October 31, 2019

The Dallas Opera Cockerel: It’s All Golden

Since that outdoor New Mexico venue is celebrated for its open upstage wall that affords sunset views of the Sangre de Cristo mountains, I wondered how the scenic “environment” might adapt to an indoor proscenium house. The answer is, quite wonderfully well.

If anything, I found Gary McCann’s industrial grid work scenic elements even more effective. Although appearing more compact on the Winspear Opera House stage, the whole artful edifice seemed better placed, especially the sweeping skateboard-like ramp/wall stage right that also served as a projection screen.

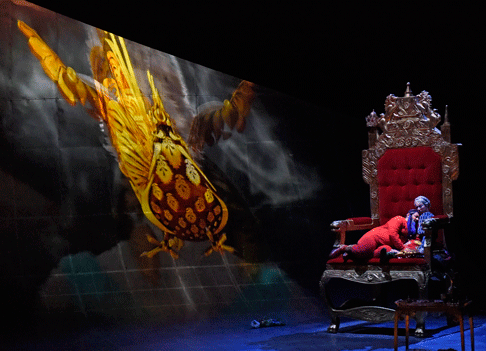

For Act II’s “mountain pass,” a series of broken rings and girders was added upstage, a stacking of half-finished roller coaster loops perhaps subtly suggesting a rooster’s tail. The raked stage floor included an effectively used trap door, that allowed for the loopy entrance of King Dodon, seated with legs splayed on a greatly over-sized gilded throne, recalling (intentionally?) Lily Tomlin’s Laugh-In persona, Edith Ann, who was dwarfed by the huge chair she occupied.

Driscoll Otto’s inventive projection design remains one of the production’s glories, especially when he utilizes the upstage back wall in Acts Two and Three, after intermission. Curiously, that upstage screen was not utilized in Act One and the playing space lacked the maximal visual depth it might have had. Of course, in Santa Fe that upstage space was open to nature and was not a projectable surface, but were this production package to have further life, I would urge adding upstage projections in Act I. The animated cockerel proved an especially effective decision.

Mr. Otto’s inspired creations sometime even spilled dizzyingly onto the proscenium, and his work was beautifully complement by Paul Hackenmueller’s amazing lighting design, which was a malleable marvel of vibrant color washes, selectively deployed follow spots, dramatic side-lighting, austere down-lighting, and all manner of moody illumination that perfectly suggested just the correct atmosphere, ranging from brutally tragic to playfully comic.

Mr. McMann also provided a colorful and varied costume design, a veritable explosion of folk wear that riffs on peasant Matroyushka dolls, Orthodox religious icons and pompous royalty with equal aplomb. The King/Tsar was presented as the emperor that has no clothes on, caped but with a distended beer-belly in his red BVD’s, an inspired touch. And a final costume reveal near the end suddenly alters the tone and period, and injects contemporary resonance into the political satire, should any still be needed.

With an almost entirely new cast, director Paul Curran has recreated and further enhanced an excellent arsenal of stage business and blocking. The use of the huge throne was notably daffy, with the King, his dimwitted progeny, General Polkan, and even housekeeper Amelfa clambering on, over, and off this huge piece, ducking under armrests, standing on the seat and arms, leaping to the floor, and clambering back up on the rungs of the braces over and over again. That they did this entertaining workout routine seemingly tirelessly is a testament to their stamina, fitness, and dedication.

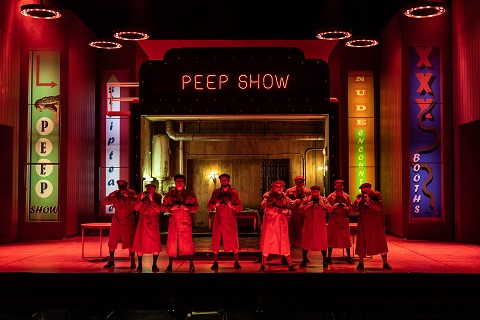

I still loved that the Queen of Shemakha was announced and accompanied by a bevy of white clad showgirls brandishing white ostrich plume fans, like an upscale supper club floor act. Later, these chorines and their feathers conspired with King Dodon in a Ziegfeld-Follies-routine-gone-wrong, which found the dippy monarch hilariously bumping, grinding, and popping a few outrageous hip moves that had the audience giddy with amusement.

