June 30, 2019

The Cunning Little Vixen at the Barbican Hall

And history is on their side. An advertorial in the Brno newspaperMoravské noviny, prior to the premiere of the opera at the Na hradbách Theatre on 6th November 1924 had little to say about the music or the design, but promised the paying public ‘seventy costumes’ designed by artist Eduard Milén, including - as Jennifer Sheppard notes in her article ‘How the Vixen Lost Its Mores: Gesture and Music in Janáček’s Animal Opera’ - ‘grasshoppers and crickets in “yellow-green tailcoats and magnificent little wings”; black-and-white glow-worms with reflectors “to light up their bottoms” in the night scenes; a wire-frame rooster costume lined with brightly coloured fabrics; and a green, blue and black dragonfly of “melancholy beauty”, whose tiny, delicate underwings were illuminated in glittering gold’. [1]

Not to be outdone, for their first production of the opera in May 1925 the Prague National Theatre engaged Josef Čapek, brother of the author Karel, as designer, and he duly dished up ‘flying goggles for the mosquito; flouncy polka-dot petticoats for the hens; cowboy spurs with golden rowels for the rooster; a furry deerstalker for the forester’s dog’ (Ibid).

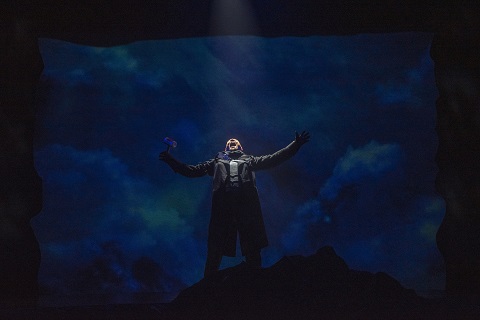

Such aspirations for mimicry-cum-verisimilitude are not on the agenda of Peter Sellars, whose production of Vixen - first seen in Berlin in 2017 - was performed at the Barbican this week by his long-term collaborator and friend, Sir Simon Rattle, and the LSO. Here, minimalism prevails. The entire cast - soloists, London Symphony Chorus, the children of LSO Discovery Voices - are dressed in simple black and perform the action on a bare raised platform in from of the orchestra. Props comprise the odd chair or table, carried on by cast members as required.

Sophia Burgos (Fox) and Lucy Crowe (Vixen). Photo credit: Mark Allan.

Sophia Burgos (Fox) and Lucy Crowe (Vixen). Photo credit: Mark Allan.

In the light of Janáček’s rather arbitrary ‘pairings’ of man and beast - the same singer takes the roles of the Forester’s wife and the Owl, the Priest’s animal embodiment is the Badger, and the inebriate Schoolteacher and Mosquito share a role and a bottle - my first thought was how on earth were we to distinguish the animals’ identities and their human correlations? But, I need not have worried: video designers Nick Hillel and Adam Smith (of Yeast Culture) offer an Attenborough-esque Planet Earth natural history side-show which presents tadpoles as they wriggle into life, dragonflies engaging in shimmering. flickering mating rituals, peering owls, migrating geese, fluttering sun-flecked forests and moonlit mountains.

Indeed, Sellars’ approach pre-empts objections which are sometimes voiced about the stylisation of gesture in which some productions indulge; and if we can’t always differentiate between man and animal, then this only serves to emphasise the inter-connectedness of the entire natural world, man included.

Billboards in Brno in 1924 had enticed prospective punters, ‘It will be a dream, a fairy tale that will warm your heart’, but there is no sentimentality in Sellars’ Vixen. That’s not to say that it does not touch one’s heart, but the strings it pulls of the more sombre, dark kind. Warmth came in the form of the wonderful playing of the LSO. The score includes many instrumental episodes, which are often both balletic and mimetic, and Sir Simon Rattle ensured that every rhythm was delineated with pulsating vigour, every surge of harmonic passion blossomed fulsomely, every extreme of register was meticulously scaled: there was some especially beautiful playing from the strings. In the programme booklet Rattle declares this opera was “the piece that made me want to become an opera conductor … and [its] still one of the pieces that reduces me to tears more easily than any other”, and the loving tenderness with which he articulated the score’s emotions and dramas might well have inspired a tear from many in the Barbican Hall. The LSO did not just mimic or suggest stage movement or feeling, they took responsibility for the drama, filling in the gaps in the episodic structure, immersing us in a glorious musical embrace.

Photo credit: Mark Allan.

Photo credit: Mark Allan.

Lucy Crowe was a stunning Vixen - insouciant, courageous, feral, sensuous, daring, brazen and honest. This is one of best things I’ve seen Crowe tackle. This Vixen was strong and nimble, and Crowe relished the physical animation as much as she did the vocal vivaciousness. Standing astride the Forester’s kitchen table she impassionedly goaded the repressed hens into socialist revolt, and when she failed, she resorted to tricksy tactics, claiming that she’d rather be buried alive than live with such losers. A winning move: the Cock’s vanity got the better of him and his ‘bravery’ saw him succumb to the ‘playing dead’ mime. The Vixen’s gluttonous gourmandising on chicken skewers was played out in gloriously chin-greasy detail on screen.

Crowe’s Vixen was both ethereal - her soprano silky in the reflective soliloquies - and earthy. In the cartoons by Tĕsnohlídek upon which the opera was based, the Vixen relieves herself into the badger’s den to force him to evacuate, and Crowe sprayed with gleeful vigour! She sang with flashes of brightness and fire, balanced by soft sensuousness. It was an utterly beguiling performance.

Sophia Burgos’ Fox was surprisingly tender: no strutting and posing here, instead coaxing and caring in a beautiful love duet with the Vixen. Initially I thought that Burgos struggled to carry over the strong orchestral fabric, but she grew in stature, crafting a convincing personality: a sort of house-husband of paternal benevolence, anxiously ushering their growing brood of cubs into the under-stage den when their mother was threatened by Hanno Müller-Brachmann’s Poacher, Harašta, after she’d raided his basket of poultry. If the Vixen’s death did not seem quite so shocking as it sometimes can do, then that did not seem to matter: the Vixen’s death was not the climax of a dramatic arc but rather just one happening, incidental and quickly forgotten by a natural world whose chief concern was to nurture the next generation.

As the Forester, Gerald Finley’s performance captured the moral complexities faced by the humans living in the forest. Amorality met anxiety met ambiguity in the personage of this Forester. This was an expressive tour de force. And, a vocal triumph too. Some may have objected, but I loved the way that the original cartoon’s intimations that the Vixen was the animal embodiment of Harašta’s seductive beloved, Terynka, was referenced in Finley’s encounter early with the Vixen - a passionate love-making accompanied by overflowing orchestral warmth, which teased out myriad emotions. Upon returning home, the Forester was met with a disapproving scowl from his Wife, richly sung by Paulina Malefane (also Owl and Woodpecker). Was the encounter real or imagined? The ghostly green glow in which the encounter was bathed by lighting designer Ben Zamora made it difficult to know. But, their subsequent struggle in which they seemed locked was as much a physical one as a psychological one: with the Vixen, by turns, beaten for stealing the Forester’s food, biting back in defiance, nestling needily alongside her captor, needling him with her desire for freedom.

Photo credit: Mark Allan.

Photo credit: Mark Allan.

This was a luxuriously cast performance, even allowing for the dearth of native Czech speakers. Peter Hoare was equally commanding and characterful as Schoolmaster, Cock or Mosquito; Jan Martiník was a fine Parson/Badger, gruff and glum. Müller-Brachmann stalked opportunistically and menacingly around the Barbican Hall, his hunting gun perched, ever-ready. Anna Lapkovskaja’s Dog was convincing put out by the arrival of a usurper in the Forester’s household, but animal instinct took over though the companionship she craved was denied her. The London Symphony Chorus sang with vigour and managed their entrances and exits swiftly, while the children of the LSO Discovery Chorus were well drilled, vocally and dramatically, charming us in every scene in which they appeared.

And, what of Sellars’ slide-show? Well, images such as the gruesome hunter’s trap and the conveyor belts of chickens heading to their destined doom certainly made their mark. But, the city apartment blocks were an odd evocation of the Forester’s milieu and the folk dancers who supplied the entertainment at Harašta’s wedding seemed less fitting. Overall, I found the visuals rather hyperactive: however well one knows the opera, how could one take in the dramas playing out on both screen and stage, in song and symphonic strata, simultaneously?

The three Acts ran segue with no interval; in fact, Rattle allowed barely a breath between Acts - just enough time to get personnel off-stage and back on again. The effect was to cohere the episodic scenes - which have little to connect them, chronologically or in terms of dramatic linearity - into one flowing stream of nature, emphasising not so much the epiphanic rebirth that the Vixen’s death bestows upon the Forester, but rather the continuous renewal of life, and the speed of transitions between seasons and generations. At the close the Forester espies the Frog: not you again, he declares, only to be answered by a cheeky, slimy nose-rub and the riposte, “That wasn’t me, it was my grandfather. He told me all about you.” The moment was simultaneously insouciant and of import: here was the brevity of life, the brutality and benevolence of nature. Like the whole performance, it was beguiling and brilliant.

