are evocative storytellers in this unsettling tale of desire and doom. Janáček himself was in the grip of romantic obsession when he composed the Diary, the first of several works inspired by Kamila Stösslová, whom he met in 1917. Almost forty years younger and married, Stösslová neither fanned nor spurned Janáček’s attentions. As his muse, she inspired characters in his operas Káťa Kabanová, The Cunning Little Vixen and The Makropoulos Affair. Zefka the gypsy was her first artistic incarnation. As per Janáček’s instructions, she was the model for the woman on the front cover of the published score. The text, anonymous poems that appeared in a Brno newspaper, is scored for tenor, mezzo-soprano, piano and a small choir.

Spence, who has performed Janáček on the operatic stage, is eminently at home in the composer’s distinctive vocal writing, with its speech-like cadences and folk music lineage. His delivery is immediate, as if he’s confiding to a sympathetic listener. In an emotionally layered portrayal, his hero falls in love with sweet head tones. His fate is sealed when Zefka proffers to show him “how gypsy people sleep”. At the moment of surrender, Spence, sounding dazed, pares down his voice to a sliver of resigned sadness. Later on, he projects mordant self-hatred as the young man realizes he has fallen for someone he considers his social inferior – the undertone of violence is palpable. Mezzo-soprano Václava Housková avoids crass earthiness, giving the folky lilt of her siren call a youthful guilelessness. The offstage female chorus, recorded with a pronounced reverb, surrounds her with eerie echoes, evoking the almost supernatural role that destiny plays in this work. “Who can escape his fate?”, asks the troubled hero. Drake gives an unequivocal answer in the Intermezzo erotico, with its tattered rhythms and final, plummeting 32nd notes. Like the beautiful Zefka, Drake’s piano playing is ravishing and tenacious, with assertive coloring that leaves the harmonies transparent. Dissonances are forceful without ever sounding ugly. After Spence’s anguished, closing top Cs, there can be no doubt about the protagonist’s unhappy future. This performance was recorded at All Saints’ Church in East Finchley, London. Piano and solo voices are encircled with space, but sound close enough to preserve intimacy.

The second half-hour of the recording is more cheerful. The choir sings the first version of Říkadla (Rhymes), eight nursery rhymes for one to three voices, clarinet and piano. (In the later, definitive version, Janáček more than doubled the number of songs, scoring them for chamber choir and ten instruments.) Drake and clarinetist Victoria Samek accompany the charmingly nonsensical words with a sparkling sense of fun. This time, the reverb around the singing trio is obtrusive, giving them a disembodied quality that jars with the material. Spence and Housková feature again in the last set, twelve selections from Moravian folk poetry in songs. These folk tune arrangements, a mix of wistful ballads, love songs and brisk dances, illuminate the influence of traditional music on Janáček’s idiom. They are also utterly captivating. Housková interprets them with endearing simplicity, like someone sharing native songs learned in childhood. Spence’s approach is a tad more operatic. He shades the words with a feather-light touch, suggesting a sigh on a diminuendo, or an increasing heartbeat on a rising phrase. The recital ends with a foot-tapping duet, a party number called Musicians. For those who feel like singing along, the accompanying booklet contains the original poems in Czech, with English rhyming translations. Texts in Czech and English translations are also included for The Diary of One Who Disappeared and the nursery rhymes.

Jenny Camilleri

image=http://www.operatoday.com/CDA68282.png image_description=Hyperion CDA68282 product=yes product_title=Leoš Janáček: The Diary of One Who Disappeared product_by=Nicky Spence (tenor), Julius Drake (piano), Véclava Housková (mezzo-soprano), Voice Vocal Trio, Victoria Samek (clarinet) product_id=Hyperion CDA68282 [CD] price=$16.99 product_url=https://amzn.to/2YYC17gMay 29, 2019

Time Stands Still: L'Arpeggiata at Wigmore Hall

Music for a While similarly brought the Baroque into relaxed conversation with jazz, folk and world music; La dama d’Aragó homed in on songs and dances from Catalonia and Mallorca. More recently, in Himmelsmusik , L’Arpeggiata explored connections between the seventeenth-century German and Italian traditions, as German traditions of counterpoint and chorale were both sustained and developed, while also integrating Italian innovations such as poly-choral antiphony and solo song.

Time Stands Still , presented last night at Wigmore Hall, was a rather curious affair, though. Even the title seemed paradoxical, as Alexandra Coghlan points out in her programme article: ‘it’s a concert of musical change and evolution, tracing the shifts, twists and turns of a century of social, political and aesthetic upheaval for the British Isles’. (Plus ça change, then …)

So, we started with a sequence celebrating the Art of Melancholy, as Dowland couched political complaint within romantic suffering. Then followed some sweetly soporific songs by Robert Johnson and John Bennet, while the latter part of the programme - performed without an interval, with several items segue, and lasting just over one hour - took us into the Jacobean alehouse for Broadside ballads and dances by John Playford et al. Purcell’s ‘Music for a While’ brought proceedings to a close, Dryden’s imagery of medicine, science and religion mingling with Purcell’s music to evoke the latter’s power. On paper, at least, it looked a bit of a musical menagerie.

The vocal items were sung by Belgian soprano Céline Scheen. Commenting on the above-mentioned Himmelmusik, I remarked the ‘purity’ of Scheen’s soprano, her ‘exquisite phrasing and carefully placed nuance’ which ‘perfectly captured the text’s spirit of tenderness and love’, her ‘crystalline tone, and considerable vocal agility’. All such attributes were again on display.

But, on the previous occasion I also felt that the ‘purity’ of the tone did not always serve the text well and wished for ‘greater variety of colour to complement and bring to the fore the textual inflections’. And, if the ‘sacred’ items of Himmelmusik were sometimes well served by Scheen’s angelic ethereality, then that wasn’t the case in Time Stands Still. Quite simply, the text - which allows the singer to communicate and the listener to understand the context - matters in these items: as much in Dowland as in a bawdy ballad. Both may hold covert meaning and messages. Both are powerfully ‘human’ in expression, whether employing and demonstrating a refined sensibility or more earthier energies.

Scheen had a heavy music book in her hands, often holding it quite high before her and peering closely; however, I could scarcely discern a single word of the texts she sang. Her soprano is beautiful, and it is pure: so much so that it seemed almost disembodied on this occasion. And, its pristineness is unblemished, never tainted by even the most tantalising dust-speck of colour. There is undoubtedly repertoire for which such a voice is ‘perfect’, but Dowland’s lute songs are not that repertoire.

A good singer of lute song needs not just a clear voice and flexibility in the upper range - both of which Scheen possesses - but also refined poetic understanding. For example, in ‘Sorrow stay’, the penultimate line, ‘But down, down, down I fall,’ embodies the poet-protagonist’s struggle and defeat, but Scheen’s distorted vowel (I seemed to hear two syllables on ‘down’) and changeless tone did not communicate this, as had Ian Bostridge , for example, with Elizabeth Kenny at Kings Place in 2014.

In ‘Time stands still’ and ‘Flow, my tears’ it was, paradoxically, only when the instrumentalists joined the song that human emotions breathed and flowed. The warmth of Doron Sherwin’s cornetto was a delight throughout the evening while Francesco Turrisi played the organ with imaginative and wry fingers, developing counterpoint, elaborating ornaments. In ‘Flow, my tears’, Pluhar was eloquent in her engagement with the voice. In ‘I saw my lady weep’ it as Sherwin - performing from memory throughout the recital - who exploited the chromatic nuances and rhythmic tangles and tugs.

Perhaps Scheen’s soprano was more suited to Robert Johnson’s ‘Care-charming sleep’ and John Bennet’s ‘Venus’s birds’ where the lovely clean sound was beguiling, and the words are designed to be cumulative in effect rather than deliberately pointed. But, when we reached the ‘traditional’ songs and ballads, the story-teller’s glee and mischief was sadly missing. It take a natural ‘actor’, one with a love of language that can be expressed through articulation and tone, to make lines such as the repeated ‘Hi diddle um come feed-al’ of ‘The Tailor and the Mouse’ come alive and feel rich, raw and rollicking. Though, it must be noted that Turrisi did a good job of conjuring the mouse’s scurrying and fleeing from the tailor’s intent pursuit! Sherwin showed how it should be done in his forthright interjections in ‘The Frog and the Mouse’: now we had words, vibrancy and directness.

