September 27, 2019

Handel's Aci, Galatea e Polifemo: laBarocca at Wigmore Hall

But, this wasn’t the first time that Handel had turned his attention to the Ovidian love-triangle between the mortal shepherd Acis, the sea-nymph Galatea and the Cyclops Polyphemus who, in a jealous rage, kills Acis, prompting Galatea to transform her beloved into an immortal river spirit. The allegorical tale was also the subject of the 1708 serenata Aci, Galatea e Polifemo which Handel composed in Naples in 1708 for Aurora Sanseverino, Duchess d’Laurenzana as a wedding gift for her nephew, Duke Tolomeo d’Alvito.

The intimate, decorous Wigmore Hall was a fitting setting for this performance by Roberta Mameli, Sonia Prina and Luigi De Donato with the Italian Baroque specialist ensemble, laBarocca, conducted by Ruben Jais. Founded in Milan in 2008, the sixteen-piece ensemble play with a light-textured vitality which here enhanced the delicacy and economy of many of Handel’s aria accompaniments, some of which employ continuo alone while others develop beautifully expressive duets between the solo voices and obbligato instruments. Jais decreed a prevailing gentleness which could then be dramatically enlivened by striking dynamic contrasts, occasional gritty textures and instrumental colour.

Handel’s serenata reveals not only the young composer’s confident appreciation of the requirements and expectations of the form, but also the considerable skill with which he could characterise in music. The role of the male lover, Aci, was written for a soprano castrato, as was the convention, with Galatea performed by a lower female voice. Here Roberta Mameli’s light, bright soprano was perfectly complemented by Sonia Prina’s dark, dense but pliable contralto. In their opening duet - which followed segue from an interpolated Sinfonia (Handel’s score provides no instrumental prelude) - Mameli’s brightness and ‘lift’ captured Aci’s optimism and joy as the day breaks and a serene sky seems to promise the lovers future joy, while Prina thoughtfully supported the higher line, shaping the phrases sensitively to convey Galatea’s passion.

Mameli and oboist Nicola Barbagli intertwined and echoed sublimely in ‘Che non può la gelosia’, their silky running triplets in thirds communicating the shepherd’s unrest when he first learns of Polifemo’s jealousy, strengthened by some thumbing bass line accents. When Aci prepares himself to do battle with the Cyclops, Handel surprising scores his aria for ‘solo cembalo’, even though librettist Nicola Guiva has supplied him with images of eagles’ talons ripping into a snake’s nest inspiring violent and venomous vengeance in the latter. Perhaps he wished us to foreground such imagery without distraction? Here, Jais employed the harpsichord alone but, as Mameli projected forcefully (sometimes a little too much so, with adverse effect on the intonation) the relationship between the voice and the rather fragile, rapid harpsichord part became loosened.

Roberta Mameli (soprano). Image courtesy of Allegorica opera management.

Roberta Mameli (soprano). Image courtesy of Allegorica opera management.

More successful, and considerably moving, was ‘Qui l’augel da pianta in pianta’ in which Aci reflects first on the carefree carolling of the birds which charms his heart, and then on the contrast between the birds’ happiness and his own grief. The preceding recitative closed with transfiguring gentleness as Aci asks the stars to allow him one more chance to gaze upon his beloved, whereupon he will die content. A weighty silence interposed before Barbagli’s oboe began its sweet song, inviting the shepherd to join in and charm his languishing heart. Here, Mameli employed a tender piano with affecting power and displayed superb accuracy in her avian lilting and trilling. The strings of laBarocca provided a bed of barely there tenderness for Aci’s final anguished ‘Verso già l’alma’, the harmonies softly and subtly altering, communicating the twists of grief in Aci’s heart as Mameli blanched her soprano to the merest, iciest thread.

I have more frequently heard Sonia Prina in roles which require her to rant and rage, which she does with dramatic potency and energy but with occasional mishaps as she leaps between registers and vents unbridled passion and anger. As Galatea she was able to display the more composed emotional depths which her rich contralto, with its velvety bottom and richly focused top, can convey. There was a lovely delicacy when the sea-nymph first tells Aci of the suffering that he must forebear, though strong resentment in the recitative in which she reveals Polifemo’s wrath and cruelty. The fury increased when Prina, arms crossed in indignation, launched into an agile ‘Benché tuoni e l’etra vvampi’ in which Galatea, allied with the oboe, envisions herself as a laurel tree, standing steadfast again the thunder’s fiery flashes as evoked by the dry spiky semiquavers of the strings. Surely few thunder gods would dare to challenge the steely insistence of Galatea’s closing avowal of invincibility, which Prina sustained long and darkly, while her final battle with Polifemo bristled with aggrieved energy and fury.

Luigi De Donato (bass). Image courtesy of Allegorica opera management.

Luigi De Donato (bass). Image courtesy of Allegorica opera management.

Heralded by a strident fanfare from trumpets and oboe, as Polifemo Luigi De Donato found a good balance between vocal refinement and the Cyclops’ crude clumsiness. De Donato’s diction was excellent, in the recitatives especially, where he used his firm and centre bass to bring the words to life. In his first aria, ‘Se schernito son io’, Polifemo may have been trembling with anger but the bass’s delivery was as authoritative as De Donato’s tall, imposing stance. ‘Fra l’ombra e gli orrori’ caught us unawares with its dark dignity, as Polifemo laments his loss once Galatea has thrown herself in the waves forever. De Donato cleanly negotiated the repeated, challenging leaps in the vocal line, with tight trills in the bass and muted strings signalling his heart-churning distress. The Cyclops has the last word of the drama, and Polifemo’s accompanied recitative of repentance was beautifully hushed.

Aci, Galatea e Polifemo possesses little of the mirth of Handel’s subsequent myth-telling mini-opera and - surprisingly for a work intended to be performed at a nuptial celebration - the tone becomes progressively more sombre and even severe. Jais was not entirely successful in sustaining momentum during a series of subdued and solemn numbers, and perhaps could have looked for greater emotional contrast.

The sudden shift at the close to the brisk moralising chorus was rather destabilising, the characters whom we have been encouraged to empathise briskly shedding their dramatic robes and revealing themselves as personified moral symbols in a philosophical debate. But, if the gruesome end which sees Aci felled by a boulder seemed inapt to the Neapolitan weddings guests in 1708 then they must have been reassured by the final confirmation: “Who loves well has aims of faithful love and pure constancy.”

A few patrons left the Hall before the close, perhaps not anticipating that a performance scheduled to last 90 minutes would over-run by almost a third. But, those who remained offered full-voiced praise to the singers and musicians for a performance that offered dramatic dignity and musical delights.

Claire Seymour

Handel: Aci, Galatea e Polifemo HWV7

Aci - Roberta Mameli (soprano), Galatea - Sonia Prina (contralto), Polifemo - Luigi De Donato (bass), Conductor - Ruben Jais, laBarocca

Wigmore Hall, London; Thursday 26th September 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Sonia%20Prina%20%40Javier%20Teatro%20Real.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Aci, Galatea e Polifemo: laBarocca, Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Sonia Prina (contralto)Photo credit: Javier Teatro Real

Gerald Barry's The Intelligence Park at the ROH's Linbury Theatre

Currently showing at the Museum is a fantastic special exhibition, Two Last Nights! Show Business in Georgian Britain, which opens a window on the often riotous and raucous goings-on both front-of-house and behind-the-scenes in the eighteenth-century theatre and opera house, through exhibits such as fans printed with seating-plans to show where the great and good could be found, large illustrated tickets which are works of art in themselves, sharp contemporary cartoons and over-crowded playbills.

The latter are astonishing, showing the extent and diversity of the variety and vaudeville, sketches and song on offer each long evening of entertainment. A similar bill in the Burney Collection at the British Library gives the flavour: at the King’s Street Theatre in Bristol on the evening of 23rd August 1775, theatre-goers could enjoy Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer, before which they were treated to a Prelude written by one George Colman Esq., while the play was followed by a ‘New Dance to which will be added A New Dramatic Entertainment, The Maid of the Oaks’, concluding with a Fête champêtre - illuminated with ‘near one thousand lamps’ original songs and choruses, a new minuet. The whole evening concluding with a dance. Preludes and after-pieces, divertissements and dances, comedies, dramatic romances, tragedies and farce frequently collided. Not surprising, Hogarth’s pen skewered both the artistes and the players, the aristocrats and the plebs.

I justify this rather diversionary preamble to my review of Music Theatre Wales’ production of The Intelligence Park at the ROH’s Linbury Theatre because Gerald Barry’s first opera resembles such a marathon Baroque bombardment. Both Hogarth and Handel, the latter whom Barry professes to admire, were fervent supporters of the Foundling Hospital Chapel - from 1749 Handel gave an annual benefit concert, raising thousands of pounds for the Hospital - and Barry channels Hogarth in his metatheatrical mash-up, though with little of the neoclassical wit and precision, tempered by soul-touching lyrical sentiment, that Stravinsky demonstrates in The Rake’s Progress. Instead Barry wields an iconoclastic sledgehammer, bludgeoning all connections between sound and syntax that might provide structural and semantic coherence … or, at least a semblance of comprehensibility.

