August 31, 2019

Prom 55: Handel's Jephtha

Ruth Smith’s assessment of Handel’s last wholly new oratorio, Jephtha, has not been shared by all her fellow Handel scholars. Composed by the aging composer in 1751, during a time when the onset of blindness forced Handel to put the score aside for a while, Jephtha has been criticised mainly on account of what is perceived to be Thomas Morell’s weak libretto. The substitution of a lieto fine courtesy of a descending angel for the Old Testament’s brutal sacrifice of a military hero’s daughter was judged by Paul Lang to be ‘nearly fatal to the oratorio’, and by Winton Dean to lend ‘a morbid emphasis on virginity’.

Interestingly, the story of Jephtha, the leader of the Israelites who inadvertently and tragically vows the sacrifice of his daughter after a victory against the heathen Ammonites, drew the attention of Voltaire (in the Philosophical Dictionary) who viewed it as confirmation that his ‘Enlightened’ contemporaries should strive for a civilised humanism in contrast to such biblical brutalities and barbarism (and as an opportunity to attack the Jesuits). But, as Smith has observed, Morell was a poet, an Anglican priest and a Doctor of Divinity, and as such was, in contrast, concerned to use the oratorio form as a ‘contribution to the defence of Christianity’.

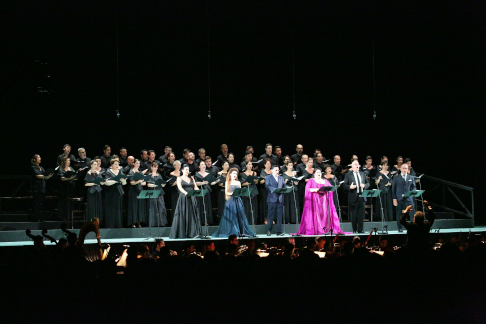

In this swift and sometimes rather stern Proms performance by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and SCO Chorus, conducted by Richard Egarr, such moral and theological issues were essentially by-the-by; and, as Egarr strove for energy and momentum perhaps, too, some of the work’s human anguish was glossed over, and the emotional interaction between the protagonists in this tragedy-turned-triumph weakened. But, this was still a compelling account, characterised by superb choral singing and the direct communication of events by a well-matched and accomplished team of soloists.

I haven’t always found that Handel’s oratorios and operas ‘work’ well in the Royal Albert Hall: last year’s Theodora (also with a libretto by Morell), for example, was somewhat lacking in dramatic impact and propulsion. On this occasion, sensibly, what I described as the ‘exquisitely beautiful poise and sensitivity’ of the period-instrument Arcangelo was replaced by the more urgent, impulsive and vibrant sound of the Scottish Chamber Orchestra - a sound which carried with more vigour, with punchy accentuation, strong dynamic contrasts and strikingly dark colourings at times, though Egarr ensured that the strings’ bowing was idiomatically stylish, and the tone did not lack Baroque bite.

Many numbers were omitted (particularly choruses - even one reproduced in the Proms programme was excised) and da capos were frequently truncated or deprived of their contrasting B sections - but the swiftness bestowed a freshness and resolve fitting for this dramatic episode from the Book of Judges, in which Jephtha accepts the Elders’ entreaty that he lead Israel in war against the tyrannical Ammonites on condition that he remain Israel’s leader after the war, and vows that if he is victorious then the first thing that greets him on his return home will be Jehovah’s, offered as a burnt sacrifice. Morell created additional characters - Storgè and Zebul, Jephtha's wife and brother respectively, and Hamor, a young soldier in love with Iphis (Jephtha’s daughter, so-named by Morell).

It was a pity, though, that the SCO Chorus’ contribution was curtailed, so spirited were they as priests, virgins and commentators, so vivid are Handel’s choruses. The diction of the collective was superb - no mean feat in the RAH - and each time the choric voices entered there was a dramatic and emotive ‘uplift’: from their first optimistic denunciation of the Ammonites whose demise they brightly anticipate; to the imitative intensity - wonderfully sculpted by Egarr - of the end-of-Act 1 pugnacious eagerness - coloured richly by the horns; to the skilfully balanced vocal reflections on the Lord’s decrees which follow Jephtha’s acknowledgement that his vow must be fulfilled. Here, the strings’ tight dotted-rhythms accrued a tension which exploded with the tenors’ and sopranos’ culminating vehement blast, “Whatever is, is right”. Emphasising, through silence and disjointedness, the shocking bluntness of this cry, Egarr paradoxically and provokingly suggested doubt rather than moral or theological certainty.

Cody Quattlebaum’s firm bass-baritone was the first solo voice that we heard and, as Zebul, his eloquence and directness was an engaging invitation to the drama. In the title role, Allan Clayton’s relaxed legato line conveyed an assured authority without imperiousness, though perhaps he did not entirely convince as a ‘military hero’. Egarr, almost hyperactive in his multi-role as harpsichordist, conductor and energiser, ensured that the SCO contributed much to the emotional spirit of the arias, and one could appreciate this in Jephtha’s Act 2 ‘Open thy marble jaws, O tomb’, when he realises the nature of the sacrifice his vow will compel him to make; here, the tautness of the unison strings’ rhythms and the darkly driving cello and bass line in the B section of the da capo conveyed all of victorious warrior’s inner conflict between resistance and submission. Similarly, reflecting on the pain that pierces “a father’s bleeding heart” when confronted with Iphis’ acceptance of her fate, Jephtha’s plaguing guilt was evoked by the strings’ full, emphatic pulsing beneath Clayton’s resolute melody. In contrast, ‘Waft her, angels, through the skies’ - one of Handel’s supreme, time-stopping melodies - unfurled with exquisite beauty and lightness.

As Hamor, counter-tenor Tim Mead was as, if not more, impressive, singing with sweetness and strength of his unfulfilled passion for Iphis’, and finding a wealth of colour in his duet with his beloved. In the latter role, soprano Jeanine De Bique displayed a pleasing tone and a clear focus, communicating a fitting purity and innocence but lacked variety of colour and nuance. Her final aria, ‘Farewell, ye limpid springs and floods’ did not suggest the inner torment that Iphis surely must feel, despite her avowed anticipation of heavenly peace.

Both De Bique and Hilary Summers struggled a little to project to the far reaches of the Hall, but Summers was a composed and very expressive Storgè, whose maternal reflections on the injustice of her daughter’s fate were compelling - again, the emotional import was underscored by Egarr’s encouragement of the double basses’ dark throbbing.

The ensembles were urgent, the Act II quartet surging segue from Hamor’s aria in which he offers his own life to save Iphis, and the Act III quintet bursting with joy. (Donald Burrows suggest that this quintet ‘All that is in Hamor mine’ - not ‘is mine’ as misprinted in the programme - is of doubtful authorship and was added in 1756.) The angelus ex machina had intervened in the form of Rowan Pierce’s sparkling, soaring saviour, promising Jephtha that he can fulfil his vow without sacrificing his daughter … if he dedicates her to God in ‘Pure, angelic, virgin-state’, for ever. One might question the ‘happiness’ of this ending, especially on Hamor’s behalf, but here the jubilant voices of the SCO Chorus rang out, rejoicingly, “in blessings manifold”.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Jephtha

Jephtha - Allan Clayton, Iphis - Jeanine De Bique, Storgè - Hilary Summers, Hamor - Tim Mead, Zebul - Cody Quattlebaum, Angel - Rowan Pierce, Conductor - Richard Egarr, Scottish Chamber Orchestra Chorus and Scottish Chamber Orchestra.

Royal Albert Hall, South Kensington, London; Friday 30th August 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/The%20Scottish%20Chamber%20Orchestra%2C%20SCO%20Chorus%2C%20conductor%20Richard%20Egarr%20and%20soloists.JPG image_description= product=yes product_title=Prom 55: The Scottish Chamber Orchestra, SCO Chorus, conductor Richard Egarr and soloists perform Handel’s Jephtha. product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: The Scottish Chamber Orchestra, SCO Chorus, conductor Richard Egarr and soloistsPhoto credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou

August 29, 2019

Opera della Luna's HMS Pinafore sails the seas at Wilton's Music Hall

As company founder and director Jeff Clarke explains in the programme for the show’s current tour, the company’s first 60-minute version of HMS Pinafore was designed for performance on board the QE2, in 1997. Performances for the Covent Garden Festival in 2000 and 2001 restored 20 minutes of the previously omitted material. When a decision was made, in 2001, to prepare a ‘full-length’ version with interval, the company determined upon the original 1878 version and ‘put back all the cuts, to preserve our stream-lined version as the core and to add a new interpolated opening and closing sequence’.

The resulting palimpsest, complete with some ‘judicious re-arrangement of the chorus material’, has been pleasing audiences ever since, and the punters at Wilton’s Music Hall showed their obvious delight, appreciation and approval during and after this lively rendition.

