July 31, 2019

Munich Opera Festival: La fanciulla del West

Whether in the pit or on stage, we were in hands far better, far more musical, than ‘safe’. One would have to travel far and wide to hear superior orchestral playing in Puccini, or indeed anything else, than from the Bavarian State Orchestra - and even then, one might well fail. Its lengthy experience in Wagner truly paid off, the composer’s renewed - not that it ever really vanishes - fascination with Tristan und Isolde there for all to hear: not just as superficial similarity, but as something more generative. For that and much else, the incisive, comprehending conducting of James Gaffigan deserves high praise indeed. Equally apparent here, especially in darker passages, was the related yet distinct haunting of Pelléas et Mélisande and, more broadly, Debussy’s music. It was Allemonde above all, though, that seemed to inspire the (apparent) workings of fate. Gaffigan captured to a tee the ‘American’, almost Gershwin-like character of the opening bars, proving himself - and the orchestra - distinguished guides to all of the score’s twists, turns, and transformations in between.

The principal trio of singers proved equally distinguished, unquestionably Wagnerian guides to the work’s course. Anja Kampe was, thank goodness, no goodie-two-shoes Minnie. In a more flesh-and-blood portrayal than I recall, this was a conflicted woman with, yes, much good in her, but also a beating heart that could take her to places unsafe, unwise, maybe even unwarranted. More than once, I was put in mind of her Kundry ( with Daniel Barenboim, in Dmitri Tcherniakov’s magnificent production ). I seem endlessly to repeat myself when it comes to performances from Brandon Jovanovich. I am certainly not prepared, however, to vary just for the sake of variation. His performance as Dick Johnson was everything we have come to expect from this intelligent, committed artist, as dramatically powerful as it was verbally acute, as sweet-toned as it was virile. John Lundgren’s Jack Rance was just as impressive: dark, malign, but also comprehensible, no cardboard-cut-out villain. From a fine supporting cast, I should single out Tim Kuypers’s Sonora. I do not think it is just the human agency of the role that has me do so; Kuypers made one feel there was considerably more to it than that.

Andreas Dresen’s production of La fanciulla del West premiered in March this year. (The opera’s first Munich outing, intriguingly, came in 1934, the city by then well and truly the Hauptstadt der Bewegung .) It does not do anything especially interesting with the work, but nor is it unthinkingly ‘traditional’, for want of a better word. A darker setting - literally, as well as metaphorically - is provided for the action, perhaps most notably for the first act at the Polka Bar. Mathias Fischer-Dieskau’s set designs, Sabine Greuning’s costumes, and Michael Bauer’s lighting are very much part of this. There were times when I wished for something more probing, more critical, but at least Dresen steers well clear of the folkloric. For my reservations remain concerning the work itself, more precisely its dramaturgy, and I cannot help but wonder whether a director might fruitfully contribute something more here.

Some are doubtless more important than others. One can get worked up about the racism. It is well-nigh impossible for a thinking person in 2019 not at least to cringe. But I am not sure that it especially helps, unless one childishly rejects all art of the past on the grounds that it is not of the present. Perhaps, though, something more might be done to address the issue. It certainly is not here - but then, alas, Puccini tends more than any other opera composer of stature to suffer from a lack of critical stagings. The somewhat sprawling nature of the first act perhaps invites greater intervention than we found here.

It is the close, however, that seems most urgently to invite a more critical stance. If I find the happy ending unconvincing - Puccini is surely better dealing with tragedy, and that includes the hollowest of victories in Turandot - then that must, at least in part, pay tribute to the expectations the composer has set up and indeed to his playing with them. I wish Dresen had donea little more with the possibility of undermining that ending. Jack’s fumbling reach for his gun is at best half-hearted; then the curtain comes down, separating Minnie and Dick from the rest. Nor do I think the score escapes charges of sentimentality here. No matter: it is what it is, and perhaps one day I shall come to appreciate it as many others clearly do. For now, the magnificently vile sadism of Turandot will continue to work its magic. Puccini’s wish for a ‘second Bohème, only stronger, bolder, and more spacious,’ seems to me unrealised. Fanciulla is perhaps bolder, if only in aspiration; it is certainly more spacious, if not to its benefit; it is hardly stronger. There was no doubting, however, the strength of these musical performances; in many respects, that was enough for now.

Mark Berry

Giacomo Puccini: La fanciulla del West

Minnie - Anja Kampe, Dick Johnson - Brandon Jovanovich, Jack Rance - John Lundgren, Nick - Kevin Connors, Sonora - Tim Kuypers, Trin - Manuel Günther, Sid - Alexander Milev, Bello - Justin Austin, Harry - Galeano Salas, Joe - Freddie De Tommaso, Happy - Christian Rieger, Jim Larkens - Norman Garrett, Ashby - Bálint Szabó, Wowkle - Noa Beinart, Billy Jackrabbit - Oleg Davydov, Jake Wallace - Sean Michael Plumb, Jose Castro - Oğucan Yilmaz, Pony Express Rider - Ulrich Reß; Director - Andreas Dresen, Conductor - James Gaffigan, Set Designs - Mathias Fischer-Dieskau, Costumes - Sabine Greunig, Lighting - Michael Bauer, Dramaturgy - Rainer Karlitschek/Lukas Leipfinger, Bavarian State Opera Chorus, Bavarian State Orchestra.

Nationaltheater, Munich; Friday 26th July 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/John_Lundgren-Anja_Kampe%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Munich Opera Festival: La fanciulla del West product_by=A review by Mark Berry product_id=Above: John Lundgren and Anja KampeRossini’s La Cenerentola at West Green House Opera

Making the best of limited stage facilities, Richard Studer shrewdly adopts a one-size-fits-all design which neatly amplifies the contrasting fortunes of, and social distinctions between Don Magnifico and his daughters and Prince Ramiro, his tutor and valet who, together, shape over two hours of comic interaction, the whole given slick, clear-sighted direction by Victoria Newlyn.

This new production manages not just to point up clear-cut class difference outlined by Jacopo Ferretti’s libretti (drawn from Charles Perrault’s tale Cendrillon) but wittily brings into focus unfulfilled social aspirations notwithstanding the central rags to riches narrative of Cinderella. We meet her stepfather Don Magnifico near the beginning of Act One emerging sleepily from his abandoned car around which his loutish daughters Clorinda and Tisbe torment Cinderella with cooking and cleaning chores. An image of the family’s former home is shown backstage, so too a palatial residence but, owing to limited resources, any lavish ballroom scene is left largely to our imaginations - as are the voices of the Chorus which arrive pre-recorded.

Sioned Gwen Davies (Tisbe), Heather Lowe (Cinderella) and Zoe Drummond (Clorinda)

Sioned Gwen Davies (Tisbe), Heather Lowe (Cinderella) and Zoe Drummond (Clorinda)

Rather than being short-changed by this specially tailored staging (along with Jonathan Lyness’s slimmed-down orchestral score) this made-to-measure version emphasises with potent immediacy the personal relationships of a cast of seven who, mostly at the start of their careers, provide strongly defined performances. Leading the young team, Heather Lowe made a wholly sympathetic Cinderella, no lily-livered personality here but a spirited young woman burdened by her lot without being entirely submissive to it. Vocally she was a joy to listen to, assured from her first folk-like ballad through to her enraptured final aria. On the way she combined an easy command of the role’s extended tessitura with a vocal agility that made room for plenty of expression no more so than her pleas to attend the prince’s ball. Hers was a voice that dispatched her multitudinous notes with an effortless facility, yet always placing technique at the service of the music.

Heather Lowe (Cinderella) and Filipe Manu (Ramiro).

Heather Lowe (Cinderella) and Filipe Manu (Ramiro).

She fashioned a believable partnership with New Zealand-Tongan Filipe Manu as the urbane Ramiro whose pleasing lyric tenor made light work of Rossini’s vocal demands, though his stage movement didn’t always convince in his dual roles as servant and prince. That said there was much to admire in his collaboration with Nicholas Mogg’s flamboyant Dandini attired in kilt and mismatching socks, and clearly revelling in his comic creation. Possessed with a clear, well projected voice, Mogg consistently held the ear and eye. His will be a name to watch out for.

Matthew Stiff (Don Magnifico), Filipe Manu (Ramiro), Blaise Malaba (Alidoro) and Nicholas Mogg (Dandini).

Matthew Stiff (Don Magnifico), Filipe Manu (Ramiro), Blaise Malaba (Alidoro) and Nicholas Mogg (Dandini).

Matthew Stiff also had stage presence as Don Magnifico, a role both comic and cruel, and sung here with a vocal warmth that brought plenty of appeal to his ‘used-car salesman’ characterisation. His daughters, Zoe Drummond’s Clorinda and Sioned Gwen Davies as Tisbe, were superb as bickering siblings; to the manor born as chavvy teenagers whose attempts to win the hand of Ramiro made for some truly cringe-making moments - a compelling coupling. Finally, there was the sobering presence and rich tones of the young Congolese bass Blaise Malaba.