Michel de Souza as Paradies, Adrian Dwyer as D'Esperaudieu Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Michel de Souza as Paradies, Adrian Dwyer as D'Esperaudieu Photo credit: Clive Barda.

But, then, Barry’s not in the business of ‘coherence’. In the sleeve notes to the 2005 NMC recording of the first production of The Intelligence Park at the Almeida Theatre in July 1991 (which was broadcast on BBC Radio 3), Barry professes not to like ‘texts which are bound by logic or plot’, preferring instead those, such as that by his librettist Vincent Deane, characterised by ‘coolness and a bizarre artificiality which allow extreme careering at tangents’.

In fact, the essential plot and the ‘opera-about-opera’ paradigm of The Intelligence Park are pretty straightforward, it’s the idiom and execution which scramble reason and rationality. The time is 1753, the place Dublin. Robert Paradies has composer’s block and is struggling to complete his new opera. Marriage to his fiancée, Jerusha Cramer, will bring him her bombastic father’s money, and the leisure to devote himself to his art. But, he’s obsessed with the castrato Serafino, who is Jerusha’s singing teacher. Worse still teacher and pupil elope. The plus side is that Paradies infatuation fuels his musical inspiration; the downside is that Serafino and Jerusha transmute into Wattle and Daub who find their way into his opera. As real and imagined become inextricably tied up in creative and romantic knots, Paradies loses his grip.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

As a metareferential document of a creative crisis, The Intelligence Park is not, in theory, so different from Franz Schreker’s penultimate opera,Christophorus oder ‘Die Vision einer Oper’ ( St Christopher, or ‘The Vision of an Opera, 1924-29). Barry, though, sets out to destroy any conduit through which intelligibility might be communicated. The vocal lines deliberate disrupt syntax and meaning, through rhythmic fracture, elongation and hysterical stuttering, and through melodic and registral displacement and athletic angularity. The singers are required to essay vocal gymnastics, with the male roles leaping between falsetto and Hadean depths. If the word-setting is not so much arbitrary as deliberately anarchic, then the prevailing fortissimo wind-brass dominated accompaniment of punching patterns of repetitive staccatos obliterates the text in any case. In the Linbury Theatre I could detect scarcely a word of Deane’s 18th-century linguistic style-games, which are themselves intercut with splashes of Italian, and was forced to choose between gazing up at the oh-so-high surtitles to learn what was being said or looking at the stage itself to try to work out what was going on. Neither course of action produced a satisfying result.

Adrian Dwyer as D'Esperaudieu, Stephen Richardson as Sir Joshua Cramer, Stephanie Marshall as Faranesi. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Adrian Dwyer as D'Esperaudieu, Stephen Richardson as Sir Joshua Cramer, Stephanie Marshall as Faranesi. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

There is no danger of music and words coming together in any ‘meaningful’ relationship; indeed, they are surely designed to be in combat. Each theatrical element does battle with every other aspect of the ‘drama’ and the result is a frenetic but self-consuming energy which burns itself to obliteration on a bonfire of the bizarre. Director-designer Nigel Lowery’s toy theatre-style painted sets are imaginative and eye-catching. But Lowery substitutes excess for elucidation: smeared clown make-up, outsize Aristophanic head masks, manic stage business - all seems designed to obscure rather than to explicate.

Rhian Lois as Jerusha Cramer Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rhian Lois as Jerusha Cramer Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The cast, however, give their all. It was announced at the start that Michel de Souza was unwell, and surely by the end he must have felt truly dreadful having been asked to force his voice high and low, and generally swallow and strangle sound and syllable. As he companion D’Esperaudieu, Adrian Dwyer was more successful than most in communicating if not meaning then at least words, and he and Rhian Lois as Jerusha were able to produce a focused tone which could carry about the tumult and communicate with some directness. Not so Patrick Terry, as Serafino, who, despite a characteristically committed and game performance was often inaudible. Stephen Richardson threw himself about the stage and his voice in all directions as Sir Joseph Cramer; Stephanie Marshall completed the dedicated cast. Raphael Flutter’s solo treble was transmitted in recorded form via the bobbing heads of the grotesque putti slouching on the columns of the theatre-within-a-theatre set. Conductor Jessica Cottis guided the London Sinfonietta confidently but when she joined the cast on stage for the curtain-call she looked exhausted, only tentatively allowing herself what seemed a relieved smile.

Patrick Terry as Serafino. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Patrick Terry as Serafino. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Paradies’ opera audience - who prefer card games and gastronomic cuisine to genuine ‘culture’ - formed a row of rubbery double-headed Francis Bacon-inspired Dummies: I guess this was ‘us’. But, if The Intelligence Park is an opera about unfulfilled creativity, then I wondered just whose creativity was under the spotlight. Some commentators have described Barry as a ‘visionary’. I found his fantastic, frantic pastiche tedious: thinking of Birtwistle’s Punch and Judy, or imagining what Adès might do with this conceit, made it hard to discern just what ‘vision’ it was that Barry was supposed to have had.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Admittedly, I was no fan of the composer’s 2011 opera The Importance of Being Earnest , which won widespread acclaim, but in that case Wilde’s perfectly well-made play was able to withstand Barry’s rough treatment. On this occasion, I began to wish that the Grim Reaper who haunted the production with increasing frequency would wield his scythe on proceedings. That said, there were plenty in the Linbury who voiced their praise vigorously at the close. Visionary or Emperor-with-no-clothes?

Claire Seymour

Gerald Barry: The Intelligence Park (Libretto: Vincent Deane)

Robert Paradies - Michel de Souza, D'Esperaudieu - Adrian Dwyer, Sir Joshua Cramer - Stephen Richardson, Jerusha Cramer - Rhian Lois, Serafino - Patrick Terry, Faranesi - Stephanie Marshall; Director and Designer - Nigel Lowery, Conductor - Jessica Cottis, Lighting assistant - Fridthjofur Thorsteinsson, London Sinfonietta

Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House, London; Wednesday 25th September 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/The%20Intelligence%20Park.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Gerald Barry’s The Intelligence Park: Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Photo credit: Clive BardaAn interview with Cheryl Frances-Hoad, Oxford Lieder Festival's first Associate Composer

Jeanette Winterson’s words, from her 1993 novelWritten on the Body, would make a good epigraph for this year’s Oxford Lieder Festival. In recent years the Festival has shone a spotlight variously on Schubert’s entire song oeuvre, ‘Poets and their Songs’, and Gustav Mahler and fin-de-siècle Vienna. Last year the Festival undertook a ‘Grand Tour’ - a European journey in song, which explored cultural influences from Finland to the south of Spain, from Dublin to Moscow.

Next month, the Festival’s focus will be storytelling. Tales of Beyond - Magic, Myths and Mortals will comprise a multitude of narratives, mischievous, magical and musical. In fact, one might argue that all music-making is about telling a story, whether it takes the form of a song setting a single poem, the development of a drama in a symphony or opera, or the conversational interplay of chamber music. Music’s ‘meaning’ may be ultimately ineffable, from ‘beyond’, but there’s no doubt that it ‘speaks’ to us, communicating the real and the imagined, directly and ‘magically’.

The 2019 Festival also marks the start of Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s three-year appointment as Oxford Lieder’s first Associate Composer. “It’s phenomenal,” says Cheryl, when I meet with her to discuss her new role. “To have the position for one year would be fantastic, but three years is incredible.” Cheryl explains how her association with the Festival’s founder and Artistic Director, Sholto Kynoch, has developed. In 2011, as a member of the Phoenix Piano Trio, pianist Kynoch and his fellow musicians premiered Cheryl’s The Forgiveness Machine , which the Trio had commissioned as part of their Beyond Beethoven project. Subsequently they recorded the work on Stolen Rhythm , a disc of Cheryl’s music for the Champs Hill label. In 2016, Oxford Lieder commissioned The Thought Machine , a new song-cycle for performance at a concert for children. An Arts Council grant enabled Cheryl to develop the piece into a participatory work involving music, poetry and hand shadows, working with singer-pianist ensemble Songspiel and hand shadowgrapher Drew Colby who have toured The Thought Machine to schools in Peterborough and Cambridge and will bring it back to this year’s OLF.

As Associate Composer, Cheryl’s music will be heard frequently during the next three Oxford Lieder Festivals. Each year a new work will be commissioned. This year, Cheryl’s setting of Baudelaire’s ‘Une Charogne’ will be included in a programme of French Fables performed by contralto Jess Dandy and Sholto Kynoch, while in 2020 a new 20-minute work for soprano and piano will be premiered, with a longer 45-minute composition following in 2021. It’s an ambitious, extended project for Oxford Lieder. Cheryl suggests that since the Festival was founded in 2002, a strong relationship between the large, regular audience and the Festival has developed, in ways that have allowed for increasingly more adventurous programming.