It was, in fact, the instrumental items that made the strongest impression. William Brade’s ‘Scottish Dance’ got my foot tapping as Sherwin pushed ‘freedom within constraints’ to its expressive peak, and Turrisi mimicked a brusque bag-pipe drone. Playford’s ‘Stanes Morris’ was similarly abandoned in its rhythmic fire, but never other than consummately controlled. The latter’s ‘Parson’s Farewell’ seemed to embody a neat ironic detachment, while in ‘Paul’s Steeple’ I loved the rhetorical confidence, even cheekiness, of Josep María Martí Duran’s baroque guitar as he explored timbre and texture with panache, while Turrisi brushed a tambourine with style.

We had an encore in which Morley’s ‘There was a lover and his lass’ morphed from madrigal to jazz improv, and Sherwin’s cornetto became Acker Bilk’s clarinet. But, such immediacy, invention and sheer fun wasn’t quite enough to overcome the preceding programme’s distance and detachment.

Claire Seymour

L’Arpeggiata: Céline Scheen (soprano), Francesco Turrisi (harpsichord, organ), Josep María Martí Duran (lute, baroque guitar), Doron Sherwin (cornet), Christina Pluhar (director, theorbo)

John Dowland - ‘Time stands still’, ‘Flow my tears’, ‘Sorrow, stay, lend true repentant tears’, Anthony Holborne - ‘The Image of Melancholy’; Dowland - ‘I saw my Lady weep’; Robert Johnson - ‘Care-charming sleep’, ‘Have you seen the bright lily grow?’; John Bennet - ‘Venus’ birds’; William Brade - Scottish Dance; Trad/English - ‘The Three Ravens’; John Playford - Stanes Morris; Trad/English - ‘The Tailor and the Mouse’; Playford - ‘Parson’s Farewell’; Trad/English - ‘The Oak and the Ash’; Playford - ‘Paul's Steeple’; Trad/English - ‘The Frog and the Mouse’; Henry Purcell - ‘Music for a while’.

Wigmore Hall, London; Tuesday 28th May 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/C%C3%A9line%20Scheen.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Time Stands Still: L’Arpeggiata at Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Céline ScheenPuccini’s Tosca at The Royal Opera House

One should at least be relieved that it’s set sometime during the 1800’s - and not in a carpark where a resurrected Scarpia returns in Act III to shoot Tosca as happens in Sturminger’s re-imagined production at Salzburg (shabby, and a shocker). When I reviewed this Covent Garden production back in January 2018, I seemed to view it more as one malevolent and cruel empire set against the backdrop of a city infected by poverty and moral decline. Andrew Sinclair’s revival seems a bit less focussed on this - or perhaps I simply couldn’t see it because what hasn’t changed is the simply unremitting darkness in which much of this production is set. I still think Paul Brown’s designs are largely impressive but what I noticed more this time was the imbalance of them. There is perhaps something askew when the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle in Act I lacked scale and Scarpia’s apartment at the Palazzo Farnese doesn’t. This is a church that often resembles a crypt, but it fits well with the oppressive feel of Act I where some are just nearer God and some are just unfortunate enough never to be.

Act II did seem a little less pallid this time which was just as well because it centred attention so much more neatly on the power struggle which is the centrepiece between Scarpia and Tosca. Act I in this production, despite all that is going on, still felt static; yet Act II never seemed constrained - though I think this largely had to do with the powerhouse performances of Terfel and Opolais who used every bit of the stage like warring tigers. One was perhaps a little more conscious of diversions, such as the opening and closing of window shutters (I really lost count of how many times that happened), but they prowled magnificently. Act III still seems problematic. I was more conscious than ever that it seemed back to front. Depending on where you sit in the stalls, the shooting posts have a tendency to block your view and the lighter this short act becomes the less it becomes visually convincing. As impressive as this particular immolation from Tosca might have been, one was still left with the impression she had simply flung herself off the end of a rather inconspicuous pier.

Vittorio Grigolo (Cavaradossi). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Vittorio Grigolo (Cavaradossi). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The shock value in this revival comes from the casting. The opening night audience clearly fell in love with Vittorio Grigòlo’s Cavaradossi. The role is a relatively recent one he has taken on, having made his debut with it at the Metropolitan Opera last year; I can’t help but feel somewhat equivocal about him. Joseph Calleja, who sang Cavaradossi in 2018 here, sounded rather small - Grigòlo is the exact opposite. His is not a voice to shy away from using its wide range, though what many might confuse as heft I’d rather describe as ungainliness. What is so frustrating about him is that there is such an undeniable originality he brings to his phrasing which, in part, is an extension of his quite remarkable acting. Okay, some might call it a little hammy, and certainly it stretches the boundaries of good taste relatively speaking, but just as his acting pushes limits so does his vocal characterisation of this part. If a tenor like Jonas Kaufmann is always pristine and rich in this role, Grigòlo cuts it with an unpolished legato and a roughness which seems much closer to Cavaradossi himself. He is really a little uncouth. But no one really falls in love with perfection, or even a remotely ideal personification of it. I’ve rarely heard a more visceral ‘Recondita Armonia’ but it did Grigòlo few favours because the voice was often at such full tilt it sometimes felt off-balance. Thrilling it might have been, but you also felt he was going to fall flat on his face (or, rather, off his scaffold). His acting during ‘E lucevan le stelle’ was enormously draining to watch - but at the same time compelling. Did one really care that the voice (again stretched at an unbelievably loud volume) fractured in places? Not one bit. He certainly has the ability to sing with restraint - this was notable in some of his duets - and he can scale the voice down when he wants to. But ultimately, this felt like a performance from a tenor who liked to live both in the fast lane and somewhat dangerously. A Cavaradossi who perhaps had parked his sportscar is Sturminger’s Salzburg carpark.

Kristine Opolais (Tosca). Photo credit:Catherine Ashmore.

Kristine Opolais (Tosca). Photo credit:Catherine Ashmore.

Kristine Opolais’s Tosca, on the other hand, seemed everything her Cavaradossi wasn’t. If he wobbled and seemed rough-hewn, she was like an empress with an ermine softness to her bottom register and a steely brilliance to her upper that never betrayed a hint of unsteadiness. I’ve never really noticed in many Tosca’s previously the underlying jealously that betrays her character in Act I but here Opolais was a real storyteller, unravelling her insecurity with touching sincerity and a little humour to pad it out. Some Tosca’s can - indeed do - seem very distant from their Cavaradossi but Opolais worked a beautiful chemistry with Grigòlo. But Tosca is a very complete role, one that requires a singer to be a great actress too and that is no more so that in the great Act II.

I suppose any Tosca today would be fortunate to have Bryn Terfel as her Scarpia and Opolais did not waste this opportunity. Perhaps because Terfel brings such sheer brutishness and malevolence to Scarpia, Opolais was formidable. The voice is just heavenly - those high notes were like jangling chains whipping against exposed flesh. But how rare to hear a ‘Vissi d’arte’ that was sung with so much reverence and depth to its inner meaning. So many sopranos sing this aria towards the audience; Opolais was bowed, penitent, the voice like an invocation. It made her killing of Scarpia all the more gruesome as she stabbed him not once, but twice, exposing his waistcoat so we could see his blood-soaked shirt.

Terfel’s Scarpia has lost nothing over the years. There are any number of things about his performance which still have the capacity to shock an audience. His stage presence is completely absolute, and you oddly feel he’s there when he really isn’t doing anything. His magnetism is beyond compelling. Terfel’s Scarpia is becoming very like Tito Gobbi’s - the snarling notes, the eyes that widen and glower with terrifying power, the stalking like a presumptive predator. When he unbuttons his waistcoat because he believes he has vanquished Tosca the shock he might actually rape her is quite real. The voice itself is a massive instrument, a hammer of Thor. What was so exquisite about this Act II - so completely compelling - was Terfel’s projection of the notes. Every nuance was there; it was simply astonishing.

What was also unquestionably better this time was the conducting of the score; Alexander Joel clearly knows his way through the treacherous terrain of Puccini’s music. There were moments when he felt the need to linger, or broaden his tempo - Act II was generally somewhat longer because of his tendency to just make it one long crescendo that suddenly collapses into final murderous resolution. He sometimes made Grigòlo’s more heroically-minded attempts at stage dominance more difficult by reigning him in, notably during ‘E lucevan le stelle’ which caused the tenor problems - but the opposite was the case during Grigòlo’s two cries of ‘Vittoria’ which pushed him into brinkmanship. The orchestral playing was glorious with beautiful string tone, and Joel evidently lavished attention to the brass playing; the horns at the opening of Act III were simply fabulous in both tone and precision.