Some might like their satire served up in modern manifestation, but (sadly) some things never change, and the English class system can furnish twenty-first century humourists with as much idiocy and injustice for lampooning as their historical predecessors enjoyed. After all, the current Leader of the Commons is more commonly known as the Honourable Member for the 18th century.

Moreover, with mendacity seemingly the default mode of many of today’s politicians and leaders, the gentlemanly Captain Corcoran’s vacillation between truth and falsehood - “What, never?” CAPT.: “No, never!” ALL: “What, never?” CAPT.: “Hardly ever!” - seems absolutely in tune with the times. And, with Brexiteers blustering and rhapsodising along the lines of “We are a great nation and a great people”, it’s rather wry, though somewhat depressing, to be reminded by W.S. Gilbert that there have long been those who have failed to see the absurdity of regarding one’s nationality as an ‘achievement’ to be celebrated, rather than an accident of birth: as the ship’s crew joyfully crow of Able Seaman Ralph Rackstraw, “And it’s greatly to his credit/ That he is an Englishman! … For he might have been a Roosian,/ A French, or Turk, or Proosian, … But in spite of all temptations/ To belong to other nations,/ He remains an Englishman!”

In fact, Clarke moves the action not forward, but back, to the days of Dickens, justifying this transposition by reference to numerous Dickensian resonances: ‘One of Dickens’ Sketches by Boz tells of a snobbish resident by the name of Mrs Joseph Porter. Another describes a marine-store dealer in Seven Dials and lists the contents of his store: handkerchiefs, ribbons, a small tray containing silver watches, snuff, tobaccy boxes - in fact the very inventory of Buttercup’s stock.’ No ‘justification’ is really needed though, for if anyone was concerned with the efforts, and accompanying risks, of the lower strata of the middle class to rise from being tradesmen and upper servants, and the gap between the practices of this new commercial middle class and the principles of morality, then Dickens was.

At Wilton’s, the small cast of eight - there’s some doubling up for Sir Joseph’s various sisters and aunts - expended great energy and sustained a terrific pace. A naval tattoo (Graham Dare, percussion) gets the show underway and as pianist/musical director Michael Waldron and his sailor-suited six-piece band ripped through the overture, so the scattered ropes and tarpaulin were gathered, the ship’s rigging hoisted, and Pinafore made ready to set forth from her mooring bay in Portsmouth harbour.

Matthew Siveter impressed as Captain Corcoran, with his suave baritone, smooth phrasing and self-serving expediency: ‘I am the Captain’ found Siveter in particularly fine voice, and ‘Never Mind the Why and Wherefore’ saw him joined by an effervescent Josephine (Georgina Stalbow) and Graeme Henderson’s outlandish Sir Joseph in a refrain-reprising rejoicing that, threatening to roll on infinitely, took on the slightly desperate but deliciously madcap air of an Eric Morecambe routine.

Elsewhere Stalbow’s diction sometimes dissatisfied and she didn’t always have the heft to carry over the lively band - although, admittedly, I was seated very close to Waldron’s vigorous vamping - but she had plenty of glossiness at the top and her Josephine was warm-hearted. Henderson pushed the camp to the brink, and at times beyond, and brought a dictionary’s-worth of new meanings to the humble wink of an eye.

Louise Crane and Carolyn Allen worked hard, with sterling results, as Little Buttercup and Sir Joseph’s cousin Hebe respectively, while Lawrence Olsworth-Peter brought a youthful tone and a healthy dose of self-irony to the role of Ralph.

So, in summing up all that there’s really left to say is, “Now give three cheers …” for Opera della Luna!

Claire Seymour

Sir Joseph Porter - Graeme Henderson, Captain Corcoran - Matthew Sivester, Josephine - Georgina Stalbow, Ralph Rackstraw - Lawrence Olsworth-Peter, Little Buttercup/Sir Joseph’s sister - Louise Crane, Cousin Hebe - Carolyn Allen, Bill Bobstay - Martin George, Dick Deadeye/Sir Joseph’s aunt - John Lofthouse; Director - Jeff Clarke, Musical Director - Matthew Waldron, Set Designer - Graham Wynne, Costume Designer - Nigel Howard, Lighting Designer - Ian Wilson, Choreographer - Jenny Arnold, The ‘massed band of the Pinafore’ (violin - Rachel Davies, cello - Rosalind Acton, flute/piccolo - Gavin Morrison, clarinet - Simon Briggs, bassoon - Sinéad Frost, percussion - Graham Dare).

Wilton’s Music Hall, London; Wednesday 28th August 2019.

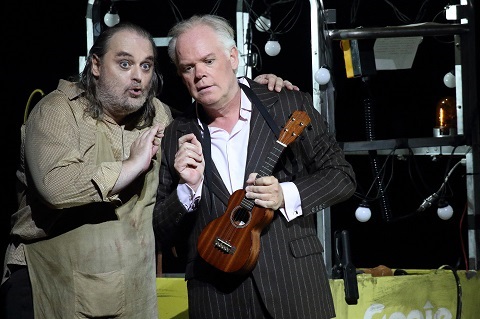

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Matthew%20Siveter%20and%20Louise%20Crane.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=HMS Pinafore: Opera della Luna at Wilton’s Music Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Matthew Siveter (Captain Corcoran) and Louise Crane (Little Buttercup)Spectra Ensemble present Treemonisha at Grimeborn

But, Joplin’s opera, for all its dramatic defects, is an important work, for musical and non-musical reasons, and it was good to see Spectra Ensemble bringing the work to the Grimeborn festival at the Arcola Theatre.

Initially labelled a ‘folk opera’, Treemonisha was subsequently described by its composer as ‘not ragtime … the score complete is grand opera’. In fact, the score mingles a quasi-Wagnerian palette with folk tunes, ballads, barbershop, gospel and even the music of the circus. Contemporary critics missed the point when they denigrated it as a poor imitation of European opera, for its hybridity might be seen as an attempt by ‘The King of Ragtime’ to forge a new, distinctly ‘American’ musical language, while its use of American themes, anticipates works such as Porgy and Bess, Oklahoma, and Carousel.

Written in 1911, set in Arkansas in the 1880s, and reflecting Joplin’s own experience as a young African American during the Reconstruction period, Treemonisha had to wait until more than fifty years after Joplin’s death for its premiere, at the Atlanta Memorial Arts Center on 28 th January 1972. It wasn’t the composer’s first opera: a single-act work comprising twelve ragtime tunes, A Guest of Honor, was completed in 1903 but Joplin’s publisher refused to publish it and there is no extant score. Joplin chose to publish Treemonisha himself and included a lengthy preface which provides details of the character and setting, and explains his ‘leitmotivic’ method.

Devon Harrison, Caroline Modiba, Deborah Aloba, Andrew Clarke, Aivale Cole and Grace Nyandoro. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Devon Harrison, Caroline Modiba, Deborah Aloba, Andrew Clarke, Aivale Cole and Grace Nyandoro. Photo credit: Robert Workman.

The opera is very much of its time, presenting a plantation community of freed slaves who fall prey to a ‘conjuror’, Zodzetrick, and his side-kick, Luddud, who exploit the simple folk’s gullibility and sell them ‘bags of luck’ to ward off evil spirits. The community is ‘saved’ by Treemonisha. Found under a tree, and adopted by a good-hearted couple - Ned, who manages the plantation for its white absentee landlord, and his wife Monisha - she has received an education from a white lady in town in exchange for her laundry services. She now sets about educating her fellow folk, challenging their superstitious beliefs. Fearful that Treemonisha’s enlightening effect will be bad for business, the conjurors first threaten and then abduct Treemonisha. She is rescued by one of her pupils, Remus, and, having urged her community to spare the kidnappers a brutal punishment, Treemonisha is then elected their leader.

The main studio at the Arcola Theatre is a challenging space within which to conjure a plantation deep in a forest in Arkansas. The brick walls of the former paint factory don’t lend themselves to a depiction of rural life, but director Cecilia Stinton and set/costume designer Raphaé Memon succeed in creating a credible, somewhat homey - and homely - community, by means of a few wooden crates and a paper tree-sculpture. But, figuratively, the ‘earth’ needs, I feel, to be a stronger presence: Stinton doesn’t draw out the community’s conflicting feelings, their joy at their new freedom being countered by a confusing love for the very land that once held them prisoner. Perhaps Ali Hunter’s lighting might have done more to evoke the colour and textures of the land?

With the musicians perched on the mezzanine above the thrust stage, Stinton makes effective use of the space beneath, and of the steps leading out of the auditorium, to suggest different locale, though briefly projected ‘titles’ might have been useful. Moreover, Joplin, who wrote both the score and libretto, distinguishes the characters by using dialect for the ‘uneducated’ folk, but whether the Spectra cast observed this distinction I could not tell, for the diction was not always clear.