Claire Seymour

Gerald Finley (Forester), Lucy Crowe (Vixen), Sophia Burgos (Fox), Jan Martiník (Badger/Parson), Peter Hoare (Mosquito/Cock/Schoolmaster), Hanno Müller-Brachmann (Harašta), Irene Hoogveld (Jay), Anna Lapkovskaja (Mrs Pašek, Dog), Paulina Malefane, (Forester’s Wife/Owl/Woodpecker), Jonah Halton (Pásek); Peter Sellars (Director), Sir Simon Rattle (Conductor), Ben Zamora (Lighting Designer), Nick Hillel and Adam Smith (Video Design/ Yeast Culture), London Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Chorus, LSO Discovery Voices.

Barbican Hall, London; Thursday 27th June 2019.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/Forrester%20and%20Vixen.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Cunning Little Vixen: Sir Simon Rattle, LSO, Barbican Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Lucy Crowe (Vixen) and Gerald Finley (Forester)Photo credit: Mark Allan

Barbe-Bleue in Lyon

Unlike Mr. Pelly’s straight forward, very charming Peruvian fantasy, La Perichole that I saw at the Marseille Opera in 2002, or his parody of The Barber of Seville (sung on top of sheets of musical score paper) seen at the Marseille Opera in 2018 (boasting the hyper personalities of Stephanie d’Oustrac as Rosina and Florian Sempey as Figaro), here Mr. Pelly’s Barbe-Bleue is set on a farm near Paris and in a grand salon in the Élysée Palace, with actors of limited personality.

The real Barbe-Bleue is the 1619 folk fairy tale by Charles Perrault which Offenbach parodies à la Second Empire. But Mr. Pelly’s stretches the parody to include a parody of his own — that of opera stagings which imitate the criminal underworld (Bluebeard is dressed and acts like a mobster) and a parody of mindless operettas (King Bobeche is a pompous fairy tale king with a silly fairy tale court).

The Farm

The Farm

The time is now or maybe not-so-long-ago. We see a backdrop that is a latest edition newspaper, two front page articles discuss the strange murders. There is a tractor and chicken sounds and some bales of straw to convince us that all this is somehow what real is. Then we see a huge shelf of weekly revues (magazines), those that thrive on news of lurid allure, maybe true and maybe not. It is a side wall of the grand salon in which such tales of the rich and powerful evidently take place.

All this operetta scenery did not add up to a convincing stage for Offenbach’s amusing serial murders, particularly when we saw the refrigerated lockers of a morgue where Bluebeard’s victims are stored. We do know that "bluebearding" women (serial murder of women) is a real, recognized syndrome, but Mr. Pelly and his long-time designer Chantal Thomas only confused us about what may be real and what may not be.

From copious accounts we know that Offenbach’s muse during his very productive years at the Théâtre des Variétés was mezzo-soprano Hortense Schneider. We read of the very great charm of her performances but, alas, we have no digital records of them. Plus what was charming in the Parisian 1860’s may not charm us these days.

It is however the charm, whatever it may be, of an Offenbach heroine that wins our attention and ushers us into his music. The Lyon Boulotte (the Hortense Schneider role) was bravely undertaken by Héloise Mas who can indeed boast Boulotte’s “Rubenesque” body. Mlle. Mas was directed to be a bratty, tomboy rustic — maybe Mr. Pelly’s idea of real — forgetting that first of all Offenbach’s Boulotte must be a comic diva.

The Palace

The Palace

Bluebeard himself, played by tenor Yann Beuron, was directed to be oily, dangerous and thoroughly unsavory. Though not the usual mild-mannered, reclusive murderer we read about in actual newspaper accounts of such murders, perhaps Mr. Beuron’s Bluebeard fulfilled Mr. Pelly’s idea of a real murderer.

If the two protagonists of the Lyon Barbe-Bleue were meant to be real, the balance of the cast was rendered quite irreale. Prince Saphir played by Carl Ghazarossian and Popolani played by Christophe Gay were physically willowy, and both had an annoying lock of hair that fell across their faces. Count Oscar was willowy as well. The three men exuded a similar maximal energy in executing their roles while avoiding any distinguishing personality or character.

Fleurette, played by soprano Jennifer Courcier, King Bobeche played by Christophe Mortagne and Queen Clementine, played by Aline Martin were stock operetta characters. The thirty-six choristers were directed as if they were collectively one character — they made unison, abstractly choreographed movements.

Maybe a less slick reading of the score by conductor Michele Spotti and a less slick performance by the Opera de Lyon orchestra might have allowed a bit of Barbe-Bleue’s innate charm to slip through.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Barbe-Bleue: Yann Beuron; Le Prince Saphir: Carl Ghazarossian; Fleurette: Jennifer Courcier; Boulotte: Héloïse Mas; Popolani: Christophe Gay; Le roi Bobeche: Christophe Mortagne; Le Comte Oscar: Thibault de Damas; La reine Clémentine: Aline Martin. Orchestre et Chœurs de l'Opéra de Lyon. Conductor: Michele Spotti; Mise en scène et costumes: Laurent Pelly; Adaptation des dialogues: Agathe Mélinand; Décors: Chantal Thomas; Lumières: Joël Adam. Opéra Nouvel, Lyon, France, June 22, 2019

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Barbe-Bleue_Lyon1A.png

product=yes

product_title=Barbe-Bleue at the Opéra de Lyon

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Christophe Gay as Popolani, Héloïse Mas as Boulotte [All photos copyright Stofleth, courtesy of the Opéra de Lyon]

June 29, 2019

Mieczysław Weinberg: Symphony no. 21 (“Kaddish”)

This recording of Weinberg’s masterpiece, conducted by Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Gidon Kremer and the Kremerata Baltica, comes from the acclaimed live performance, part of the in-depth CBSO Weinberg series in November 2018. Though the symphony does get performed and has been recorded once before, this performance is exceptionally idiomatic as it is made by the finest specialists in the field, Gidon Kremer and Kremerata Baltica, supported by Gražinytė-Tyla and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, in top form. With these impeccable forces, it is unlikely that this performance will be surpassed for some time. This belongs in every collection, Weinberg-focused or not.

The combination of chamber orchestra, soloists and large orchestra is fundamental to structure and meaning. Embedding the ensemble and soloists within the orchestra shapes highlights individual voices against a wider background. In the apocalyptic tumult of the Holocaust, personal utterances must not be overlooked. This also extends the forces Weinberg can bring to bear in this panoramic landscape. “It is hard to string this bow”, said Gražinytė-Tyla of the interaction between ensemble and orchestra. “The reason is that long passages are dominated entirely by a solo voice and various chamber ensembles while the gigantic orchestral apparatus of almost 100 musicians sits on the stage” resurfacing at different points.

The Largo opens with the plaintive sound of Kremer’s violin, singing, poignantly, alone. Weinberg could be referencing many sources – the role of violinists in Eastern European culture, community fiddlers as well as trained virtuosi. On an autograph manuscript, Weinberg quoted the title of Mahler’s song Das irdische leben where a child cries out for bread, but is ignored, and dies. There are also quotes from Chopin’s Ballade no. 1 in G minor (Op. 23), further anchoring the Polish context in which Weinberg grew up. With muffled timpani, darker forces enter. There are moments when Kremer deliberately hardens the tone. But the violin soars upward, supported by the strings in the orchestra, before being silenced by a single, harsh drumstroke. The violin resumes reaching a very high tessitura above the steady pulse in the orchestra, before quietly subsiding as the orchestra shapes transparent, ethereal textures. The Allegro molto shatters any illusion of peace. This is graphic music. Ferocious chords and turbulent crosscurrents, interrupted by “gunfire” (percussion) and sudden, sharp outbursts of violence. The Largo is built around a chorale-like anthem. Tense, quiet passages alternate with more expansive motifs. Kremer’s violin re-emerges, bold, klezmer-like figures taunting strident, low-voiced brass. The Presto is manic, screaming alarums and madcap grotesquerie. Yet Kremer’s violin will not be stilled, its melody restrained but uncowed. As it fades, the Andantino rises, single notes plucked on violin, answered by the orchestra. This section is exquisite, executed with great poise, a reminder of civilized values.

In the Lento, the panoramic landscape of the Largo is redrawn. The violin is plucked, quietly, against a wash of high-pitched winds – winds suggesting movement and n the Lento, the panoramic landscape of the Largo is redrawn. The violin is plucked, quietly, against a wash of high-pitched winds – winds suggesting movement and change – bells ringing against ostinato discord, and a soprano voice is heard, singing a wordless plaint. The soprano is Gražinytė-Tyla herself, who trained as a singer and came from a music background. She knows how to carry a line, and the purity of her tone fits perfectly with what the voice might signify. The part is substantial and quotes passages that Kremer and the other soloists had played before. At moments her voice deepens richly before soaring upwards before the piano (Georgijs Osokins), clarinet (Oliver Janes), violin (Kremer) and double bass (Iurii Gavryliuk) return, the ensemble raised from the dead, so to speak, reunited with Gražinytė-Tyla’s song, growing with even greater affirmation than before. The symphony ends with a mysterious glow in this extraordinarily sensitive performance. This is a symphony of such multi-layered depth and subtlety that it rewards attentive listening.