Cast of La Cenerentola at West Green House Opera.

Cast of La Cenerentola at West Green House Opera.

Some of the most impressive musicianship came from the ensemble numbers where meticulous rehearsal paid off in assured performances occasionally supported by cheesy dance movement. Not exactly ‘Strictly’, but the disco-influenced routines were all part of this fun-filled evening. Giving support to those above stage was the West Green House Opera Orchestra skilfully directed by Matthew Kofi-Waldron. He secured stylish playing throughout and steered well-judged tempi that brought buoyancy and plenty of excitement without compromising ensemble. Altogether, a thoroughly enjoyable evening.

David Truslove

Cinderella (Angelina) - Heather Lowe, Ramiro - Filip Manu, Dandini - Nicholas Mogg, Don Magnifico - Matthew Stiff, Clorinda - Zoe Drummond, Tisbe - Sioned Gwen Davies, Alidoro - Blaise Malaba; Director - Victoria Newlyn, Conductor - Matthew Kofi-Waldren, Designer - Richard Studer, Lighting - Sarah Bath, West Green House Opera Orchestra.

West Green House Opera, Hook, Hampshire; Saturday 27th July 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Title%20WGOH%20Cinderella.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Rossini’s La Cenerentola at West Green House Opera product_by=A review by David Truslove product_id=Above: Heather Lowe (Cinderella)All images courtesy of West Green House Opera

July 30, 2019

Proms at ... Cadogan Hall (2): A Barbara Strozzi celebration

And, it was with a ground bass - a descending four-note chaconne - that we started, the delicate whispers of Monica Pustilnik’s archlute and Quito Gato’s theorbo articulating the opening bars of Strozzi’s, ‘L’amante segreto’, as the musicians of Cappella Mediterranea processed slowly onto the Cadogan Hall stage. The texture gently expanded, rustling chords and soft ornament filling out the hypnotic revolving circles of the bass line, in anticipation of the singer’s lament. With the accompaniment still a pianissimo elaboration, Mariana Flores entered from the opposite side of the Hall, slowly, with gravity, taking her place at the centre of the ensemble, her figure poised but her head bowed, seemingly physically burdened by the pain of unrequited love.

“Voglio morire”: I want to die. The opening line, derived from the bass and recurring throughout the madrigal, was a wisp of sound, clear but gossamer, a melancholic fall. Later Flores would reiterate this intent in more florid fashion, her yearning deepened by the dissonant pungency of clashing semitones and the darkness of director Leonardo García Alarcón’s weighty organ. The journey to such expressive peaks was a masterpiece of vocal and textual expression - from both Flores and Strozzi. The melody is intensely rhetorical, its curves and twists now fluid, then halting, and the Argentinian soprano controlled the contour of the line with exquisite subtlety. The long melismas quivered with feeling, then flowed in creative outpourings of emotion in a quasi-improvisatory fashion; and this improvisatory quality became more prominent with recorder player Roderigo Calveyra’s elaborations which injected pace and passion when the poet-singer finds new strength, rising from her frozen winter into a greener spring. At times, the disturbance created by sudden shifts in tempo and changes of metre gave way to the stillness of a monody which was rapturously communicative.

This mesmerising opening set the tone for the recital which was notable for its sustained intensity, deep sentiment and consummate musicianship. Propelled similarly by a bass ostinato, Strozzi’s ‘Che si può fare’ adds a prominent and dark-coloured viola da gamba to the piquant dissonances of harp (Marie Bournisien), archlute and guitar, and Margaux Blanchard’s low countermelody engaged with the vocal line with fluency and eloquence, matching the flexibility and inventiveness of Flores’ flowing line. Countering the wistfulness of hopeless reflections - “Che si può fare?”, “Che si può dire?” (What can anyone do?, What can anyone say?) - were Calveyra’s inter-verse cornett songs, played with a wonderful fullness and warmth that got inside one’s skin in the best possible way. But, despair turned to rebelliousness and resolve at the close. Flores imbued her voice with strength and a hint of flamboyance: the final cadence came suddenly, with a parting flourish like a vocal stamp of the foot.

‘Sino all morte’ is a longer, free-flowing cantata from Strozzi’s Diporte di Euterpe (The Pleasures of Euterpe). Published in 1659, its dedication to the future Doge Nicolo Sagredo described the contents as ‘lingue dell’ Anima ed istrumente del core ... come Sirene entro mari di Gratie’ (language of the soul and instruments of the heart ... like Sirens among a sea of Graces). Operatic in scale and passion, ‘Sino alla morte’ reflects on love consummated, unrequited, denied and destroyed, and Flores negotiated the sudden changes of mood and style, from impassioned elaboration to controlled declamation as superbly as she delivered the ever more complex fioritura, relishing its unpredictability. Similarly, in ‘Lagrime mie’ she exploited every melodic angularity, piquant chromaticism and fragmentation of the text to communicate the distress of the poet-speaker whose beloved Lidia has been imprisoned by her father. The sequences built a compelling dynamism, voice and bass intertwined beautifully, and every ounce of the lament’s meaning and feeling was brought forth with exquisite delicacy.

We also heard works by Strozzi’s younger Venetian compatriot, Antonia Bembo, who left Italy for France. There she gained the patronage of King Louis XIV who rewarded her with a pension which allowed her to stay in the community of Notre Dame de Bonne Nouvelle before moving to what she called a ‘holy refuge’ - the community of the Petite Union Chrétienne des Dames de Saint Chaumond. A dedicatory letter to her royal patron introduces Bembo’s collection of vocal pieces, Produzioni armoniche, a varied set of pieces which were intended for both sacred and secular performance. At the start of the aria ‘M’ingannasti in verità’, the harpsichord was restless and agitated, burning with betrayal, and Flores’ vocal line seemed to turn around and around on itself in bitterness. An elaborate, spirited recorder interlude whipped up the fury of the second stanza, where the rapid virtuosities flashed with fiery anger as the voice climbed ever higher. “Brava!” cried one delighted audience member above the applause. Calveyra displayed equal virtuosity in Bembo’s ‘Volgete altrove il guardo’ in which the vocal line was transcribed for recorder, playing with uneffusive calm but creating diverse colours, infectious energy and sunshine happiness at the close.

Both Strozzi and Bembo were taught by Francesco Cavalli and the latter’s ‘E vuol dunque Ciprigna’ allowed Flores to demonstrate her rhetorical skills, as she flew through the dramatic recitative communicating the rich sounds of the texts with precision and power, accompanied by unpredictable, sometimes almost violent, textures and harmonies.

This was an outstanding demonstration of the expressive union of words and music achieved by Strozzi and her contemporaries. Might Cappella Mediterranea have occasionally loosened the rhythmic strings a little and found rather more freedom to balance the earnestness? Might Flores have sought some of the irony in Strozzi’s texts, to counter the passion with a little playfulness? Perhaps. But, Flores sang with a boldness that was surely the equal of Strozzi’s own. And, we certainly experienced the ‘language of the soul and instruments of the heart’.

Claire Seymour

Proms at … Cadogan Hall 2: A Celebration of Barbara Strozzi

Mariana Flores (soprano), Leonardo García Alarcón (harpsichord/organ/director), Cappella Mediterranea

Barbara Strozzi - ‘L’amante segreto’, Antonia Bembo - Produzioni armoniche: ‘M’ingannasti in verità’, Strozzi - ‘Che si può fare’, Bembo - Produzioni armoniche: ‘Volgete altrove il guardo’, Strozzi - ‘Sino alla morte’, Francesco Cavalli - Ercole amante: ‘E vuol dunque Ciprigna’, Strozzi - ‘Lagrime mie’

Cadogan Hall, London; Monday 29th July 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Mariana%20Flores.png image_description= product=yes product_title=Proms at … Cadogan Hall (2): Cappella Mediterranea and Mariana Flores product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Mariana FloresPhoto credit: Jean-Baptiste Millot

July 28, 2019

Sublime Bohemians Captivate Indianola

This handsome physical production by set designer Robert Little was a worthy revival from the 2011 season. While Mr. Little may break no real new visual ground, he does splendidly fill the stage with three beautifully dressed and imposing settings that effectively satisfy all our sentimental, dreamy images of an idealized bygone Paris. If I had one wish, I would have loved for the transition from Act I to Act II to have been shorter. That said, when the curtain rose on Act II’s overwhelming, over populated Monmartre street scene, the revelation was greeted with appreciative applause that reveled in the scenic accomplishment.

Sarah Riffle lit the proceedings with an admirably calculated design that found great nuance between indoor and outdoor settings as well as varying times of day. From the warmth and joyous colorings in the palette for the first two upbeat acts, Ms. Riffle transitioned most effectively to cooler tones when the lovers’ troubles have set in. Her eventual moody illumination as tragedy visits the garret had meaningful impact.