Samantha Houston (Monisha) and Grace Nyandoro (Treemonisha). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Samantha Houston (Monisha) and Grace Nyandoro (Treemonisha). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

But, while some of the characters remained emblematic, others were given a dignity which raised them above stereotype. Grace Nyandoro’s soprano has a strength and a shine that conveyed Treemonisha’s integrity, vision and resilience, and her final acceptance of the leadership of the community was emotive and heart-warming. As Parson Alltalk, bass Rodney Earl Clarke delivered a powerful ‘sermon’, ‘Wrong is Never Right’, and doubled as a steadfast Ned, partnered by Samantha Houston as Monisha. The duet in which they tell Treemonisha of her origins was touching, though Houston did not, I felt, suggest the real melancholy that lingers in Joplin’s music. Zodzetrick was sung with power by Njabulo Madlada, his voice adding a touch of real menace that was largely missing from the production itself. Tenor Edwin Cotton struggled a little with the higher lying passages of Remus’s vocal lines, but acted spiritedly, while mezzo-soprano Caroline Modiba sang with fullness and smoothness as Lucy, Treemonisha’s friend.

There was a certain cautiousness about this first-night performance, though; the ensembles, in particular, were lacking in the sort of vigour that would have communicated the real spirit of the community, and the dances were somewhat conservative. ‘The Bag of Luck’ which introduces the main characters at the start of Act 1 should surely make a more vibrant impact. Perhaps it was just a case of opening night prudence: certainly, there was no hesitancy from the six musicians led by flautist/musical director Matthew Lynch, who played stylishly. Moreover, the light instrumentation (Joplin’s own orchestrated score is lost) created an intimacy complemented by the thrust stage.

Spectra Ensemble gave a good account of Joplin’s opera, but one which didn’t really explore or seek to reveal the African-American socio-political issues that Treemonisha addresses, as issues of race intersect with those of gender, class and sexuality. The opera celebrates education over ignorance and enlightenment over superstition, espousing American-Christian values, and many commentators have observed the broad associations between Treemonisha and the ‘uplift ideology’ of contemporaries such as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Joplin was an active member of at least one social-improvement organization, the Colored Vaudeville Benevolent Association, a charitable group founded in New York in 1909. And, after her husband’s death, Lottie Joplin eulogised that he ‘wanted to free his people from poverty, ignorance, and superstition, just like the heroine of his ragtime opera, Treemonisha’.

Stinton’s appealing but somewhat cosily sentimental production overlooked the undercurrents which give the opera - especially its closing chorus and dance, ‘A Real Slow Drag’ - its sad wistfulness. After all, as Rick Benjamin - conductor of New World Records’ centenary-celebrating recording in 2011, and a leading authority and interpreter of ragtime music - has observed, Treemonisha ‘is truly a rare artifact of a vanished culture: an opera about African-Americans of the Reconstruction era - created by a black man who actually lived through it’.

Claire Seymour

Scott Joplin: Treemonisha

Spectra Ensemble

Andy - Andrew Clarke, Ned/Parson Alltalk - Rodney Earl Clarke, Remus -

Edwin Cotton, Monisha -Samantha Houston, Zodzetrick - Njabulo Madlala,

Luddud - Denver Martin Smith, Lucy - Caroline Modiba, Treemonisha - Grace

Nyandoro, Chorus (Deborah Aloba, Aivale Cole, Devon Harrison); Director -

Cecilia Stinton, Music Director - Matthew Lynch, Designer - Raphaé Memon,

Lighting Designer - Ali Hunter, Choreographers - Caitlin Fretwell

Walsh/Ester Rudhart, Sarah Daramy-Williams/Elodie Chousmer-Howelles

(violin), Zara Hudson-Kozdoj (cello), Gwen Reed (double bass), Berginald

Rash (clarinet).

Grimeborn at the Arcola Theatre, London; Tuesday 27th August 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Grace%20Nyandoro%20%28Treemonisha%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Spectra Ensemble present Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha at Grimeborn product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Grace Nyandoro (Treemonisha)Photo credit: Robert Workman

August 28, 2019

Fortieth Anniversary Gala of the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro

Few of these globetrotters come for Pesaro’s mediocre restaurants, beaches or tourist sites. Nor is the venue special. In contrast to Macerata’s romantic outdoor space, this gala took place in a bland auditorium constructed inside a suburban multi-purpose arena named after a local producer of commercial refrigerators.

Everyone came to hear great performances of works by Gioachino Rossini, whose birthplace Pesaro is. The last four decades have witnessed a revolution in Rossinian performance-practice, based largely on new critical editions of lesser-known works and fresh insights into vocal style. Many of these innovations were pioneered at the Rossini Festival. What better place to assess the state of the Rossinian art?

Singing Rossini is harder than it seems. His operas may seem on the surface to be naïve and uncomplicated. Yet underneath lies much craft, cunning, wit, depth – as well as formidable technical difficulty. To portray all this with effortless charm poses exceptional challenges and opportunities for singers – and universally loved experiences for audiences.

This gala contained excerpts from Rossini’s most famous operas. The first half drew on three madcap comedies (Il Barbiere di Siviglia, La Cenerentola, and L’Italiana in Algeri) for which he is best known. These works bring to life enduring stereotypes of Italian life dating back to commedia dell’arte: the foolish old man, the conniving servant, the blustering military officer, the honorable gentleman, the greedy man of means, and the romantic young lover. After intermission, the evening continued with selections from two serious operas (Ermione and his culminating work for the stage , Guillaume Tell), heroic works of genuine idealism that set the stage for the more overtly political and romantic operas of Giuseppe Verdi.

The program was promising. Yet throughout the evening in Pesaro, the spirit of Rossini remained surprisingly elusive.

The tone was set from the start, with the Sinfonia (overture) to the Barbiere of Seville. Unlike the famous overture to Guillaume Tell, given a slightly more satisfying performance in the second half, this is not a concert piece as much as a farcical buffo aria. Each of its sections – grand chords, a bucolic melody, a plaintive complaint, a raging storm, two long crescendos, and a dashing finale – come pell-mell on top of one another, with no real underlying logic. To capture this crackling spirit, the formal correctness of Rossini’s musical language must be balanced with a sense of zany improvisation.

The Orchestra Sinfonia della RAI played reasonably well and some woodwind solos and the precise articulation of the upper strings were superb. Yet veteran conductor Carlo Rizzi encouraged them to play like a symphony orchestra, not a pit band. Torpid and unvarying tempos (rests carefully counted out), an earnest emphasis on sonic beauty, and an even dynamic drained the piece of all its wit and sparkle.

Much of the evening proceeded in this way, also on the vocal side. Singer after singer seemed unable to capture Rossini’s vivid and witty musical-dramatic caricatures. Franco Vassalio offered astonishingly dull versions – cautiously read from the music – of Rossini’s two greatest baritone arias: “Largo al factotum” (Barbiere) and “Sois immobile” (Guillaume Tell). The first lacked personality, the second pathos .

Paolo Bordogna’s account of Barolo’s archaic rant, “A un Dottor della mia sorte,” lacked appropriate vocal resonance (is he a bass at all?) or any inkling of how perfectly Rossini captured for all time the absurd futility of an angry dad lecturing a rebellious teenage girl. Bordogna suffered by comparison to veteran Michele Pertusi, who contributed only to the ensembles yet demonstrated clearly how resonant a genuine Italian bass should sound.

Russian mezzo Anna Goryachova and her tenor compatriot Ruzil Gatin (?), a last minute replacement, sang solidly but unremarkably: she produced resonant low tones and he harsh high ones.

Even American tenor Lawrence Brownlee, a wonderful singer at his best, seemed to be a bit off his game. One has to admire his courage in leading off with “Cessa di più resistere” from Barbiere – an aria so long and demanding that most tenors refuse ever to perform it. Yet Brownlee’s voice was pinched throughout and the opening segment off-pitch. In the slow romantic middle section, he recovered, phrasing with poignant delicacy, yet the vocal acrobatics in the finale were no more than solid.

It fell to the three remaining singers to save the evening.

Superstar Rossinian tenor Juan Diego Flórez contributed one showpiece to each half of the program, the elegant “Sì, ritrovarla io guiro” from Cenerentola and the heroic “Asile héréditaire” from Tell. Flórez is an assured vocal superstar: his rock-solid technique, accurate intonation, clear diction and, above all, ringing high “money notes.” In recent years, moreover, Flórez has enhanced his ability to sing softly with real musicality.

Yet whereas the first aria deserved the ringing ovation it received, the second disappointed. Flórez’s voice, impressive though it is within its natural domain, just seems too light for a role in which the orchestral sound and vocal demands verge on those of middle-period Verdi. Flórez seemed uncharacteristically cowed: at times he failed to penetrate the orchestra, his dynamics and tempi varied little, his pleas for Swiss patriots to “Suivez-moi” seem unpersuasive, and he cut short the final (interpolated) high C.