Mr. Curran not only used the chorus ingeniously and meaningfully during longer orchestral passages to visualize the action, but also devised well-choreographed interplay between the principals that began as lighthearted political commentary and then morphed into sobering tragedy as the stakes were inexorably raised.

Conductor Emmanuel Villaume had led a most persuasive reading in Santa Fe and he has only honed his interpretation to an even more telling rendition. Nothing about this challenging score eludes him or his finely tuned group of Dallas instrumentalists. The composer remains an acclaimed orchestrator to this day, and Maestro Villaume elicited every drop of color and variety of effect from this wide-ranging score. The exquisite woodwind soloists are arguably first among equals for their spirited contributions, many of which conveyed an effortless exoticism and piquant commentary.

The brass fanfares and motifs were commandingly rendered, and the percussive effects were tastefully stirring. The strings could effortlessly segue from regaling us with banks of lush and ravishing ensemble work, to providing sardonic, characterful commentary. This was an exceptional reading of a knotty, difficult piece, and Villaume proved to be completely in command of his large forces, to include Alexander Rom’s exquisitely prepared chorus. The soloists, too, were uniformly excellent.

Two holdovers from their Santa Fe triumph were Barry Banks and Kevin Burdette. Of the former I had written: “Barry Banks was born to play the Astrologer.” I remain convinced of that fact, and if anything, Mr. Banks’ utterly secure, freely produced tenor rang out even more thrillingly on this occasion as he made child’s play of the role’s forays into the stratosphere, without ever sacrificing beauty of tone. And Mr. Burdette seems to be having even more fun than before as General Polkan, characterized by his rock-solid bass singing, coupled with securely delivered Cassandra-like prophecies, loose-limbed physicality, and a most winning, mustache twitching comic impersonation.

Nikoloy Didenko’s bass-baritone anchored the show as the clueless, pliable King Dodon. At first, his delivery seemed just a bit muted, the rich tones of his lower and middle register thinning out a bit at the very top. At the matinee I attended, Mr. Didenko warmed substantially to his task as the show progressed, and he was soon firing on all cylinders, the top turning over with sheen and power. Although his voice has good thrust and has a nice hint of metal, this is a somewhat lighter instrument than I have experienced in the part, although no less effective, since it was performed with unerring musicality. Best of all, Nikoloy was a committed, no holds barred comedian, able to throw himself into the wide-ranging serio-comedic demands of this lengthy role with commendable abandon.

Viktor Antipenko (Prince Guidon) and Corey Crider (Prince Afron) were true luxury casting as the King’s boneheaded sons. Hmmm, a clueless, uninquisitive, vain head of state with two clueless male offspring…where have we encountered this before? But I digress…Mr. Antipenko deployed a freely ringing Heldentor which imbued the brief part of Guidon with burnished vocal pleasures, while Mr. Crider’s imposing bass-baritone pinged off the back wall with powerful beauty. Between the two of them, they not only delivered some of the show’s best vocalizing, but also wholeheartedly bought into the political mockery and silliness of purpose.

Jeni Houser’s pliant, soaring coloratura soprano was so assured and attractive in her offstage declamations as the titular Cockerel, that I wished she had been given more to sing. Lindsay Ammann’s rolling, robust contralto ably served and informed the character of the servant Amelfa. Ms. Ammann’s rich intonations at the lowest reaches of the part were especially impressive, although her registers are well knit and uniformly, powerfully pleasing. Lindsay’s ‘goof’‘with a “parrot” prop was particularly memorable for its ingenuity.

Rounding out the cast was the Queen of Shemakha as embodied by the delectable coloratura soprano, Olga Pudova. First, she is an attractive, pert, petite young woman with the requisite beguiling physical presence. There are precious few sopranos who could not only sing the role this ravishingly, but could also simultaneously, uninhibitedly, strip from a flowing gown and headdress to a skimpy, two-piece harem showgirl bikini.

Ms. Pudova’s gleaming voice is on the smaller, lyric side, but she has a superior sense of line and focus that easily communicates in the house. Her coloratura is flawlessly rendered and her sly manner with a comic turn of phrase imbues her singing with infectious joy. While she vamped the King without inhibition, she could turn on a dime and become a deadly, manipulative siren when the drama demanded it.