Heather Lesieur effectively coordinated a truly lovely and large set of period costumes provided by Malabar Ltd. All festival long, Brittany Crinson’s make-up and hair designs were exemplary, and this emphatically proved true once more for La bohème.

In the best sense of the word, this was a decidedly traditional approach, some might even say “old fashioned.” I am always reminded that when a critic sniffed that “Annie, Get Your Gun” was old-fashioned, composer Irving Berlin retorted: “Yeah, an old-fashioned smash!” And so it is here.

“Team Bohème” has trusted the surefire material and eternal appeal of the melodious score and did everything possible to frame it beautifully and stage it with exuberant freshness. Director Octavio Cardenas has brought an abundance of imaginative stage business to bear, all the while he skillfully accommodates the time honored performance traditions of the signature moments.

The interaction between the men’s quartet was especially detailed and filled with resourceful playfulness. The lovers’ flirtations, first between Rodolfo and Mimi, and then Musetta and Marcello, were sexily inevitable. The character relationships had specificity, movement was well motivated, and the crowd scenes were tightly controlled as the groupings fluidly morphed to accommodate the script’s demands. Both Lisa Hasson’s Apprentice chorus and Barbara Sletto’s Children’s Chorus did themselves proud.

Conductor Michael Christie led an assured, stylistically sound, and dramatically pliable reading, inspiring the exceptional DMMO orchestra to respond with an ensemble effort that ranged in effects from luxuriant, to lush, to comtemplative, to crackling. Maestro Christie excelled at accommodating his singers, partnering them with great finesse. And what a set of soloists they were!

Tenor Joshua Guerrero’s opulent spinto instrument was all you could wish for, as he conquered the role of Rodolfo. Mr. Guerrero had an impetuous, boyish appeal that illuminated the opening acts, as he sang with fresh-voiced abandon and pranced about with ebullient youthfulness. By Act III, the performer ably weighted his delivery with appropriate pathos and despair. His straightforward Italianate style was tremendously appealing, even down to the occasional sobbing catch in a phrase or three.

He was beautifully paired with his Mimi, the radiant soprano Julie Adams. Her rich, luminous tone, plangent delivery, total command in all ranges, and ability to effortlessly ride the most impassioned orchestral passages were thrilling to hear. Ms. Adams is a sincere and unaffected actress, and the heartrending tale of love lost was communicated with unerring commitment and lustrous singing.

Thomas Glass proved an exceptional Marcello, his buzzy, beefy baritone ringing out with character and conviction. His bromance chemistry with Rodolfo yielded many engaging moments and their synergy in the Act III trio, and especially in their party piece duet that begins Act IV was musically ravishing and dramatically touching.

Mané Galoyan discovered her own spunky take on Musetta, one that was longer on sensuality than it was on sass. This not only paid good dividends in Act II’s tease of Marcello, but also laid the groundwork for the more serious side she demonstrates by opera’s end. Ms. Galoyan is a highly proficient soprano, attractive and secure, and she knows just how to utilize it to maximum effect. I am not sure I have ever heard the penultimate note of Quando m’en vo held to such maximum length and effect.

Bewhiskered, brawny Timothy J. Bruno made for an endearing Colline, his orotund bass rolling out with ease and obvious enjoyment. When it came time for him to tug our hearts, Mr. Bruno did not disappoint and obliged with a moving Coat Aria. Tall, slender and nimble, baritone Brian Vu found more in Schaunard’s arsenal than we often encounter. His sizable, incisive baritone contributed a gleaming presence, and his easy stage presence had enormous appeal.

It is a joy to encounter a production that is peopled by actors that actually look like young, struggling artists. I have encountered many stagings in which some, even all of the main quartet of men sported waistline numbers that exceeded even their considerable ages. Kudos to DMMO for so carefully casting such accomplished young stars that also were able to bring the familiar tale to such believable fruition.

Rounding out the cast, bass Matthew Lau found admirable variety in doubling the roles of Benoit and Alcindoro. His solidly sung portrayals found playfulness and camaraderie as the former, and long-suffering frustration as the latter.

By the time this laudable assemblage of talent brought us to the end of their journey, with Rodolfo screaming his anguish at Mimi’s deathbed, the other bohemians grieving each in their own way, the radiant orchestra melting into the tragic final chords, if you didn’t have a lump in your throat and a tear in your eye, well, you were at the wrong address.

La bohème. Des Moines Metro Opera. An “old-fashioned smash,” indeed.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Rodolfo: Joshua Guerrero; Marcello: Thomas Glass; Colline: Timothy J. Bruno; Schaunard: Brian Vu; Benoit/Alcindoro: Matthew Lau; Mimi: Julie Adams; Parpignol: Andrew Turner; Musetta: Mané Galoyan; Drum Major: Anthony Benz; Customs Officer: Andrew Gilstrap; Sergeant: Aaron Keeney; Conductor: Michael Christie; Director: Octavio Cardenas; Set Design: Robert Little; Lighting Design: Sarah Riffle; Make-Up/Hair Design: Brittany Crinson; Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson; Children’s Chorus Master: Barbara Sletto

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DSC_4076.png image_description=Scene from La bohème [Photo by Duane Tinkey courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera] product=yes product_title=Sublime Bohemians Captivate Indianola product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id=Above: Scene from La bohèmePhotos by Duane Tinkey courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera

July 27, 2019

Des Moines: Best of All Possible Candide’s?

Director Michael Shell had enough brilliant ideas for three productions, which at several gilded lily moments may have been one production too many. However, his task was not an easy one. Since I have addressed this before, I am going to quote myself:

Candide began life as a notorious 1956 Broadway flop, most notable for a Columbia cast recording, which showcased Bernstein’s eclectic score. After the show languished for some years, Harold Prince devised a 1 hour and 45-minute version with a new libretto by Hugh Wheeler, which was such a success at Brooklyn Academy of Music in 1973 that it moved Broadway for a hit two-year run in 1974. It was this lean and mean, interactive production that won me over, and I saw it four times. At last this meritorious score was married to a sassy, witty book and its previous problematic lack of Voltairean elan and coherent focus were fixed! Mais, attendez-vous. . .

Energetic Glimmerglass Candide

Now that it was a hit, opera houses expressed interest in a proscenium version in two acts. Prince (and others, including Bernstein) agreed to continue to tinker with it and began adding back in characters and songs that were extraneous. The temptation seems to have been great to re-order and darken the plot, resurrect good numbers that are nevertheless unnecessary, and worst, give enjoyable characters a weak second or third number that deserved to remain in Lenny’s trunk.

From the original recording, “Quiet” and “What’s the Use?” made a return to no real dramatic advantage other than being interesting tunes aurally. “The Venice Gavotte” had been re-purposed in 1974 as a delightful expository quartet (with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, no less). That quartet still opens the show, but now we have an action-stopping Gavotte in Act II as well, reprising that material and then some, adding length if not interest. In short, Bernstein’s Candide seems to have more performance versions than Tales of Hoffmann.

Back to the present review: In a survey, Candide was voted as the opera DMMO’s discerning audience most wanted to see and professional leasing arrangements now require that they use the official, composer-sanctioned Scottish Opera version. Des Moines’ entertaining staging stays true to the integrity of this “official” compilation, all the while seeking inventive means of enlivening it.

First off, Mr. Shell et al have quite correctly imagined this as a musical comedy. The satirical humor almost never fails to land thanks to craftily designed, richly nuanced interaction. I have never seen an audience more delighted by “You Were Dead, You Know,” including Mr. Prince’s legendary Broadway resurrection. Never. Shell knows his way around a comedy and a captivated auditorium was utterly engaged by his (often) ribald revelry.

I loved the whole improvisational feel of the evening. The choice of having Voltaire as a stand alone character, “writing” the show we were seeing as it transpired, was a master stroke. The formidably charming actor Wynn Harmon made much of his role as the motivator, scripter, and MC of the story. He steers the proceedings with aplomb and serves as the glue to hold this whole concept together and keep it careening merrily forward.

The sturdy baritone of Kyle Albertson not only enlivens Dr. Pangloss but serves up the cameo star turn of the pessimist Martin with panache. The latter character being wholly extraneous, Mr. Alberston nevertheless pins our ears back with his bombastic, cynical solo. (In a sad footnote, Kyle replaced the late Robert Orth who was to have performed these roles, and to whom the production was dedicated.)

Tenor Jonathan Johnson is arguably the finest Candide of my experience. Not only is he boyishly appealing, he sings like a god. I have never heard the added aria “Nothing More Than This” more heart wrenchingly presented, all limpid tonal production and exquisitely poised sentiment. Deanna Breiwick is similarly stellar as Cunegonde. Eerily recalling Kristin Chenoweth (who famously played the role with the NY Philharmonic), Ms. Breiwick has it all: a plangent, flexible soprano of uncommon accomplishment; a savvy stage presence; and a meticulous musical technique that informs her well-rounded, polished portrayal. She literally stopped the show with her madcap, electrifying rendition of “Glitter and Be Gay.”