More impressive was Angela Meade, a leading bel canto soprano from the US state of Washington who has recently moved on to Verdi. With maturity, Meade’s voice has gained astonishing size and weight: in the inspirational final ensemble from Tell, her rich tone penetrated effortlessly to the back wall of the auditorium through five soloists, an orchestra and chorus, all at fortissimo. She sang each word and shaped each phrase (recitatives as much as arias and ensembles) with unabashed passion and musical-dramatic intelligence. Her scena from Ermione was marred only by a tendency to flat high notes.

Yet the highlight of the evening came at an unexpected moment midway through the first half. Sicilian baritone Nicola Alaimo, a Pesaro regular, strolled on stage and effortlessly performed the aria that opens Act II of Cenerentola. It is Rossini at his most wittily and cynically Italian: striving Don Magnifico dreams of marrying his daughter to an important man so he can live a life of cozy corruption, surrounded by supplicants who offer money (and more) in exchange for political favors.

For five minutes, Alaimo inhabited the scheming father with no inhibitions. I have heard versions with more accurate buffo patter and with high notes, but it did not matter. His gestures, almost conversational phrasing, and superb vocal acting captured the Rossinian spirit. Even a friend beside me who had never heard the aria and (given the lack of supertitles) did not comprehend a word, immediately felt the fleeting magic of the moment.

Overall, however, the 40th anniversary gala was uneven, giving as much cause for concern as celebration about the future of Rossini singing.

Andrew Moravcsik

image=http://www.operatoday.com/V12A8435.png image_description=Angela Meade [Photo by Studio Amati Bacciardi] product=yes product_title=Fortieth Anniversary Gala of the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro product_by=A review by Andrew Moravcsik product_id=Above: Angela MeadePhotos by Studio Amati Bacciardi

Berthold Goldschmidt: Beatrice Cenci, Bregenzer Festspiele

Sometime after Goldschmidt’s death, I found a trove of his recordings and those by other modern composers in a small local Oxfam. I bought as much as I could afford but told everyone. Suddenly, someone with more money than me swooped them all up. Later, talking to the composer Kalevi Aho, we deduced that the 200 or so CDs must have belonged to Goldschmidt himself since all the other composers were connected to his personal circle of associates. It may have been the clearance of his estate. Luckily, I did manage to grab what might have been Goldschmidt’s own copy of Beatrice Cenci, with Lothar Zagrosek conducting the Deutsches-symphonie Orchestra, Berlin, from the world premiere in August 1994, when Ian Bostridge sang the small part of the Page at the Villa Cenci orgy.

Goldschmidt’s Beatrice Cenci recounts a real-life scandal. Count Francesco Cenci, a renaissance nobleman, was fabulously rich, but violent. Because he was so powerful, he got away with raping his teenage daughter, Beatrice, who was eventually beheaded for killing him. Though Goldschmidt and his librettist based their version on a play by Percy Bysshe Shelley, the story is universal, and sadly, all too relevant to our times. Too much can be made of Goldschmidt’s connections with Weimar Germany, from which he emigrated aged only 33. He spent the next 60 years of his life in Britain. Beatrice Cenci is a work of its time, written for the 1951 Festival of Britain, when the concept of courage against injustice was recent memory. Goldschmidt maintained that his music was not programmatic but rooted in relationships with people and was particularly sensitive to the way that women were treated in patriarchal societies. “My works”, he wrote “have always come about as an interchange with the feminine in all its facets. That is the aura in which I compose”.

In Goldschmidt’s Beatrice Cenci, Count Cenci’s arrogant sense of entitlement is compounded by all around him, from his servants to the Courts and to the Papacy. The introduction is brief, but magnificent, but as anyone familiar with Schreker and Zemlinsky, Goldschmidt’s predecessors, will know, lush does not mean romantic. Almost immediately, sharp, tense chords intervene. Lucrezia’s (Dshamilja Kaiser) lines are shrill, rising high on the register, swooping downwards: an air of unsettled alarm. She’s Count Francesco’s second wife, not Beatrice’s mother, but she knows he’s a tyrant, and that wrong. Beatrice (sung by Gal James) at this stage has softer, less assertive tones. Bernardo (Cristina Bock), Beatrice’s full brother, is also cowed, burying his head on Beatrce’s lap. “Ours is an evil lot, and yet” sings Beatrice “let us make the most of it”. The cry of abused children, everywhere.

Enter Cardinal Camillo, (Per Bach Nissen) whose lines swagger, rolling figures built into the part, coiling like a snake. He’s covered up a murder for Cenci (sung by Christoph Pohl), both complicit in evil. Pohl’s baritone smoulders yet has a lethal edge: the character’s nasty business. Beatrice places her hopes in Orsino (Michael Laurenz) a young priest – forbidden territory! He’s in love with her, so offers to help her. At the Villa Cenci, princes and cardinals are replete after an orgy. Cenci sings “I too am flesh and blood and not a monster, as some would have me”. Yet he proudly announces that he’s killed all his sons. One was killed when a church collapsed on him, another knifed by a stranger, but Cenci’s not bothered. More wine, he calls, and blasphemes. Even Cardinal Camillo says Cenci’s insane, but Cenci threatens him, too. Now Beatrice takes courage, passionately begging the guests to save her from the palace. But Cenci isn’t scared. In a slithering tone he attempts to rape her again.

During the interlude, the open-air stage at Bregenz is filmed, darkness lit by sudden flashes of light – hiding yet alluding to the unspeakable. Lucrezia finds Beatrice, who has gone mad, cradling a doll. “I have endured a wrong so great that neither life nor death can give me rest – ask not what it is”. The voices of stepdaughter and stepmother intertwine, suggesting other unspoken horrors (Lucrezia’s quite young – the many adult children are not hers.) Beatrice talks Orsini into hiring hit men, to free Beatrice from her father. Count Cenci returns, but Lucrezia bars his way. On the Bregenz stage, Cenci wears a diamante penis, big enough that the audience far from the stage get an eyeful. Quietly, Lucrezia slips poison into his wine, and he falls asleep. The hit men come but their job is done, and they throw the body down a wall. Suddenly, Cardinal Camillo returns, surrounded by troops with a warrant for Cenci’s arrest. Concluding that Cenci was killed by Lucrezia and Beatrice, he has them taken off to prison.

Tolling bells introduce the final act. Bernardo and Beatrice are huddled together, Lucrezia with them. The henchmen Orsini hired give witness against Lucrezia, but Beatrice refuses to deny what has happened. “Say what you will, I shall deny no more”. From this point, Goldschmidt’s opera becomes more abstract, more “modern”, psychologically true rather than literal. A distant choir is heard. Cardinal Camillo says that the Pope has denied mercy. The sentence is death. Against the mysterious strains of an orchestral Nocturne, Lucrezia and Beatrice are seen, both crumpled like broken dolls. Beatrice now gets a chance to sing a “mad scene”, which is more poignant than deranged. “Sweet sleep were like death to me…O Welt, Lebewohl”, her words echoed by the orchestra.

A short but dramatic Zwischenspiel introduces the final scene. Carpenters are erecting a scaffold, the orchestra imitating their ferocious blows. An angry crowd gathers, and Lucrezia’s clothes get ripped off (she’s wearing a body suit, for the faint-hearted). Yet Beatrice is strangely calm. “Be constant to the faith that I though wrapped in the clouds of crime and shame lived forever holy and unstained”. Those who want blood and guts will be disappointed as the women just fall dead. But Cardinal Camillo is moved. “They have fulfilled their fate, guilty yet not guilty, thus do evil deed bring evil, crimes bring forth crimes”. He blesses them with a quiet Requiem Aeternum.

Bertold Goldschmidt’s opera is wonderfully taut, more chamber opera than regular opera, so I can imagine future productions that make the most of the claustrophobic atmosphere and the liberating release of death at the end, but this DVD – heard together with the often musically superior Lothar Zagrosek recording – should secure Beatrice Cenci its rightful place in modern repertoire.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Beatrice_Cenci_DVD.png image_description=C Major 751504 product=yes product_title=Berthold Goldschmidt: Beatrice Cenci (1950) product_by=Gal James, Christoph Pohl, Dshamilja Kaiser, Christina Bock, Prague Philharmonic Choir. Wiener Symphoniker. Johannes Debus, conducting. product_id=C Major 751504 [DVD] price=$31.99 product_url=https://amzn.to/2KZApWLAugust 27, 2019

Verdi Treasures from Milan’s Ricordi Archive make US debut

The exhibition traces the genesis and realization of Verdi’s last two operas, Otello and Falstaff, using original scores, libretti, selected correspondence, set and costume designs, and more. Giuseppe Verdi - alongside Giacomo Puccini, Gaetano Donizetti, Vincenzo Bellini, and Gioachino Rossini - is one of the five great names of 19th century Italian opera whose works were published by Casa Ricordi and documented in its Archivio Storico Ricordi. The Ricordi Archive is regarded as one of the world’s foremost privately owned music collections. The Morgan Library & Museum complements the exhibition with rarities from its own collection, including early editions of texts by William Shakespeare, whose dramaturgical material served as the basis for the operas Otello and Falstaff.