Marta Fontanals-Simmons Photo credit: Victoria Cadisch.

Marta Fontanals-Simmons Photo credit: Victoria Cadisch.

Thus, this year’s Festival will also include new works by other composers. Mezzo-soprano Kitty Whatley and pianist Simon Lepper will perform Juliana Hall’s ‘monodrama’ Godiva, which sets a libretto by Caitlin Vincent, in a programme of Fairy Tales from Stanford to Sondheim. The following evening sees the world premiere of Martin Suckling’sThe Tuning , a song-cycle setting the poetry of Michael Donaghy, by mezzo-soprano Marta Fontanals-Simmons and pianist Christopher Glynn, in a recital which also includes a performance of Schubert’s Die schone Müllerin by baritone Roderick Williams.

‘Une Charogne’ posed a new challenge for Cheryl as it was the first time that she had set a French text. She explains that she was grateful for the help and advice offered by Helen Abbott, Professor of Modern Languages at Birmingham University, who has a special research interest in nineteenth-century French poetry and music, and who, during the 2018 OLF presented a collaborative coaching masterclass day for singer/pianist duos focusing on French song, especially Verlaine/Debussy.

Helen’s current research project is the Baudelaire Song Project . She helped Cheryl - whose last experience of reading and speaking the language was during her GCSE French studies! - with Baudelaire’s text, explaining matters such as pronunciation, how to divide the syllables of a word and the correct text layout on the score. She also made recordings of the poem, at both a slow and normal speaking speed. In addition to studying a translation of the poem, Cheryl also translated each individual word herself; before she began her musical setting, she could speak the text fluently.

Jess Dandy. Image courtesy of the Oxford Lieder Festival.

Jess Dandy. Image courtesy of the Oxford Lieder Festival.

Taken from Baudelaire’s Fleur du mal, ‘Une charogne’ is a startling, almost Goya-esque, memento mori in words. The eponymous carcass inspires incongruous images, and as themes of love and life, death and horror weave together, the beautiful and grotesque collide. Alternating Alexandrine and octosyllabic lines create a natural ebb-and-flow, and individual sounds enhance the ‘musicality’ of the poem. But, I ask Cheryl, how on earth does one go about finding musical imagery to embody phrases such as, “The blowflies were buzzing round that putrid belly,/ From which came forth black battalions/ Of maggots, which oozed out like a heavy liquid” (Les mouches bourdonnaient sure ce ventre putride,/ D’où sortaient de noirs bataillons/ De larves, qui coulaient comme un épais liquide)? A glance at the score suggests that Cheryl hasn’t been averse to some literal word-painting at times - there’s a very busy, decorative right-hand line at the point of the aforementioned image of decay - but her setting seeks to present the poem’s incongruities in a more holistic way, and to capture equally the poem’s bizarre humour, ecstatic reveries and its graver intimations of distortion, dissolution and decay.

A second composition by Cheryl will have its world premiere during the OLF, though it was not specifically commissioned by the Festival. Endless Forms Most Beautiful , a song-cycle for soprano and string quartet, will be performed in Oxford’s Museum of Natural History by soprano Carola Darwin and the Gildas Quartet. In 2000, Cheryl met Carola, who is Charles Darwin’s great-great-granddaughter, when she took part in a competition run by the Darwin Centre at the Natural History Museum. “I didn’t win,” Cheryl smiles, “but I did become friends with Carola” and the idea of a cycle of songs setting texts about the environment and evolution was borne. 19 years later, it has come to fruition.

Endless Forms Most Beautiful takes its title from Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species:

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

Gildas Quartet. Image courtesy of the Oxford Lieder Festival.

Gildas Quartet. Image courtesy of the Oxford Lieder Festival.

Its seven songs set texts by the 19th-century poet Walter Deverell (‘The Garden’) and the NHM’s three 2016 Poets-in-Residence: Kelley Swain (‘To the Paleontologists’, ‘Cetacean Introduction’, ‘Bones’, ‘Thermodynamics of Immortality’), John Barnie (‘Let’s Do It’) and Steven Matthews (‘Yet With Time’s Cycles Forests Swell’). I ask Cheryl how she went about selecting the texts. “We chose poems that we liked and that fitted the theme. At that stage I didn’t pay much attention to potential issue relating to text-setting, and in fact some of the poems are quite long and in some places I have cut some text.” Do they present an unfolding ‘narrative’? “Not really, they do all relate to the general theme but could be performed as individual songs.”

During the next three years, OLF will present all of Cheryl’s existing songs, as well as selected chamber music, and piano and choral works. Next month, Jess Dandy and Dylan Perez will performBeowulf, Cheryl’s 2010 setting of extracts from Seamus Heaney’s translation of the Old English epic. Pianist Ivana Gavrić will play four of Cheryl’s piano works in a concert including works by Clara Schumann and Edvard Grieg, and the Choir of Merton College will sing Bogoroditse Dyevo which was composed as part of a project to create six new works, by six different composers, each of which was inspired by an earlier work, and for which Cheryl drew upon Rachmaninov’s well-known Vespers.

Cheryl’s works include a Piano Concerto, Cello Concerto, several large-scale works involving young musicians and much chamber music, but she has perhaps been most widely acclaimed as a composer of songs and other vocal works. I ask her if she feels a particular predilection for working with words, and she admits that she does find that working with a text makes composition ‘easier’ to some extent. Her oeuvre is extensive, and her music is frequently performed. However, Cheryl feels that she is reaching a point in her career where she would like to make some space and time to reflect on her longer-term plans. “During the last 10 years I’ve enjoyed being able to compose many works ‘for my friends’, but now I’d like to ask myself, ‘what do I want to write?’,” she laughs. Might she also want to expand her canvas? Three choral works will be her immediate compositional focus but after that … perhaps an opera, and other larger works? She hints at some forthcoming projects, which will present fresh and exciting challenges.

The 2019 Oxford Lieder Festival runs from 11-26 October. Claire Seymour image=http://www.operatoday.com/Frances-Hoad%2C%20Cheryl%20title.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title= product_by=An interview by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Cheryl Frances-HoadSeptember 24, 2019

O19’s Phat Philly Phantasy

Sergei Prokofiev’s score crackles with colorful effects all evening long, and when it on occasion modulates to more lyric leanings, the tunes are marked by a pleasant melancholy. There are bursts of joyous abandon as well, like the Prince’s laughing fit, a cackling drag act, and the eventual wedding celebration. The main intent of the somewhat convoluted story is to entertain, and entertain it does. And how!

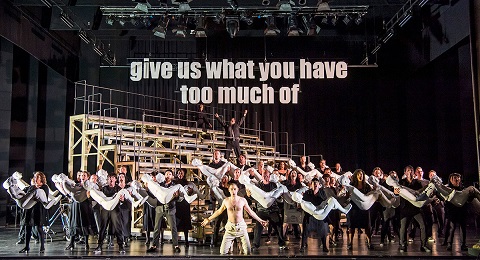

From the time we enter the auditorium, we can see a stage within a stage as designed by Justin Arienti, whose large white, ornate false proscenium is set well back from the apron, and is not masked by legs, so we see the actual walls and stage machinery “off-stage.” A pair of tall scaffolds flank the real proscenium right and left.

At the downbeat, boisterous gangs of men advocate the interests of Tragedy, Comedy, Lyric Drama and Farce. They are subsequently herded to populate the various levels of the downstage towers, and are told that there will be something for everyone in the show that they are about to witness, called: The Love for Three Oranges. Elizabeth Braden’s chorus was once again flawless in their accomplishment.

Director Alessandro Talevi keeps things percolating, and his unerring sense of restless, intricate group movement could qualify him as an air traffic controller at Philadelphia International. Mr. Talevi’s vision not only keeps the action moving, but also knowingly deploys an admirable sense of focus, so we are always directed to the important moment at hand. His admirable skill at crowd control is exceeded only by his ability to craft witty business between individual characters in well-realized chamber scenes.

Just as designer Arient has a few tricks up his sleeve with scenic effects (shadow play, mechanized rat, etc.), Manuel Pedretti’s over-the-top costumes engage the eye, and define the diverse dramatic personalities. His cheeky interpretation of the Cook as a bloated chicken (no kidding) is inspired lunacy. The uber-talented David Zimmerman outdid himself with an inspired wig and make-up design that knew no bounds for fantasy and invention. Giuseppe Calabrò’s ever-morphing, malleable lighting design made sure that all of the other technical elements were beautifully showcased to maximum advantage, by shifting the mood and underscoring the dramatic intent with effortless skill.