Emmett O’Hanlon’s self-important take on the egotistical Maximilian was well-served by a warm, responsive baritone and a lanky, handsome physique. Although he executed a slight Westphalian/German accent with skill, it was curious that no other Westphalian characters were so inclined and spoke in straight forward English. That decision was a curious distraction.

Eliza Bonet was a memorable Paquette, not an easy accomplishment since the character disappears for long stretches at a time. Ms. Bonet made the most of her every appearance embodying an infectious good humor, all the while wielding a vibrant, sizeable mezzo.

The venerable Jill Grove delivered the required star turn as a castanet-wielding Old Lady, singing the part with a lush, potent mezzo that made her traversal of “I Am Easily Assimilated” a real highlight. The production has curiously given her two "false start" star entrances. She comes on twice, each time “too early” in the progress of the story, castanets ablaze and is twice sent back off stage by Voltaire. This was a game attempt for a laugh, but did not quite land.

Curiously, in the Scottish Opera version of what was the Old Lady’s big monologue, which IS her star turn, the lines have been distributed between her and other characters, some of them choristers. The staging did its best with this revision, but I wish that the redoubtable Ms. Groves had been able to be given command of the whole original speech and left to manage its build and payoff.

Corey Bix was a larger than life Governor, threatening the paint on the walls with his commanding tenor. If he encountered a fuzzy patch or two, Mr. Bix knows how to sell a song and his artistic aplomb dominated his scene. Corey Trahan’s Cacambo was delectably witty. Mr. Trahan is a master of dialects (he uses several, each funnier than the last) and his comic timing is second to none. He enlivened his every scene and was yet another treasurable asset to this fast-paced evening’s entertainment. There are cameo roles too numerous to mention, all impersonated with ingenious individuality and securely sung by topflight talent.

Thanks to the unique configuration of the Blank Performing Arts Center, director Shell’s staging has come the closest of any I have seen to suggest the atmosphere of the 1974 revival. Long before “immersive” theatre became today’s cliché for audience interaction and participation, Hal Prince “in the day” cooked up a Candide that had the audience everywhere in a circus-like configuration, and that saw actors passing conspicuously through patron seating, gadding about ramps that encircled whole sections, popping up in the audience, and tirelessly unfolding a fable that was often in dizzying motion. That was the great strength of that revival, and the same successful dynamic, albeit contained to stage and thrust, currently informs DMMO’s rambunctious presentation that spills and tumbles over every square inch of playing space.

Certainly Steven C. Kemp’s wildly original set design provided (primary) colorful additions with almost every change of scene. From the opening set of four massive, illuminated white bookcases, pieces came and went with such frequency (there are a LOT of different scenes) that I failed to notice at first that bits and bobs of most pieces remained behind, resulting over time in a rather cluttered collection of all the absurd locales and plot turns. The loudly applauded goof of having a flock of sheep “fall off” a gilded mountain in El Dorado, only to land in a clanking, cluttered, ignominious heap was alone the price of admission. Yahadda be there.

Nate Wheatley contributed another accomplished lighting design, mostly keeping the whole affair colorfully atmospheric, but for the several introspective scenes and arias, he concocted looks of appealing poignancy. Linda Pisano provided a tremendous costume design, notable for its unbelievable variety, its riotous colors, and its sheer number. The big production numbers were visually eye-catching, stage filling, and well-coordinated, thanks also to Todd Rhoades crackerjack, well-rehearsed choreography.

Having conducted a wrenching Wozzeck the night before, David Neely seemed to find a perfect way to cleanse the pallet as he led an effervescent reading of Candide. From the downbeat of the thrice-familiar overture to the stirring choral finish, Maestro Neely steered his accomplished forces with infectious relish.

Given the limitations of the edition that must now be used, might this have been the best of all possible Candide’s? The superb talent on display, the many happy solutions that mitigated structural challenges, the imagination and commitment to making Candide still work in the 21st Century, all lead me to say “yes.” I do know this: As the principals and Lisa Hasson’s thrilling Apprentice chorus sang the full-throated a capella section of “Make Our Garden Grow,” enveloping us in one of Bernstein’s most unbearably beautiful passages, there was nowhere else I wanted to be. It was the best of all possible moments.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Voltaire: Wynn Harmon; Dr. Pangloss/Martin: Kyle Albertson; Candide: Jonathan Johnson; Paquette: Eliza Bonet; Baron/Grand Inquisitor: Jesse Stock; Baroness: Emily Triebold; Cunegonde: Deanna Breiwick; Maximilian: Emmett O’Hanlon; Old Lady: Jill Grove; The Governor: Corey Bix; Cacambo: Corey Trahan; Croupier: Robert Gerold; Prince Ragotski: Alexander McKissick; Captain: Evan Hammond; Conductor: David Neely; Director: Michael Shell; Set Design: Steven C. Kemp; Lighting Design: Nate Wheatley; Costume Design: Linda Pisano; Make-Up/Hair Design: Brittany Crinson; Choreography: Todd Rhoades; Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DSC_0103.png image_description=Scene from Candide [Photo by Duane Tinkey courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera] product=yes product_title=Des Moines: Best of All Possible Candide’s? product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id=Above: Scene from CandidePhotos by Duane Tinkey courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera

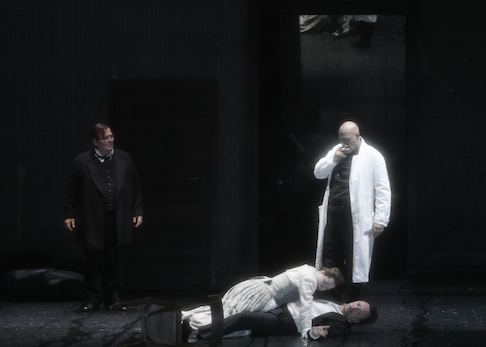

Profoundly Bone-chilling Wozzeck

I am happy to report that although I have only ever seen good productions worldwide of this challenging Alban Berg opus, I had to come to Indianola, Iowa to see the very best. This mesmerizing performance would be at home on any world stage, and the reasons are many.

In the title role, triumphantly singing torturously difficult music, Michael Mayes is nigh unto perfection. He is possessed of a ringing, freely produced baritone of uncommon power and beauty and he knows exactly how to deploy it in service of this demanding score. The rangy leaps, the emotional shifts, the sudden outbursts of Sprechstimme, the complex harmonies, none of this holds any terror for a singing actor at the top of his game.

Mr. Mayes is as fine an actor as you will find on any stage, and his deeply personalized account of the character’s inexorable descent as he unraveled into violence was riveting. He winced, he gasped, he wept, he shuddered, he mourned, he snapped, he writhed, he trembled, and he prowled the premises, all the while creating a nuanced, unsettling portrait of an unstable human being decidedly ill-treated by his fellow man. Mayes infused the character with so much pitiable humanity, that in the end he was not so much killer, as killed by those in his sphere. His was a stunning achievement.

Every bit his equal, Sara Gartland was a revelatory Marie. Her gleaming soprano brought much lyric beauty to the role, and her limpid vocalizing evoked significant sympathy for her joyless existence. Ms. Gartland also found sufficient full-bodied brass in her tone for the scripted shrewish angry outbursts, as well as suitably lustful overtones for her hedonistic inclinations.

Her dramatic depiction of the conflicted character skillfully vacillated between her understandably dwindling attraction to Wozzeck, her bastard child’s father, and her uncontained lust for money and emotional support. Since her only asset in life is her alluring sensuality (and Sara is a beautiful woman indeed) she must use it judiciously to get what she needs to survive. Hers was an impeccably sung, richly complex portrayal.

Cory Bix put his stentorian tenor to good use as an abusive, bloated Captain. When his assured eruptions weren’t laced with venom, Mr. Bix skillfully found a way to make them drip with irony. His sturdy instrument had tightly focused presence in all registers, but the passaggio encountered some wooliness in early measures that lessened as the show went on.

Zachary James was molten malevolence as the malpracticing Doctor. Mr. James colored his sizable bass-baritone with menacing intent and his looming physical presence was enhanced by a hunched back and disfiguring facial prosthetics. (Brittany Crinson’s make-up and hair designs were terrific throughout.)

Robert Watson could hardly have been better as the preening, savage Drum Major. Mr. Watson is possessed of a laser-focused tenor of astonishing amplitude and color that was a fortuitous fit for the testosterone-driven, assault prone ne’er-do-well. Gregory Warren was such a gleaming, sure voiced Andres, that I wished Berg had given him more to sing. His physicality and fluid vocalizing ably conveyed the essential kindness of one the opera’s only sympathetic characters.

Margret is given few chances to shine, but Zoie Reams nonetheless made a fine impression, her pliant mezzo impressive for its richness and warmth. Timothy Bruno’s rolling bass and burly presence made a fine impression as the First Apprentice, and Brian Vu complemented him nicely as the Second Apprentice, sporting a meaty baritone and a lanky, lean appearance.