This is a Tosca that still looks beautiful at times, though that beauty often means it looks somewhat gritty, perhaps even grungy in places. No amount of gold can make a crypt look ecclesiastical, and not even a star-lit sky can rescue a final act that looks like a couple of scrappy wooden posts beside a grey wall that, well, looks like a grey wall. This was an evening rescued by its singers - and in the case of Grigòlo’s Cavaradossi rather overshadowed by it. If Opolais and Terfel gave us a masterclass in great singing and acting, Grigòlo gave us something else. I came out of this undoubtedly interesting performance thinking I hadn’t really seen Puccini’s Tosca but a new opera called Puccini’s Cavaradossi.

From 30th May until 20th June 2019

Marc Bridle

Puccini: Tosca

Kristine Opolais (Tosca), Vittorio Grigòlo (Cavaradossi), Bryn Terfel (Scarpia), Hubert Francis (Spoletto), Jihoon Kim (Sciarrone), Michael Mofidian (Angelotti), Jonathan Lemalu (Sacristan); Jonathan Kent (director), Alexander Joel (conductor), Andrew Sinclair (revival director), Paul Brown (designer), Mark Henderson (lighting), Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 27th May 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Terfel%20as%20Scarpia.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Tosca: Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

product_by=A review by Marc Bridle

product_id=Above: Bryn Terfel (Scarpia)

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore

May 27, 2019

A life-affirming Vixen at the Royal Academy of Music

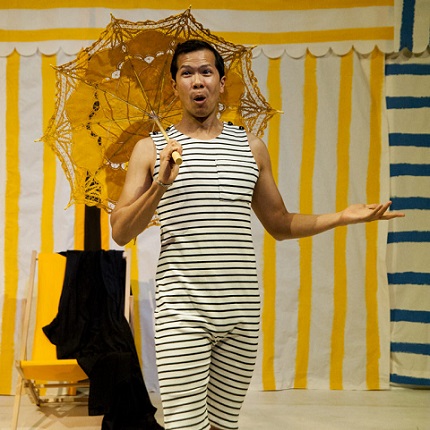

However, while Janáček’s opera is based upon a comic strip - its libretto being drawn from the narrative which Rudolf Tĕsnohlídek wrote to accompany illustrations by Stanislav Lolek which were published in the Brno newspaper, Lidové noviny - as we follow the story of the life and adventures of the eponymous vixen, it’s no child’s play for a director to balance the elements of pure fantasy with the opera’s underlying realism.

In this production for Royal Academy Opera, director Ashley Dean has decided that simplicity is a virtue: and, with considerable assistance from Kevin Treacy’s terrific lighting design and Laura Jane Stanfield’s panoply of fabulous costumes, he’s proved right.

Helen May (Woodpecker). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Helen May (Woodpecker). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Stanfield’s set comprises just a carpet of wood-chippings which creep a little way up a backdrop swathed in gradated washes of deep hues - indigo, ultramarine, emerald - the floods of colour powerfully evoking the forest milieu. A few props are carried in now and then, to indicate a change of locale: the hens roost on wooden chairs, the Schoolmaster and Priest grumble around tables in the inn. Treacy’s lighting makes the forest world by turns vivid and alive, nostalgic and restful, the colour drawing us into the animals’ world. In this way, the animals are not simply ‘symbols’, reflecting human flaws and frailties; rather, nature is truly present and real. A recollection by Janáček himself, of the process of composition, seems apposite: ‘It was odd how red fur continually gleamed before my eyes.’ Dean and movement director Christina Fulcher create a strong sense of ‘communities’: of a human society and an animal milieu. Most importantly, the interaction between them is persuasive.

In this regard, Stanfield’s incredibly detailed costumes also play large part. The above-mentioned Brno preview article tempted its readers with a description of the ‘seventy costumes’ designed by artist Eduard Milén which they would enjoy: grasshoppers and crickets would hop about in ‘yellow-green tailcoats and magnificent little wings’; nocturnal glow-worms would be equipped with reflectors ‘to light up their bottoms’; the ‘melancholy beauty’ of an iridescent dragonfly would be enhanced by the glittering gold of its fragile underwings.

Thomas Bennett (Badger). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Thomas Bennett (Badger). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Stanfield’s attention to detail is no less comprehensive or imaginative, and the results are beguiling as she brilliantly anthropomorphises the animal world. Hats, turbans, scarfs, shawls, feathers, fur, brocade: textures and colours dance before one’s eyes. The Cockerel struts like a Persian prince in golden boots and towering turban-crest; Badger is cloaked in a glorious grey fur coat, topped with a bandana-cum-bedcap; the hens shake their white petticoats and stamp about in marigold-stockings. The Vixen’s layers of red, orange and brown are both down-to-earth and feminine; the Fox strides confidently in his tall leather boots, but his shabby corduroy waistcoat speaks of a warm heart behind the pride. Cleverly, Stanfield manages to suggest both a rustic earthiness and a Victorian primness - adding piquancy, for example, to the scene where the animals peer into the Vixen’s underground den, spitting out their disapproval and outrage at her amorous activities with the Fox.

Samuel Kibble (Cock). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Samuel Kibble (Cock). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

As the action unfolds, the immediacy and realism of the drama is wonderfully blended with fantasy and fable. There is a winning directness in scenes such as the henhouse, where the Machiavellian Cock forces the hens to lay ever-bigger eggs to feed his capitalist greed, while they remain blind to their own subjugation. When he meets a swift end, a dupe of the Vixen’s ‘playing dead’, we are both shocked and satisfied. The Act 1 dance between the Frog and the drunken Mosquito (he’s bitten the inebriated Forester), and the dawn games and chatter of the animals in Act 2, are enchanting.

Peter Harris (Mosquito). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Peter Harris (Mosquito). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Having excelled in RAO’s recent productions of Semele and L’enfant et les sortilèges , here Lina Dambrauskaitė was a vivacious and tremendously engaging Vixen. Her soprano has a lovely freshness, but she also captured the Vixen’s strength and passion, as when she attacks the poacher Harašta or in her flirtation with the Fox, when she brags about her thievery and courage. Dambrauskaitė was well-partnered by Hazel Neighbour’s Fox, whose slightly heavier soprano shone richly against Dambrauskaitė’s brightness. Their love duet was a highpoint, but the revealed the gentle humour of their relationship too: there was a wicked glint in Fox’s eye as he glanced towards their den, wryly asking his Vixen, ‘How many children do we have? How many shall we have?’ (The opera was sung in Norman Tucker’s English translation.)

Lina Dambrauskaitė (Vixen) and Hazel Neighbour (Fox). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Lina Dambrauskaitė (Vixen) and Hazel Neighbour (Fox). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

As the Forester, James Geidt revealed a strong, true baritone which conveyed the gamekeeper’s inner emotions with conviction. Initially evincing a morose world-weariness, his growing feeling for the Vixen - evidenced in a vulnerable hesitancy with his gun, allowing her to escape - flourished into a compassion which was both touching and credible.

James Geidt (Forester). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

James Geidt (Forester). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The characterisation was consistently good. Peter Harris’s narration conveyed every ounce of the Schoolmaster’s pessimism, concluding with a laconic shrug of indifference. Thomas Bennett was an eloquent Priest; Niall Anderson displayed a powerful baritone as Harašta. Robert Forrest and Yuki Akimoto formed an effective pair as the Innkeeper and his wife. One can see why Vixen is attractive repertoire for the conservatoires. The cast is large thus allowing many students to take solo roles. Here they did so with aplomb, with Gabrielė Kupšytė’s Dog and Lorna McLean’s Chief Hen particularly noteworthy.

Niall Anderson (Poacher). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Niall Anderson (Poacher). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The death of the Vixen was truly shocking, in its suddenness, lack of mawkishness and finality. One moment the Vixen danced and taunted Harašta, free and invincible; the next she lay dead on the forest floor. The scenes of Janáček’s opera are rather episodic, and not connected in any linear or causal fashion, yet they seemed to have led inescapably to this moment. Subsequently, though, Dean struggled to maintain dramatic shape and momentum, and the final scenes drifted somewhat towards Geidt’s concluding reflections on the death of the Vixen and on his own mortality. This pantheistic creed was, however, beautifully sung, with warmth and flexibility: reconciled to life’s transience, the Forester was embraced by the beauty of forest.