If her finely spun phrases in alt were her crowning achievement, she could not quite summon the requisite ominous weight for the more sobering dramatic (and musical) turn of events. Still, Olga emphatically proved that she was the undisputed Queen of all she surveyed, and the audience responded with enthusiastic acclaim.

What a pleasure to encounter this worthy production again and have the opportunity to appreciate so many artists new to me that made for such a rewarding afternoon in the theatre. The Dallas Opera is to be lauded for bringing to life this operatic rarity, a Cockerel that was golden in every way.

Happy Tenth Anniversary at the Winspear venue. And many more.

James Sohre

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: The Golden Cockerel

Astrologer: Barry Banks; King Dodon: Nikoloy Didenko; Prince Guidon: Viktor Antipenko; General Polkan: Kevin Burdette; Prince Afron: Corey Crider; First Boyer: Jay Gardner; Second Boyer: Christopher Harrison; Golden Cockerel: Jeni Houser; Amelfa: Lindsay Ammann; Queen of Shemakha: Olga Pudova; Conductor: Emmanuel Villaume; Director: Paul Curran; Set and Costume Design: Gary McCann; Lighting Design: Paul Hackenmueller; Projection Design: Driscoll Otto; Chorus Master: Alexander Rom

image=http://www.operatoday.com/GC_First_0289_C.png image_description=Photo credit: Karen Almond, Dallas Opera product=yes product_title=The Dallas Opera Cockerel: It’s All Golden product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id=Photo credit: Karen Almond, Dallas OperaLuisa Miller at Lyric Opera of Chicago

The role of Luisa is sung by Krassimira Stoyanova and that of Rodolfo, known first as Carlo, by Joseph Calleja. Luisa’s father Miller is performed by Quinn Kelsey, and Count Walter, father of Rodolfo, is Christian Van Horn. The Duchess Federica is sung by Alisa Kolosova, while Solomon Howard performs as Wurm, a subordinate of Count Walter. The Lyric Opera Orchestra is conducted by Enrique Mazzola, and the Lyric Opera Chorus is prepared by its Chorus Master Michael Black. The production, owned by the San Francisco Opera, is by Francesca Zambello. Sets, costumes, and lighting are designed by Michael Yeargan, Dunya Ramicova, and Mark McCullough respectively. Mr. Howard makes his debut at Lyric Opera in these performances.

In the first scene of the opening act Luisa stands apart at stage right while the chorus of villagers seems to fill much of the remaining open space. In this production the sets are conceived with an imaginative use of an open space at stage rear. The space is at times covered - in this first scene with a cloth bearing illustrations that denote an Alpine landscape - or it is left open to accommodate entrances or departures altering the focus of performers on stage. The position of society as a witness to individual or familial misfortune in love is a frequent device in the genre of late eighteenth-century “bourgeois tragedy” to which Verdi’s source by Friedrich Schiller belongs. For the lovers themselves the tragedy lies in the unbridgeable distance occasioned by class.

Once the villagers sing their good wishes to Luisa on this her birthday, Miller enters to add his paternal compliments. In this role Mr. Kelsey makes the most of the declamatory phrasing which expresses both joy and apprehension. His flexible baritone assumes an ominous cast when he broaches the topic of an “ignoto” (“unknown”) Carlo with his daughter. In her first aria, as a response to Miller, Ms. Stoyanova sings of her love for this newcomer [“m’amo, l’amai” (“He fell in love with me, and I with him”)] after calming her father’s fears. Rather than singing the individual notes in a skipping progression suggesting the character’s infatuation Stoyanova expresses the line in sustained pitches, so that Luisa effectively sounds more mature.