As the Fool, “baritenor” Corey Trahan’s diminutive stature and focused performance was eerily haunting, and nonchalantly unnerving. Lisa Hasson’s chorus of apprentice artists performed their difficult assignments flawlessly. As Marie’s Child, youngster Benjamin Bjorklund was heart-tuggingly engaging.

All of this superlative singing and powerful emoting was exquisitely buoyed by the miraculous sounds emanating from the pit. David Neely, always admirable, has simply never conducted better as he elicited musically vibrant, dramatically potent, and vividly colorful performances from his amassed forces, a rendition of a caliber you seldom hear at even the most celebrated world festivals.

From the lush banks of strings to the staccato punctuations by the brass to the commentary by the winds to the explosive effects by the percussion, this was a luxuriant reading that restlessly unfolded with an arc of spontaneity and inevitability. Bravo, Maestro!

In equal partnership, director Kristine McIntyre has once again brought soul-stirring inspiration and clarity of purpose to a very difficult piece. I think I ran out of superlatives to describe her artistic accomplishments two reviews ago, but suffice it to say this nonpareil version of Wozzeck has not only met her own very high standards, but has raised her own bar one notch higher.

The design team has abetted Ms. McIntyre with a jittery, spectacularly skewed milieu that visually matched the instability of the protagonist’s mind. Vita Tzykun’s spot on expressionistic costumes were exceeded in accomplishment only by her tremendously complicated set design.

The proscenium is covered by numerous flying pieces, most at cockeyed angles that fly in and out in countless combinations to reveal different locations, various characters, and finally the entire lakeside setting where Wozzeck kills Marie and inadvertently himself. Under the expert direction of production stage manager Brian August, the run crew outdid themselves operating all of this complicated movement with the utmost precision.

The action inevitably spills on the forestage of the thrust, making full utilization of that area, to include the sizable trapdoor space that became a trench for some physical action that was well devised by fight coordinator Gina Cerimele-Mechley. Lisa Thurrell contributed some effective choreography that included unhinged twitching and posing by the chorus at the climax of the tavern scene. That moment culminated with the men stripping to their long underwear, and the ladies carrying away the costume pieces as the men seamlessly became the soldiers who sunk to the floor to “sleep” in their barracks.

That transition was one magic moment of many thanks to Kate Ashton’s marvel of a lighting design. Ms. Ashton created one moody, isolated look after another, often punctuated by random bursts of light on the proscenium flats that reflected the unraveling hallucinations that misfired in Wozzeck’s troubled mind.

But it was Ms. McIntyre that successfully pulled this unified vision together and invested it with her customary passion and intelligence. Never have I been so engrossed by the journey all of these personages are making. Part of that is owing to the beauty of the proximity to the stage in the Blank Performing Arts Center. But it was the masterful director who ensured to a person, the characters on the stage were committed, honest, and compellingly believable.

Lustrous musical effects, meaningful character interaction, world class singing and playing, heart-stopping intimacy, a masterpiece vividly brought most impactfully to life – where else but Des Moines Metro Opera?

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Wozzeck: Michael Mayes; Captain: Cory Bix; Andres: Gregory Warren; Marie: Sara Gartland; Drum Major: Robert Watson; Doctor: Zachary James; Margret: Zoie Reams; The Fool: Corey Trahan; First Apprentice: Timothy Bruno; Second Apprentice: Brian Vu; Marie’s Child: Benjamin Bjorklund; Conductor: David Neely; Director: Kristine McIntyre; Set and Costume Design: Vita Tzykun; Lighting Design: Kate Ashton; Make-Up/Hair Design: Brittany Crinson; Choreography: Lisa Thurrell; Fight Director: Gina Cerimele-Mechley; Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DSC_0291%20update.png image_description=Scene from Wozzeck [Photo by Duane Tinkey courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera] product=yes product_title=Profoundly Bone-chilling Wozzeck in Iowa product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id=Above: Scene from WozzeckPhotos by Duane Tinkey courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera

July 25, 2019

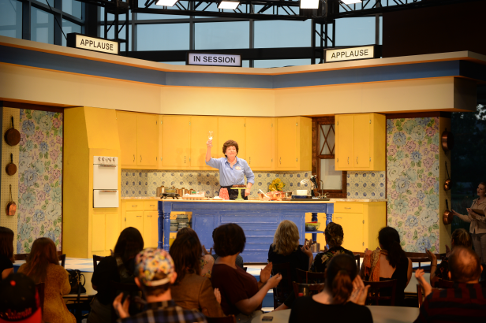

Des Moines Cooks Up a Novel Treat

Patrons lucky enough to score a ticket to the SRO soiree were provided an extensive, multi-course dinner with suitable libations, and the evening was first punctuated by snappy song performances from four appealing young Apprentice Artists.

As the crowd was tippling some bubbly, Catherine Goode’s poised soprano, Joyner Horn’s rich mezzo, Quinn Bernegger’s polished tenor, and Robert Gerold’s accomplished baritone warmed up the proceedings with an opening set of such novelty songs as I Can Cook, Too, Frim Fram Sauce, Tea for Two, and Peel Me A Grape. As the audience tucked into their main course, the quartet returned to position themselves amid the audience accessorized with cute costume pieces and props (including a rubber chicken), to divvy up the duties of Bernstein’s quartet of French recipes set to music, La bonne cuisine.

But artistically, the evening belonged to local favorite, mezzo-soprano Joyce Castle who was utterly engaging in her winning star turn as Julia Child in Lee Hoiby’s twenty-minute opera, Bon Appetit. To enthuse that Ms. Castle is a National Treasure is simply too weak praise for her perfectly calibrated, masterfully voiced “tour de farce.” Although she has a potent, full-bodied instrument, on this occasion, she modulated her delivery to convey Julia’s tongue in cheek personality, reveling in all its comic quirkiness.

And if there is another opera star that has Castle’s unique brand of charisma, musicality, and unerring comic timing I don’t know who it is. Together with director Nathan Troup, this singing actress mined a wealth of sight gags, takes, deadpans, asides, eye rolls, and comic business that kept the audience tittering and applauding in giddy delight the entire length of the piece.

Without slavishly impersonating the famous chef, she managed to push all the familiar buttons with an affectionate portrait that never descended into caricature. To name but one memorable moment, the slyly nonchalant appearance of Ms. Child’s signature glass of white wine was so comically shameless that the audience surrendered whatever was left of their composure and howled with glee. This lady knows how to keep and captivate a crowd.

The libretto by Mark Shulgasser is based on an actual airing of The French Chef in which a chocolate cake is baked. The sole suspense is whether the somewhat scattered cook will get the recipe together and the cake produced. Any guesses as to the outcome?

After the sustained, resounding cheers that were rained on Joyce finally diminished, and attendees resumed their seats from bestowing a well-deserved standing ovation, all were served a slice of Bon Appetit’s signature chocolate cake as their dessert course.

While the technical elements were of necessity simple, they were nonetheless all that was needed to present a polished effect. Adam Crinston’s TV Kitchen set was handsome, bright, and well appointed; Nate Wheatley lit it simply and evenly; Heather Lesieur’s costume conveyed just the right Child-like look; and Sarah Norton’s make-up and wig completed Ms. Castle’s transformation.

The skillful pianist Elden Little played with power, playfulness, and panache all evening long. For diners and opera-goers alike, Bon Appetit was a wholly delectable “happening,” a feast for eyes, ears and tummy alike.

One final note about the remarkable, enduring career of Joyce Castle: After a very long and distinguished run as one of Operadom’s most beloved, prolific, and successful performers, the mezzo continues to gift us with new role assumptions like Julia Child. She will next undertake her first Countess in next summer’s The Queen of Spades. Long may she rave! Mark calendars now!

James Sohre

Bon Appetit by Lee Hoiby

La bonne cuisine by Leonard Bernstein

Songs by assorted composers

Julia Child: Joyce Castle; Featured Performers: Quinn Bernegger, Robert Gerold, Catherine Goode, Joyner Horn; Pianist: Elden Little; Director: Nathan Troup; Set Design: Adam Crinson; Lighting Design: Nate Wheatley; Costume Design: Heather Lesieur; Make-Up/Hair Design: Sarah Norton

image=http://www.operatoday.com/DSC_0679.png image_description=Scene from Bon Appetit [Photo by Duane Tinkey courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera] product=yes product_title=Des Moines Cooks Up a Novel Treat product_by=By James Sohre product_id=Above: Scene from Bon AppetitPhotos by Duane Tinkey courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera

July 24, 2019

The VOCES8 Foundation is launched at St Anne & St Agnes

At a concert by VOCES8 and Apollo5, is the answer. Diversity, together with vocal discipline and strong musical direction were the touchstones of the performance I attended at the VOCES8 Centre at St Anne & St Agnes in the City of London earlier this month, where long-standing supporters of the two vocal ensembles gathered with new audience members to mark the renaming of the VCM Foundation as the VOCES8 Foundation.