Philip Sunderland conducted the Royal Academy Sinfonia in a crisp and rhythmically tight reading of the chamber arrangement of Janáček’s score made by Jonathan Dove. The dance episodes had real verve and lightness. But, while I can appreciate why this reduced scoring was used, with just five string players in the 18-strong ensemble the wind were overly dominant - at times it sounded more like Stravinsky - and while Sunderland maintained a clarity of texture which ensured that we could appreciate the details of harp, percussion and suchlike, I missed the surges of Romanticism in the orchestral episodes in which the lyricism communicates an emotional sensuousness to complement the leanness and realism elsewhere.

That said, if this production lacked a certain wistfulness, then the absence of sentimentality was welcome. Human weaknesses were exposed by their interaction with the animal world: such frailties were understood, accepted and forgiven. The Cunning Little Vixen meant so much to Janáček that he requested that the conclusion be played at his own funeral. This performance at the Royal Academy was both heart-warming and life-affirming.

Claire Seymour

Janáček (arr. Jonathan Dove): The Cunning Little Vixen

Vixen Sharp Ears - Lina Dambrauskaitė, Fox - Hazel Neighbour, Forester - James Geidt, Priest/Badger - Thomas Bennett, Schoolmaster/Mosquito - Peter Harris, Forester’s Wife - Clare Tunney, Pásek, the Innkeeper - Robert Forrest, Harašta, the poacher - Niall Anderson, The Innkeeper’s Wife - Yuki Akimoto, Dog - Gabrielė Kupšytė, Owl - Samantha Quillish, Cock Samuel Kibble, Chief Hen/Vixen Mother - Lorna McLean, Jay - Hope Lavelle, Woodpecker - Helen May, Pepík, the Forester’s son - Aimée Fisk, Frantík, the Forester’s son - Maya Colwell, Vixen Cub - Anna Mengel, Frog - Kathleen Nic Dhiarmada, Grasshopper - Ashleigh Charlton, Cricket - Jack Lee, Hens and Fox Cubs (Caroline Blair, Margaret Mitchell, Clara Lobo, Maria Ejderos Sveinungsen, Avital Green, Leah McCabe); Director - Ashley Dean, Conductor - Philip Sunderland, Designer - Laura Jane Stanfield, Lighting Designer - Kevin Treacy, Movement Director - Christina Fulcher, Royal Academy Sinfonia.

Susie Sainsbury Theatre, Royal Academy of Music, London; Friday 24 th May 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Fox%20and%20Vixen%20standing.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Cunning Little Vixen: Royal Academy Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Hazel Neighbour (Fox) and Lina Dambrauskaitė (Vixen)Photo credit: Robert Workman

May 24, 2019

Glyndebourne’s first production of Dialogues des Carmélites to open Glyndebourne Festival 2020

Sarah Hopwood, who joined Glyndebourne as Finance Director in 1997 and subsequently became Chief Operating Officer, spoke about the unique business model that allowed Glyndebourne to fund the Production Hub: ‘It is well known that we receive no Government funding for our annual summer Festival, and it is through the financial success of that event that we are able to support our annual tour, year-round education activity (both also supported by Arts Council England) and the filming of full-length productions. We have just completed a £6.5m investment in this amazing Production Hub - creating a state-of-the-art facility to bring together our expert making teams, so that we maintain our competitive edge in creating world-class opera.’

Stephen Langridge, most recently Artistic Director at Gothenburg Opera, spoke about his long history with Glyndebourne; he took his first steps on the lawn when his father, Philip Langridge, performed on-stage and early in his career directed two youth operas at Glyndebourne, Misper (1997) and Zoë (2000). Introducing the 2020 season, he said:

‘I am thrilled to be announcing this exciting season, a classic Glyndebourne Festival smörgåsbord offering comic, tragic, and magical opera from three centuries - but with a steely through-line of amazing women, powerful in politics, strong in their relationships, and brave in their faith.’

Glyndebourne Festival 2020

Dialogues des Carmélites is one of the most devastatingly powerful works in the repertoire. Set against the backdrop of the French Revolution, it is based on a true story of religious martyrdom and follows the struggles of a young woman faced with a harrowing decision, made all the more moving by a breathtaking score.

Glyndebourne’s new production will be directed by Australian director Barrie Kosky, returning to the company for the first time since his triumphant production of Handel’s Saul in 2015. Glyndebourne’s Music Director Robin Ticciati will conduct the London Philharmonic Orchestra and an exciting ensemble cast led by Australian-American soprano Danielle de Niese, making a role debut as the opera’s heroine Blanche de la Force.

Also making its first appearance at Glyndebourne next summer is Handel’s Alcina, in a new production overseen by two Italian artists, director Francesco Micheli and conductor Gianluca Capuano.

Over the past two decades, Glyndebourne has consistently surprised and delighted audiences with its fresh take on works by Handel, including acclaimed productions of Theodora, Rodelinda, Giulio Cesare, Rinaldo and Saul. The company is building on that record with the first major new UK production of Alcina for over 20 years. Set in a world of enchantment and magic, the opera calls for lavish stage effects, promising a visual spectacle for Glyndebourne audiences next summer.

Taking the title role is Russian soprano Kristina Mkhitaryan, with Armenian soprano Nina Minasyan as Morgana, Anglo-French mezzo-soprano Anna Stéphany as Ruggiero and American contralto Avery Amereau as Bradamante.

The third new production of the 2020 season is Beethoven’s emotionally-charged opera Fidelio, directed by the up-and-coming young British director Frederic Wake-Walker and conducted by Robin Ticciati. It will be the first new production of the opera at Glyndebourne in nearly twenty years and marks the 250th anniversary of the composer’s birth.

Fidelio is Beethoven’s only opera, giving audiences a rare opportunity to hear the composer’s work in the opera house, and features music as powerful and beautiful as any that he wrote for the symphony hall. An impressive cast includes British soprano Emma Bell as Leonore and British tenor David Butt Philip as Florestan.

The 2020 Festival sees the return of one of Glyndebourne’s greatest ever productions - John Cox’s definitive 1975 staging of Stravinsky’s sophisticated comedy The Rake’s Progress, designed by David Hockney. It will be the first chance to see the production at Glyndebourne in over a decade, with Czech composer Jakub Hrůša at the helm of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and a cast that includes American tenor Ben Bliss as Tom Rakewell, British bass Matthew Rose as Nick Shadow and British soprano Louise Alder as Anne Trulove.

Completing the season are revivals of David McVicar’s insightful production of Mozart’s landmark work Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Annabel Arden’s colourful production of Donizetti’s romantic comedy L’elisir d’amore.

Gus Christie said: ‘I’m delighted to be announcing Glyndebourne’s 2020 season today alongside our new leadership team. We have a really exciting line-up featuring two works that have never been staged here before - Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites and Handel’s Alcina. I’m also delighted that we’re presenting a new production of Beethoven’s Fidelio nearly twenty years on from the last. It’s always a treat to hear that great composer in the opera house.’

Following a successful launch in 2018, the Glyndebourne Opera Cup returns in 2020. The final will take place at Glyndebourne on 7 March 2020 and will once again be broadcast live by Sky Arts. Applications for the Glyndebourne Opera Cup open on 1 September 2019. Full details will be announced later this year.

The Glyndebourne Tour returns next autumn offering audiences across England a chance to enjoy world class opera on their doorstep. It features productions of Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and the return of the Behind The Curtain series with The Magic Flute: Behind the Curtain, taking audiences under the hood of Mozart’s final operatic masterpiece.

Glyndebourne Tour 2020 runs from 9 October - 5 December 2020. Following three weeks of performances at Glyndebourne, the Tour will visit Canterbury, Milton Keynes, Woking, Norwich and Liverpool. Further information and casting to follow.

Chair of Trustees of Glyndebourne Productions Ltd to Step Down

John Botts will step down as Chair of Trustees of Glyndebourne Productions Ltd at the end of this year’s Festival, but will remain on the Board. John will be succeeded as Chair by Hamish Forsyth, a Trustee since March 2013 and Chair of the Audit, Finance and Compliance Committee. Hamish, President of Capital Group Europe and Asia, brings a wealth of business, charity and opera experience. He is a Fellow of the Governing Body of Eton College, and a former Trustee of both the Royal Opera House and Grange Park Opera.

Gus Christie said: “My father asked John to join the Board in 1985 when he was working at Citibank and he has been a lynchpin for Glyndebourne ever since. He was instrumental in encouraging my father’s vision of rebuilding the new theatre and driving the fundraising strategy and membership structures which have kept us afloat throughout. He oversaw the transition from my father to me, and has constantly challenged and prodded us when we needed it, at the same time providing constant support and guidance. We are all hugely indebted to John for the leadership he has provided in keeping us financially independent, at the same time as maintaining our extremely high artistic and musical standards. I am delighted he is remaining on the Board and warmly welcome Hamish as his successor.”