Weinberg’s Symphony no. 2 (Op. 30) may have been written closer to the time the events described in Symphony no. 21, but traumas like that need time to process. In any case, Weinberg had to contend with Stalin and the Soviet authorities. Written for string orchestra, the textures are lighter, Gražinytė-Tyla conducting the Kremerata Baltica so the lines flow gracefully. The part for solo violin dominates, leading the ensemble forth. In the Adagio the violin takes flight. The higher strings follow but are met by a hushed section for lower strings. The Allegretto is lively: brightly poised and nicely defined.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Weinberg_Kaddish.png image_description=Deutsche Grammophon 483 6566 product=yes product_title=Mieczysław Weinberg: Symphony no. 21 (“Kaddish”); Symphony no. 2 product_by=Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, The City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Gidon Kremer and the Kremerata Baltica product_id=Deutsche Grammophon 483 6566 [2CDs] price=$15.99 product_url=https://amzn.to/2FGIegRThe Princeton Festival Presents Nixon in China

When it premiered at the Houston Grand Opera in 1987, just a decade and a half after the epochal events it portrays, Nixon in China received accolades. Since then, it has secured a modest spot in opera world, with two or three productions a year worldwide – but this understates its musical significance. Over the past three decades, other composers have adopted many of Adams’ innovative techniques, such as basing plots on current events, using romantic harmonies and melodies, quoting popular music, including surrealistic political satire, and amplifying singers.

Poet Alice Goodman did not write the libretto around a conventional plot. Instead, she recounts the ceremonial highlights of President Nixon’s famous visit – his arrival at Beijing Airport, meetings with the Chinese leaders, Pat Nixon’s experiences among the people, a state banquet, and a revolutionary ballet – as a basis for a surreal reflection on the tension between public duty and private life.

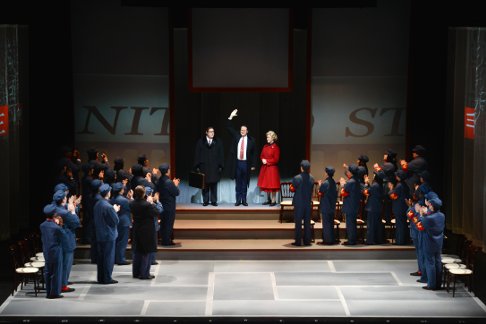

The Nixons and ensemble

The Nixons and ensemble

The libretto’s strength lies in a series of introspective monologues in which each character recounts important memories that shape their attitude toward politics. Goodman’s underlying point seems to be that most politicians are childishly self-important. So Madame Mao is a revolutionary fanatic who treats the creation of a perfect society as an aesthetic project. Kissinger is a doddering old fool who responds to Chou En-Lai’s desire for dialogue by asking to go to the toilet. President Nixon is an American provincial who obsesses on World War II. Mao is a cryptic old man muttering platitudes about his boyhood revolutionary achievements. All have lost touch with everyday virtues of family, community and humanity.

The remaining two characters offer a more sympathetic and humanistic alternative. Chou En-Lai’s elegance and sense of the historical moment fuel two memorable arias, one each at the end of the first and third acts. Pat Nixon expresses stereotypical virtues of “home and hearth” through her simple love of children, animals, community and other simple things.

Adams sets this libretto with a distinctive style of orchestral writing. Drawing on the minimalist tradition of Philip Glass and others, the score of Nixon in China rests on hypnotically oscillating block chords and arpeggios punctuated by syncopated notes. The challenge for minimalist music is that it lacks a clear architectural principle that allows music to develop harmonically and melodically over longer timespans. Climaxes are achieved almost entirely by increasing volume or speed. Minimalist music shimmers and even changes, but it does not evolve – in contrast to the music of Schubert, Wagner, Bruckner and other traditional composers who sometimes employed repetitive forms.

Ballet sequence

Ballet sequence

For Adams, the overall result is atmospheric but static music, more akin to a film score than a classic opera. In most scenes of Nixon in China, that mood is one of slightly mysterious introspection, as if one is seeking to remember something distant and ineffable – a suitable style for moments when characters reminisce. The result can be quite beautiful, as in Pat Nixon’s scena “This is Prophetic,” with its hypnotically undulating alternating between E major and E minor. It can also be exciting for short periods, as in Madame Mao’s robotic revolutionary rhetoric. Yet it rarely sweeps the listener up.

In contrast to previous minimalists, Adams seeks to offset the orchestral stasis by introducing traditional melody in the vocal parts – which he does by adopting a surprising number of traditional bel canto conventions. Act I ends with an ensemble, Act II with a coloratura showpiece, and Act III with a reverie – and the opera even contains a ballet, albeit a surrealistic one reminiscent of a 1950s movie dream sequence. Each major character receives at least one big scena. President Nixon’s opening aria (“News”) follows the fragmented style of the orchestra, but in the second and third acts, the vocal lines become longer and more romantic – and are then often picked up by the orchestra in a manner intermittently reminiscent of Wagner or Puccini. Later in the opera, pop rhythms and ballet music appear.

This distinctive structure means that a successful performance of Nixon in China requires great singing actors. The justly celebrated premiere production, directed by Peter Sellars and featuring Boston-area stalwarts Janes Maddalena as President Nixon and Sanford Sylvan as Premier Chou En-lai, was exemplary. It also included a superb portrayal of Pat Nixon by the extraordinarily versatile crossover artist Carolann Page – who teaches today at Westminster College, less than a mile from where Princeton Festival performs.

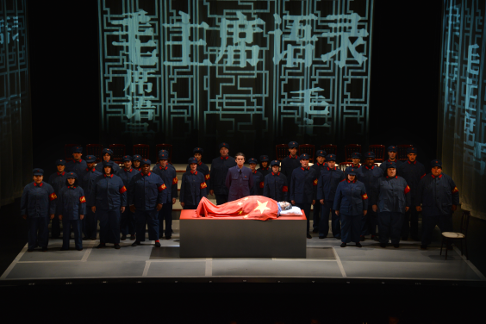

Death of Mao

Death of Mao

The Princeton cast was comprised of younger American singers with a solid track record in regional houses and on the competition circuit. Almost all excelled in what was the first time performing this difficult score. Baritone Sean Anderson, who has performed here several times before, blustered self-importantly as Nixon. Lighter baritone John Viscardi remained dignified and smooth in the lighter role of Chou En-lai. Coloratura Soprano Rainelle Krause reined in a few blaring high notes to offer a subtly characterized renditions of Pat Nixon’s big monologue. Soprano Teresa Castillo brought down the house with Madame Mao’s big rant, even if she lacks some of the icy precision and focus the score suggests. Tenor Cameron Schutza deployed a ringing Heldentenor to portray Chairman Mao. Baritone Joseph Barron was gruffly sonorous as Henry Kissinger. Each singer was precise and passionate and acted well.

A great performance of this difficult opera, however, requires more. Maximum impact requires singers able to deliver lines with the subtlety, exceptionally clear diction and clear and beautiful tone of a Lieder singer – something made easier by the use of microphones authorized by the composer. In general, the Princeton performance was more conventionally “operatic” that it might have been, and not all singers consistently attended to stylistic nuances.

One example must suffice. Unlike many modern composers, Adams writes with exceptional attention to poetic cadence. The note values in his vocal lines subtly mirror different patterns of long and short syllables. In particular, the ends of many lines are syncopated (most often LONG-short-LONG, or LONG-short-short). (An example is President Nixon’s first sung line: “News has a kind of MY-ster-Y”.) This distinctive three-syllable rhythmic snap drives the music forward – much as does the rap cadence in a more recent work like Hamilton.

Such details intermittently went missing, as one might expect in a short run. Achieving such stylistic unity requires, in addition to precise coaching, a conductor who keeps the orchestra moving swiftly and is willing to hold down the volume and weight of the instrumental playing. Festival Director Richard Tang Yuk directed with his customary care and precision, and the orchestra and chorus delivered a polished performance of this difficult work – even if cautious tempos, a thick sound, and intermittent lack of rhythmic nuance tended, in the end, to drag the performance down somewhat. The staging showed that much how much innovative lighting and color can achieve at a relatively low cost. The opening and closing scene, in which Chou stands before the casket of Mao, was particularly effective. The ballet dancers were engaging.

Overall, this production reinforces the Princeton Festival’s reputation as a site for innovative and sophisticated summer opera.

Andrew Moravcsik

image=http://www.operatoday.com/NiC003.png image_description=The Nixons and Kissinger [Photo courtesy of The Princeton Festival] product=yes product_title=The Princeton Festival Presents Nixon in China product_by=A review by Andrew Moravcsik product_id=Above: The Nixons and KissingerPhotos courtesy of The Princeton Festival

June 28, 2019

Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel at Grange Park Opera

But from our contemporary perspective it is difficult to make such a setting seem anything but picturesque, so opera directors have mined the psychological elements underlying the story. Two iconic 20th century productions, that of David Pountney for English National Opera and by Richard Jones for Welsh National Opera set the piece in urban 1950s with the wood and the witch representing a psychological nightmare based on reality.