VOCES8 was founded by brothers Paul and Barnaby Smith in 2005, and the following year the music charity VCM Foundation was established to develop the ensemble’s music education and outreach programmes which today reach up to 40,000 people a year.

Initiatives include an annual programme of workshops and masterclasses at the Foundation’s home at the VOCES8 Centre; the VOCES8 Scholars programme, set up in 2015, which offers eight choral scholarships to young singers providing valuable experience and contacts as they commence their professional careers; and the unique teaching tool The VOCES8 Method, developed by Paul Smith, which adopts music to enhance development in numeracy, literacy and linguistics and is available in four languages.

VOCES8 don’t rest on their laurels either. 2017 saw the launch of the US Scholars Programme. The ensemble is the Associate Ensemble for Cambridge University and delivers a Masters programme in choral studies at the university. They are also official Ambassadors for Edition Peters, who published the VOCES8 method and this season the ensemble became Ambassador for the Tido App, an inspirational resource and learning tool created by Edition Peters.

This summer VOCES8 are the resident ensemble at the Milton Abbey International Music Festival, where they will deliver the VOCES8 Summer School in conjunction with the Festival. Now these activities, along with the work of the sister group Apollo5 and VOCES8 Records, will be brought together under a single unifying banner, the VOCES8 Foundation.

When I heard VOCES8 perform alongside Rachel Podger at King’s Place in March 2018 I remarked they ‘were notable for their unblemished blending, pure tone, true intonation and shapely phrasing - and, notably, their confident execution under the unobtrusive direction of countertenor Barnaby Smith’ and that they were equally accomplished in stylistically diverse idioms and genres. So, I was looking forward to this celebration of the 2018-19 season at the VOCES8 Centre, with performances of some of the works that have been highlights of the past year.

First, though, Apollo5 made the mystical strains of Pérotin’s Beata Viscera resonate transcendently across and around the Church of St Anne & St Agnes. It was wonderful to hear the blended sound unfold in Byrd’s own setting of the Communion motet for the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, so that the steady uniformity of Byrd’s setting was animated with the spirit of belief, before an expansive and confident Alleluia. Apollo5 also performed ‘Wishes’ by Fraser Wilson, a mellifluous composition in which the even-paced wandering of folk-like melody was supported by a smooth cushion occasionally made piquant by text-illuminating harmonic twists.

‘ Wishes’ is included on Apollo5’s recently released CD, O Radiant Dawn , along with Wilson’s arrangements of traditional songs, ‘Scarborough Fair’ and ‘The Skye Boat Song’. There’s also a folk arrangement by another contemporary choral conductor, Alexander Levine, of a traditional Russian song, ‘Oh, You Wide Steppe’ which was also performed at St Anne & St Agnes. The sustained tones of the opening are haunting, but the rich blossoming of subsequent verses brings a frisson of passion for the homeland and the free flowing River Volga. It’s a striking conclusion to the disc.

O Radiant Dawn comprises characteristically eclectic repertoire: from Thomas Morley’s ‘I Love, Alas, I Love Thee’ to Ralph Vaughan Williams ‘The Call’ (arr. Harry D Bennett), from Claudio Monteverdi’s ‘Sfogava con le stelle’ to the album’s eponymous motet by James MacMillan. The rhythmic precision and the concordance of tuning and phrasing of the four-part homophony in the latter is superb, and the delicate, rising and falling thirds for soprano and alto in the central episode are no less carefully placed. The performance conveys both the joy of the new day and a hint of man’s vulnerability before the glory of God.

The Elizabethan madrigals seem to my ear more successful than the polyphony of Byrd; in Orlando Gibbons’s ‘The Silver Swan’ - taken here at quite a slow, reflective pace which makes those dark, desirous chromaticisms all the more deliciously telling - the ensemble seem to respond instinctively to the text and craft a sure overall structure. The same is true of Monteverdi’s madrigal (from the Fourth Book) in which the declamatory style is imbued with energy which pushes towards the musical conceits delineating the vivid images of Rinuccini’s text.

The CD liner booklet includes texts and translations, although the singers from the group (Penelope Appleyard and Clare Stewart (sopranos), Joshua Cooter and Oli Martin-Smith (tenors) and Greg Link (bass) who perform solos within particular items are not identified, and nor are there explanatory notes. The sound is resonant and rich. This is an hour’s worth of music of moving luminosity and lyricism: music which, in the ensemble’s own words, reaches for ‘a glimpse of the sublime’.

At the Church of St Anne and St Agnes, Apollo5’s atmospheric performance was followed by a similarly diverse series of items by VOCES8. The rendition of Sibelius’s hymnic ode ‘Be still my soul’ was tremendously impassioned and rich - were there really only eight singers? - while Dove’s setting of George Herbert’s ‘Vertue’ captured the gradual darkening of the poem’s sentiments, as the death that shadows all natural things grows ever more present, only evaded by the virtuous soul which will be made eternal through union with God. The swelling divisi phrases of ‘Let My Love Be Heard’, a setting of a poem by Alfred Noyes by American composer Jake Runestad, offered both a sense of catharsis following grief and softer consolation, while similar certainty and comfort was offered by polyphonic expressions of faith by Thomas Luis de Victoria and Orlando di Lasso.

VOCES8’s ability to switch from one idiom to another in a blink of the eye, and perform anything from motets to the melodies of Broadway which equal accomplishment and stylishness, was demonstrated by their soulful rendition of Joshua Pacey’s arrangement of ‘Danny Boy’ and the cool clarity of Antonio Carlos Jobim’s ‘One Note Samba’ which brought proceedings to a close.

The evening had opened with three compositions by Paul Smith, performed by the VOCES8 Scholars, Apollo5, soloist soprano Clare Stewart and viola player Neil Valentine. These works are included on Smith’s forthcoming debut album, Reflections, which features 2,500 voices from across the globe, from age 8 to 80, personally recorded by Paul on his travels over Asia, Europe, Africa and America during the last decade: ‘the disc moves from plainchant to lullabies, early opera to contemporary choral, inviting the listener on a journey of introspective reflection’.

‘Chant’ began with a searching melody meandering about a sustained tone, the latter expanding slowly into a sound wave punctuated first by Valentine’s quiet but pressing pizzicati (more audible on the recording than live in the church) and then by delicate piano reflections which urge the viola to take flight in a poignant melody. Think Enya meets Keith Jarrett. Very chilled. Smith’s Nunc Dimittis, in contrast, is more Tavener-like in its pulsing chords and registral contrasts, and in its striving towards finely grained, warm, euphonious resolution - with a tinge of tension lingering in the after-silence.

The first performance of Reflections took place at an IMAX cinema in California, at a special event which raised $100,000 for a local music charity. The disc is released by VOCES8 Records on 2nd August 2019.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/VOCES8%20Gresham%20Centre.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The VOCES8 Foundation is launched at the Gresham Centre. product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: VOCES8A stirring War and Peace by WNO at Covent Garden

What had started life as a fictional narrative that was to dramatise fifty years of Russian history (at a time of national crisis following Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War) and to depict the same social milieu in the epochal years of 1812, 1825 and 1856, quickly outgrew the conventional form of the novel. In the end, content and purpose dictated structure, and the resulting expansive narrative of the years 1805-12 lacks the tidiness, balance and conclusiveness that the novel form demanded in the late-nineteenth century. It is also, in the words of the editors of a study of War and Peace published in 2012, the year of the two hundredth anniversary of Napoleon’s fateful invasion of Russia and the Battle of Borodino, ‘a founding epic for modern Russia and a meditation on war and history … one of the most read and most important novels ever written’. [1]

However, sprawling 19th-century novels - particularly those so labyrinthian, lacking in cohesiveness and clear resolution, and which foreground philosophical and political debates sometimes at the expense of focused characterisation - do not, in general, good opera libretti make. When Sergei Prokofiev and and his co-writer, and second wife, Mira Mendelson decided to adapt War and Peace for the Soviet stage during the 1940s, the composer was forced to grapple not just with the unconventional, uncontainable form of Tolstoy’s text, but also with the conventions of his own art form - was this to be a romance in the Tchaikovskian model or an epic history in the manner of Musorgsky? - and with the ideological demands of Stalinist propaganda. Prokofiev decided to keep opposing strands separate. What we have is a first 90-minute Act, Peace, followed by a longer second Act, War. In the first, the landowning classes - lovers of all things French - engage in social sorties against the backdrop of war; in the second, we have a violent, catastrophic clash of nations culminating in Napoleon’s 1812 retreat from Moscow, in which the aristocrats of part one are reduced to incidents in an epic historical narrative.