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Glyndebourne.jpgPeter Sellars' kinaesthetic vision of Lasso's Lagrime di San Pietro

The dedication was a paean to the head of the Roman Catholic Church: “the most holy father, our lord Clement VIII, most excellent and great Pope. Most blessed father and most merciful lord”. But alongside such pragmatic and politic declarations lay more personal expression: “these tears of Saint Peter … have been clothed in harmony by me for my personal devotion in my burdensome old age’ (per mia particolare deuotione, in questa mia hormai graue età).

For his texts, Lasso chose 20 of the 42 octava rima stanzas which form the poem of the same title by Luigi Tansillo (1510-68). Tansillo’s poetry describes not the act of denial itself, as dramatized in Bach’s Passions, but rather the psychological after-effects of the agonised glance given by Christ to the apostle Peter, directly after the third denial, as recorded in the Gospel of Luke: ‘At that moment, while he was still speaking, the cock crowed. The Lord turned and looked at Peter. Then Peter remembered the word of the Lord, how he had said to him, “Before the cock crows today, you will deny me three times.” And he went out and wept bitterly.’

Peter then spends the rest of his life dwelling on his cowardice and error, living in the eternal moment of betrayal and longing for the release of death. In Tansillo’s poems, Peter contrasts his sin with the beatitude of the children massacred by Herod and goes to the site of Christ’s crucifixion where recognition of his undeniable and ineradicable cowardice overcomes him. He retreats to a cave and spends his remaining days repenting and, since self-forgiveness is impossible, yearning for divine grace.

The stanzas set by Lasso focus solely on the lacerating glance of Christ and its tormenting effect on Peter. Numbers 1 to 12 are concerned with the piercing power of Christ’s glance, with the act of betrayal recalled in the first four stanzas. The remaining 8 numbers tell of Peter’s self-rebuke; from number 15, the third-person voice is replaced by Peter’s own. There is no ‘narrative’ as such; rather the drama is internal, enacted with Peter’s soul.

In 1559, the Vatican placed Tansillo on the Forbidden Index: his Lagrime prompted an official pardon from Pope Clement VIII. It is tempting, and credible, to view Lasso’s Lagrime as an expression of the aging composer’s own individual penitence - and this is the reading adopted by Peter Sellars, the director of this kinaesthetic interpretation of Lasso’s composition, presented by the Los Angeles Master Chorale at the Barbican Hall. After all, the composer’s physical and mental state in his final years is documented in deed and letter: in the form of a pilgrimage to the Holy House of Loreto in 1585 and an appeal from his widow Regina to Duke Wilhelm of Bavaria attesting to her late husband’s ‘melancholia’ - on one occasion, he failed to recognise his wife, spoke often of his death and was afflicted by sleeplessness and ‘fandasey’ (fantasies).

Others, though, including scholar Alexander Fisher [1] , view Lagrime in broader contexts: as a meditative process that ‘served the ends of contrition for sin and, ultimately, penitance’, and thus representative of post-Tridentine ‘sacramental discourse’. Fisher notes that common to post-Tridentine Catholic meditation ‘is the devotee’s awareness of sin, lengthy mental examination of its nature and consequences, and implicit or explicit resolution to make amends, culminating in cathartic moments of dialogue with a divine figure.’: ‘What is clear is that the Lagrime resonates deeply with a specific brand of religious devotion that was assuming a dominant position in Counter-Reformation Bavaria.’ Fisher views the closing Latin motet, ‘Vide homo’, which follows the 20 madrigals as the conclusion of the ‘dialogue between individual sinner and saviour that was so central to these methods. For those skilled in music, the steady ascent through the modal system, culminating in the unexpected A durus [mode] as Christ responds to Peter in person, would probably have strengthened the impression of the Lagrime as a kind of spiritual journey leading inexorably from the consciousness of sin to that moment in which all sin was washed away’.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

I allow that I digress here from the immediate purpose of this review but feel the need to do so in the light of Sellars’ adamant declaration that, “At this point in his life [Lasso] does not need to prove anything to anyone. He is [composing Lagrime] because this is something he has to get off his chest to purify his own soul as he leaves the world. It’s a private, devotion act of writing, but these thoughts are now shared by a community - by people singing to and for each other”. Arguing that the chorus “carries the drama forwards”, Sellars suggests that the work accords with the ancient Greeks’ understanding of tragedy, “which I could also call an African understanding, where an individual crisis is also a crisis of the community”. We hear one man’s thoughts, but it is the community that absorbs them “and has to take responsibility: a collective takes on this weight of longing and hope”.

Okay. Perhaps I should not have read Sellars' 'explanations' in the programme article - an extensive, very informative historical, contextual, musicological and interpretative account by Thomas May - before the performance itself. The latter was much more persuasive.

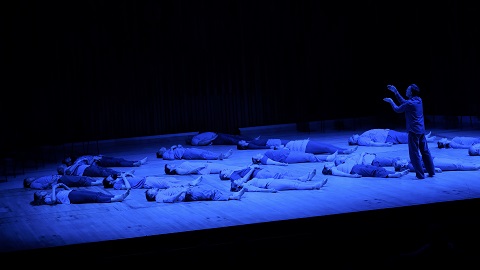

Three singers are assigned to each of Lasso’s seven vocal parts. The bare-foot singers are dressed in drab grey and mauve legging and slacks, shapeless tunics and ti-shirts. I was surprised to find Danielle Domingue Sumi credited as ‘costume designer’ - especially as conductor Grant Gershon (also barefoot, in black) explains that they strove for ‘clothes that look like they could come out of anyone’s wardrobe’: I thought they had. But, I guess the drab attire reflected the blanched landscape of Peter’s psychological wilderness. And, it allowed the singers to move naturally around and across the Barbican Hall stage.

For, this is what Sellars conceives as a physical and kinaesthetic representation of polyphony which is “totally sculptural”: the “muscular intensity in Lasso’s writing [that] is reminiscent of this expressive language we know so well, visually, from Michelangelo […] the muscle of spiritual energy and striving against pain to achieve self-transformation”.

So, ritualised movements, complemented by surtitles in colloquial vernacular, are designed to conjure the sculptural majesty of Renaissance art and architecture. And, how impressive the Los Angeles Master Chorale were in delivering harmonically and contrapuntally complex madrigals, their voices blending seamlessly and mesmerizingly, all the while adopting geometrical formations, pairings and poses; lying down, and sitting up; standing alone in alienated misery and clutching colleagues in warming consolation. Jim F Ingalls’ lighting followed the psychological modulations, now bleached white, now cool aquamarine, then fertile gold, or warming orange. Oh, yes; they had memorised the entire sequence - nearly 90 minutes of music.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

Would it have been preferable to have a single voice to a part? Perhaps I would have liked greater presence from the soprano voices? And more shading and variety of tempo? But Peter’s agonies were intensified by the smooth sweetness of the collective lyrical expression. And, the attention to the electric charge igniting the poetical text and detail was masterful, in the madrigalian manner, and physically impressive. At the close of the 15 th madrigal (‘Váttene, vita va’ - Life, get you gone), the chorus lay down, forming a crucifix: “Afraid to die, I denied life,” Peter admits. How could the LAMC sing with such unified ensemble and sure intonation from such a position?

The physicality of the performance was emphasised by sudden silences and shifts, mimicking Peter’s psychological ups and downs. Some were dramatic, others disruptive. I couldn’t help but recall the simplistic clichés of school drama lessons at times. “The deadliest arrows that pierced his heart were the eyes of the Lord, when they fixed on him …” prompted a collective collapse to the floor (and, the singers stayed in tune …). There was much handwringing, chest-clutching, colleague-embracing. When, for the final few madrigals the singers retreated to chairs placed left and right, I felt some relief.

Lagrime closes with a Latin motet, setting the 13th- century French poet Philippe de Grève’s representation of Jesus’s final words: a plea for mankind to behold the Lord’s suffering - ‘Vide homo, quae pro te patior’ (Behold, man, how I suffer for you). The Lagrime, thus, end not with consolation but with rebuke: we do not transcend despair. Fisher argues that ‘Christ’s rebuke … is consistent with a reading of Lasso's cycle as systematic meditation: the Lagrime, after all, concludes with the reflection on sin and does not proceed further into the illuminative and unitive.’