It would be difficult to overpraise the incisive, magical reading that Corrado Rovaris elicited from the pit.The Maestro has helmed a shimmering, capricious reading of the composer’s ebullient score that enchants the ear, tickles the senses, and warms the soul. Whether playing as a tightly focused ensemble or featuring characterful solos, this accomplished band responded with a reading that is one part effervescence, one part meticulous stylistic realization, and 100 per cent magnificently reverberating accomplishment.

The large cast of soloists is evenly matched, and meticulously cast. As the melancholy Prince, the slender and youthful Jonathan Johnson strikes just the right balance of pouting charm and hang dog demeanor. Mr. Johnson’s freely produced, gleaming tenor fills the house with ease, thanks to his well-focused delivery. He makes the famous laughing scene irresistibly infectious, and he subsequently morphs into a character of determined maturity.

As his sidekick Truffaldino, Barry Banks’ pliable tenor soared fearlessly, effortlessly to encompass the heights demanded by this role’s tessitura. Mr. Banks’ loose-limbed presence animated his every scene, and we rather missed him when he was off stage. He also deftly voiced the gentle tragedy as he unwittingly causes the death of two princesses.

Scott Conner was a solid, sure-voiced King of Clubs, his impressively rolling bass possessed of just the right amount of bite to project the regal frustration that informs the character. Wendy Bryn Harmer was a powerful presence as a plush-voiced, potent Fata Morgana. Ms. Harmer admirably deployed her substantial, warmly tinged soprano with gleefully wicked coloring.

As the plotting duo Princess Clarissa and Leander, Allissa Anderson and Zachary Altman oozed mellifluous malintent. Ms. Anderson’s generous, throbbing mezzo made the most of her every utterance, while Mr. Altman’s oily, unctuous vocal delivery was informed by a handsome, commanding bass baritone of considerable stature.

Bass Zachary James’ towering physical presence is exceeded only by his towering talent on ample display in the featured role of The Cook. This outrageous drag act not only makes Mr. James a female, but as noted above, actually makes him a chicken. No chicken (s)he when it comes to hurling out musical phrases that throb with theatrical urgency and refulgent vocalizing. His coy girlish playfulness obtaining the ribbon he covets was alone worth the price of admission.

Tiffany Townsend was a ravishing vocal presence as the (surviving) Princess Ninetta. Ms. Townsend’s lustrous, creamy tone has spinto leanings, and her instrument sounds wondrously even and ravishing at all volumes and in all registers. This young talent is certainly a singer to watch as her star is sure to rise. Her sister Princesses Linetta and Nicoletta, were well-served by two assured mezzos, the former showcasing Katherine Pracht’s shining presentation and the latter wonderfully illuminated by Kendra Broom’s meaty, yet melting tone.

Even the smallest of cameos is cast from strength, a testament to the total achievement of the casting director. Brent Michael Smith’s strong delivery and admirable bass made the most of Chelio’s statements. Mezzo Amanda Lynn Bottoms’ poised, utterly secure phrases made a good case for Morgana’s treacherous accomplice Smeraldina. Will Liverman’s suave, elegant baritone is luxury casting for the King’s advisor Pantaloon. Ben Wager’s plucky bass enlivened the demon Farfarello; tenor Corey Don Bonar was the successful Master of Ceremonies; and bass Frank Mitchell richly intoned the pronouncements of the Herald.

Orange(s) is the new . . .hit. This winning mounting of The Love for Three Oranges should inspire other American companies to follow suit, especially those with the depth of Young Artist programs, and bring this inventive composition to a much wider audience. Bravi tutti to the wide-ranging participants that winningly brought Prokofiev’s unique creation to unforgettable life on the Academy stage.

James Sohre

The Love for Three Oranges:

Music - Sergei Prokofiev

Libretto - Sergei Prokofiev and Vera Janacopoulos

The King of Clubs: Scott Conner; The Prince: Jonathan Johnson; Truffaldino: Barry Banks; Fata Morgana: Wendy Bryn Harmer; Princess Clarissa: Alissa Anderson; Leander: Zachary Altman; Chelio: Brent Michael Smith; Ninetta: Tiffany Townsend; The Cook: Zachary James; Smeraldina: Amanda Lynn Bottoms; Pantaloon: Will Liverman; Linetta: Katherine Pracht; Nicoletta: Kendra Broom; Farfarello: Ben Wager; Herald: Frank Mitchell; Master of Ceremonies: Corey Don Bonar; Conductor: Corrado Rovaris; Director: Alessandro Talevi: Set Design: Justin Arienti; Costume Design: Manuel Pedretti; Lighting Design: Giuseppe Calabrò; Action Design: Ran Arthur Braun; Wig and Make-up Design: David Zimmerman; Chorus Master: Elizabeth Braden

image=http://www.operatoday.com/oranges-22.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Opera Philadelphia: The Love for Three Oranges

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=All images © Kelly & Massa

Agrippina: Barrie Kosky brings farce and frolics to the ROH

In Vincenzo Grimani’s libretto for Handel’s Agrippina, this inveterate liar, intriguer and practiced murderess has a single aim - the usurpation of her husband Claudius’s throne by her son, Nerone. The Venetian Grimani, a nobleman and cardinal, knew a thing or two about reaching the top, whether via diplomacy or duplicity: his career culminated in his appointment as Viceroy of Naples in 1708. Not long afterwards, in December 1709, his vicious satire depicting ruthless intrigues in ancient Rome motivated by vengeance and sexual gratification was enticing the punters at the Teatro Grimani di S. Giovanni Grisostomo in Venice. Agrippina ran for 27 performances, until February 1710: it was the 25-year-old composer’s first operatic triumph.

Some of Grimani’s cast of licentious liars had featured in Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea, 70 years earlier, in a more subtly comic dramatic context. Barrie Kosky’s production of Handel’s opera - seen first in Munich earlier this summer - ignores the fact that the Handel-Grimani take on these power-sex conspiracies might be rather more than ‘just comic’, and strives to turn proceedings into a Roman sit-com, with pairs of loathsome criss-crossing lovers and colluding connivers coming a cropper. There is, as always, both irony and pathos in Handel’s score, but Kosky puts his money on frenetic farce.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Rebecca Ringst’s steel box-frame design offers plentiful stairways, corridors, blinds and inner chambers for eavesdroppers to find hideaways and intriguers to conspire. As the plottings unfold, the box swivels and dismantles, its moving parts emblematic of the human chess game being played by Agrippina. It’s no surprise that at the height of the hugger-muggering - when, at the opening of act 3, a trio of Romans visit Poppea’s apartments, lured by her panto-esque ploy of hide-and-hear - Joachim Klein’s eye-burning lighting of the white-on-white interior renders the audience as blind as the protagonists. Nor, that the Meccano-parts are reassembled when Agrippina checkmates one and all.

Grimani’s libretto is one of the most psychologically and dramatically convincing that Handel set, and even though Agrippina has a high proportion of self-borrowed material (some scholars have suggested that as many as 50 of the 55 separate numbers have known precursors), Handel’s score is compelling, inspired by youthful creativity, confidence and vigour. The recitatives are lengthy but persuasive, often bringing voices together in ways which drive the drama onwards. In the ROH pit, conductor Maxim Emelyanychev pushed the pace and challenged the singers to keep up: the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment were impelled by the innate harmonic energy and a driving and robust bass line. The continuo timbres were varied and alert, and the oboe players deserved a bonus.

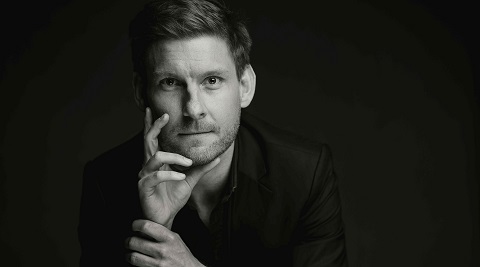

Iestyn Davies as Ottone. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Iestyn Davies as Ottone. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

So why, given too that there was some splendid singing to enjoy, did I feel slightly dissatisfied? I think it’s because Kosky seems not to appreciate Handelian irony. Grimani provides copious intrigue and irony. Handel enhances this by composing music which is often at odds with the apparent sentiments of the text. So, when in Act 1 the words of Agrippina’s ‘Non ho cor che per amarti’ seem to assure Poppea that Agrippina is her BFF, the minor key and sinuous melodic lines tell us otherwise. There is no need for theatrical signposting. Time and again I found myself reflecting on a Shakespearian parallel: that if Iago does not indeed seem ‘honest’ to the other characters, then the dramatic credibility is destroyed - whatever audience collusion is generated by Iago’s play-dominating soliloquies. In Kosky’s production there is far too much minxing, mincing and melodramatising. He doesn’t trust Handel to do the work for him.