If adapting the novel for the operatic stage was a daunting task, then staging Prokofiev’s four-hour opera must be an even more formidable challenge: even if one’s budget were infinite, there are still the inherent contradictions within the drama to reconcile - between romance and realism, between social milieu and Soviet militarism, between individual relationships and the nation’s collective love for the Motherland. And, there’s the small problem of the lack of a definitive score. Following the completion of a vocal score in 1942, Prokofiev subsequently made a series of revisions during the years before his death in 1953 in an ultimately unfulfilled effort to have his work brought the stage. In mounting this production of War and Peace, first seen in Cardiff in September 2018 and given two performances at the Royal Opera House, director of WNO Sir David Pountney decided to make use of Prokofiev’s first score, which was revived by Prokofiev scholar Rita McAllister for a 2010 collaboration between Scottish Opera and the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama, but also include some of Prokofiev’s later additions and amendments. It’s sung in English and the projection of the persuasive translation is uniformly excellent.

WNO Chorus. Photo credit: Clive Barda.Designer Robert Innes Hopkins brings the stage-embracing ‘bowl’ of 2016’s staging of Iain Bell’s In Parenthesis back into service. Around its top rim, a narrow platform permits onlookers a view of the action below. Behind, David Haneke’s video projections - which include extracts from Sergei Bondarchuk’s 1966 film of Tolstoy’s novel - offer a visual reconstruction of Russian history. The design has two-fold benefits in that it both allows individuals to emerge from the broader panorama of history and also creates a distancing effect - one furthered by the period costumes hanging from clothes-rails and wall-hooks either side of the stage - which suggest that we, alongside the Russian people, are peering back into the past. A further ‘layer’ is added by the presence of Tolstoy, seated at his desk at the start of the opera, his Cyrillic script projected on the backdrop above. As the characters formed by the writer’s pen - princes and peasants, the military and mothers clutching pitchforks - swarm around him, we get a strong sense of both a literary narrative and history itself in the making.

Lauren Michelle (Natasha) and Jonathan McGovern (Andrei). Photo credit: Clive Barda.The opening of the opera proper takes one unawares though: the multitudinous personnel of the WNO Chorus mingle and meander about the stage as the orchestra tune up, and then suddenly we are bombarded with a blast of sound that might have come direct from the barricades. This is the voice of the Russian people, and they sing with all their hearts, here and in a series of flag-waving, social realist grand choruses, of their love for Mother Russia. The Chorus make a terrific thunder, and they are matched for energy and colour by the WNO Orchestra under Tomáš Hanus. Hanus relishes the moments of instrumental lift-off, when the heroic whoosh of brass and horns is complemented by the sparkling sweep of the harp - when outsize chandeliers descend low for the ball, or when the backdrop is engulfed in an inferno. But, he is painstaking also during moments of intimacy and (though they are fewer) psychological revelation, where the textures are clearly defined as inky bassoon, black bass clarinet and tense oboe delineate the merging of personal and political.

Pountney and Innes Hopkins at times lower a drop to push the action to the forestage, as when Andrei espies Natasha at her bedroom window or for the debate and deliberation in the Council of War bunker. Hanus also engenders a strong sense of movement in the dance episodes which punctuate the score, even as they rather stall the action - we’re reminded of Prokofiev the ballet composer. Sometimes Pountney overdoes the patriotism and propaganda, and there’s an unfortunate ‘comic’ military scene towards the close which had the Russian couple seated next to me in the stalls guffawing - though perhaps that was the intent.

Pountney’s management of the ‘whole’ is ambitious and accomplished. But, while the grand choruses make their impact, I’d have liked more detailed direction of the individual characters who are often pushed into the spotlight and then left to their own devices. That’s not to detract, though, from the marvellous singing on display from principals and chorus alike, many of whom take on three or four different roles and who display real commitment and stamina.

Lauren Michelle (Natasha) and Mark Le Brocq (Pierre). Photo credit: Clive Barda.Pierre, whose love for Natasha remains unrequited, comes increasingly to the fore as the drama progresses and Mark Le Brocq offered a superb performance, communicating both strength and vulnerability, phrasing with tenderness but delivering with conviction. Jonathan McGovern used his strong, youthful baritone well, and developed a nice rapport with Lauren Michelle’s Natasha; the latter impressed as Jessica in Keith Warner’s staging of The Merchant of Venice in this house in 2017, and here the American soprano sang with lovely colour and warmth. The scene in which Natasha, now a military nurse, is reunited with the dying Andrei was the episode which initially inspired Prokofiev to attempt a setting of Tolstoy’s novel. Pountney eschews a battlefield demise and returns Andrei to the window wherein he first encountered Natasha, to which she returns in his dying moments. On the plus side, our bird’s-eye perspective is consistent with the distancing of the whole and places the beloveds at a historic remove. On the downside it denies their duet its centrality in the dramatic arc.

Adrian Dwyer sang half-a-dozen cameo roles and was excellent as the disreputable Anatole who steals Natasha’s heart and condemns her to social humiliation. James Platt reverberated richly as Count Rostov (and valiantly takes four other roles). David Stout truly excelled, in terms of both characterisation and musicianship, as Dolokhov, Denisov, Raevsky and as a steel-backed Napoleon, his voice bursting with pride and defiance in the latter incarnation, but always appealing. Jurgita Adamonytė was a vivacious Helene and Leah-Marian Jones (as Princess Marie Akrossimova) made a similarly strong and colourful contribution. Pountney rather sends up Field Marshal Kutuzov - presumably portraying him as a stand-in for Stalin - but Simon Bailey delivered a tremendously impassioned declaration during the war council.

The editors of the aforementioned Tolstoy On War remark that the premise of their collection of essays is that ‘the issues in Tolstoy’s novel are too complex to be comprehended satisfactorily within a single academic discipline. No one discipline owns war.’ One might perhaps suggest that the complexities of the novel are too vast and complex to be made cohesive within and communicated satisfactorily by any single art form? But, valiant ambition comes in all shapes and sizes, and we should be very grateful to Welsh National Opera for showing us the heroism of Prokofiev’s endeavour in such splendid fashion.

Claire Seymour

Prince Andrei Bolkonsky - Jonathan McGovern, Natasha Rostova - Lauren Michelle, Count Pierre Bezukhov - Mark Le Brocq, Princess Marya Bolkonskaya/Princess Marya/Aide de Camp of Murat/Mavra Kuzminichna - Leah-Marian Jones, Hélène Bezukhova/Aide de Camp de Prince Eugene/Dunyasha - Jurgita Adamonytė, Anatole Kuragin/First General/Kutuzov’s Aide de Camp & Adjutant & First Staff Officer/Aide de Camp of General Comans/Bonnet/Barclay - Adrian Dwyer, Count Ilya Rostov/Tichon/Berthier/Ramballe/Beningsen - James Platt, Old Prince Bolkonsky - Jonathan May, Jacquot/Second General/Second Staff Officer/General Belliard/Second Lunatic/Yermolov - Donald Thomson, Dolokhov/Denisov/Raevsky/Napoleon - David Stout, Balaga/Kutuzov/Davoust/Old Grenadier - Simon Bailey, Metivier/Servant - Julian Boyce, Vasilisa/Housemaid - Carolyn Jackson, Gavrila/Matveyev/Valet - Laurence Cole, Joseph - George Newton Fitzgerald, Matriosha/Trishka - Sarah Pope, Monsieur de Beausset/French Abbé/First Lunatic - Joe Roche, Fyodor/Ivanov - Rhodri Prys Jones, Karataev/General Pyotr Konovnitsyn -Gareth Dafydd Morris, Orderly/Gerard/French Officer - Owen Webb, Shopkeeper - Paula Greenwood, Dancers (Juan Darío Sanz Yagüe, Ashley Bain, Meri Bonet, María Comes Sampedro, David Murley, Emily Piercy, Eilish Harmon-Beglan); Director - David Pountney, Tomáš Hanus - Conductor Set, designer - Robert Innes Hopkins, Costume designer - Marie-Jeanne Lecca, Lighting designer - Malcolm Rippeth, Visual projection design - David Haneke, Assistant director - Denni Sayers, Chorus and Orchestra of Welsh National Opera.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Tuesday 23rd July 2019.

[1] Tolstoy On War: Narrative Art and Historical Truth in “War and Peace”, edited by Rick McPeak and Donna Tussing Orwin (Cornell University Press, 2012).

image=http://www.operatoday.com/War%20and%20Peace%20title%20image.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=WNO perform Prokofiev’s War and Peace at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Cast and Chorus of Welsh National Opera

Photo credit: Clive Barda

Glyndebourne Announces the Return of the Glyndebourne Opera Cup in 2020

Stephen Langridge, Artistic Director of Glyndebourne , said: ‘The Glyndebourne Opera Cup seeks to find the most exciting young singers in opera. There should be no barriers to the expression of talent, but we have to recognise that in reality there are, and Glyndebourne is committed to removing as many as possible in order to make the Opera Cup as inclusive as it can be. We don't claim to have all the answers, nor do we think that we can do this on our own; we’ll be working closely with others to help us recruit a diverse pool of singers. By celebrating and supporting excellent young artists, we aim to show that opera is available for everyone and hope to inspire young singers of all backgrounds to see their future in this fabulous art form. The goal for all of us must be for the opera world to become a genuinely diverse artistic working environment, both on and off stage, which can better reflect the complex society in which we live.’