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican.

So, an accusing voice confronts not just Peter but mankind. But, Sellars interprets such words as spoken in love: the chorus rise from their chairs and embrace one another.

In cathedral naves, the human narrative of such works as Lagrime can be lost; as the polyphony swirls around the vaulted ceilings, words are lost in an embracing blend designed to render the individual receptive to the divine. Sellars focuses on the psychological rather than spiritual, setting the transience of human mortality against the almost unbearable eternal present of the consequences of our actions. And, his reading is not without power and pertinence.

Claire Seymour

Lasso: Lagrime di San Pietro (Tears of St Peter)

Los Angeles Master Chorale, Peter Sellars (director), Grant Gershon (conductor), Jim F Ingalls (lighting designer), Danielle Domingue Sumi (costume designer)

Barbican Hall, London; Thursday 23rd May 2019.

[1] In ‘“Per Mia Particolare Devotione”: Orlando Di Lasso’s Lagrime Di San Pietro and Catholic Spirituality in Counter-Reformation Munich’ Journal of the Royal Musical Association, vol.132, no.2, 2007: 167-220.

Photo credit: Tom Howard/Barbican

Garsington Opera Announces 2020 season and 2019 Paris Performance

Verdi’s Un giorno di regno is directed by Christopher Alden making his Garsington debut and Tobias Ringborg returns to conduct. Richard Burkhard performs Belfiore, Henry Waddington Barone di Kelbar. Mozart’s Mitridate, re di Ponto is conducted by Clemens Schuldt making his Garsington debut with Tim Albery returning to direct. Robert Murray performs the title role. Dvořák’s Rusalka features Natalya Romaniw in the title role with Douglas Boyd conducting and Michael Boyd directing. A revival of John Cox’s legendary production of Beethoven’s Fidelio with conductor Gérard Korsten making his Garsington debut, features Toby Spence as Florestan and completes the season. The Philharmonia Orchestra will play for the Verdi, Dvořák and Beethoven and the English Concert for the Mozart.

Opening nights

28 May Un giorno di regno Verdi - Tobias Ringborg, Christopher Alden

29 May Mitridate, re di Ponto Mozart - Clemens Schuldt, Tim Albery

14 June Rusalka Dvořák - Douglas Boyd, Michael Boyd

25 June Fidelio Beethoven - Gérard Korsten, John Cox

On 19 September 2019 this season’s production of Don Giovanni with principals and chorus from Garsington Opera will be given a semi-staged concert performance at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris with the Orchestre de chambre de Paris conducted by Douglas Boyd and directed by Deborah Cohen.

The 30th anniversary season opens on Wednesday 29 May with four new productions - Smetana’s The Bartered Bride, Mozart’sDon Giovanni, the first UK stage performance of Offenbach’s Fantasio and Britten’s The Turn of the Screw. The season culminates with concert performances of Monteverdi’s Vespers of 1610, celebrating the start of a partnership with The English Concert.

Visit www.garsingtonopera.org for the few remaining seats.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Garsington%20Logo.jpgMay 23, 2019

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Donnerstag aus Licht

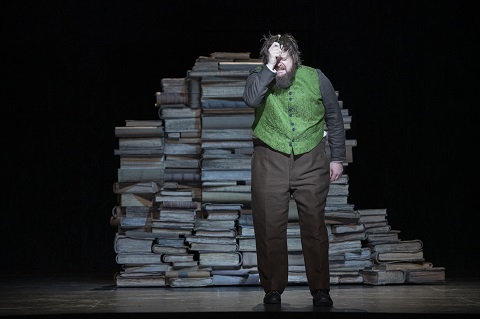

This exploration is particularly ripe in Donnerstag aus Licht - an opera attuned to Stockhausen’s reshaping of musical perceptions. Take away the impossibility of what the composer asks us to see and what are you left with? The answer is a mystical cosmos which probes the notion of invisibility in music, the relationship between space and time, of spatial divisions and oscillating perspectives in sound, the fusion of the electronic and the instrumental, and a matrix of ideas that is quite simply ravishing on the ears.

There is a clear argument for suggesting that what Stockhausen does in his Licht operas is to ritualise the concert experience - and this is probably a little more easy to identify in Donnerstag aus Licht, the opera which was written first and which often seems less extravagant than some of those which followed. Benjamin Lazar’s stage direction for this concert performance placed ritual at its epicentre; but his real achievement was to remain entirely - or, at least largely - faithful to the text without swamping it with detail. In what is often quite a personal and autobiographical work from the composer, this semi-staging often made this strikingly clear.

This is an opera which begins and ends outside the theatre, and in one sense this is entirely in keeping with its accumulating mass of thematic ideas, especially in the music Stockhausen composed for it. ‘Donnerstags-Gruss’ begins in the foyer, taking in music we will hear in the opera (those Bali riffs, for example). ‘Donnerstags-Abschied’ which ends it takes place outside the theatre - and proved acoustically rich on this occasion. With five trumpeters playing from high up on the balcony of the Royal Festival Hall, and in the front of the river, it was that very spatial dimension, the ebbing and flowing of perspective, which repeated so much of what you heard in the hall itself.

Act I (Michaels Jugend) is sparsely scored, but it throws us immediately into the triplicate format that Stockhausen rarely deviates from. Eve, Luzifer and Michael emerge - and then merge. ‘Kindheit’ is a trio devoted to childhood - of a mother teaching her son the days of the week, of Luzifer the rote learning of numbers. But it is about remembrance of the past, too. Of soldiers in Nazi Germany, of childhood hunting trips, of a mother’s descent into madness. This is the tragedy of any dysfunctional family - and Lazar’s direction doesn’t shirk from showing us this. In ‘Mondeva’ Eve is restrained by doctors, a needle injected into her neck (almost recalling the horror of forced Nazi euthanasia) and drowned in a bathtub; Luzifer dies on a battlefield. In ‘Examen’ Michael is seen auditioning for entry to a conservatory. Stockhausen didn’t necessarily have to look too far for the plot here because it largely came from his own past. But the complexity is in the shadows he creates - the trio of singers is replicated in a trio of instruments (a trumpet, a trombone and a basset horn) and by the end of the act they have all gone through the incarnations that come to symbolise the fracturing of time in Stockhausen’s world.

It was immediately apparent from the very beginning of Act I how superlative the singing was, how entirely immersed in the roles the soloists were. It was to be a hallmark of the opera throughout. Léa Trommenschlager’s Eve was extraordinarily powerful - but she managed to bridge motherly tenderness with simplicity; when she began her descent into madness you were reminded of Seneca’s Medea - but in almost pocket-sized form. Hubert Mayer’s Michael managed to achieve the impossible - a reduction of his voice into youthfulness and innocence, with just a hint of inquisitiveness. Damien Pass’s Luzifer is a voice centred on a dark, rich bass - but how stentorian he was, almost terrifying at times. One could argue amplification made all these voices more focussed and more forward than they might normally sound, but the upside was their German was impeccably clear.

Iris Zerdoud (Eve, basset horn). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton/Southbank Centre.

Iris Zerdoud (Eve, basset horn). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton/Southbank Centre.

Act II (Michaels Reise um die Erde) is unusual in that it is derived entirely from instrumental and electronic forces. Stockhausen thinks somewhat outside the box here in that Michael (this time as a trumpeter) travels the earth in a vast globe while the orchestra are penguins at the bottom of a glacier-covered world. Lazar’s compromise (for that is all he can do) is to have a projector screening the rotating of a celestial orb - almost with the randomness of a dice being thrown - with each stop on this whistle-stop journey being shown. We travel to Cologne (perhaps not that coincidental since it was where Stockhausen was born), New York, Japan, Bali, Central Africa and India. The stops might be brief - but the styles are ever-changing, like a musical kaleidoscope.

This is an act that is about conflict and combat; but it also one that is about a journey entwined in love and eroticism. It is a tour de force of musical creativity, enormous virtuosity and skill - often asking its central characters to play their instruments and act simultaneously as well. Benjamin Lazar’s direction left nothing to the imagination here and this was simply galvanising theatre. In its most basic form, this whole second act is like a vast trumpet concerto though the interplay between instruments really makes it more than this. It opens with Michael’s trumpet (the magnificent Henri Deléger) and Luzifer’s trombone (the equally superb Mathieu Adam) engaged in a duel, sparring centre stage with instruments flashing like foils. A clarinet (Alice Caubit) and basset horn (Ghislain Roffat) buzz around the orchestra, menacingly and waspishly, acting like clowns. Michael duets with a tuba (Stuart Beard) and then slays him like a bear. A love scene is played out between Michael and Eve (here played on the basset horn by Iris Zerdout) though it seems both macabre and heavily ritualised in its love-making with an almost sleazily erotic edginess to it.