Fortunately, Kosky has a fine cast to present his petulant playground antics. Ever a theatrical animal, Joyce DiDonato relishes the extroversion and exaggeration of Kosky’s conception of Agrippina, which seems to owe much to American 1980s TV dramas Dynasty and Dallas. DiDonato pushes her voice hard in Act 1, but doesn’t really delve into the emotional depths of Act 2’s ‘Pensieri, voi mi tormentate’. With the follow-spot shining, she wields a diamante-studded microphone with aplomb - when Agrippina morphs into a Judy Garland clone (why?) - but it’s not until the closing moments, when she claims that it was love for Claudio that led her to secure the throne for Nerone, that the musical simplicity and sincerity of ‘Se vuoi pace’ allows DiDonato - without Kosky’s interference - to fulfil Handel’s deliciously ironic directness.

As Poppea, Lucy Crowe flounces and flirts hyperactively. If she’s not ‘doing a Marilyn Monroe’ on the steel staircase, then she’s fluttering her skirts and flashing her knickers - this Poppea’s self-love outweighs her suitors’ adoration! Not that Crowe doesn’t produce the vocal goods to justify such adulation: Emelyanychev pushed her rather too fast in ‘Se giunge un dispetto’ and after some dizzying coloratura the climatic phrase-peaks rather lost touch with their harmonic roots, but Crowe demonstrated fine breath control and rhythmic clarity.

Gianluca Buratto as Claudio, Lucy Crowe as Poppea. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Gianluca Buratto as Claudio, Lucy Crowe as Poppea. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

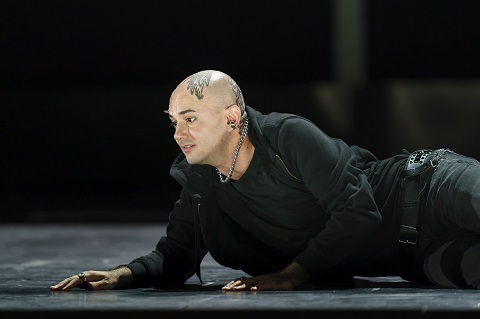

The first-night audience went wild for Franco Fagioli’s tattoo-headed, eyebrow-studded, hoodie-slouching Nerone. I was less enamoured. Handel wrote the roles of Nerone and the courtier Narciso for castrates; Fagioli sings with a nerve-twitchingly wide vibrato and his tone is piercing rather than ingratiating; he gets around the coloratura but in a rather mechanical, rather than meaningful, way. I don’t think that this role needs to be sung by a woman: one can imagine a rich feminine voice, such as that of Philippe Jaroussky, serving the role well, and offering rather more complex characterisation than Fagioli’s pouting, wall-pounding, floor-stamping adolescent. Nerone’s final aria, ‘Come nube che fugge dal vento’, in which he claims that he has broken the enchantment of his infatuation for Poppea, did however suggest that Fagioli might have had more to say than Kosky allowed.

Franco Fagioli as Nerone. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Franco Fagioli as Nerone. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Gianluca Burrato was dramatically convincing as Claudio, prepared to look a fool with his trousers round his ankles, but his lower register was not entirely secure or firm. As Agrippina’s would-be suitors Pallante and Narciso, Andrea Mastroni and Eric Jurenas’s comic antics didn’t make much of a mark, though there was little to fault with their singing; the same could be said for José Coca Loza’s Lesbo, Claudio’s ‘Leporello’.

Iestyn Davies as Ottone was alone in his appreciation of the sincere characterisation embodied in Handel’s music and text-setting. When he appeared before the Imperial palace, expectant of glory in acknowledgement of his heroic deeds, this Ottone seemed genuinely unaware that he is about to be denounced as a traitor. Having been assaulted violently with a lead pipe, he delivered the dissonant recitative and expressively eloquent ‘Voi, che udite’ with a musical precision and psychological perspicacity which was unique during this evening’s performance.

It was only at the very close of the opera that Kosky approached anything like this sort of veracity. The director eschews Juno’s divine intervention and offers instead a slow oboe-led movement from L'Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato. Agrippina retreats to the steel-box and takes a seat, alone … victorious? Nero is Emperor: she’s won, hasn’t she? Tantalisingly, in these final moments Kosky shows that he understands the inherent tragedy that Handel ironically unfolds … the moment is a bit too late to really make its mark, but it’s welcome. As today’s politicians are realising, as events unfold, the winner doesn’t necessarily take all.

Claire Seymour

Agrippina - Joyce DiDonato, Nerone - Franco Fagioli, Poppea - Lucy Crowe, Ottone - Iestyn Davies, Claudio - Gianluca Buratto, Pallante - Andrea Mastroni, Narciso - Eric Jurenas, Lesbo - José Coca Loza; Director - Barrie Kosky, Conductor - Maxim Emelyanychev, Set designer - Rebecca Ringst, Costume designer - Klaus Bruns, Lighting designer - Joachim Klein, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 23rd September 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Agrippina%20title%20ROH.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Agrippina: Royal Opera House product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Agrippina (ensemble)Photo credit: Bill Cooper

September 23, 2019

Billy Budd in San Francisco

Dutch conductor Lawrence Renes’ seascapes were deeply and powerfully drawn, his battle was monumental, his moral confusion was terrifying, his defeat was shattering. His orchestra was an aggressive, present player in the telling of Melville’s parable. Britten’s score in this conductor’s hands proves that Billy Budd’s story is not at all as simple as it seems and that its lesson is so bleak and huge that it demands the protection of high art to be borne.

The War Memorial Opera House was built before architectural acoustics was a science. Its acoustic can be mushy and quirky. But for this Billy Budd the San Francisco Opera Orchestra somehow clearly projected the beauty of Britten’s moral ideal of handsomeness in a stunning display of colors and volumes and textures. The diction of the opera’s protagonists was crystal clear, every word was fully understandable in the hyper British-like sounds of careful musical diction. It was a remarkable feat.

This was the 2010 production from Glyndebourne by British theater director Michael Grandage and his designer Christopher Oram, seen at the Brooklyn Academy in 2014 to great acclaim. The set is the exaggerated super structure of a British man-of-war called the Indomitable. It is the world of 40 male San Francisco Opera choristers impressed into service as its crew, along with 15 or so more sailers who have names, plus the ship’s captain and his officers and a number of Ship’s Boys.

These 80 inhabitants of the Indomitable populate its globe-shaped world from which no one will escape, not even Billy Budd who, in death, remains alive as the embodiment of a critical enigma of our existence — can good and beauty actually exist in this world? The Grandage production implies that no, it cannot. At the end of the opera the Indomitable’s captain, the now old Starry Vere, the Indomitable’s moral conscience, stands alone on the stage. He continues pondering the enigma as he has since the moment Billy Budd was hung. He looks us straight in the face to tell us that he could have saved Billy Budd but did not. Black out.

Like Peter Grimes and Aschenbach (Death in Venice) the Indomitable’s Captain Vere is a tenor. But here tenor William Burden’s voice is neither heroic nor is it cerebral. Mr. Burden is a fine singer and actor who does not project force of personality. This allows us to perceive Captain Vere as an abstract player in a moral drama, not as an individual man in the throes of crisis. His most telling moment was when he prepared himself to tell Billy that he will be hung. He stood alone in white light, lost within his dilemma, his voice taking on unexpected new beauty, determining the tragic irony that Billy’s goodness must be destroyed.

John Claggart, the Indomitable’s master-at-arms (policeman) was sung by bass Christian Van Horn. Mr. Van Horn is of towering height and is a fine actor of beautiful voice. This Claggart was not a tormented, sexually disturbed character (though his response to Billy is sexually charged) but a towering force of order who must bow to all authority while defeating any threat of enlightenment that might challenge that authority. The handsome beauty, the spiritual freedom of Billy Budd had to be destroyed by any means possible as it awakened enlightenment — perhaps in the master-at-arms himself, and certainly in the seamen.

Billy Budd was sung by baritone John Chest. Mr. Chest possesses a focused dark and beautiful voice. He is of small stature and wily. Of the three principals (Vere, Claggart and Budd) he is the one who becomes the real, suffering human being. He finds a surpassing human sympathy for his fellow men in his very moving death vigil, though he fails to accept that he cannot be handsome and good. Britten’s opera teaches us that we cannot allow beauty to exist as it may challenge order. We must therefore search for its flaw and seize upon this flaw to destroy it. Billy stuttered.

Once Billy is condemned he is led off the stage. We do not see him ascend to the yardarm. He will not be seen as a Christ figure offering salvation. His brute disappearance leaves the world without beauty. Just like Moby Dick who challenges and threatens man, Billy Budd too challenges and threatens men. Both Moby Dick and Billy Budd must be destroyed by the men who cannot control them.