Stephen Medcalf's production of Englebert Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel was shared between the Royal Northern College of Music (where it debuted last year) and Grange Park Opera, where we saw the second performance on Thursday 27 June 2019. Caitlin Hulcup was Hansel and Soraya Mafi was Gretel with Susan Bullock as Mother and the Witch, William Dazeley as Father, Lizzie Holmes as the Dew Fairy and Eleanor Sanderson-Nash as the Sandman. George Jackson conducted the orchestra of English National Opera.

Medcalf and his designer Yannis Thavoris set the piece in the 1890s with the family as urban poor, whilst the 'forest' is simply the outside city (Thavoris provided a striking forest of street lights) and foraging for the children consists of scrounging and stealing Oliver Twist-style. The witch's house is in fact a magic sweet shop, but its interior is a magically larger version of the children's home. All this would seem to provide some interesting psychological layers to explore, particularly as the production had Susan Bullock doubling as the Mother and the Witch.

In fact the urban forest entirely lacked a sense of danger and, populated during the Witches ride by a cast of Dickensian-type characters, seemed simply picturesque with the children remarkably in charge of their own destiny. Whilst the third act's setting in a version of the children's home had interesting resonances, none of this was explored as Susan Bullock's Witch was a magnificently comic creation which had little link, physical or metaphorical, to her performance in Act One as Mother.

The intention, as with the Royal Opera's disappointing recent new production of the opera seemed to be to provide an evening of unthreatening entertainment, and within these constraints Medcalf's production was surprisingly imaginative, and coupled to one of the finest musical performances of the opera that I have heard in a long time.

The musical delights started with the first notes of the overture as the horn melody rose out of the pit, rich in texture and beautifully shaped. George Jackson and the orchestra brought out the well-made counterpoint which underlies Humperdinck's score. Yes, the glorious melodies were there, finely phrased and, well, glorious. But weaving them together was a sense of this beautifully made German counterpoint, which showed the work's complex history. The orchestra of English National Opera seemed to be demonstrating what we were missing by not using a full orchestra for ENO's recent production of Hansel and Gretel at Regent's Park Open Air Theatre. And George Jackson, a young conductor to watch, was clearly alive to the various resonances in Humperdinck's score. Yes it is Wagnerian, but I also heard pre-echoes of Mahler in the Act Two folk-sequences. Throughout the amount of detail was wondrous, yet woven into an enchanting construction which mixed humour with the magical. The angel pantomime at the end of Act Two provided the element of transformative radiance, which was entirely lacking in Medcalf's lamp-lighter's ballet. Whatever other musical delights the production offered, and there were plenty, I kept coming back to Jackson and the orchestra.

Soraya Mafi and Caitlin Hulcup made a delightful pairing as Gretel and Hansel, for all the picturesque charm of the characters' depiction there was a fundamental seriousness to their performance which emphasised the music's quality. Mafi was a poised Gretel, shaping the lovely melodies carefully and expressively, and she was matched by Hulcup's wonderfully boyish Hansel (one of the best 'boys' I have seen in this opera for a long time), with the two voices blending and contrasting. They kept the action moving so that the scenes between them in the first two acts, which can sometimes drag somewhat, flew by.

There was a fundamental realism to Susan Bullock and William Dazeley's performances as Mother and Father which anchored Act One in the real world rather than magic or fairy-tale, and this vastly benefitted the performance. Both were well sung, providing rounded depictions rather than just sketched in 'characters'. Bullock was transformed in Act Three and her Witch was a gloriously comic creation, vocally commanding and delightfully outrageous.

Eleanor Sanderson-Nash's Sandman was a louche opium addict, a picturesque and nicely bohemian touch, whilst Lizzie Holme's charming Dew Fairy was in fact the milk-man. Both women looked unrecognisable in the male personae. The women from this year's ensemble at Grange Park Opera provided the children's chorus at the end, appearing from the oven as a fleet of refugees from Oliver Twist.

For some reason this was sung in German, when the accessibility of the production would have suggested using an English translation. But the cast's diction was excellent and all made Humperdinck's setting of the German tell.

George Jackson, the orchestra and the cast made this performance a musical delight which meant that the music transcended the rather picture-book nature of the production, giving us a highly musically literate and satisfying evening.

Robert Hugill

Hansel: Caitlin Hulcup, Gretel: Soraya Mafi, Witch / Mother: Susan Bullock, Father: William Dazeley, Dew Fairy: Lizzie Holmes, Sandman: Eleanor Sanderson-Nash; Director: Stephen Medcalf, Conductor: George Jackson, Designer: Yannis Thavoris, Lighting design: Jason Taylor.

Grange Park Opera, West Horsley Place, Surrey; 27th June 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Soraya%20Mafi%20%28Gretel%29%20and%20Caitlin%20Hulcup%20%28Hansel%29%20RHS.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Hansel and Gretel: Grange Park Opera 2019

product_by=A review by Robert Hugill

product_id=Above: Soraya Mafi (Gretel) and Caitlin Hulcup (Hansel)

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith

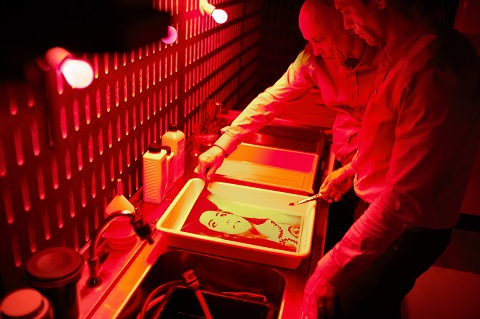

Handel’s Belshazzar at The Grange Festival

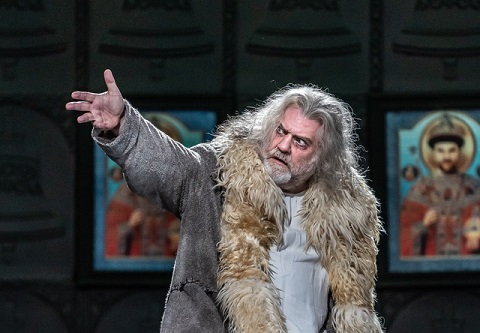

This is, of course, The Grange Festival’s production of Handel’s rarely staged oratorio Belshazzar. Kitted out variously in the guise of Babylonians, Jews and Persians and enhanced by The Grange Festival Chorus, The Sixteen along with their director Harry Christophers have been celebrating their 40th anniversary.

At a time of political uncertainty in Britain (alongside claims of anti-Semitism) and continuing unrest in the Middle East this production could not be more timely. The work’s opening soliloquy makes clear the transient nature of empire, comparing its deadly power to a monster that “robs, ravages and wastes the frighted world”. Sounds familiar? Oblique references to the current political climate this may be, but Handel’s dramatic oratorio may also have had striking contemporary resonances for the British people serving under a German monarch, George II, when it was first performed at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket, London in 1745.

In this performance in leafy Hampshire, a revolving model Tower of Babel and an intimidating defensive wall around the Babylonian city (just two of designer Robert Innes Hopkins’s imaginative creations) invoked notions of Trump Tower and controversial US border issues, yet these were more oblique references than heavy handed finger wagging. Handel’s setting of Charles Jennens’s libretto (he of Saul and Messiah) recounts the fall of Babylon and the liberation of the Jews by the conquering Persians whose diversion of the Euphrates (seen by Cyrus in a dream) allows them to access the city on a night of sacrilegious revelry. Pleas for Belshazzar not to violate the Israelite’s God go unheeded and a ghostly text predicts his downfall. Thanks to The Grange Festival’s artistic director Michael Chance this performance (not originally conceived for the stage) enabled an excellent team of soloists, the chorus and orchestra of the Sixteen to remind us of Handel’s wealth of theatrical instincts.

James Laing (Daniel) with the Sixteen and the Grange Festival Choruses. Photo credit: Simon Annand.

James Laing (Daniel) with the Sixteen and the Grange Festival Choruses. Photo credit: Simon Annand.

Under Daniel Slater’s imaginative direction this fully-fledged operatic conception included, in addition to the Brueghel-inspired Tower, three eye-popping acrobats whose perilous movements brought visual spectacle to Belshazzar’s lavish quarters and suggested that they, like the king and his sybaritic entourage, might be on the brink of disaster. Sharply delineated costumes neatly outlined national identities; brightly garbed party-set Babylonians, darkly clad Jews with traditional prayer shawls and, for the Persian army, military tunics straight out of Star Wars. Getting in and out of this attire was something of an achievement during one chorus where, in just a few bars, the marauding Persians morph into body-writhing Babylonians. That said, the Sixteen readily embrace these roles, entering into the spirit with undisguised relish and acting their parts as if born to them.