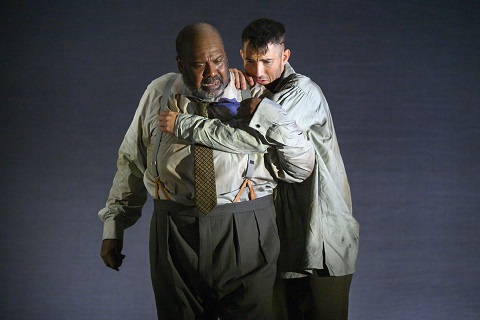

Almost immediately Carlo enters. In this role Calleja displays the focused, urgent commitment so vital to a principal Verdian tenor. The impetuous lover Carlo and Luisa exchange their assurances of continued devotion. The protagonists sing in succession and jointly of language’s inability to express their love, during which Calleja and Stoyanova sing with rounded, full-voiced lyrical ardor. Their momentary disappearance with the crowd into the Alpine church is followed by the appearance of Wurm and his confrontation with Miller.

The role of Count Walter’s deputy Wurn is performed with imposing force by Mr. Howard, yet his voice retains a flexible line with considerable variety in low pitches. His opening words to Miller, “Ferma ed ascolta” (“Stop and listen”) are rife with menace, just as the following address Howard expresses Wurm’s “gelosia” with accelerating pressure while assuring Miller that he will not relinquish his desires for Luisa. In the gloriously lyrical response, “Sacra la scelta” (“Sacred is the choice”) Mr. Kelsey’s Miller resists the threats of authority and elaborates on his duties as father and protector. Kelsey performs this central aria with accomplished legato as well as decorative touches to enhance repeated phrases such as “Non son tiranno, padre son io” (“I am not a tyrant, I am a father.”). Kelsey is especially adept at singing Verdi’s descending lines with emotional force, just as his extended pitches at the close emphasize the significance of this aria.

In general, the low voices in the cast leave an especially strong impression. In a subsequent scene in the noble’s palace Count Walter muses on his position. He has summoned Rodolfo in order to force a meeting between his son and the Duchessa as a prospective bride. Mr. Van Horn’s performance resonates with noble demeanor, his steadfast convictions on family and obligation reflected in his urgent declamation of “Il mio sangue, la vita darei” (“I would give my blood, my life”), followed by forte top notes matching the orchestra and a concluding phrase descending to the depths of the Count’s soul. At the same time when confronted later by Rodolfo’s awareness of his secret Van Horn expresses shades of vulnerability which his character is eager to conceal. Music from afar, growing gradually in volume, announces the Duchess’s arrival. Ms. Kolosova’s imaginative entry on a stylized horse heralds her characters noble lineage while causing awe among those who greet her. In her pivotal scene with Rodolfo Kolosova’s solid vocal range captures the Duchessa’s importunate declarations with chilling emotional fervor. Calleja’s requests to be released from this grip are equally exciting as the scene emerges as one of the most dramatically exciting of the production. The duet also sets into motion the remaining ensembles of the first act culminating in the near arrest of Luisa and her father as well as the rupture between father and son.

The scenes of Act II and III are considerably more intimate than the public gaze and pageantry associated with preceding, longer act. The dramatic structure of Act II allows for the intrigue from the German source (“Kabale”) to be realized. Despite Rodolfo’s threat to his father, Miller has been jailed before the start of the nexr act. Luisa must agree to Wurm’s demands in order to aid her father. At the scene between Wurm and Luisa Stoyanova projects an heroic determination new to her character just as Howard’s selfish insincerity as Wurm seems to grow with each line. By insisting that she sign a letter committing herself to Wurm, this henchman of Count Walter provides testimony for Rodolfo’s eventual mistrust of his beloved. Calleja’s reaction captures the wistful mood of “Quando le sere al placido” (“When at evening in the calm light”) and recalls his bristle of outbursts at the close of the first act. Yet by the start of Act III the protagonist lovers have here reached a series of fatalistic resolutions. Both Stoyanova and Calleja sing poignantly of their renewed devotion but society’s threat now limits their love to the time they have left until the poison takes effect. Once Wurm is killed in a parting blow, Count Walter is left alone with his secret and its torments.

Salvatore Calomino

image=http://www.operatoday.com/luisa_miller_6.png image_description=Joseph Calleja and Krassimira Stoyanova [Photo courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago] product=yes product_title=Luisa Miller at Lyric Opera of Chicago product_by=A review by Salvatore Calomino product_id=Above: Joseph Calleja and Krassimira Stoyanova [Photo courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago]Philip Glass: Music with Changing Parts - European premiere of revised version

Glass’s revision of Music with Changing Parts, which premiered in New York in 2018, doesn’t fundamentally alter the musical patterns, those propulsive rhythms or the sense of predictability in a work which is always unpredictable - what has changed is the lack of astringency, the greater range and just different sounds in a revision which places it between two poles of Glass’s creative output.