The world of the Indomitable is filled with sailors of lively personalities who serve the purposes of the opera’s protagonists. The San Francisco Opera assembled an excellent, appropriate cast of high level character singers who made the world of the Indomitable an artistically valid setting for this Britten masterpiece.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Captain Vere: William Burden; Billy Budd: John Chest; John Claggart: Christian Van Horn; Mr. Redburn: Philip Horst; Mr. Flint: Wayne Tigges; Mr. Ratcliffe: Christian Pursell; Red Whiskers: Robert Brubaker; Novice: Brenton Ryan; Maintop; Christopher Colmenero; Squeak: Matthew O'Neill; Donald: John Brancy; Bosun: Edward Nelson; First Mate: Sidney Outlaw; Second Mate: Kenneth Overton; Novice's Friend: Eugene Villanueva; Dansker: Philip Skinner; Midshipman: Talinn Hatt; Midshipman: Marvin B. Valdez; Midshipman: Curtis Resnick; Midshipman: Lucas Willcuts; Cabin Boy: Benjamin Drever; Arthur Jones: Hadleigh Adams. The San Franciscco Opera Orchestra and Male Chorus, members of the Ragazzi Boys Chorus. Conductor: Lawrence Renes; Production: Michael Grandage; Revival Stage Director: Ian Rutherford; Production Designer: Christopher Oram; Original Lighting Designer: Paule Constable; Revival Lighting Designer: David Manion. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, September 20, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/BillyBudd_SF1.jpg

image_description=Photo copyright Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

product=yes

product_title=Billy Budd at San Francisco Opera

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Christian Van Horn as John Claggart, William Burden as Captain Vere

All photos copyright Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

Vaughan Williams: The Song of Love

This release includes the famous The House of Life, with Kitty Whately, a mezzo-soprano, and songs in German and French, with Roderick Williams, probably the pre-eminent interpreter of English song.

Though the full cycle of The House of Life is now nearly always heard with male voice, even with bass-baritones, the premiere was given at the Wigmore Hall on 2nd December 1904, in the presence of Vaughan Williams himself, with Edith Clegg, a contralto, accompanied by Hamilton Harty. Some of the songs, to sonnets by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, have texts that suggest a man addressing a woman, such as Love’s Minstrels and Heart’s Haven, but the others four are gender neutral. Indeed, Silent Noon, one of the best loved of all Vaughan Williams’ songs, lends itself particularly well to the female voice. The warmth in Whately’s timbre enhances the image of high summer langour, where “hands lie open in the long fresh grass”, the piano gently palpitating. Whately breathes tenderness into the phrase “All round our nest, far as the eye can pass, are golden kingcups fields with silver edge” One can almost feel the vista, and endless horizons. But the “visible silence, still as the hourglass” cannot last. “Deep in the sun-searched growths the dragonfly hangs…” Dragonflies die, their splendour brief and doomed. Whately’s voice seems to hover, making the passionate final declaration ever more poignant. “O! clasp we to our hearts, for deathless dower”. The final phrase “the song of love” (hence the album title) can be a little too high for some male voices but poses no problems for a mezzo-soprano. Though the cycle is The House of Life, the texts deal with Death, often as a strange visitor, as in Death-in-Life, but the overall impact, given the understatement of Vaughan Williams’ settings, suggests that happiness, and life, must be cherished while it lasts.

In the Three Old German Songs (1902) Vaughan Williams explored medieval German song, capturing an archaic nature rather different from folk song, German or English. The setting of To Daffodils on this set comes from a manuscript found at Gunby Hall, which the composer visited regularly. This differs from the 1895 setting of Robert Herrick’s poem in that the short lines ebb and flow from quietness to climax, much like Vaughan Williams’ Orpheus and His Lute (1903). In the Four French Songs, from 1903-4, Vaughan Williams sets medieval French song, Quant li Louseignolz, for example rather than “Quand le Rossignol”, a song with connections to knights who took part in the Crusades. Thus, the studied “medieval” formality. Roderick Williams has no peer in English song, though his French is less idiomatic, but he’s a natural communicator. Here, his delivery brings out the special qualities in these songs, with their stylized formality, very different from folk song and indeed from later French song. There may well be a connection between these songs and Love’s Minstrels in The House of Life, with its “modern” take on medievalism.

With Buonaparty (1908) Roderick Willliams is back on home ground, his delivery animated, crackling with character. This is one of Vaughan Williams’ only two settings of Thomas Hardy’s poems though, as we know from his Symphony no 9, he knew Hardy’s Tess of the d’Ubervilles and the evocations of Wiltshire and Wessex. Perhaps the composer didn’t warm to Hardy’s other values. Gerald Finzi, who did understand Hardy’s irony and lack of deference, set more Hardy than anyone else. Finzi’s setting of Hardy’s Rollicum-Rorum quite explicitly satirizes populist war mongering. Roderick Williams’ Finzi settings of Hardy are essential listening, not only for the dynamism of his performances, but for what he reveals of Finzi’s feel for Hardy as iconoclast. RVW’s Buonaparty was intended though not used for Hugh the Drover. It’s robust, with a jolly refrain, but not especially perceptive.

With The Willow Song (1897), followed by Three Songs from Shakespeare (1925), Kitty Whately sings some of Vaughan Williams’ settings of Shakespeare. This version of Orpheus and His Lute is almost neo-classical, its refinement more subtle than the better-known earlier version. With The Spanish Ladies (1912) and The Turtle Dove (1919-1934), Roderick Williams returns to classic Vaughan Williams, the first based on a sea shanty, the second on an old ballad collected by the composer from a traditional singer’s performance at the Plough Inn, in Sussex in 1904 . These set the context for Two Poems by Seumas O’Sullivan,The Twilight People (1905) and A Piper (1908) published in 1925, when the composer was working on Riders to the Sea. O’Sullivan was the pen name of James Sullivan Starkey, a Dublin journalist. The plaintive lines may reflect Vaughan Williams’ knowledge of Ireland, through the prism of W B Yeats and J M Synge. Whately and Williams conclude with two duets based on German folk songs, in English translation, Think of me and Adieu. Though Albion recordings cater to a very specialized market, this set is very well planned and performed: a good introduction for those wanting to delve deeper into Ralph Vaughan Williams and the sources of his inspiration.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Song-of-Love-Cover.png image_description=Albion Records ALBCD037 [CD] product=yes product_title=Vaughan Williams: The Song of Love product_by=Kitty Whateley (mezzo soprano); Roderick Williams OBE (baritone); William Vann (piano) product_id=Albion Records ALBCD037 [CD] price=$18.99 product_url=https://amzn.to/2kzCSNfDear Marie Stopes: a thought-provoking chamber opera

Such was the ‘best New Year resolution’ that birth control advocate and sex-advice writer Dr Marie Carmichael Stopes (1880-1958) ever made, according to archival material from the Wellcome Collection. Stopes’ words form the closing lines of Alex Mills’ chamber opera, Dear Marie Stopes, which was presented at Kings Place this weekend, following the premiere in August 2018 in the Reading Library of the Wellcome Collection, as part of that year’s Tête à Tête festival.

In December 1929, advertisements appeared in several British journals announcing the publication of Mother England: A Contemporary History Self-Written by Those Who Have No Historians . This collection comprised almost 200 letters from working-class mothers, each one beginning, “Dear Dr Stopes”. In highlighting the desperation of the poor for “some advice how to prevent any more little ones coming”, Stopes inextricably linked the alleviation of poverty with the need for birth control, presenting her book as ‘a true history of the common people [that] has never yet been written’. [1]

H.G. Wells called it ‘a most striking and useful book’, while Arnold Bennett found it ‘rather awful - in the right sense’. Not everyone was positive: the Secretary for the Society of Authors, St John Ervine, complained: ‘Marie Stopes is a bloody nuisance. She worries the life and soul out of me about Birth Control … and seems to have nothing to do but bounce about the earth, shoving her nose into what doesn’t concern her. Too much energy and not enough sense.’ Indeed, Stopes herself said that Married Love: A New Contribution to the Solution of Sex Difficulties , the guide to sex and marriage that she had published in March 1918, had ‘crashed into English society like a bomb shell’.

The Wellcome Collection archives house thousands of the private letters that members of the public, male and female, wrote to Stopes following the publication of that landmark book, which not only sought to educate about sexual desire, health and contraception, but also espoused gender equality. Mills’ librettist, Jennifer Thorp, has selected extracts from these moving personal accounts, and from Stopes’ replies, and woven them into a sequence of vignettes which reveals the range of contrasting emotional, ethical and ideological opinions prevalent during the 1920s.

Alexa Mason (soprano). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Alexa Mason (soprano). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Reading and hearing these very private testimonies in the small Hall Two at Kings Place was a poignant, at times heartrending, experience, though I did wonder whether sung dramatization of these painful accounts is the most appropriate form of presentation. The words on the page speak for themselves, the simple questions and pleas imbued with an essential eloquence and truth. Mills’ musical setting is certainly sensitive to the text. At times the correspondents’ words are spoken rather than sung, and some recorded voices are interpolated (and projected), enhancing both the sense of historical authenticity and our appreciation of the impact and reach of Stopes’ work. Occasionally, the singers employ a quasi-monotonal declamation while the recitative-arioso style of the vocal melodies respects the natural syntax, with some Britten-esque gestures. The accompaniment - for cello (Clare O’Connell), viola da gamba (Liam Byrne) and percussion (Calum Huggan), with occasional electronic additions - is atmospheric but discreet, the two stringed instruments creating interesting textures, both gentle and tense, the percussion enhancing the moments of emotional intensity. The resulting score is quite cinematic in effect, showing the influence, I thought, of John Tavener.