No less involved is Robert Murray’s impressively sung Belshazzar whose gilt-edged tenor dispatches demanding arias with ease and portrays a character whose excesses alarm and revolt. Clearly beyond the control of his long-suffering Nitocris, he is unrepentant after the Jewish prophet Daniel interprets the writing on the wall - a captivating scene bringing emotional trauma to both. Claire Booth is a richly characterised Nitocris, who brings clear cut credulity to a grieving and finally humiliated mother, her compassion and anxieties for her son movingly expressed in ‘Alternate hopes and fears distract my mind’. Only her romantic attachment to Daniel seems to a strike false note - one that reduces the honour of both parties and unnecessarily creates a degree of exaggerated melodrama. James Laing fashions a scholarly-looking Daniel and sings with reassuring eloquence, while Christopher Ainslie as a benevolent Cyrus dazzles more for his bravura rendition of ‘Destructive war, thy limits know’ while clinging onto the side of the ziggurat than his valour as a heroic champion of the Persians. By contrast, Henry Waddington’s son fixated Gobrias was sung with spirited vengeance.

What consistently claims attention is the discipline and vigour of the augmented chorus. The Sixteen bring emotional substance to their distinct roles (whether mocking, imploring or warmongering) and textural clarity to their contrapuntal lines. The score is driven along with a sureness of touch from the podium - Christophers drawing incisive, well-balanced orchestral playing, completely at home in this gem-filled score.

David Truslove

Belshazzar - Robert Murray, Nitocris - Claire Booth, Cyrus - Christopher Ainslie, Daniel -James Laing, Gobrias - Henry Waddington, Acrobats (Haylee Ann, Craig Dagostino and Felipe Reyes); Director - Daniel Slater, Conductor - Harry Christophers, Designer - Robert Innes Hopkins, Movement Director - Tim Claydon, Lighting Designer - Peter Mumford, The Grange Festival Chorus & The Sixteen.

The Grange Festival, Hampshire; Saturday 22nd June 2019.

Photo credit: Simon Annand

June 26, 2019

Kenshiro Sakairi and the Tokyo Juventus Philharmonic in Mahler’s Eighth

Famously, the Fourth, if not premiered first, was given the earliest recording by the New Symphony Orchestra of Tokyo under Hildemaro Konoye in May 1930; the Eighth was performed in Japan in December 1949, conducted by Kazuo Yamada, almost certainly the first time it was ever heard in the Far East.

There is a perfectly logical reason why Japan seems to have been so slow in embracing western classical music. In part, it is simply a factor of Japanese society which largely rejected outside cultural influences, especially before the Meiji Restoration of 1868. But what Japan lacked, which was not the case in either the United States or Europe, were music schools and decent orchestras to teach and play this music. Luther Whiting Mason, director of the Boston Music School, and the Munich-born Klaus Pringsheim, would both have a profound impact on the expansion of western music in Japan and its lineage through the twentieth century and onwards stretches from notable Mahler conductors beginning with Wakasugi, Kazuo Yamada, Akiyama and Ozawa through to Kobayashi and Inoue and a younger generation which includes Kazuki Yamada, Kentaro Kawase and Kenshiro Sakairi.

As an introduction to this new recording of Mahler’s Eighth, this diversion into the (briefest) of backgrounds is not strictly irrelevant because what we have here are the fruits of those earliest musical schools. The Tokyo Juventus Philharmonic doesn’t exactly think in terms of repertoire that is scaled down; in fact, all of its previous CDs have been of some of the most difficult and unforgiving works which would test many professional symphony orchestras. But then, this is not an ordinary youth orchestra, and Kenshiro Sakairi is a distinctly unusual conductor.

The Tokyo Juventus Philharmonic was founded in 2008 - originally under the name of the Keio University Youth Orchestra - and its first musicians were mainly high school students and members from the university. Today it has as many as 150 musicians. Like many western youth orchestras its repertoire is limited to a few concerts a year but what is particularly distinctive about the TJP is that it shares many of the characteristics of professional Japanese orchestras. That blended brass tone, the rich string sound, the distinctive woodwind phrasing and the precision of the playing are of an extremely high standard.

If there is a common thread which links youth orchestras it is often that the body of players is much larger than one would experience in most symphony orchestras we hear today in concert halls. Eight double-basses are the norm - not the thirteen we get in this Mahler Eighth. Arguably, the heft and weight, especially in the strings, probably doesn’t make this strictly necessary - listen to either recording of Sakairi’s Bruckner Eighth or Ninth and the richness of the cellos and basses, and even the violins, sometimes a weakness in many Japanese orchestras, makes for a thrilling sound, and would likely be so without the added strings. Sakairi is himself a patient conductor, one who takes his time over the music - it’s highly organic and is nurtured as such. The pauses and spaces he inserts between notes, the acknowledgement of bar rests, are more than a nod to a conductor like Celibidache, or even late Asahina.

It's certainly clear this is a musical partnership which is getting better - their Mahler Third, recorded in 2017, perhaps got lost in some parts, where a focus on orchestral beauty became a template for a loss of perspective elsewhere (though Sakairi is by no means the first conductor to be trapped by this symphony’s problems). On the other hand, an unreleased Mahler Second from a year earlier is tremendously powerful for quite the opposite reason - it sacrifices some orchestral beauty for an unswerving relentlessness and swagger. A Bruckner Ninth, from January 2018, is a colossal performance - it’s visionary, prepared with meticulous attention to detail, and yet so extraordinarily intense and fresh. This most recent recording of Mahler’s Eighth is at least as striking.

Although CD issues of Mahler Eighth have become more frequent - and in Japan there had been eleven prior to this recording - by a strange quirk, and less than a week after this Sakairi performance, another was given, by Kazuhiro Koizumi and The Kyushu Symphony Orchestra, and that, too, has just been released on Fontec. Can you have too much of a good thing? Well, yes and no. For many years, Takashi Asahina’s Osaka Philharmonic recording, performed in 1972, was the first and only one available - and it remains to this day one of the best from Japan. One could question the idiomatic accuracy of the singing - but what Asahina does with the symphony is often compelling. Yamada’s 1979 recording with the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra was done thirty years after his Japanese premiere of the work - and is the most detailed, perhaps most convincing performance to date. Others, like Wakasugi (who recorded the first complete Mahler cycle in Japan), Inoue and Kobayashi seem both overwhelmed and lost in the scale of this symphony. Of the two western conductors to have recorded with Japanese orchestras, Bertini has a narrow edge over Inbal.

Kenshiro Sakairi’s recording is incredibly detailed; in fact, it’s meticulously so in a way almost very few Mahler Eighth’s are. This orchestra and conductor’s precision - in the sense that every note is in place, the feeling that every facet of the score has been followed - works for and against them. When I first listened to this CD I was so blown away by the orchestra, their tone, the finesse and articulation of the woodwind, and the sheer opulence of the sound generated that the measure of the symphony’s scale rather eluded me. It’s only on a second listening I became fully aware of the electrifying performance that Sakairi gives. Quite how this would have worked in the concert from which this performance is taken is a question I have yet to definitively answer for myself.

As is common with most of the TJP/Sakairi recordings - most notably the superlative Bruckner Ninth - it is the singularity of the symphonic line, the ability to take this music in an arc which is so hugely impressive. I don’t think Sakairi takes his cue from many of the Japanese performances he probably grew up with - rather, the influence that seems most striking is that of Bernstein. He is only marginally slower than Bernstein’s LSO recording, though timings are deceptive. The pace Sakairi sets - and generally holds - is swift but the structure, whether in Part I or Part II, retains a formidable flow and smoothness, and I don’t mean smoothness in an ineffectual or unimposing way. The clarity of the variations in Part II, where many conductors sectionalise this symphony, isn’t patched together - it has a very fluid narrative. And if this is an orchestra with a powerful sound, the whole of the opening of Part II, that wonderfully mysterious orchestral prelude, is actually magical and haunting. There is much in this performance which suggests collision - but there is much which swings the opposite way towards heavenly enlightenment.

How far the pathos, or spirit of redemption, or even the profoundly complex journey into Faust’s soul, which is a powerful force in this symphony could, or might, confound a young orchestra or conductor, throws up some interesting contrasts with other recordings. Sakairi is barely over thirty; Asahina and Yamada were well into their sixties when their recordings were made. Few might expect a younger man to empathise so directly with the concept of mystery - yet, it’s here. It was there in his Bruckner Ninth. Yamada’s recording might be convincing in many respects, but it’s arguable thirty years after his premiere his vision of this symphony had changed. As was common with many Yamada performances in his later years, tempo could be wildly disjointed, and that is the case here. He speeds up, and slows down, with disturbing frequency. Asahina is perhaps more stable. But what disfigures both performances is the quality of the playing, which is erratic at best, and simply inferior at worst. Asahina is prone to take his time; Yamada tends to navigate a more ill-disciplined route.

Sakairi and the TJP play with quite sublime brilliance, and the recording exposes them to quite a high degree of scrutiny. As is common with many Altus CDs, the engineering is first rate - though perhaps some might find the choral forces a little recessed. The focus here can sometimes be very much on the orchestra and the soloists. That ‘exposure’ works in many ways: the orchestra can sound unusually dark (though I personally like their sound), the tendency to spotlight instrumental solos is often ravishing. The opening to the ‘Chorus Mysticus’ is astounding, mystical, hushed and deeply moving. How the chorus just floats above the orchestra and the soprano gently rises through them both is beautifully captured by the microphones. But to be able to not overblow the climax as well says much for both the careful attention to dynamics from Sakairi and the outstanding engineering.