The two scenes that comprise Act III (Michaels Heimkehr) are vastly different in scale. ‘Festival’ is for large choral forces and orchestra; ‘Vision’ is like chamber music, focussed mostly on the Michael performers and acts as a kind of summation of all that has gone before. For some, ‘Vision’ can draw one in with its cathartic, hypnotic translucence; for others, it’s a long-drawn out epilogue where the attention flags. Which camp you fall into will largely depend on the quality of the three Michaels - and also on the dramatization which accompanies them through the half-hour stretch this music takes. I think this performance succeeded - perhaps narrowly - in taking us into the cathartic side.

Damien Pass (Luzifer), Emmannuelle Grach (Michael). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton/Southbank Centre.

Damien Pass (Luzifer), Emmannuelle Grach (Michael). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton/Southbank Centre.

Act III didn’t really disappoint in its relative closeness to the text. This act is all about Donnerstag aus Licht in tri-form - Eve, Michael and Luzifer are all, at one stage or another, represented as singer, instrumentalist or dancer. Eve presents Michael with three plants, the branches of which he interprets as rays of light, and there follows three light shows. As the words “then streams come down” appeared on screen so the light show began - multi-coloured lasers, in broken shards, or diamond trellises, a web that stretched across the stage. A tam-tam glowed like a sun (or perhaps a moon), for it to shift into an eclipse. With the words “glass suns” it seemed to be refracted in a mirror, but then became the iris of an eye. Act III is the depiction of Michael returning to his celestial home - and Lazar took this more than literally.

Invisible choruses are heard on tape - but they are then taken up by five sectional choruses divided around the stage. But there is conflict as well. The Michael and Luzifer dancers tumble and fight, soon to be joined by the trumpet and trombone in battle - until Luzifer is vanquished. But he reappears in his human form as tormenter. ‘Vision’ is almost a kind of shadow play, the learning curve through which Michael has travelled on his journey.

There is an undeniable feeling of completeness in Donnerstag aus Licht as you experience it, not least because it seems self-contained as theatre. But, you can also begin to see the disintegration of the structure Stockhausen was to bring to later Licht operas in how the acts themselves are conceived. Benjamin Lazar’s concert staging perhaps isolated this more than one might have expected - the bareness of Act I seemed very hollow against the overwrought franticness of ‘Festival’ from Act III. Much of ‘Festival’ had been very impressive, even if it felt just a little too like a carnival at times - Mathieu Adams’s trombone-playing and tap-dancing Luzifer was simply extraordinary to watch, for example. Henri Deléger’s trumpet-playing Michael was so heroic, the timbre so assured whether the playing was muted or played open, that he was clearly the dominant force here. It’s rare that you hear such colour brought to this instrument, but here it was so variegated. Jamil Attar’s Luzifer (as dancer) was elliptical in his body-shaping, athletically brilliant but with every movement seemed to synchronise with the tenebrous shadows that Pass’s vocal Luzifer breathed like fire.

Henri Deléger (Michael, trumpet). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton/Southbank Centre.

Henri Deléger (Michael, trumpet). Photo credit: Tristram Kenton/Southbank Centre.

The three Michaels in ‘Vision’ were a mesmeric trio. One of the difficulties Stockhausen can sometimes over-emphasise in the Licht operas is an indistinct timbre in the vocal line. These are characters at different stages, and they imply different things through a long journey. Hubert Mayer’s younger Michael never wavered in his innocence. Safir Behloul was hugely impressive as the Act III Michael - especially in ‘Vision’ where so much of his singing shifts from German into a kind of Stimmung style of phrasing. Deléger’s often breathtaking trumpet playing just dazzled in its tone colours.

Le Balcon, the London Sinfonietta, the Royal Academy of Music Manson Ensemble and New London Chamber Choir - under the enormously assured and flexible baton of Maxime Pascal - couldn’t have given better support.

It’s rare you hear any opera where there are no weak links - but this performance of Donnerstag aus Licht was pretty faultless on multiple levels. So much of this had to do with the enormous clarity of the music we heard and not the obfuscation of a complex direction. What Benjamin Lazar advocated so strongly for is a design which had theatre, movement and lighting but allowed the conductor Maxime Pascal to illuminate the instrumental music, the tape sounds, the voices and soloists in a way which played to the strengths of Stockhausen’s sonorities. If the Royal Festival Hall can sometimes seem an opaque acoustic, here it was transformed into one which was rather revelatory. The ears were not just once or twice seduced by the mysterious effect of sound - it was a commonplace feature. This was an adventure, rather than simply a performance. Or, as a young man who happened to be passing through the terrace during the ‘Donnerstags-Abschied’ said to me: “It’s really trippy”. He really couldn’t have come up with a better description of what Stockhausen is all about and what this completely memorable evening so amply demonstrated.

Stockhausen: Cosmic Prophet continues on 1st - 2nd June 2019, Southbank Centre

Marc Bridle

Karlheinz Stockhausen: Donnerstag aus Licht

Léa Trommenschlager (soprano, Eve Act 1), Elise Chauvin (soprano, Eve Act 3), Hubert Mayer (tenor, Michael Act 1), Safir Behloul (tenor, Michael Act 3), Damien Pass (bass, Lucifer), Dancers (Emmanuelle Grach - Michael, Suzanne Meyer - Eve, Jamil Attar - Lucifer; Maxime Pascal (conductor), Christophe Naillet (lighting design), Florent Derex (sound projection), Augustin Muller (computer music design), Yann Chapotel (video design, Alice Caubit (clarinet, clownesque swallow Act 2), Ghislain Roffat (clarinet/basset horn, clownesque swallow Act 2), Iris Zerdoud Eve (basset horn), Henri Deléger (trumpet, Michael), Mathieu Adam (trombone, Lucifer), Alphonse Cémin (Michael's accompanist) Simon Guidicelli (double bass, Doctor Act 1), Le Balcon, London Sinfonietta, Royal Academy of Music Manson Ensemble, New London Chamber Choir.

Royal Festival Hall, London: 21st May 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Donnerstag%20aus%20Licht-RFH-817%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Stockhausen: Donnerstag aus Licht, Royal Festival Hall product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=Above: Léa Trommenschlager (Eve)Photo credit: Tristram Kenton/Southbank Centre

May 22, 2019

David McVicar's Andrea Chénier returns to Covent Garden

There are indeed some elements of historical realism. On 17th July 1794, the poet André Chenier was taken by tumbrel from his cell in the Prison Saint-Lazare in the 10th arrondissement, in which he had been incarcerated since 7th March, to what is now the Place de la Nation (known as the Place du Trône-Renversé during the Revolution). Earlier that July day, he had been convicted of being an ennemi du people. He was one of the last people to be executed by Maximilien Robespierre, who was himself guillotined just three days later, during a period of chaotic violence which saw, in one 46-day period alone, nearly 1300 succumb to the guillotine’s slicing finality.

But, the verismo operatic ‘school’ does not equate with realism. Yes, Andrea Chénier gives us some anthems and songs - the ‘La Marseillaise’ and ‘Ça ira’ among them. And, Luigi Illica’s libretto, inspired by the life of the French poet André Chénier (1762-94) does draw upon historical and fictional documents such as the 1819 notebooks of Henri de Latouche, Chénier’s first editor; Jules Barbier’s 1849 drama about the eponymous poet-philosopher’s tragedy; and the Goncourt brothers’ History of French Society during the Revolution of 1854. Some of the numbers, such as the eponymous protagonist’s ‘Un di all’azzurro spazio’, which fuses revolutionary anger with poetical euphoria are derived from Chénier’s works (in that particular case, the 1787 Hymn to Justice). And, Giordano’s opera was a success in its day, perhaps because the battle-cries of the risorgimenti were still ringing in the air, and many a European monarch of the day was a victim of, or anxious about, an assassination attempt.

But the political context, which is so present in Massenet’s Thérèse or Poulenc’s Dialogue des Carmelites is blanched from Giordano’s ‘revolutionary’ opera. This is no surprise: the ‘verismists’ customarily modified history, particularly as their focus shifted from low-life suffering to exotic glamour.