Alexa Mason (soprano), Jess Dandy (contralto) and Feargal Mostyn-Williams (countertenor) reprised their 2018 performances with considerable skill and dedication. The diction was unanimously excellent, the voices clean and clear. Mills blends the three high-register timbres effectively, as the singers assume a variety of character-roles, echoing each other’s words in a manner which builds dramatic intensity; and Dandy’s rich, earthy lower register provides satisfying contrast, creating a broader expressive palette.

The personal confessions and appeals were deeply affecting, sometimes disturbing. There is the woman who has had 14 children, 9 of whom survive, and who is desperate to avoid the further pregnancy which her doctor has told her will probably kill her. And, the man who fears his sexual dysfunction will forever prevent him showing his “girl” the depth of his love. And, the young girl who despairs that the sexual disease she has contracted will deny her the opportunity to become a mother.

Jess Dandy (contralto). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Jess Dandy (contralto). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

For all the merits of the music and the cast, though, there were moments where I found the emotional ‘temperature’ a little uncomfortable - that the individual private experiences were not best served by musical setting and dramatic presentation. It is hard, for example, to find an appropriate way to set lines such as those uttered by a young woman who, when helping her injured fiancé to remove his clothes “couldn’t help but see … His sex organs were very large”. There were discernible chuckles in Hall Two … and when such an exclamation develops into a duet for soprano and contralto in which the traumatised cries, “Oh God”, climb higher and higher, ever more hysterically ecstatic, there’s a danger of ‘that scene’ from When Harry Met Sally coming to mind.

More seriously, the libretto presents the counterviews of those who see Stopes’ work as “not only unwholesome but harmful” and who declare that “No-one will be the better for reading it”, but such opinions, rather than simply being representative of the broader social context, often come across as morally self-righteous and censoriously bigoted. The cast were wearing Thirties’ period costume, but at times such genuine outbursts seemed less historically informative and rather reminiscent of Britten’s Lady Billows with her sanctimonious advocacy of celibacy and celebration of ‘innocence’.

Feargal Mostyn-Williams (countertenor). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Feargal Mostyn-Williams (countertenor). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Also, I wasn’t sure about the judiciousness of assigning a countertenor to sing Stopes’ own words. Certainly, the decision lends a ‘neutrality’ that might be welcome but, while Mostyn-Williams has a rounded and focused voice, when he was asked to expound Stopes’ philosophical and political ethics - “Women’s political freedom is well worth the struggle … Without control over her own motherhood, no married woman can have bodily freedom” - the high-pitched, forte, unvarying vocal line inevitably sounded a little hooty at times.

The constituent parts have obvious and considerable potential, but it was Nina Brazier’s clear-sighted direction which brought them together into a coherent and convincing whole. The musicians were seated on the intimate Hall Two stage, from which a short walkway extended into the audience, bringing the latter close to the singers who at times circled the Hall. Assorted box files were piled on the stage and on a single desk at the end of the causeway. Three present-day archivists tentatively donned protective gloves and began to leaf through the historical documents, so troubled and affected by what they discovered that the fragile papers, with their hand-written appeals in fading ink, fell like feathers to the floor. Absorbed and overcome by the letters’ content, the archivists gave voice to the past, bringing the correspondents to life and transporting us back in time, making tangible the real and often raw human experiences. The sequence of vignettes unfolded naturally over 45 mins, as the characters’ stories interweaved with Stopes’ replies, and with aspects of her own life.

In fact, in seeking to do justice to the broader picture, Thorp’s libretto packs in rather more than it has time to explore in satisfactory depth. We learn, in one of the most affecting episodes, of Stopes’ own miscarriage. Similarly, her interest in eugenics is touched upon. Such brief glimpses of the wider context are very interesting, but only raise further questions. Stopes’ passionate promotion of birth control grew in part out of her concern with eugenics and had a specific ideological purpose. For example, in her 1923 book Contraception, she wrote that it was only when contraception was widely used by “diseased persons” could birth control become “the great preventive measure to arrest the spread of disease and degeneracy throughout the nation”; moreover, Stopes tried to translate her ideology into practical outcomes, founding in 1921 her first birth control centre, the ‘Mothers’ Clinic’ in Holloway, with the aim of protecting the health of women and controlling ‘racial purity’.

Dear Marie Stopes cannot, of course, explore all of the arguments and counter-arguments exhaustively. But, Mills’ chamber opera does reveal the complexity of human experience and relationships which, in this performance at Kings Place, Brazier’s sensitive handling of the material communicated directly.

Claire Seymour

Dear Marie Stopes : Alex Mills (composer), Jennifer Thorp (librettist)

Alexa Mason (soprano), Jess Dandy (contralto), Feargal Mostyn-Williams (countertenor), Liam Byrne (viola da gamba), Clare O’Connell (cello), Calum Huggan (percussion); Nina Brazier (director), Gareth Mattey (assistant director), Lucia Sánchez Roldán (video and lighting design), Tyler Forward (video programmer), Alexa Moore (costumes), Kate Romano (producer), Dr Lesley Hall (archivist)

Hall Two, Kings Place, London; Saturday 21st September 2019.

[1] For a detailed account, see A.C. Geppert (1998), ‘Divine sex, happy marriage, regenerated nation: Marie Stopes's marital manualMarried Love and the making of a best-seller, 1918-1955’, Journal of the history of sexuality, 8(3): 389-433.

Photo credit: Robert Workman

September 22, 2019

A revelatory Die schöne Müllerin from Mark Padmore and Kristian Bezuidenhout

Michael Steinberg’s prognosis, expressed in The Boston Globe in July 1976, is taking rather longer to be fulfilled than the eminent classical music critic, writer and lecturer imagined. But, this performance of Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin by Mark Padmore and Kristian Bezuidenhout at Wigmore Hall will surely have done much to win converts to the cause which Steinberg described over 40 years ago as a ‘Fortepiano Revolution’.

Standing at the centre of the Wigmore Hall platform, the grand fortepiano from the workshop of Christoph Kern (located in Freiburg im Breisgau in the Upper Rhine plain) was a beautiful sight to behold, its glossy chestnut-cherry colour wood gleaming with an elegant grain, its graceful curves evincing a quiet stylishness and assurance.

As Wilhelm Müller’s tale of the young miller’s journey - from awakening and hope through delusion to rejection, despair and death unfolded - Bezuidenhout revealed the expressive responsibility with which Schubert endows the fortepiano part in ways that, for this listener at least, were quite revelatory. The lightness of the sound was coloured by a judiciously applied sharpness of attack, the clarity animated by such alertness, the bass line robust but lithe. This was evident from the opening bars of ‘Das Wandern’, where the low bouncing bass line and the rhythmic articulation of the rollicking right-hand figuration possessed an unusual airiness, perfectly capturing the buoyant optimism of the miller as he sets out, untroubled by desire and delighting in the rushing brook that the piano ceaseless motion embodies. Similarly, in ‘Wohin?’ Bezuidenhout was able to achieve a truly hushed pianissimo, the fluttering right-hand transparent and elegant, the syncopated bass eloquently swaying. The rapid flickers in ‘Halt!’, as the miller espies the mill among the alder trees, were gleamingly defined.

If dynamic range is not one of the fortepiano’s strengths, then Bezuidenhout showed us that the instrument does offer variety, of timbre, texture and colour. The softest passages were beautifully executed, with stylish discernment and detail. Moreover, the more rapid decay of the fortepiano’s tone seemed to become an integral expressive element. For example, the quaver-chords in the central section of ‘Am Feierabend’ were not only crystal-clear and light, but were followed by a distinct silence, the short rest evoking the slowing of the mill-wheel and the young man’s growing weariness, but also his unsettling self-doubts as he wonders if he can inspire love in the girl who has bewitched him. Similarly, at the close of ‘Danksagung an den Bach’, the gentle diminution of the postlude, with its delicate ornamentation, acquired an intimate, almost confessional, quality.

Kristian Bezuidenhout (fortepiano). Photo credit: Marco Borggreve.

Kristian Bezuidenhout (fortepiano). Photo credit: Marco Borggreve.