What of the singing itself? It’s undoubtedly the case that in the past Japanese choirs and soloists have found German a problem; that is less true today. Most, if not all, of the singing on this Mahler Eighth is comfortably pronounced, and more so given the heady tempo which Sakairi sets for them. Is there enough contrast in the soloists? Yes, I think there is, especially in the trio of sopranos who sing with gorgeous precision and colour. Shimizu Nayutu, as Pater Profundis, is superb - a deep, rich bass, sounding suitably tortured. Likewise, Miyazato Naoki manages the high tessitura of Doctor Marianus with flawless technique. Both the NHK Children’s Choir and the Tokyo Juventus Philharmonic Choir are superb.

This is unquestionably the finest Mahler Eighth yet to emerge from Japan. However, I’d go a bit further than this - it leaves a lot of Mahler Eighths recorded in the United States and Europe rather in the shade as well. There is a blend of the orchestral and the vocal here, the redemptive and the dramatic, which is enormously compelling. It helps it has been captured in beautiful sound, but the performance is entirely gripping. Much of it is simply electrifying - many Mahler Eighths, rather elusively, aren’t. All in all, a magnificent disc.

Marc Bridle

Soprano 1 (Moritani Mari), Soprano 2 (Nakae Saki), Soprano 3 (Nakayama Miki), Alto 1 (Akira Taniji Akiko), Alto 2 (Nakajima Keiko), Tenor (Miyazato Naoki), Baritone (Imai Shunsuke), Bass (Shimizu Nayuta), NHK Tokyo Children's Choir (Choral Conductor: Kanada Noriko), Tokyo Juventus Philharmonic Choir (Choral Conductor: Tanimoto Yoshi Motohiro, Yoshida Hiroshi)

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mahler%208%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title= Gustav Mahler: Symphony No.8; Tokyo Juventus Philharmonic/Kenshiro Sakairi; ALTUS 012/3; recorded live 16th September 2018, Muza Kawasaki Symphony Hall, Japan; available from HMV Japan. product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=June 25, 2019

Don Giovanni in Paris

Et voilà, one of the great evenings in the theater. And yes, it was not subtle.

Conductor Jordan immediately pounced on the musical tensions that structure late eighteenth century music and did not let go. The ensuing, unrelenting drama from the pit creating the antagonism between Giovanni and Leporello, with Leporello cruelly rubbing in Giovanni’s sexual exploits to Elvira, Masetto angrily snapping at Zerlina, Giovanni coldly setting up the ambush of Leporello.

Don Ottavio took resolute charge of the vengeance to come, Giovanni brutally beat-up Masetto. Donna Anna, horrified at her aggressor, selfishly cruel to Don Ottavio. Elvira doggedly chased Giovanni, Giovanni focused full determination to seduce the perfect woman. Leporello, finally losing all patience with Giovanni, picked up the Commendatore’s dinner table and threw it across the room.

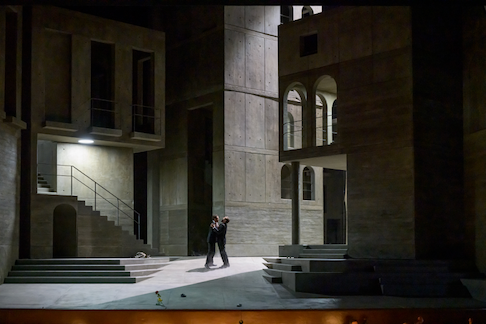

Don Giovanni and Leporello

Don Giovanni and Leporello

Giovanni went straight into the seething hell that had been leaking steam through the stage floor from the downbeat of the overture.

And, by the way, Mozart wanted three orchestras on the stage for the Act I finale. There they were, no room for much else, the country dance and the waltz chiming in with the minuet to create a quite Classical idea of cacophony to match the mess on stage.

This Don Giovanni is a gloves off release for all your pent up Don Giovanni hostilities. No wimpy Don Ottavio, no Freudian Donna Anna. No bumbling Masetto or cute Zerlina, no heroic or lonely or debauched Giovanni.

It was pure Mozart, and it was pure Don Giovanni, no questions asked.

Philippe Sly as Leporello impersonating Don Giovanni, Nicole Car as Donna Elvira

Philippe Sly as Leporello impersonating Don Giovanni, Nicole Car as Donna Elvira

To accomplish this musical and dramatic feat the Opéra de Paris assembled a very handsome cast indeed of fine, beautifully voiced young singers who confronted one another face to face when not nose to nose. Giovanni tall, slim and bearded, Leporello tall, slim and bearded (no Act II suspension of disbelief necessary), Donna Anna obviously very worthy prey, Masetto wiry, sharp witted and energetic, the Commendatore towering in presence and in voice.

Thus it is no understatement to say the the evening was an orgy of Mozartian phrasing, maestro Jordan’s orchestra sharply defining the musical parameters, carving out strategic dramatic plains against which the vocal lines etched themselves.

Étienne Dupuis as Don Giovanni, Mikhail Timoshenko as Masetto, Elsa Dreisig as Zerlina, Philippe Sly as Leporello

Étienne Dupuis as Don Giovanni, Mikhail Timoshenko as Masetto, Elsa Dreisig as Zerlina, Philippe Sly as Leporello

The unique colors of each of the voices defined its character — the suavity of the Don’s Act II serenade, the sophistication of Leporello’s “Madamina,” the narcissism of Donna Anna’s “Non mi dir,” the voluptuous of Donna Elvira’s “Mi tradi,” the confidence of Don Ottavio’s “Il mio tesoro” (though sung partly in fetal position), the free and easy sexuality of Zerlina’s “Vedrai carino.”

With a virtuosity and sense of phrasing surely equal to the voices designer Jan Versweyveld lighted his concrete walls, pulling out components of its geometric shapes in light and dark grey based colors, save the saturated gold that flooded the stage for the masked trio “Protegga, il giusto cielo.” Designer Versweyveld served as well as the dramaturg of the production.

Stage director Ivo van Hove and conductor Philippe Jordan created a production that took Mozart’s masterpiece to its bare bones with a myriad of hidden sophistications. This Don Giovanni is a daring creation of great wit and profound sensitivity to Mozart’s masterpiece.

French bass-baritone Etienne Dupuis was Don Giovanni, Canadian bass-baritone Philippe Sly was Leporello. American soprano Jacuelyn Wagner was Donna Anna, Australian soprano Nicole Car was Elvira. French tenor Stanilas de Barbeyrac sang Don Ottavio. Russian Mikhail Timoshenko and Franco-Danish Elsa Dreisig were the Masetto and Zerlina. Estonian bass Ain Anger sang the Commendatore.

Opera and theater director Ivo van Hove directs Kurt Weill’s The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny at the Aix Fesitival next month (July). Note that this Don Giovanni travels to the Metropolitan Opera next year. Conductor Philippe Jordan this summer again conducts the deconstructed Die Meistersinger at the Bayreuth Festival.

The understated, simple costuming for this production was created by An D’Huys, the impressive hell video was created by Christopher Ash.

I saw the fourth (June 21, 2019) of eleven performances.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Giovanni_Paris1.png

product=yes

product_title=Don Giovanni at Palais Garnier

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Jacuelyn Wagner as Donna Anna, Etienne Dupuis as Don Giovanni, Anger as Don Pedro (Donna Anna's father)[all photos copyright Charles Duprat, courtesy of the Opéra de Paris]

June 24, 2019

Lyric Opera of Chicago’s 2020 Ring Cycle

By the start of next spring’s cycles, the team of singers, musicians, and production staff will have worked together for an extensive period of four seasons, sufficient time to yield a collaborative effort of exciting potential. The Lyric Opera Orchestra will be led throughout by Its music director, Sir Andrew Davis, whose commitment to the works of Wagner has contributed markedly to the reception of the first three operas to date.

While the individual operas of the cycle have generated enthusiasm based on their specific artistic merits in Lyric Opera of Chicago’s recent productions, the opportunity to experience the totality of the Ring as a unified, continuous series will offer a rare event of collaborative forces. In Das Rheingold, the first opera or essentially the prologue to the following three operas, both devices and personalities forge a path into the forthcoming stories of love, power, and loyalties. The structural use of elevation, both mobile and stationary, has a binding effect that distinguishes specific scenes yet prompts the viewer to appreciate thematic and musical ties existing with the following operas. The Rhinemaidens hover aloft on mechanical lifts raised and lowered or propelled by supernumeraries as the maidens sing of the sun and gold. Their gracefully produced music undulates with the mechanized flow of the crane-like lifts. In subsequent scenes the giants emit their menacing bluster from atop moving towers. such a placement effectively emphasizing their power and size. Comparable yet stationary towering structures flank the stage in the following opera, Die Walküre, here used to indicate an oppositional relationship between the warriors Siegmund and Hunding. Once the identity of Siegmund becomes apparent in the first act, each warrior appears seated at the base of one of the opposing towers, each of these figures staring forward grimly in anticipation of future conflict. This battle takes place at the conclusion of the following act with either warrior positioned midway upon the respective, elevated structure, the gods and their kin intervening in the remaining space. In Siegfried the locale of the smithy in the forest is fashioned appropriately with flat lines, yet the development of the protagonist must transcend the realm of Mime and Alberich. In response to the elevated, coaxing calls of the Forest Bird, sung in last season’s new production with thrush-like intonations by Diana Newman, Siegfried, as performed by the impressive Burkhard Fritz, indeed follows an upward path until he reaches the sleeping Brunnhilde. Their joyous scene of burgeoning emotions is then celebrated on this raised portion of the stage. It will be exciting to trace further structural parallels in next season’s new production of Götterdämmerung and to anticipate comparable insights in the complete Ring cycles beginning in April 2020.