So, it is neither surprising nor inapt that David McVicar’s ROH production for the ROH, revived here for the first time, is more a BBC Sunday-night television period-piece than republican bloodbath, for all the splashes of verisimilitude - one drop-cloth proclaims Robespierre’s damnation of Chénier: ‘Even Plato banned poets from his Republic’.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Though many have denigrated its shortcomings, Giordano’s opera has its merits, not least an economical and swift libretto by Illica, that conjures a dramatic sweep across varied locale and confines its protagonists to ever more oppressive and limiting domains: from ancien régime pleasures to the austere deprivations of prison; from public tribunal to the scaffold.

Revived for the first time, McVicar’s 2015 production tells its tale straight and plumps for designer-realism: even the san culottes look designer-attired. Low-hanging chandeliers glisten; gavottes are danced with an ironic lack of class-crossing awareness. Perhaps there are some political points being made here, but if so they make a weak impression. Robert Jones’s sets impress with their sumptuousness and adaptability, not for their subversion.

Dimitri Platanias as Carlo Gérard. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Dimitri Platanias as Carlo Gérard. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

In 2015 , Jonas Kaufmann picked up the quill and defied the interrogation of Robespierre’s terrorists. On this occasion it was the turn of Roberto Alagna, marking his 100th performance at Covent Garden. Despite the present-day dearth of tenors equipped for the challenge, the three arias for Chénier -among the finest written for a ringing Italian tenor - have contributed to the opera’s ‘survival’ in the ‘canon’. And Alagna certainly has the necessary heft and volume. If that was all he delivered, then who are we to complain. The role lies low, yet Alagna had no problem finding the required declamatory pressure and projection in his baritonal range, and the high notes were true, sustained and sure. This Chénier may have been missing a bit of musical ‘poetry’ but there’s a lot to be said for security - even if it isn’t particularly ‘revolutionary’. Alagna’s self-defence at the Terror tribunal, ‘Sì fui soldato’, was a compellingly proud confrontation with death.

Dimitri Platanias communicated all of the footman (and rival of Chénier) Carlo Gérard’s complexity and inner struggles with conflicting loyalties and motives. His manner was a little rugged, but that’s probably true to the role. Platanias had the rawness of an Iago in the more declamatory episodes, while in ‘Nemico della patria’ the baritone wrung every drop from every note.

As Maddalena di Coigny, American soprano Sondra Radvanovsky exhibited a bit of a ‘wobble’ at the climactic highpoints but was wonderfully expressive when singing quietly - which she was not, fortunately, disinclined to do. Her narration of her mother’s tragic death, ‘La mamma morta’, was beautifully executed: compelling, replete with pathos and sincerity. Her duets with Alagna, particularly that at the close of Act 2, were gripping - there was some chemistry here - and dramatically and musically uplifting, as they should be.

Rosalind Plowright as Countess di Coigny. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Rosalind Plowright as Countess di Coigny. Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The choral scenes had great energy, and lyrical fervour; and those in the minor roles - Rosalind Plowright as Countess di Coigney (on the eve of her 70th birthday!), Christine Rice as Bersi, Stephen Gadd (as Pietro Fléville) and Aled Hall (as The Abbé) made a strong impression. Conductor Daniel Oren didn’t tap the suavity of the score - the overall effect was as rough and ready as Gérard’s complaints - but he kept things moving along.

In comparison with the political (and social) meltdown that is imminent as our the lower House attempts to negotiate its own ‘revolutionary’ path, this production may seem more reactionary than revolutionary; but, Alagna et al deliver the goods and there’s a sumptuous sheen that glosses historical grimness and gore.

Claire Seymour

Andrea Chénier - Roberto Alagna, Maddalena di Coigny - Sondra Radvanovsky, Carlo Gérard - Dimitri Platanias, Bersi - Christine Rice, Countess di Coigny - Rosalind Plowright, Major-Domo - John Cunningham, Pietro Fléville - Stephen Gadd, Abbé - Aled Hall, Mathieu - Adrian Clarke, The Incredibile - Carlo Bosi, Roucher - David Stout, Madelon - Elena Zilio, Dumas - Germán E. Alcántara, Schmidt - Jeremy White; Director - David McVicar, Conductor - Daniel Oren, Set designer - Robert Jones, Costume designer - Jenny Tiramani, Lighting designer - Adam Silverman, Movement director - Andrew George, Revival Director - Marie Lambert, Revival Choreographer - Colm Seery, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 20th May 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/%3DRoberto%20Alagna%20as%20Andrea%20Ch%C3%A9nier%2C%20Sondra%20Radvanvsky%20as%20Maddalena%20di%20Coigny%20%28C%29%20ROH%202019.%20Photograph%20by%20Catherine%20Ashmore.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Andrea Chénier: Royal Opera House, Covent Garden product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Robert Alagna (Andrea Chénier) and Sondra Radvanovsky (Maddalena di Coigny)Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore

May 21, 2019

Glyndebourne presents Richard Jones's new staging of La damnation de Faust

The work is a notoriously fragmentary hybrid, as quixotic as its eponymous ‘protagonist’, in which the unstable relationship between the ‘real’ and the ‘imagined’, between the ‘tangible’ and the ‘idealised’, is both the ‘perfect’ embodiment of Berlioz’s ‘meaning’ and irreconcilably opposed to coherent theatrical presentation.

That doesn’t stop people trying. And, any director who tries has fathom how to deal with the work’s innumerable gaps, inconsistencies, multiplicities and conflicts - in the music and in the drama, of style and of mode.

In the music there are symphonic narratives; oratorio-like choruses which comment on events in the past; set-piece marches, dances and songs, some diegtic; operatic recitative and quasi-aria. Sometimes the music takes us into a character’s consciousness and invites us to experience their feelings, as in Faust’s invocations in which the music presents his response to his immediate world, thus communicating his inner life. At other times, such musical empathy is denied us, such as at the start of the work when Faust tells us he can here choruses: ‘All hearts throb to their victory song.’ We do not hear such songs, and we remain alienated from his experience. Then, the music sometimes roots the action in reality: we hear students singing in the streets, military tattoos and fanfares.

The drama lacks tension. Characters sometimes address each other but they do not ‘converse’. Are their relationships real or allegorical? There are flesh-and-blood soldiers and students alongside flying demons and hallucinatory visions. Situations are often unspecified and discontinuous. For example, waiting in vain for Faust’s arrival, Marguerite sings the romance ‘D’amour l’ardente flame’: she could be anywhere, and the moment could be placed either before or after what we have just seen and heard. The action resumes subsequently, with Faust in the countryside. There is no clear chronology or causal relationship.

Ultimately there is no unity; and this is Berlioz’s intent. The real and the imagined meet on the stage and in the score. So, if one stages the work, what should the theatrical stage ‘represent’? An identifiable time and place? Or, a magical ‘anywhere’? Specificity destroys illusion; dream-like passages destabilise reality. Clearly a different, new kind of logic must prevail.

In this new staging at Glyndebourne, Richard Jones gives us his own brand of ‘logic’ but ‘coherence’ eludes him. Before we hear a note of music, dancing demons in lurid body suits and horned masks limber up, as if for a sporting contest; then, a chorus of fiends takes its place in the stalls perched on three sides above the black box set through the cracks of which lurid lights glow. These are, apparently, the students who will observe Méphistophélès’ masterclass in malevolence - though they might as well be spectators at a gladiatorial combat. Or an audience at the theatre, an effect enhanced when Méphistophélès turns to address us: “my devils”. Aloft, they resemble the chorus in an oratorio, commenting on the action; when they descend, they become participants in the drama, effecting ‘now-you-see-me now-you-don’t’ changes of costume which further makes the audience complicit in the deception of Faust.

Marguerite (Julie Boulianne), Méphistophélès (Christopher Purves) and Faust (Allan Clayton). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Marguerite (Julie Boulianne), Méphistophélès (Christopher Purves) and Faust (Allan Clayton). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

So far so good: the work’s hybridity is reflected in this conceit. And, if the work is to succeed on the stage it should surely do so on its own terms. But, immediately Jones starts meddling. The entry of a Méphistophélès - a Paganini-like figure, swathed in a black, embroidered trench coast, with lanky red hair and clutching a battered violin case - marks the first of Jones’s ‘amendments’: he has added spoken text, written by Agathe Mélinand and based upon Goethe but with, in Jones’s words, “what’s germane to Berlioz”. Presumably such text is designed to ‘fill in’ the gaps in the narrative but it simply unbalances the ‘theatre v. oratorio’ relationship still further - and it didn’t help that Christopher Purves’ weary opening lines had a few unintended hiatuses.