And, it was a quality that Mark Padmore’s communication of the cycle’s musical narrative wonderfully sculpted and enhanced. Initially, this miller was perhaps not quite the carefree adventurer of Müller’s opening poems. Rather, his purposefulness already seemed tempered by a proclivity for dreamy detachment, but Padmore’s relaxed, beautifully enunciated presentation of the text had the effect of entrancingly drawing the listener into the miller’s psyche. In ‘Danksagung an den Buch’ the tenor seemed to distinguish the words spoken aloud, to us, and those that are heard only within his own mind, and the major/minor alternation was movingly expressive. The floating tenderness of the girl’s sweet ‘good night’, which the miller dreams into being at the close of ‘Am Feierabend’, effected a shift in the expressive temperature in the following ‘Der Neugierige’, the vocal fluency and prevailing ‘simplicity’ suggesting a growing self-delusion which blossomed in the following ‘Ungeduld’ in intense assertions of devotion: “Dein is mein Herz, und soll es ewig bleiben.” (My heart is yours, and shall be forever!)

The uneasy balance of confidence and anxiety dissolved, however, towards the close of ‘Des Müllers Blumen’ where the spaciousness of the fortepiano’s compound rhythms and the delicacy of Padmore’s pianissimo intimated the ‘rain of tears’ to come, in ‘Tränenregen’. Here, again, the move to the minor key in the closing verse, allied with a carefully crafted dynamic rise and retreat, powerfully communicated the miller’s piercing yearning. Such longing was transformed into the ebullient confidence of ‘Mein!’, and the tender ecstasy of ‘Pause’ in which Padmore’s sweet head-voice seemed to embody the transfiguring beauty of the miller’s lute itself, as the breeze brushes gently across its strings, and also the fragility of the miller’s illusions.

The latter were shattered with the arrival of the hunter. The miller was by turns defiant and despairing, his defeat by his romantic rival confirmed by the quasi-reluctance of the fortepiano’s staccato progressions in ‘Die leibe Farbe’ and Padmore’s ghostly, dissolving lament: “Die Heide, die heiss ich die Liebesnot,/ Mein Schatz hat’s Jagen so gern.” (I call the heath Love’s Anguish, my love’s so fond of hunting.) The ‘world beyond’ took an ever more inescapable hold. The dynamic alternations and Padmore’s subtle verbal nuances in ‘Die böse Farbe’ revealed the miller’s fragile grip on the real, while the fortepiano’s delicate pianissimo quavers at the start of ‘Trockne Blumen’ seemed to come from ‘elsewhere’. The exquisite gentleness of the vocal line in the latter made the sudden forcefulness of the close - again, a telling shift from minor to major key in the penultimate verse - all the more troubling.

One remembers that it was in 1823 that Schubert contracted syphilis, and that it was during his hospital stay that year that he composed parts of Die schöne Müllerin. The despair that he expressed in a letter to a friend, Leopold Kupelwieser, in March 1824 was poignantly evident in Padmore’s performance: ‘I feel myself to be the most unhappy and wretched creature in the world. Imagine a man whose health will never be right again, and who in sheer despair over this ever makes things worse and worse, instead of better; imagine a man, I say, whose most brilliant hopes have perished, to whom the happiness of love and friendship have nothing to offer but pain […] “My peace is gone, my heart is sore, I shall find it never and nevermore” I may well sing now, for each night, on retiring to bed, I hope I may not wake again …’

But, Padmore’s lament for what is lost was lifted by the miller’s acceptance of his mortality and by the brook’s promise of renewal and eternity: “Rest well, rest well! Close your eyes! Weary wanderer, you are home.” Despite the melody’s twists of pain, the conversation between the miller and the brook had a compelling fluency that spoke of the miller’s undeniable fate. For the final song, ‘Des Baches Wiegenlied’, Padmore moved to the side of the stage, the emptiness at the centre confirming the miller’s death, the brook’s lullaby ethereal, beatific, calling from beyond, ever more distant until a slight warming - “Schlaf’ aus deine Freude, schlaf’ aus dein Leid!” (Rest from your joy, rest from your sorrow!”) - confirmed the miller’s peaceful union with nature.

Steinberg’s 1976 article with which this review began was a profile of the American fortepianist and scholar Malcolm Bilson, who has been one of the principal evangelists for the renaissance of the instrument. Bilson has remarked, ‘Perhaps it is wrong to put the instrument before the artist, but I have begun to feel that it must be done’. Well, perhaps. But this recital at Wigmore Hall was the occasion of a remarkable unity between the musicians and their respective instruments, an integration of sound and sense which I feel privileged to have experienced.

Claire Seymour

Mark Padmore (tenor), Kristian Bezuidenhout (fortepiano)

Wigmore Hall, London; Friday 20th September 2019.

Photo credit: Marco Borggreve

September 21, 2019

O19: Fiery, Full-Throated Semele

This was a stunning performance of true festival quality, with a cast and creative team operating at the top of their game. Moreover, the intimate Perelman Theatre in the Kimmel Center is a perfect venue for Baroque opera. Every nuance lands, every arched eyebrow communicates, every whispered phrase shudders throughout the house.

Leading the cast, Amanda Forsythe proved a flawless Semele, her freely produced, floating soprano tinged with silver and at first weighted with an immensely appealing melancholy. As she becomes involved with Jupiter, her lyric delivery becomes imbued with more libidinous warmth and by the time she reaches the treacherous demands of Myself I Shall Adore, Ms. Forsythe is fearlessly, effortlessly hurling out roulades, acuti, and ornamentation at such a dizzying clip, your heart starts racing just to keep up. Hers is a towering achievement.

Athamus (countertenor Tim Mead),

Semele (soprano Amanda Forsythe),

and Cadmus (bass baritone Alex

Rosen).

Athamus (countertenor Tim Mead),

Semele (soprano Amanda Forsythe),

and Cadmus (bass baritone Alex

Rosen).

Matching her note for note in intensity and artistry is the sublime mezzo Daniela Mack, who has never been heard to better advantage as she doubled the disparate roles of Ino and Juno. As the former, she imbues her rich tone with a plangent world weariness that is melting, and heartrending in its ravishing effect. As the imperious Juno, Ms. Mack crackles with self-satisfied pomposity, her evenly produced vocalizing zinging out and dominating all within earshot. Her commanding, take-no-prisoners rendition of Iris, Hence Away was one of the evening’s several showstoppers, justifiably greeted with sustained roars of approval.

Erik Shrader’s substantial vocal gifts were also well displayed with his triumphant, strapping traversal of Jupiter. Having had ample chance to ravish us with some impossibly accurate and delightful rapid-fire melismas at full throttle, he plied his honeyed tenor and scaled it to nearly a filigree as he voiced a divinely sweet Where E’er You Walk. We scarced breathe, lest we break the sublime perfection of his music making.

Sarah Shafer was a sure-voiced Iris, displaying a wicked, uninhibited sense of comedy, all the while singing with secure freedom. Ms. Shafer’s creamy, gleaming soprano is a model of polished, poised perfection. She made a true star turn out of her rather licentious physicalization of the aria when she describes the pleasure palace that Jupiter has created for Semele.

Alex Rosen as Somnus and Daniela

Mack as Juno

Alex Rosen as Somnus and Daniela

Mack as Juno

Alex Rosen does admirable double duty as Cadmus and Somnus. Mr. Rosen’s barrel-toned, massive bass made for a weighty, troubled Cadmus, and he spun out his arching phrases with luminous tone and impressive legato. As Somnus, this gifted singer imbues his assignment with a woozy sexiness, manly torso bared, lulled from sleep but now clearly ready to be on the prowl. This is a major vocal instrument and potent talent that is already impressive and promises much to come.

Tim Mead sported a secure, crystal clear countertenor in the small role of Athamas. His highly musical, incisive portrayal made us wish that Handel had given him more to sing, but even among this starry cast that had many meatier moments, Mr. Mead was memorably committed. This production includes an unscripted Principal Dancer, Lindsey Matheis, that is a shadow double of the hapless Ino.

Ms. Matheis was a key component of the concept’s success, as she hurled herself into anguished twisting and turns with total disregard for gravity. She was not alone in embodying churning emotions in movement, joined as she was by dance corps Justin Campbell, Sydney Donovan, Jesse Jones, and Daniel Mayo, who meticulously, tirelessly executed the inspired choreography by Gustavo Ramirez Sansano. While his devised movement recollected the work of Pina Bausch, Twyla Tharp, William Forsythe and others, Mr. Sansano provided his own vision, as the group ceaselessly writhed, rolled, tumbled, toted, and gesticulated to profound effect.

Semele (soprano Amanda Forsythe)

confronts Jupiter (tenor Alek Shrader) to

demand he appear to her in his immortal

form of thunder and lightning.

Semele (soprano Amanda Forsythe)

confronts Jupiter (tenor Alek Shrader) to

demand he appear to her in his immortal

form of thunder and lightning.

In the program notes, director James Darrah discussed the evolvement of movement in his interpretation of the piece. Indeed, the entire evening was not so much enacted as danced, with Elizabeth Braden’s excellent chorus joining in with awesome singing and uninhibited physicality. The precision of their execution was in fact one of the production’s true glories.