Lyric Opera of Chicago has assembled a superlative cast for this project, a team of singing performers associated both nationally and internationally with their respective roles. Perhaps most striking thus far has been the depth of character that the singers bring to their roles. Christine Goerke’s definitive Brunnhilde captures the excited involvement of a battle-maiden when assisting Siegmund, the wounded penitence of a disobedient daughter in her in her extended dialogues with Wotan, and the boundless promise of romantic love when awakened by the hero Siegfried. Likewise, the Wotan of Eric Owens moves from his adventurous complicity in Das Rheingold to the part of defensive mate and angry parent in Die Walküre, before taking an integral hand in Siegfried’s development in the following opera. Also returning in the complete cycle is the incomparable Stefan Margita, whose Loge in Das Rheingold propels the action and prepares the stage for subsequent confrontations in the following operas of the cycle. Tanya Ariane Baumgartner reprises her imperious Fricka in an elegantly idiomatic interpretation. Elisabeth Strid and Brandon Jovanovich create an unforgettably lyrical pair of siblings. Mathias Klink makes a tour de force of acting and singing as Mime, and Ronita Miller will perform her deeply felt and pivotal depiction of Erda.

Performances of the complete Ring cycle will take place in successive weeks with following schedule:

Cycle 1

Das Rheingold, Monday 4/13/20, 7:30 p.m.

Die Walküre, Tuesday, 4/14/20, 6:00 p.m.

Siegfried, Thursday, 4/16/20, 6:00 p.m.

Götterdämmerung, Saturday, 4/18/20, 5:30 p.m.

Cycle 2

Das Rheingold, Monday 4/20/20, 7:30 p.m.

Die Walküre, Tuesday, 4/21/20, 6:00 p.m.

Siegfried, Thursday, 4/23/20, 6:00 p.m.

Götterdämmerung, Saturday, 4/25/20, 5:30 p.m.

Cycle 3

Das Rheingold, Monday 4/27/20, 2:00 p.m.

Die Walküre, Wednesday, 4/29/20, 2:00 p.m.

Siegfried, Friday, 5/1/20, 2:00 p.m.

Götterdämmerung, Sunday, 5/3/20, 2:30 p.m.

Click here for additional information.

Click here for the text of Richard Wagner’s The Nibelungen-Myth. As Sketch for a Drama.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Chicago_Ring.png image_description=Image by Lyric Opera of Chicago product=yes product_title=Lyric Opera of Chicago’s 2020 Ring Cycle product_by=By Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above image courtesy of Lyric Opera of ChicagoIrish mezzo-soprano Paula Murrihy on Salzburg, Sellars and Singing

Sellars will return to the Salzburg Festival this summer to present a new production of Idomeneo. It reunites him with conductor Teodor Currentzis, following their acclaimed 2017 interpretation of Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito, which highlighted the opera’s vision of a path to democracy through restorative justice and reconciliation, and also with musicAeterna Choir of Perm Opera and tenor Russell Thomas as the eponymous king. Among the cast will be Irish mezzo-soprano Paula Murrihy who performed with Thomas when Sellars’ La clemenza was staged at Dutch National Opera in May 2018, and who will take the role of Idamante. I spoke to Paula on the eve of her departure for Salzburg to begin rehearsals.

Preparing for my conversation with Paula, I noted with surprise that it is ten years since I heard her sing - at the Wexford Festival in 2009 , where I enjoyed her performances as Cherubino in John Corigliano’sThe Ghosts of Versailles, Hélène in Chabrier’s Une education manqué (alongside Kishani Jayasinghe’s Gontran) and in recital with Irish baritone Owen Gilhooly, when songs by Brahms and Duparc were partnered by some Irish folk-songs and audience participation.

Such eclecticism has been characteristic of her career. And if her repertoire has been varied then so have the venues in which she has created these diverse roles. While she has performed in the UK - with English National Opera and at Covent Garden in 2014 for example - it’s on the international stage that she has largely forged her path - with Opéra de Nice, Santa Fe Opera, Opera Theatre Saint Louis, Los Angeles Opera, Oper Frankfurt, Opernhaus Zürich, Dutch National Opera, Oper Stuttgart, Chicago Opera Theater, and Boston Lyric Opera, to name just a few.

Paula’s travels began after her initial studies in Dublin, when she travelled to North America, for further study at the New England Conservatory. Subsequently, Paula participated in the Britten-Pears Young Artist Programme, San Francisco Opera’s Merola Program and was an apprentice at Santa Fe Opera. Paula explains to me that, having been ‘spotted’ when taking part in a competition in Germany in 2007, she joined Frankfurt Studio Opera in 2008 and a year later became a member of the Ensemble at Frankfurt Opera, where she remained until deciding to become a freelance singer two years ago.

Her time in Frankfurt gave her the opportunity to sing many roles at the right time for her voice. It also meant that she didn’t get ‘pigeon-holed’ in a particular genre and was able to explore a wide-ranging repertoire. She recalls one three-day period when she sang Medoro in Vivaldi’s Orlando Furioso on Friday, transformed herself into Mozart’s Dorabella (Così) the following evening, and then took a role in Parsifal (Flower Maiden) on Sunday! Alongside ‘central’ repertory such as Der Rosenkavalier, Hänsel und Gretel and Carmen, she had the opportunity to explore the operatic fringes, taking the roles of Lazuli in Chabrier’s L’étoile and Kreusa in Aribert Reimann’s Medea.

Being an Ensemble member brings security, of course, but as Paula points out companies are themselves protean entities, and two years ago the time seemed right for some changes, professionally and personally, as she wanted to spend more time at home in Ireland. 2017 saw her make her debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, as Stéphano in Roméo et Juliette, and return to Santa Fe Opera as Ruggiero in Alcina and as Die Fledermaus’s Orlofsky. And, in April 2018 she appeared at the Teatro Real Madrid for the first time - as Frances, Countess of Essex in David McVicar’s production of Gloriana.

Recently, UK audiences have had the opportunity to enjoy Paula’s performances. In January this year she sang Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen with the Britten Sinfonia and Sir Mark Elder, and recently appeared in recital at Wigmore Hall with Malcolm Martineau. Performing on the recital platform is clearly something that Paula is keen to do more regularly. She studied lieder and French song during her time as a Britten-Pears Young Artist, with Martineau, Ann Murray and Robert Tear, and tells me that she loves these “miniatures”: “There are so many eras, so many worlds, so many voices … it’s an enormous amount of work learning a recital programme, but immensely rewarding. Together with the pianist the singer has to create an entire world: it’s a collaborative journey during which this world has to be imagined - there’s a lot of thinking! - then brought into being, then let settle. And, in performance there’s always an intimacy between singer and audience, even if the concert hall is large; the audience have to come to the singer and take in the different worlds created.”

But, first comes Idomeneo in Salzburg. Sellars’ has spoken about his new production : “One passage in the libretto reads: ‘Saved from the sea, I have a raging sea, more fearsome than before, within my bosom. And Neptune does not cease his threats even in this.’ That is what Mozart’s music is about.” Remarking that the Greeks’ pride in winning the Trojan War was self-deceiving and foolish - “on the way home, the ocean said: No, you didn’t win. Everybody lost. And the ocean started breaking their ships apart” - Sellars imagines Idomeneo as “the opera that describes the angry oceans, what it means to negotiate with the oceans for the future of the next generation.”: “where we are with global warming is exactly where Mozart was with this opera: an older generation still not getting it, and a younger generation already on the case in very exciting ways.”

While Paula is still to learn of the details of Sellars’ conception, she knows that the director sees a ‘radicalism’ in the work and the elements of youth and sacrifice will be highlighted. She’s certainly “open to any ideas”. One element that does strike me as interesting and potentially controversial is Sellars’ decision to excise much of the recitative, something that he also did in La clemenza di Tito into which he interwove other music by Mozart, such as the Mass in C minor and the Masonic Funeral Music. In Sellars’ words, “the music is orchestral from beginning to end. Which means that the usual quality of these Enlightenment operas - the fact that everybody explains what they’re about to do before they do it - is gone. The audience has no idea why people are doing anything. So, it becomes much more like a movie: you’re plunged into the situation. It creates suspense.”