This combination of materials from the two great institutions under the guidance of curators Fran Barulich and Gabriele Dotto gives visitors a unique opportunity to gain first-hand insights into the European cultural scene of the late 19th century. The supporting program of the exhibition also includes a concert with Verdi arias, a screening of Franco Zeffirellis Otello, and a lecture with experts from the Ricordi Archive.

Colin B. Bailey, Director of the Morgan Library & Museum, said: “We are delighted to present these highlights from the Ricordi Archive, showing how Italy’s pre-eminent composer shaped what would become two of his crowning achievements, Otello and Falstaff. A collection of set designs, costumes from Milan’s Teatro alla Scala, autograph manuscripts, contracts, publications, publicity, video excerpts from recent productions, as well as objects from the Morgan’s collection enable visitors to experience the tremendous collaborative efforts behind an operatic production.”

Thomas Rabe, Chairman & CEO of Bertelsmann, said: “The name Ricordi stands for 200 years of Italian opera and music history. As the owners of the Ricordi Archive, we are very aware of the importance of this European cultural asset and take responsibility for its sustained preservation, care and development. Exhibitions like the one in New York, in partnership with the Morgan Library, are a great opportunity to keep the creative work of earlier generations alive and to reach audiences beyond the musicological community.”

The richly textured exhibition “Verdi: Creating Otello and Falstaff - Highlights from the Ricordi Archive” describes the creative process of the two world-famous operas - from initial deliberations about commissioning the celebrated composer to the premieres of Otello in 1887 and Falstaff in 1893. The idea for Otello first arose in 1879, when Verdi was 65, but he did not begin to work on the project in earnest for several more years, when he was in his 70s. There was almost a 16-year hiatus between the 1887 premiere of Otello and the 1871 premiere of Aida. His Milanese publisher Giulio Ricordi teamed up with the librettist Arrigo Boito to develop a diplomatic strategy for luring “the old bear” out of retirement at his country home in Sant’Agata. Their plan worked, and applying his mature compositional skills to two brilliant libretti by Boito, Verdi created two of the greatest operas ever composed. Giulio Ricordi was ultimately responsible for marketing and managing the two large-scale productions. The exhibition thus provides a deep insight into the work of three geniuses who formed a kind of “business community.”

The partnership with the Morgan Library & Museum offers additional material that enriches the Ricordi exhibition: Shakespeare’s First and Second Folios, rare editions of scores and libretti, contemporary publicity material, an autograph letter from Verdi’s wife, and autograph sketches for Otello.

The New York exhibition represents a new milestone in the presentation of the Ricordi Archive to the public: In Verdi Year 2013 - the composer’s bicentennial - the archive’s treasures were first presented in Germany as the curtain-raiser to a traveling exhibition that toured Europe. At the time, the “Enterprise of Opera: Verdi. Boito. Ricordi” exhibition was shown in Berlin and Gütersloh and subsequently in Brussels, Milan and Vincenza. It now forms the basis for the forthcoming exhibition in New York.

The Ricordi Archive houses a total of some 7,800 original scores from more than 600 operas and hundreds of other compositions; approximately 10,000 libretti; an extensive iconographic collection with precious original stage and costume designs; and a vast amount of historical business correspondence of Casa Ricordi. Founded in 1808 by Giovanni Ricordi in Milan, the Italian music publisher had a fundamental influence on the cultural history of Italy and Europe. Bertelsmann, the international media company which also includes the BMG music group and the New York-based trade publishing group Penguin Random House, bought Casa Ricordi in 1994, but sold the music company and Ricordi’s music rights in subsequent years. Only the associated Ricordi Archive remained within the group. Since then, Bertelsmann has had the archived items comprehensively indexed, digitized and, in many cases, restored. The company also organizes concerts and exhibitions to keep Casa Ricordi’s cultural heritage alive and make it accessible to as many people as possible.

Programs:

· Gallery Talks “Verdi: Creating Otello and Falstaff - Highlights from the Ricordi Archive” Friday, September 13, 6pm Friday, November 15, 1pm

· Films, “Otello” Friday, September 20, 7:00pm; “Tosca’s Kiss” Friday, October 18, 7:00 pm

· Family Program Curtain’s Up! Theatrical Design at the Morgan Saturday, September 21, 11:00 am Dance: Inspired by Verdi Saturday, November 9, 2:00pm

· Concerts George London Foundation Recitals Sunday, October 20, 4:00pm

· Lectures and Discussions “Verdi and the Ricordi Archive”: An Evening with Pierluigi Ledda and Gabrielle Dotto Wednesday, October 2, 6:30pm “Le Conversazioni: Films of My Life” Thursday December 5, 7:00pm

For more information about the exhibition, hours, and admission, visit www.themorgan.org.

For more information about the Ricordi Archive visit https://www.archivioricordi.com/en or https://www.bertelsmann.com.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ricordi_3141c%20%283%29.jpgAugust 26, 2019

Bel Canto Beauty at St George's Hanover Square: Bellini's Beatrice di Tenda

Same librettist, though. Sadly, circumstances and haste compelled Felice Romani to resort to self-recycling in a manner which deprived the characters of substance and development, and substituted contrivance for dramatic credibility. Struggling to fulfil his role as poet-in-residence at Teatro alla Scala, and with premieres also scheduled for La Parma and Florence, Romani began work on a libretto on Bellini’s initially preferred subject of Queen Christina of Sweden, only for the composer to change his mind. Bellini was influenced by Giuditta Pasta who proposed an opera on the tragic tale of Beatrice Lascaris di Tenda - the wife of Filippo Maria Visconti who succeeded his murdered brother to the Duchy of Milan and used his wife’s personal resources to extend his demesne, before becoming jealous of her first husband’s reputation as a noble soldier and hatching a plot to have Beatrice convicted of adultery and, alongside her supporters, executed.

Romani’s progress was dilatory; the premiere was delayed; a professional partnership and friendship was irreparably damaged. By the time Romani had provided Bellini with a text which essentially translated the amorous and political intrigues of the sixteenth-century Tudor court to fifteenth-century Milan, the public’s hackles were already sharpened and Beatrice di Tenda received a negative reception at its premiere. A public blame-game played by mud-slinging backers of Bellini and Romani followed, and although subsequently attitudes softened, and the opera was heard across Europe, in the US and in Latin America in the ensuing 20 years, thereafter it disappeared into the operatic hinterland.

Ironically, Beatrice di Tenda is well-suited both to a concert staging and for performance by young soloists well-schooled in the art of bel canto singing, as was the case at St George’s Church Hanover Square at the second of two performances which closed the 2019 London Bel Canto Festival. Under its Artistic Director, Ken Querns Langley , a singer, teacher and researcher of bel canto, the Festival serves an academy for young singers to learn bel canto technique and idiom, offers the public an opportunity to hear performances by bel canto trained voices, and supports the creation of new music. The soloists and members of the Chorus had enjoyed masterclasses with Bruce Ford, Nelly Miricioiu and Langley himself, and other events during the 20-day Festival included a ‘Come and Sing’, enabling the public to work on the choruses in Beatrice, a panel-discussion and a gala concert at the National Liberal Club in Whitehall.

The plot is straightforward and the denouement inevitable: Beatrice is married to Filippo who desires the younger Agnese del Maino; the latter is in love with the courtier Orombello, who in turn adores Beatrice. Fearful of a popular uprising in support of Beatrice, Filippo has Orombello and Beatrice imprisoned in the Castle of Binasco; under torture, Orombello confesses to adultery. A tribunal is convened, and despite the guilt with briefly troubles both Agnese and Filippo’s, the Duke’s fear that troops loyal to Beatrice will storm the castle walls leads him to sign her death warrant. She accepts her fate, forgives the repentant Agnese and declares herself ready for death.

The cast worked hard and with considerable success to establish character, dramatic shape and tension. Despite the spatial limitations of the venue, they made full use of St George’s aisles and balconies. It helped, too, that - excepting Brian Hotchkin (Filippo) - they all sang largely and confidently off-score. It was a pity that the music stands, rather redundant for much of the time, were spread so widely, for this discouraged the sort of interaction that, when the singers took things into their own hands and moved towards the centre, lifted the dramatic temperature considerably.

The role of Beatrice is dramatically limited, dignified victimhood being her default mode, but the vocal demands are considerable. Australian soprano Livia Brash has a richly upholstered and luxuriantly coloured lirico-dramtico soprano and she exhibited range, strength and nuance, rising with considerable power in the ensembles and showing stamina in arias whose tessitura is frequently high. Her control and accuracy were less consistent, however; some of the coloratura was a little blurry, especially in the double-aria finale - though she can be forgiven for tiring a little at the close - and the intonation was not always spot-on, with notes sometimes approached from beneath, or wavering when sustained. But, overall, Brash’s was an impressive performance of considerable commitment and accomplishment, and one from which she clearly derived enormous pleasure and fulfilment.