If there is one thing which Music with Changing Parts does display it is a discipline to the intricacies of how every bar, every phrase and every line are carefully processed, even if you’re hearing the same ones, multiple times. This is the Boulanger effect on Glass’s early music. But what is equally striking about this particular piece - and this remains true whether you hear it in the original or the revision - is a debt to Stockhausen, if not consciously inspired then certainly as a musical parallel. The Glass of Music with Changing Parts is about the geometry of patterns, the polyvalent, unpredictable randomness which runs through a piece like Klavierstück XI, the clusters of electronic sound which reach a colossal apex and the psychoacoustic effects of voices which recall Stimmung, a work written just a few years before in 1968. What the revision does, and does so well, is turn Music with Changing Parts into an almost full-blown choral piece, and in doing so expand on those overlayered voice frequencies, the kaleidoscopic complexities of long and short vocal sounds into something significantly more minimalist and hypnotic than one usually experiences in Stimmung.

As the title of the work suggests there is nothing fixed about the orchestration of Music with Changing Parts. If I recall, the 2005 performance at Tate Modern used significantly more players than the Philip Glass Ensemble had used on their ground-breaking recording of the work in 1971. Whilst doubling of instruments is an option (as it was for the recording) what the revision does is to simply expand the number of players and instruments (beyond the normal keyboard and woodwind). For this particular performance, that was two horns, two trumpets, a flute, a tenor trombone and a bass trombone. What this does to the tone of the work is to markedly change its musical direction. It can, in one sense, just sound much less radical, much less primitive a score - much of the asceticism has been torn from its pages, its landscape less jagged and now more sensuous, almost opulent. The colours aren’t as shocking or vivid as they once felt; now they seem more tenebrous. In a work which sometimes seemed it was striding multiple musical genres, from minimalist classical to quasi-symphonic clusters of rock (at one time, I rather thought some of this music resembled the cumulative, kinetic power of Santana’s Soul Sacrifice - the 1969, psychedelic Woodstock version, that is), it now sounded comfortably, and eerily, closer to Akhnaten. Not a bad thing - just a different aural experience.

Originally, the use of voices in Music with Changing Parts was strongly tied to the improvisatory geometry of the work - and those voices were in every sense unwritten. The words had no structured meaning, they occurred only at breaks in the playing - and those breaks were themselves determined by the players, not by the score. The notes given out for this performance didn’t make anything clear (in fact, Mr Glass was extremely minimalist in telling us anything about what we were going to hear) so what follows is largely based on how I heard it.

Philip Glass Ensemble. Photo credit: Mark Allan/Barbican.

Philip Glass Ensemble. Photo credit: Mark Allan/Barbican.

If the fundamental randomness of the instrumentation remains largely untouched - that is, patterns of varying lengths, repeated as often as a musician wants - the choral writing is a whole new layer in itself. The momentum is clearly forward-looking, each section sounding different to the previous one. The chorus is divided - and part of the work’s spectral unpredictability is that often only the left or right chorus will sing - though sometimes one experiences the chorus in unison. Quite how far the impact of this is random, of whether the ear will ever be tuning in to one side or the other, to a stereophonic or a more monophonic distribution of sound, is difficult to tell. A choral conductor suggests this is entirely possible. Glass has also opted for a children’s chorus, which if it seems a touch Mahlerian is actually much more inventive. If this is now a work which is about contrast and depth, about the possibility of range and tone, the layers in it have become enmeshed in quite complex textures. The rhythm remains entirely uniform - what feels alien to the original Music with Changing Parts is an exploration of different pitch than we have in the later version.

The performance itself was beyond first rate. If I clearly heard parallels with some of Glass’s later works (especially the operas after Einstein on the Beach) this was an incredibly hypnotic experience. The biggest irony of Minimalism is that its simplicity masks huge complexity. What can seem structurally slight is actually vast in scale. It would be easy to take the virtuosity of the Philip Glass Ensemble for granted, but the concentration, especially from the keyboard players (Lisa Bielawa, Nelson Padgett and Mick Rossi), was of an exceptional quality. This was the kind of performance you were transfixed by - something you watched as well as listened to. This often went beyond music into a kind of visual art.