Having sung the role of Sesto when Sellars’ production of La clemenza was seen at Dutch National Opera, Paula is familiar with this practice. Interestingly, just a few months before, in October 2017, she had sung the role with the Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century and Cappella Amsterdam at the Concertgebouw, in a semi-staged performance. One could “hear every word of the recitative,” she explains, which, through text and gesture, created a “beautiful intimacy between Sesto and Tito”. The Sellars/Currentzis production, during which Paula was on stage for almost the entire performance, was a very different experience but one which she “adored”, valuing Sellars’ belief and integrity. And, she appreciates what Sellars was trying to achieve. She explains that in Idomeneo the omission of the opening recitative means that Idamante’s first line is ‘It’s not my fault’: “There’s a big backstory to create, and a narrative of love”. In any case, she laughs, apparently Mozart wasn’t that keen on recitative either and wanted to cut back!

It’s not Paula’s first appearance at the Salzburg Festival. She performed the Second Lady in Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte in July 2018, alongside Matthias Goerne, Mauro Peter, Christiane Karg and Albina Shagimuratova, in a staging by American director Lydia Steier and with Constantinos Carydis conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. It’s a role which she has sung many times before, and it was her first role at Frankfurt. Paula reflects that while it’s nice to repeat a role, she also loves learning new parts - she is soon to sing her first Donna Elvira with Orchestra of the Eighteenth Century, for example. I ask her if she has any particularly strong ‘musical leanings’, and she replies that she has an affinity for the Baroque, which has always seemed to her to share certain elements with Irish folk music. An improvisational quality, I wonder, or the primary of the voice? Paula suggests that the colours and clarity of the two genres seems in accord, and that there is a certain “vulnerability” which is present in both Baroque opera and Irish folk song.

She also especially likes singing in French, both in recital and in opera, as she feels that the language particularly suits her voice. At the end of the year she will sing Faure’s Pénélope for the first time, in Frankfurt, and looking ahead she would love to have the opportunity to sing Charlotte (in Massenet’s Werther) or Marguerite (in Berlioz’ La damnation de Faust). Opera casting agents, take note!

But, to return to the present, it’s the end of a long day, during which the next day’s travel plans seem to have unravelled! Despite this, Paula is generous, warm and self-effacing during our conversation. And, she’s obviously keen to begin rehearsals for Idomeneo. Reading about Sellars’ and designer George Tsypin’s plans to project images onto the rock walls of the Felsenreitschule throughout the opera, “floating up, floating down across this entire surface”, and at the end to “flood” the entire stage - “incredible footage of the plastic that is destroying the ocean right now and is in every one of our bloodstreams at this moment … will be projected onto the stone [here] - which is transformed into an underwater ruin” - one imagines that it’s going to be an exciting and thought-provoking experience.

Peter Sellars’ new production of Mozart’s Idomeneo opens the Salzburg Festival on 27th July.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Paula%20Murrihy%20Barbara%20Aum%C3%BCller.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Paula Murrihy sings Idamante in Peter Sellars’ new production of Idomeneo in Salzburg product_by=An interview by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Paula MurrihyPhoto credit: Barbara Aumüller

A riveting Rake’s Progress from Snape Maltings at the Aldeburgh Festival

On the way he discards the ever faithful and appropriately named Anne Trulove and succumbs to the temptations of Nick Shadow in the guise of the devil whose news of a windfall inheritance catapults Tom to a dissolute life in London where he marries the bearded Baba-the-Turk, plunges into a financially ruining bread-making scheme and, after defeating his alter ego at cards, dies grieving for his beloved Anne in an asylum.

Grim stuff, but it’s an opera suited to the talents of young singers who in this case were hand-picked musicians belonging to Barbara Hannigan’s Equilibrium Young Artists - a mentoring initiative for young professional musicians created in 2017 and here at Snape making their UK debut. This Rake’s Progress was the grand finale of a series of European performances which had been launched in Sweden at the end of last year. The production has been a semi-staged affair from the start and any potential issues over balance and space that might have been perceived in advance at Snape (where all the players and singers occupy a single performance area) were immediately dispelled. That said, Linus Fellbom’s directorial note in the programme book indicating the use of a performing ‘box’ (used in earlier outings) had to be ignored; this production left the performers free rein to use the stage directly in front of the orchestra. Of course, much was left to the imagination so that Mother Goose’s brothel and Sellem’s junk-filled auction were left to the mind’s eye. But with acting and singing as distinguished as this, there was little needed in the way of visual signposting to hold the ear and eye. Without pauses for scene changes the action rattled along with obliging swiftness.

That’s all credit to Hannigan (whose opera conducting debut this is) and Fellbom who, in the absence of any set and props (not forgetting much atmospheric lighting) provided sharply defined characters helped by some thoughtfully conceived costumes - Tom ironically dressed in ‘pure’ white and everyone else, including the innocent Anne, chorus and on-stage orchestra, clad in funereal black with gender fluid overtones for Shadow, whose culotte-like trousers might as well have been a skirt.

The cast was led by the young Welsh tenor Elgan Llŷr Thomas as the feckless Tom, whose brightly lit tone swept through the score from the opening duet through to “death’s approaching wing”. Able to command facial expression with ease, whether shame, frustration or child-like naivety when incarcerated in Bedlam, Thomas gave a truly persuasive portrait and his attempt to define love was particularly touching. There was no lack of chemistry between him and Greek soprano Aphrodite Patoulidou as a pure-toned Anne Trulove. Notwithstanding a slightly pressured Act 1 ‘Quietly night’ (here just slightly too fast to be as poignant as it can be), her Cabaletta had just the right steely determination and her closing lullaby, ‘And no word from Tom’, wonderfully tender, its heartbreak delivered the evening’s emotional climax.

Guadalupen-born Yannis Francois gripped throughout as the flamboyant Nick Shadow, a gentlemen’s gentleman whose ample baritone and insidious presence peaked in a compellingly wrought card game. Of the remaining cast, Fleur Barron was a generously hirsute and idiosyncratic Baba the Turk, James Way a confident man-about-town Sellem and Antoin Herrera-Lopez Kessel doubled as a timid but sympathetic Father Trulove and androgynous Mother Goose. A meticulously prepared chorus excelled as whores and roaring boys, auction bidders and madmen, and strikingly taut instrumental support came from the Ludwig Orchestra whose players (including Edo Frenkel on the harpsichord) brought much luminous detail to Stravinsky’s chugging rhythms and spiky outlines - the whole dispatched with Mozartian clarity. Praise too must be heaped on Hannigan whose incisive direction and unflagging pace electrified from the start, her minimal gestures sparking life into those opening fanfares and her keenly sensitive ear securing an ideal balance between her vocal and instrumental forces. In short, Hannigan and Fellbom nailed this unstaged Rake to release its emotional energy with dramatic power. Among the outstanding singers of Equilibrium are stars in the making.

David Truslove

Tom Rakewell - Elgan Llŷr Thomas, Anne Trulove - Aphrodite Patoulidou, Nick Shadow - Yannis Francois, Baba the Turk - Fleur Barron, Sellem - James Way, Father Trulove / Keeper of the Madhouse/Moose Goose - Antoin Herrera-Lopez Kessel, Director/Design/Lighting - Linus Fellbom, Conductor - Barbara Hannigan, Ludwig Orchestra & Chorus of Opera Holland Park.

Snape Maltings Concert Hall; Thursday 20th June 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BH%20Musacchio%20Ianniello.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Rake’s Progress: Snape Maltings Concert Hall, Aldeburgh Festival 2019 product_by=A review by David Truslove product_id=Above: Barbara HanniganPhoto credit: Musacchio Ianniello

June 21, 2019

The Gardeners: a new opera by Robert Hugill

‘A Soldier’s Cemetery’, bridging past and present and future, as imagined by Sergeant John William Streets, who was killed and missing in action on 1 st July 1916, aged 31.

The lands where the ‘fallen’ rest summon strong emotions: sorrow, shock, nostalgia, disbelief, anger. From the fields of Flanders where, in the words of John McCrae, ‘the poppies blow/Between the crosses, row on row’, to Owen Sheers’ Mametz Wood, where ‘For years afterwards the farmers found them -/ the wasted young turning up under their plough blades … A chit of bone, the china plate of a shoulder blade,/ the relic of a finger, the blown/ and broken bird’s egg of a skull’, the landscapes which are ‘home’ to those who gave their lives in war seem to resonate with the words of the dead as they try to speak, through the earth, to the living. Having visited the British War Cemetery at Bayeux, Charles Causley wrote:

I walked where in their talking graves

And shirts of earth five thousand lay,

When history with ten feasts of fire

Had eaten the red air away.

If such places are redolent with elegy and emptiness, rage and nostalgia, it is almost painful - in these troubling political times, at home and abroad - to remind ourselves that much of British history is built upon conflicts waged overseas. But, the gardeners who tend the cemeteries maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission honour the fallen as a labour of duty and love, ensuring that the 1.7 million people who died in the 20th century’s two World Wars are remembered. The Commission maintains cemeteries and memorials at 23,000 locations in 153 different countries.