On 22nd July the title role had been taken by Danish soprano Simone Victor who, at the Gala concert the following evening, gave a beautiful performance - self-composed yet imbued with feeling - of Beatrice’s first aria, ‘Ma la sola’, in which the Queen laments Filippo’s waning affection.

Given that she is still a student (at Stephen F. Austin State University, where she is studying Music Education), American mezzo-soprano Taryn Surratt really impressed as Agnese. Romani doesn’t give the singer of this role much help: potentially Agnese is riven by complex emotions - blinded by love to act with selfish cruelty, but later beset by a remorse which compels her to confess - but after an initial aria and duet at the start of Act 1, she’s little more than one voice among many in the long Act 1 finale and Act 2’s trial scene, and there is - an opportunity missed, surely - no substantial confrontation between the two women at the close. Surratt made the utmost of what she was given though; her mezzo has lustre, focus and an ear-pleasing timbre, and she displayed a graceful turn of phrase, making the most of any melodic expansiveness. She had shown similar poise and control when singing the first performance of Clara Fiedler’s ‘Cards and Kisses’ at the Gala Concert, a setting of a light-hearted poem by the Elizabeth poet John Lyly for piano and countertenor/alto: an example of the Festival’s development of new works which enable singers to express bel canto vocal principles in modern settings.

Filippo is undoubtedly a nasty piece of work: the challenge is to make him more than just a black-hearted villain, and this requires a firm but agile baritone that can impose a steely authority, intimate cruelty, and convey both repressed feeling and inner doubt. Hotchkin’s performance had many merits, not least its intimation of Filippo’s stubborn tyranny in the face of real or imagined threats to his power - Hotchkin, removing his glasses, can deliver a mean stare. But, there’s a risk that Filippo can become rather monotonal and slip into a relentless rant, and this danger wasn’t entirely avoided here. As far as one can tell in a concert staging, Hotchkin is not a natural actor, added to which, when he needed to relax and sing through the legato line, his jaw seemed to tighten, resulting during Filippo’s bellowing in a rather flannelly tone. He also struggled with role’s upper-lying forays. That said, Hotchkin did conjure the Duke’s inner distress in the death-warrant scene and his long confessional aria was well-shaped.

Beatrice’s devoted Orombello isn’t rewarded with an aria of his own - the role was first taken by Alberico Curioni whose death, as Rossini's Otello, was greeted with shouts of ‘May he not rise again!’, which may account for Bellini’s reluctance to entrust him with a role of substance - but that didn’t stop Mexican-Canadian tenor Sergio Augusto from making Orombello’s involvement in duets and ensembles vigorous, convincing and impassioned. Augusto can turn from ardency to melancholy with ease, and his single excursion into the upper reaches was securely and confidently pulled off. The minor roles of Rizzardo (Agnese's brother) and Anichino (Orombello’s friend) do little more than fulfil the need for someone to say the lines that advance the plot, but they were well sung by Indian baritone Shakti Pherwani and Iranian-born tenor Sam Elmi, respectively.

Conducting a technically secure and musically alert London City Philharmonic Orchestra, Olsi Qinami’s no-nonsense approach built the scenes effectively, particularly the long trial scene leading to Filippo’s judgement. The strings were tidy and sweet-toned, despite the general darkness of the score, and the orchestra clearly boasts an impressive woodwind and horn section. But, it was a pity that Qinami did not quieten the massed forces at the dramatic climaxes: the twelve-strong Chorus struggled to carry across the instrumental maelstrom and soloists were forced to burst their lungs and vocal chords in an attempt to surf the orchestral crests. In the quieter passages, though, the Chorus’s contribution gave much pleasure and they made a good job of embodying a multitude of group personas which often play a considerable role in the plot machinations.

For all the flaws in dramatic structure and music-text alliance, this performance convinced me that there is not a single aria, duet or ensemble in Beatrice di Tenda in which Bellini’s powers were not operating smoothly. Perhaps companies such as Chelsea Opera Group might take note?

Claire Seymour

Beatrice - Livia Brash, Filippo - Brian Hotchkin, Agnese - Taryn Surratt, Orombello - Sergio Augusto, Anichino - Sam Elmi, Rizzardo - Shakti Pherwani, Conductor - Olsi Quinam, London City Philharmonic Orchestra.

St George’s Church, Hanover Square, London; Saturday 24th August 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/London%20Bel%20Canto%20logo.jpgAugust 25, 2019

Semiramide at the Rossini Opera Festival

That’s four solid hours of music — six arias and four duets (plus an introduction and two finales). Rossini scholar Philip Gossett asserts that Rossini will have never heard this, his last tragedy, performed uncut. We owe the privilege of hearing every last note to the Rossini Opera Festival which is obviously obliged to perform the entirety of its critical editions.

It was a long evening, very long, and a surplus of pleasure, notably two splendid singers, Georgian soprano Salome Jicia as Semiramide and Armenian mezzo soprano Varduhi Abrahamyan. Both singers made big impressions in their Pesaro debuts, the 2016 La donna del lago, and they return now with even more confidence and fully mature techniques.

Adding to the evening’s glamour was Pesaro conductor Michele Mariotti, son of Gianfranco Mariotti founder of the Rossini Opera Festival. Though rarely on the podium at the Rossini Opera Festival, conductor Mariotti is often on the podiums of the world’s most prestigious opera houses and festivals. Mo. Mariotti brings impeccable taste to informed contemporary Rossini style, and a musical confidence that pervades every moment on the stage.

Unlike most Rossini operas Semiramide possesses an elaborate overture (double winds plus four horns and three trombones as well!) that is specific to its musical content. It unfolds in a sumptuous horn quartet duet with the two bassoons, it makes surprising effects with its piccolo solos and it well exploits Rossini’s love of playfully passing lines between the woodwinds. Mo. Mariotti’s overture deservedly earned one of the evening’s hugest ovations.

Semiramide is the shocking story of a queen who was an adulteress, a murderess and guilty of incest as well. Maybe back in 800 BC the story was historical fact, but nearly all subsequent Western civilizations have put their spin on its happenings, including Rossini’s librettist Gaetano Rossi who rendered it into the thirteen musical numbers that offer singers with spectacular techniques the chance to show-off.

Varduhi Abrahamyan as Arsace, priests and partially hidden teddybear

Varduhi Abrahamyan as Arsace, priests and partially hidden teddybear

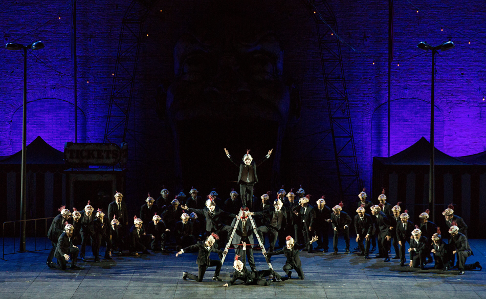

Just now in Pesaro stage director Graham Vick brought Rossini’s Semiramide into the twenty-first century playing heavily on contemporary sexual ambiguities, and teasing us with a huge, cartoon teddybear image to remind us that an innocent young child is mixed up in the story’s brutality. The entire four hours unfolded under or within the age-withered gaze of the man Semiramide murdered — her husband, the king Nino, the father of her son — and the reverse side of that huge image (the two stage wagons were turned around) where childish drawings were scribbled on the blank surfaces between the wagons’ structural supports.

The stage metaphor was of utmost simplicity, but reeked of theatrical complexity. We understood that Rossini’s musical language was transformed into a language of contemporary theater, and that it spoke to us not as a straightforward locale in which Rossini’s singers sing, but as the world we live in, where we feel and know but that we do not define.

Semiramide wore pants, high heels and a severe short haircut. She was a powerful woman who dominated men and their destinies. The young general Arsace wore a black pants suit with only a gold shoulder braid to indicate military rank, and with ample décolletage to boast a well endowed female breast. The sexual tension of forbidden desire rose to a nearly unbearable level as we watched and listened to these two young, powerful women negotiate their famed duet "Serbami ognor si fido il cor."

The high priest Oroe, bass Carlo Cigni, connects Graham Vick’s post modern world to a netherworld. He was some sort of high priest (guru) of a primitive culture having, supposedly, greater access to the earth’s truths. He had a number of similar undressed acolytes who made the fawning motions of clueless cult followers, mindlessness that echoed the innocence of the teddybear. Oroe’s dictums from the netherworld caused many, but hardly all of the problems.

Semiramide’s daughter Azema appeared in virginal white standing high at the side of the stage under a childish scribble of the sun. She was the contested prize (the prize includes becoming king of Assyria). She has little to sing in Semiramide’s ten arias and duets. The contenders for the throne are an Assyrian prince, Azzur, dressed like an early twentieth century Prussian prince, and an Indian king, Idreno, dressed as an exotic Indian king. Both of these men of course have a lot to sing about over then next few hours.