The inaugural Glyndebourne Opera Cup in 2018 was shortlisted for a Royal Television Society Award. The winner, American mezzo-soprano Samantha Hankey, will make her Metropolitan Opera debut this season and three of the 2018 finalists will perform at Glyndebourne in 2019 and 2020.

Building on the success of 2018, and with the continued support of Sky Arts, the focus in 2020 is on attracting exciting singers from all backgrounds. To do this the competition will:

· Visit twice as many international cities, with preliminary heats in London, Berlin, Paris, New York, Cape Town, Vienna and Milan

· Remove the economic barriers to entry with the offer of Sky Arts Bursaries to cover the costs of travel and accommodation to compete in the semi-final and final of the competition at Glyndebourne

· Launch a major social media campaign to drive awareness of the competition among a broad pool of potential applicants with the help of ambassadors from across the classical music world

Through the work of its education department, Glyndebourne is already delivering initiatives that target some of the systemic reasons for a lack of diversity in classical music. These include the Glyndebourne Academy, which offers training and support to singers who face challenges in pursuing a career such as personal circumstances, a lack of career guidance, limited access to skills development or financial barriers.

Philip Edgar-Jones, Director of Sky Arts , said: ‘At Sky Arts we are passionate about broadening out participation in every art form and finding new talent from diverse backgrounds; that’s why we are proud to partner with Glyndebourne on their second Opera Cup to help unearth the opera stars of the future.’

Julie Heathcote, Factory Films Executive Producer , said: ‘Factory are delighted to be again producing the Glyndebourne Opera Cup for Sky Arts. It was an honour to be part of the inaugural competition in 2018, and we loved helping to create a series that would entertain both newcomers to opera and the most ardent opera lovers. In March 2020, we’ll once again be broadcasting the finals live, bringing all the drama and excitement from Glyndebourne's beautiful auditorium to Sky’s audience at home. We can’t wait!’

The competition jury features representatives from top international opera houses along with leading singers, including British opera legends Sir Thomas Allen and Dame Felicity Lott and the GRAMMY Award-winning South Korean soprano Sumi Jo. Dame Janet Baker will once again act as honorary president. The jury includes:

· Stephen Langridge, Artistic Director of Glyndebourne

· Steven Naylor, Director of Artistic Administration, Glyndebourne

· Joan Matabosch, Artistic Director, Teatro Real de Madrid

· Michel Franck, General Director, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées

· Maria Mot, Associate Director, Vocal & Opera, Intermusica

· Sumi Jo, soprano

· Sir Thomas Allen, baritone

· Dame Felicity Lott, soprano

The competition focuses on selected composers or strands of the repertoire each time it is held. In 2020, singers will be invited to perform operatic arias by Mozart, Rossini and a selection of French 19th-century composers.

Applications for the Glyndebourne Opera Cup open on 1 September 2019. To be eligible, singers must be aged between 21-32 at the time of the final on 7 March 2020.

Visit glyndebourne.com.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Samantha%20Hankey%20with%20Dame%20Janet%20Baker.%20Photo%20Richard%20Hubert%20Smith.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title= product_by= product_id=Above: Samantha Hankey with Dame Janet Baker.Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith

July 23, 2019

'Secrets and Lies': a terrific double bill at Opera Holland Park

Written in 1909, the intermezzo’s neoclassical wit may be attuned to its time, but Wilkie updates the action to the 1940s and places it in a swish panelled apartment (sensibly pushing the action to the front of the long OHP stage) furnished with a gramophone, chaise-longue and cocktail cabinet that attest to its owner’s moneyed leisure.

The plot, like the secret, is simple. Newly married Susanna is afraid to confess to her non-smoking, older husband that she has a nicotine habit and so resorts to various wiles to keep her secret vice hidden. Smelling tobacco, Count Gil assumes that there is no smoke without fire and accuses her of infidelity. When he uncovers her subterfuge, they share a cigarette. Not very PC these days, when smoking seems to be more shameful than marital betrayal, but a perfectly droll amusette.

John Savournin (Sante). Photo credit: Opera Holland Park/Ali Wright.

John Savournin (Sante). Photo credit: Opera Holland Park/Ali Wright.

There’s a noticeable flavour of Fawlty Towers about the OHP proceedings, as two maids and John Savournin’s deliciously tongue-in-cheek, long-suffering manservant, Sante (a non-speaking role), dash about fulfilling domestic duties and maintaining domestic harmony.

Clare Presland’s Susanna is lyrical and light, but she works hard to project and finds a richer luxuriousness for the languorous aria, ‘O Gioia la Nube Leggera’, which sees her satisfy her Craven A craving and eulogise the nirvana of nicotine. Enrico Golisciani surely squandered his talents on libretto-writing, when the advertising industry, or Mills & Boon, might have reaped the rewards of his ripe repartee: “Oh, what a joy to follow with half-closed eyes, the fine cloud that rises in blue spirals, rises more delicately than a veil and seems like a golden illusion vanishing into the clear sky. The fine smoke caresses me, rocks me, makes me dream. I wish to taste your delight with a slow sweetness.”

Richard Burkhard (Count Gil) and Clare Presland (Countess Susanna). Photo credit: Opera Holland Park/Ali Wright.

Richard Burkhard (Count Gil) and Clare Presland (Countess Susanna). Photo credit: Opera Holland Park/Ali Wright.

Even though attired in a candyfloss-pink suit, Richard Burkhard sang with subtlety as Count Gil - no mean feat - moving swiftly through the speech-like passages and slipping suavely into more sumptuous mode for Gil’s extravagant paranoid outpourings.

If the opera requires two superb singing actors, then it also needs a conductor who can discern both the wit and the delicacy in the busy score and bring them deftly to the fore, which John Andrews did most tidily and stylishly at the helm of the City of London Sinfonia.

So, what to pair with the gossamer delights of Wolf-Ferrari’s trifle? Perhaps Ravel’s L’heure espagnole? Or, if one wants a more sombre counterpart, Poulenc’s tragic La voix humaine? Opera Holland Park plump for Tchaikovsky’s lyrical fairy-tale Iolanta, an altogether more dramatically, psychologically and musically ‘consequential’ work, and one which is far from ‘saccharine’.

Born blind, the princess Iolanta is kept ignorant of her disability by her father, King René, who confines her to the family’s estate and forbids all who come into contact with her to mention light or beauty in her presence. A sign above the gate to the garden threatens unwelcomed trespassers with death. When Iolanta’s betrothed, Robert Duke of Burgundy (who is unaware of her blindness and enamoured of another, Countess Mathilde of Lorrain) accidentally enters the King’s domain, with his friend Count Vaudémont, the latter is enchanted by the sleeping Iolanta. It’s a long journey from darkness to light but eventually, by dint of Vaudémont’s fortitude, the doctor Ibn-Hakia’s wisdom and the King’s forgiveness, Iolante’s gains the gifts of sight and light and love.

For an opera that closes with a choral rejoicing for God-given light, Olivia Fuchs’s production is an oddly dull and dismal visual affair: geometric slants replace garden scents and dangling lightbulb ropes substitute for rose trellises. Eschewing naturalism and the original locale, Fuchs and takis set the action in a 1940s hospital: Iolanta isn’t quite chained to the bed, but she might as well be … various drugs are administered to rend her unaware of her misfortunes and senseless of reality. Her nurse, Marta, robustly and warmly sung by Laura Woods, is a dour matronly figure straight out of Jane Eyre’s boarding school. The female chorus use bandages to cover their own eyes and gag their own voices. It’s grey and grim.

Natalya Romaniv (Iolanta) and David Butt Philip (Count Vaudémont). Photo credit: Opera Holland Park/Ali Wright.

Natalya Romaniv (Iolanta) and David Butt Philip (Count Vaudémont). Photo credit: Opera Holland Park/Ali Wright.

Fortunately, it’s Tchaikovsky’s emotionally charged Romanticism that calls the shots and drives the drama. More fortunately still, OHP has found a central pair of romantic leads made in heaven. Who needs Netrebko and Kaufmann, or Gheorgiu and Alagna, when we can have Natalya Romaniw (Iolanta) and David Butt Philip (Count Vaudémont), a veritable Romantic dream-team? They may have been attired in white shapeless nightdress and grey stuffy suit respectively, but their glorious singing was overflowing with the fresh, vivacious and sharply defined palette of the Baroque artists so beloved by the Pre-Raphaelites. The vocal brushstrokes were smooth, sustained and sumptuous. Both paced their characterisation and development effectively: their climactic duet was almost overwhelmingly impassioned and beautiful.

Ashley Riches (Ibj-Hakia). Photo credit: Opera Holland Park/Ali Wright.

Ashley Riches (Ibj-Hakia). Photo credit: Opera Holland Park/Ali Wright.