The London Contemporary Orchestra, who provided the brass players, were entirely immersed in this music. I warmed especially to the dark trombones (Iain Maxwell and Dan West) as well as the piercing and bright trumpet playing (Katie Hodges and Dave Geohagen). The Tiffin Chorus had, I think, something of a challenging evening - but this was a performance which lasted for ninety rather intense minutes. Glass makes few, if any, allowances for the fact that huge amounts of this score is to be sung by children. Much of the rapid repetition of same-note patterns, the varying length and intensity of the notes themselves, the shifts in register or the apparent discretion of the choral conductor were all taxing on them, but they acquitted themselves very well.

At times one sometimes felt that the audio and sound engineering (Ryan Kelly and Dan Bora) felt a touch over reverberant, especially when capturing the voices of the Tiffin Chorus. It was possibly meant to be deliberate. The theory is that Glass came to compose Music with Changing Parts precisely because of the effect of reverberation he heard in a performance of an earlier work. Distraction in this case may well have been purposeful effect. It did little in the end to weaken a performance which had been masterfully conducted from the keyboard by Michael Riesman and the choral conductor, Valérie Saint-Agathe.

The question one might ask after hearing this concert is whether Philip Glass intends this revision of Music with Changing Parts to completely supplant his earlier version. His notes were elusive about this, and I don’t know the answer either. Musically, it was a superlative evening - and I think compositionally it improves on the original. Performances of the latter were a rarity; perhaps this will change that.

Marc Bridle

Philip Glass Ensemble, Michael Riesman (music director), Valérie Sainte-Agathe (conductor), Players from the London Contemporary Orchestra, Tiffin Chorus (James Day - Tiffin Chorus director)

Barbican Centre, London; Wednesday 30th October 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/PGE%20Barbican.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Philip Glass: Music with Changing Parts, European premiere of revised version, Barbican Hall, London product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=Above: Philip Glass EnsemblePhoto credit: Mark Allan/Barbican

October 30, 2019

Time and Space: Songs by Holst and Vaughan Williams

As the label is an offshoot of the Ralph Vaughan Williams Society, its choices are eclectic rather than mainstream, but illuminate aspects of Vaughan Williams’ life and work which might not otherwise be covered in mass market releases. While Albion’s first collection “Heirs and Rebels” presented archive recordings of well known songs by Holst and Vaughan Williams, the choices on this recording places less familiar songs – some unpublished – by each composer beside each other for comparison and also their settings of the same texts.

Holst’s fascination with visionary themes can be glimpsed in “Invocation to Dawn”, from Holst’s Six Songs Op15 H68 (1902-3). This was the first of his settings of his own translation from Sanskrit. It’s contemporary with his The Mystic Trumpeter (1904 rev. 1912), and works like Savitri Op 25 and the Choral Hymns to the Rig Veda Op. 26 (1908-12). While neither Holst nor RVW were conventionally religious, the ardent vocal line and rolling piano part in this song connects to transcendental themes prevalent in that era. Holst includes three settings of Thomas Hardy, “In a Wood”, “Between Us Now”, and “The Sergeant’s Song”, which text Vaughan Williams also used in Buonaparty (1908), which can be heard on the recent “The Song of Love” album, also from Albion. (Please read my review here). Holst’s version is animated, more attuned to the irreverent satire in the poem, with Roderick Williams at his idiomatic best. The suppressed passion in “I will not let thee go”, to a poem by Robert Bridges might remind some of Vaughan Williams’ Silent Noon, from 1904, though Silent Noon is by far the masterpiece.