Antonino Siragusa as Idremo, priest supernumeraries in foreground

Antonino Siragusa as Idremo, priest supernumeraries in foreground

Here’s the catch: Rossini and his librettist established a basic four part model for all of Semiramide’s arias and duets, beginning with a cantabile (melodic) section followed by a chorus and recitative that changes the situation. Then there is the cabaletta (a livelier reaction to the situation), and finally a repetition of the cabaletta wherein the singer shows his stuff (added ornamentation). This is a long, drawn out process (and there were ten of them) that at best allowed us to know each of the characters and to know its singer. And at worst to tire us beyond caring.

The matricide that ends the opera packed a wallop. We did indeed know Semiramide and her son Ninia who had become the general Arsace. Even knowing Semiramide’s nefarious actions we still did care about this tragic queen, and we did feel the complexity of emotion that gripped Arsace in murdering his mother. The tragic irony that made him Assyria’s king hung heavily.

Far more than staging an evening of brilliant singing director Graham Vick created an event of monumental tragedy. It was effected by the brilliant singing and acting of Salome Jicia as Semiramide and Varduhi Abrahamyan as Arsace. Rossini’s melodramma tragico was in fact a quite successful sung tragedy.

The splendid cast included the Azzur of Argentine baritone Nahuel di Pierro and the Idreno of tenorino Antonino Siragusa as the rivals for the hand of Semiramide’s daughter Azema sung by Romanian mezzo-soprano Martiniana Antonie. Bass Carlo Cigni sang the high priest Oroe and Russian bass Sergey Artamonov sang the two brief interruptions of the ghost of the murdered king Nino. The captain of the royal guard, Mitrane, was sung by Alessandro Luciano.

Mr. Vick's associates in creating this production were his long time collaborators Stuart Nunn (sets and costumes) and Giuseppe di Iorio (lighting).

The performances took place in the Vitrifrigo Arena (Vitrifrigo is a Pesaro company that makes miniature refrigerators and freezers), formerly the Adriatic Arena. I attended the third of four performances on August 20, 2019.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Semiramide_Pesaro1.png

product=yes

product_title=Semiramide in Pesaro

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Varduhi Abraramyan as Arsace, Salome Jicia as Semiramide [All photos copyright Rossini Opera Festival, Pesaro]

August 23, 2019

L’equivoco stravagante in Pesaro

She loves her fiancé for his looks and her tutor for his learning. A well meaning servant spreads the rumor that she is really a castrato male posing as a female to avoid military service. Its two acts are essentially three or more easily imagined farces.

Rossini began working in opera houses at the tender age of nine, thus he absorbed an already formulated and very rich opera buffa tradition. Just now in Pesaro from the first notes of the overture conductor Carlo Rizzi discovered the unique Rossini beat and fanned hints of the famed Rossini crescendo [like, sort of, Ravel’s Bolero only infinitely faster], and unveiled the melodic inflections that presage the great Rossini. It was the same overture Rossini had used for his first farce, La cambiale di matrimonio (1810) and that he would use again for his opera seria Adelaide di Borgogna (1817).

With the exception of a fine quartet and then a truly delightful quintet in the first act, and Ernestina’s rondo in the second act the musical numbers are generic buffa. Of far greater interest is the libretto, by one Gaetano Gasbarri whose day job was as registrar of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (the program booklet is very informative). First and foremost Sig. Gasbarri’s libretto is a spoof of exalted literary language, and second and foremost as well it is a compendium of sexual innuendo and double entendre. The censors axed the production after only three performances.

But not before the combination of musical genius and licentious scandal had brought Rossini his first fame.

For the occasion the Rossini Opera Festival added supertitles (that are not always provided), and for the very international audience even duplicated the supertitles in English, a first! Of course the words fly by at a speed that precludes getting your mind around verbal subtlety, but we did pick up enough to be greatly amused. The pleasure and reported displeasure of the audiences for those three 1811 performances in the more intimate spaces of Bologna’s Teatro del Corso can only be imagined. [This grand old theater was destroyed in 1944 by a WWII bomb — Bologna was a fascist stronghold.]

The Rossini Festival invested considerable artistic capital in the production besides conductor Rizzi, namely the French stage director team Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier, noted for their precise, conceptual minimalism. The single unit set was a wall making a symmetrically broken line, covered with a repeated, regal pattern upon which there was a grandiose painting of several cows (Ernestina’s father was a nouveau riche farmer). The first act was animated by tasteless, often obscene physical gestures. In the second act the set itself did some tricks that were amusing thus relieving somewhat the visual boredom and enlivening the farcical storytelling.

Ernestina and Buralicchio

Ernestina and Buralicchio

Of equal point were the costumes, most notably the additions of prosthetic noses added to all the faces, thus making sure that we accepted the personages as bizarre (we did indeed). To great effect was the artificially puffed out chest and thrust back butt (the rooster strut) of Ernestina's rich fiance Buralicchio well matching the three grandly laced tiers and frilly décolletage of Ernestina’s very big white dress. Enestina’s father Gamberotto was in a fat suit extolling the pleasures of his wealth, and Ermanno, her tutor was in the clearer colored, slimmer fitting clothes of the victorious suitor.

Buralicchio comes to believe that Ernestina is a male, though Ermanno has not yet heard the rumor and effects a bedroom tryst with Ernestina. We too began to see male characteristics in Ernestina, and in the duet we began to confuse the tenor voice with the mezzo (contralto) voice. The very informative program booklet tells us that the part of Ernestina was composed for a famous contralto named Maria Marcolini, of reported androgynous voice. In fact the tessitura in which Ernestina sings is often in virile territory — mezzos at that time were the descendants of castrati (and there were still plenty of real castrati around).

Ermanno, Ernestina, Buralicchio and Gamberotto

Ermanno, Ernestina, Buralicchio and Gamberotto

L’equivoco stravagante

was brilliantly cast. Mezzo soprano Teresa Iervolino could produce those virile tones, and as well move into the higher reaches where she managed effective mezzo-soprano fioratura. Her movements hinted at the clumsiness of a male impersonating a female. Bass baritone Paolo Bordogna was the indefatigable Gamberotto, a splendid basso buffo well known to Pesaro audiences. Though you might have expected the patter from Gamberotto, Rossini instead assigned it to the Buralicchio where it was well integrated into Davide Luciano's strutting. Russian tenor Pavel Kolgatin ably executed the florid lines of the tutor Ermanno.Not to forget the opera buffa’s two stock trouble makers, the servants Rosalia sung by Claudia Muschio and Frontino sung by Manuel Amati.

Michael Milenski

Production information:

Production information:The chorus of the Teatro Ventidio Basso (Ascoli Piceno); the Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale Della RAI (Torino). Conductor: Carlo Rizzi; Stage Directors; Moshe Leiser and Patrice Caurier, Sets: Christian Fenouillat; Costimes: Agostino Cavalca; Lights: Christop;he Forey. Vitrifrigo Arena (formerly the Adriatic Arena), Pesaro, Italy. August 19, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Equivoco_Pesaro1.png

product=yes

product_title=L'equivoco stravagante at the Rossini Opera Festival, Pesaro

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Teresa Iervolino as Ernestina, Paolo Bordogna as Gamberotto [All photos copyright Rossini Opera Festival, Pesaro]

August 22, 2019

BBC Prom 44: Rattle conjures a blistering Belshazzar’s Feast

It was very much a ‘pictures in sound’ affair, an orchestral and choral jamboree variously capturing the atmosphere of tropical forest, city soundscape and Babylonian excess in three 20th century works, all given efficient direction by Sir Simon Rattle.

The evening began with Charles Koechlin’s rarely heard symphonic poem Les bandar-log, an evocative and eclectic orchestral realisation (a ‘monkey scherzo’) completed in 1940 and inspired by a French translation of Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book which appeared at the turn of the century. Koechlin’s outsize orchestra is often used sparingly with numerous chamber sonorities (including one extraordinary passage for strings employing six different keys) and in his idiomatic portrayal of a troupe of monkeys the composer constructs a satire on newfangled modes and manners of contemporary music, travelling in time to mock French impressionism, serialism and neoclassicism (in the shape of a rather dull fugue). It’s an anarchic and virtuosic score brimming with invention that glows with febrile excitement and mystery, all conveyed with a wry wit from Rattle and a gleefully committed orchestra - the percussion section in their element.

Another seldom heard score followed with Edgard Varèse’s Amériques given here for the first time in its original 1921 version. Often referred to as an urban Rite of Spring, Amériques is an audaciously futuristic work (just as Charles Ives’s Central Park in the Dark was in 1906) which references both Stravinsky and Schoenberg. It’s a vast love poem to Varèse's adopted country, specifically New York where, from his apartment, he could hear “the whole wonderful river symphony which moved me more than anything ever had before”. There was no shortage of evocative shrieks and wailings from an 18-string percussion section, including two wind machines, which with other expanded instrumental groups collectively brought to life the city’s frenzied-sounding activity. But its twenty-five minutes seemed over long, the great sound masses, mechanistic power and loneliness of a distant trumpet (bringing to mind Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks) didn’t quite have the impact I’d anticipated - certainly no deafening onslaught, more a repetitious assemblage of newly-minted sonorities that ultimately outstayed their welcome despite orchestral playing of energy and precision.