A E Housman verses inspired Vaughan Williams’ On Wenlock Edge (1909), and also Along the Field (1925-7). These songs, set for high voice and solo violin (Mary Bevan and Jack Liebeck) are exquisite studies in minor key modality, so refined that they seem to hover in mystical trance. In “We’ll to the Woods No More”, the vocal line stretches, with seemingly little dynamic variation, mirrored by the violin. But perhaps that is the point : the mood is so elusive that the song floats away, like a ghost. “Along the Field ”develops the mystery. The plaintive vocal line suggests plainchant, or possibly vespers, for the lovers will soon be parted by death. The leaves of the aspen tree know what lies ahead but cannot speak. “And I spell nothing in their stir” sings Bevan with hushed deliberation. Even the relatively cheerful “In the Morning” is melancholy, and “The Sigh that Heaves the Grasses” drips with portent. The violin part in “Good-Bye” is subtly discordant, picking up on the unspoken emotions of the lad so abruptly dismissed by the object of his affections. The text of “Fancy’s Knell” resembles “Clun” from On Wenlock Edge, though the wordier scansion of this poem doesn’t invite quite such a strong setting. The set ends with “With Rue my Heart is Laden”, also set by George Butterworth, Vaughan Williams’ version even more aphoristic and enigmatic. Although these songs are usually heard with tenor, the silvery timbre of Bevan’s voice, in my opinion, enhances their strange, surreal magic. This performance is so beautiful that it makes this recording an absolute must.

Two settings of A Cradle Song to a text by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, one by Vaughan Williams from 1905, the other By Holst from his Op.16 H6 (1903-5) contrast with Vaughan Williams’ Blake’s Cradle Song (1928) , the composer responding to the greater complexity of Blake’s poem. Holst’s Four Songs Op.14, H14 (1896-98) are fairly early works, setting poems by Charles Kingsley, Henrik Ibsen and Heinrich Heine (both in English translation) and Robert Bridges.

Vaughan Williams’ Bushes and Briars (1908), introduces the group of folk songs in this collection. Bushes and Briars is seminally important, since it was the first song the composer collected in the field, having heard it sung by a labourer in Essex in 1903. It’s been performed hundreds of times in many forms, including by modern urban “folk”, but here Roderick Williams brings out the sophistication of Vaughan Williams’ transcription. The first verse is unaccompanied, as traditional ballad usually was, but the piano part develops it as art song, warmed by the natural sincerity of Williams’ style. A memorable performance. Vaughan Williams collected The Lark in the Morning (1908) in Essex, expurgating more ribald aspects of the original. The Captain’s Apprentice (1908) from a fishing community in Kings Lynn, was adapted into the Norfolk Rhapsody, on which the composer was working at that period.

Holst made sixteen arrangements of folk songs, two of which we have here, The Willow Tree (H83/6 1906-8), and Abroad as I was walking (H83/1). Holst’s Four Songs for Voice and Violin (Op. 35, H132, 1916-17) display a more “modern” sensibility. There are no time signatures. “Bar lines are used for coordination purposes, but the length of each bar varies freely according to the melodic line”, as stated in the uncredited programme notes. Two settings of Walt Whitman’s texts from Whispers of Heavenly Death form the basis of the songs Darest Thou Now O Soul. Holst’s version H72, 1904-5) is declamatory, delivered here with dramatic flair by Roderick Williams. Vaughan Williams’ version, which he was working on at the same period, incorporated the text into A Sea Symphony. Here it is heard in a setting for solo voice and piano, from 1925. The unison version for voices and string orchestra – a hymn with chamber orchestra – can be heard on Martyn Brabbins’ recent recording of A Sea Symphony. (Please read more about that here).

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Time-and-Space.png image_description=Time and Space: Songs by Holst and Vaughan Williams product=yes product_title=Time and Space: Songs by Holst and Vaughan Williams. product_by=Mary Bevan (soprano), Roderick Williams (baritone), William Vann (piano), Jack Liebeck (violin) product_id=Albion ALBCD038 [CD] price=$17.13 product_url=https://amzn.to/2BZLaTMOctober 28, 2019

Wexford Festival Opera 2019

Artistic Director David Agler is presenting his fifteenth, and final, Festival Programme – one which offers Wexford audiences their first Baroque opera since the Festival’s 1985 production of Handel’s Ariodante. Artistic Director Designate Rosetta Cucchi first came to Wexford as a member of the music staff in 1995, has been Agler’s Associate Director since 2005, and has directed many WFO productions including Francesco Cilèa’s L’Arlesiana (in 2012) Mariotte’s Salomé (in 2014) and Alfano’s Risurrezione (in 2017).