This last quality was mostly realised in Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast for which the composer devised a score of grand proportions (though not as wildly ambitious as Havergal Brian’s ‘Gothic’ Symphony from a few years earlier) including two (antiphonally placed) brass bands which had been rashly suggested by Sir Thomas Beecham prior to the work’s Leeds premiere in 1931. Next to Koechlin and Varèse’, Belshazzar’s Feast seemed almost rather ordinary, yet to pull off this extraordinary work with the necessary degree of conviction is no small ask. By and large it all worked, but even with the combined voices of the adult and youth choirs of Orfeó Català and the London Symphony Chorus their contribution felt occasionally underpowered and the brief semi-chorus passage was not quite as confidently delivered as it might have been. That said, the opening was strikingly assured, with plenty of heft from the men’s voices and the lament of the Jews had just the right degree of fervour. It was the singing of the more jubilant choral writing that never quite convinced, lacking absolute crispness that would otherwise have brought compelling rigour to the proceedings. It didn’t help that Rattle pushed a little too hard for the closing ‘Alleluias’. Yet there were some bewitching moments, not least the jazzy rhythms (finely sung) and ear-tickling percussion that accompanied the worship of the Gods and the haunting writing on the wall with an arrestingly choral “slain”.

Gerald Finley brought to the score his customary polish with his clear-toned baritone, and his ‘shopping list’ itemising the riches of Babylon was sung with emphatic relish. While the LSO provided deft and dancing support under Rattle’s vigorous baton, the performance never quite gripped as much as the music itself.

David Truslove

Gerald Finley (baritone), Sir Simon Rattle (conductor), Orfeó Català, Orfeó Català Youth Choir, London Symphony Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra

Royal Albert Hall, London; 20th August 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gerald%20Finley.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Prom 44: Sir Simon Rattle conducts Orfeó Català, Orfeó Català Youth Choir and the London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus product_by=A review by David Truslove product_id=Above: Gerald FinleyPhoto credit: BBC/Chris Christodoulou

Prom 45: Mississippi Goddam - A Homage to Nina Simone

The very title of this Prom, ‘Mississippi Goddam’, taken from Simone’s 1964 album, Nina Simone in Concert, comes from her first civil rights song and was written in response to the 1963 murder of Medgar Evers, and the September 1963 bombing of a Baptist church in Birmingham, Alabama. The song was controversial at the time - especially below the Mason-Dixon Line, where ‘Goddam’ was expunged and boxes of records sent to record stations were returned broken in half; but, despite its almost show-tune feel it remains extraordinarily powerful half a century later. The protest songs are one part of Simone’s output, but what this magnificent Prom also amply demonstrated is that Simone’s legacy and outreach is one of astonishing breadth.

In many ways, Simone was considerably more radical - and more complex - than other American artists of the time such as Ella Fitzgerald or Dina Washington. She was just very different to them; and the voice was too. If you were looking for a parallel today, the singer who most resembles her is Diamanda Galas: Both invoke the power of their feminist credentials, both cross into multiple musical genres, and both are unafraid to confront unfashionable and overtly political causes. Simone’s music can clash with her personal life, just as Galas’s does - when Simone writes and sings in ‘Be My Husband’ the slavery she is referring to is the abuse of marriage, but while it might be framed as a very personal story it has a universal truth to countless other American women trapped in abusive marriages. Galas’s Plague Mass isn’t just about her brother’s fight against AIDS - it’s an angry, terrifying onslaught against all personal AIDS battles.

Nina Simone’s voice was a lot of things, often within the same song. It could be extraordinarily warm, almost thickened like treacle, but also have an adenoidal range to it. It was unusually intense, even in her studio recordings for Philips or RCA, though some of her live performances on disc have a magnetism that is quite unique: ‘Dambala’, which appeared in 1974, and which was heard in this Prom, is staggering for its intensity and radiance. Improvisation mattered a great deal; but what is also there is what you can’t really teach. At her greatest, there is a depth and spirituality to the voice, a poetry and soulfulness which touches the visceral. In part this must certainly have much to do with Simone the inner woman: Fiery, volatile and prone to bouts of rage. Only later was she to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

It’s perhaps not surprising, given all this, that it took two singers to do justice to the songs in this concert. Ledisi and Lisa Fischer have strikingly different voices, in both colour and range. What they share is an ability to dig deep - if some of this concert was clearly a display of vocal virtuosity of the highest order, other parts of it were about exploring the plight of black women in America, their place in wider Eurocentric cultures or about how beauty and identity relate to women of colour. Fischer generally sang these more emotionally demanding songs; the smoky, dark soulfulness of her voice mostly caught the complex place of womanhood in a divisive cultural world. Fischer’s performance of ‘Dambala’ was simply profound, taken at such a slow tempo the power of it became unbearable. I’m not sure any song during the evening was more emotionally draining or invoked the sheer horror of slavery more successfully. The deliberate tempo, not to say the way in which Fischer drew us in, made us complicit in the hopelessness of ever unshackling those in slavery.

Ledisi and Jules Buckley. Photo credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Ledisi and Jules Buckley. Photo credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

This was a marked contrast to Ledisi’s performance of ‘I Put a Spell on You’ which had been almost cannibalistic - somewhat different to how Simone takes the song on her classic Philips recordings from 1964-5. Simone’s willingness to draw back from this song’s rawest elements, even to be restrained in it until winding up towards the end in typical belt-it-out fashion, isn’t a vision that Ledisi shares. From the very start, this was a performance that never shrunk from being a tour de force: If spells are remotely menacing this one wasn’t that, but it was simply naked with passion, inflamed with intensity and staggering in its vocal control. Predictably, it brought the house down.

From the same album on which ‘I Put a Spell on You’ appeared, Ledisi also sang ‘Ne me quitte pas’, one of the many songs which Simone wrote in French after she moved to Europe. Diction issues aside, this gave Ledisi an opportunity to bring some depth to her singing - which she did admirably. ‘My Baby Just cares for Me’ (from her very first album in 1958) was probably better sung by Fischer than by Simone herself. This is to all intents and purposes a love song, but Simone’s general unwillingness to embrace this genre (for a time she even forgot she had recorded this song) demonstrates a side of Simone’s character that could so easily interfere with her ability to communicate to audiences. Simone’s tendency to deflect her passions onto others, into feminism, enfranchisement and protest, masked an often loveless and abusive personal life, one in which she neither received nor gave much emotional feeling to others. If there’s a detached, almost matter-of-fact tenor to Simone’s version of this song Fischer sees it otherwise. ‘Plain Gold Ring’ (also from 1958) is almost callous when set beside this love song - a ballad of unrequited love, unfaithfulness and exploitation. Fischer, her credentials so woven into the mysteries of emotions and love, found herself equally at home in the complex triangulation of a love that would never be.

Fischer had also been the vocalist in two pieces which came from two very different operas - one of which Simone did sing and record, the other which she did not. Her musical range was, of course, eclectic - indeed, in her formative years she had intended to study at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia but was turned down, something which she spent the rest of the life insisting had been racially motivated. ‘I Loves You, Porgy’ from Act II of Gershwin’s opera (which she recorded in 1958) always showed Simone at her best: Tender, the voice at its most evocative and controlled. Fischer certainly had the range for it, if not quite the tenderness, but there was a feverishness to her singing which was entirely descriptive of the narrative. Much less successful - in fact a miss for me - was ‘Dido’s Lament’. Fischer’s somewhat quirky, rather gospel-inflected version of this was literally sectionalised into ups-and downs; at times it just sounded unsettling. The voice is unquestionably dark enough, it’s warm and tonally rich - I just couldn’t warm to this interpretation.

Lisa Fischer and Jules Buckley. Photo credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

Lisa Fischer and Jules Buckley. Photo credit: BBC/Mark Allan.

‘Mississippi Goddam’, sang so impeccably by Ledisi, was superb. Despite the protest elements of this song, its radical overtones, it is musically quite the opposite. Its jauntiness, elastic rhythms and incendiary beat cover a deeply invective narrative. Ledisi launched into it with an intensity that gripped one from the very beginning, but every word of this profoundly powerful song was sung from the heart. ‘Four Women’, from 1966, was sung by Ledisi, Fischer and two members of the backing group, LaSharVu. Although this song is about enslavement it is about something else: It is about identity, and especially how black women are stereotyped. Unquestionably, the version of the song here probably worked better than Simone’s own because the sense of identity shared by different women was better advocated for, by voices which were very different in colour themselves. There was a deep spiritualism to this song in this performance - but also a contrast to the African-American, or mixed-race stereotypes which so inspired Simone to write it in the first place.