During an animated press conference, Cucchi introduced her programme for WFO 2020 and set out her plans for the future, which include ‘themed’ programming, four late-night Cabaret des Artistes performances, WFO 2.0 - a series of free pop-up, multi-disciplinary performances featuring music, drama, singing and dance which will be performed in non-traditional settings in various locations around Wexford town - and, perhaps most significantly, the establishment of the Wexford Factory, a new intensive academy which will offer professional and financial support to fifteen young Irish or Irish-based singers in the early stages of their careers. Cucchi will be the eighth Artistic Director of the Festival, and on 1st November she will present this year’s Tom Walsh Lecture alongside Elaine Padmore, who was the Festival’s fifth Artistic Director, from 1982-94.

And so, what of this year’s operatic offerings? Well, the first production that I saw during this Festival was borrowed from La Fenice in Venice, where it was presented earlier this year, with several members of the cast reprising their roles here. Antonio Vivaldi’s three-act melodramma eroico pastorale, Dorilla in Tempe, was first performed on 9th November 1726 in Venice’s Teatro San Angelo and in several ways exemplifies the mores and practices of Baroque opera. Antonio Maria Lucchini’s libretto mixes pastoral and heroic elements in presenting its ‘X loves Y, who desires Z etc.’ plot.

Manuela Custer (Dorilla), Véronique Valdès (Nomio) and Marco Bussi (Admeto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Manuela Custer (Dorilla), Véronique Valdès (Nomio) and Marco Bussi (Admeto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Thus, Apollo, who is disguised as the shepherd Nomio, has fallen in love with Dorilla, daughter of Admeto, King of Thessaly. She, however, is in love with the shepherd Elmiro. When the valley of Tempe is threatened by a sea-serpent, Admeto is compelled to offer Dorilla as a human sacrifice, but she is rescued by Nomio who claims her hand in marriage as his reward. Elmiro and Dorilla flee; Filindo sets out to find them, hoping that his deeds will win the heart of Dorilla’s sister, Eudamia, who also loves Elmiro. In fact, it is Nomio who captures the fugitives and resolves the conflicts, first saving Dorilla from waters into which she throws herself when Elmiro is condemned to death, and then, as Apollo, restoring harmony through divine intervention.

Structured conventionally as a series of da capo arias with celebratory choral scenes concluding each act, the extant score is in fact something of a patchwork. Dorilla in Tempe was revived several times during Vivaldi’s lifetime, with various alterations, and the score that survives seems to be that performed during the Carnival season of 1734, when Vivaldi converted the work into a pasticcio, inserting music by his contemporaries (including Hasse and Giacomelli). At least ten arias are not from Vivaldi’s own pen, while the Sinfonia concludes with a version of the composer’s Primavera concerto which, fittingly, evolves into the opera’s opening chorus in praise of spring.

Director Fabio Ceresa and set designer Massimo Checchetto take their cue from this seasonal reference and present the drama against the backdrop of a year’s unfolding cycle. Visually, it’s a feast. We begin with the purity and innocence of springtime: a sparkling white double staircase rises in pristine glory, decked with fecund green and cerise branches, and topped with statues representative of handsome Hellenic heroism. When summer comes, nymphs and shepherds sunbathe languorously in a golden glow. By autumn the trees are at their full height, but their heavy copper boughs hang low in the soft rosy light. Finally comes the stark chill of winter, the icy white garden now bare and unforgiving.

Rosa Bove (Filindo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rosa Bove (Filindo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The well-defined colours of Simon Corder’s lighting design and Giuseppe Palella’s luxurious costumes, and the extravagance of whole design, remind us how important the visual dimension of Dorilla in Tempe would have been in 1726, when the audience enjoyed Antonio Mauro’s elaborate sets and danced choruses choreographed by Giovanni Galletto. Here, the feats of Vivaldi’s contemporary engineers are matched by the slithering menace of the Chinese-dragon sea-snake; the giant tree-trunks that surge upwards more swiftly and slickly than Jack’s beanstalk; the beautiful stag-masked dancers who recreate the balletic triumph of the hunt, to the accompaniment of the horns’ stirring flourishes.

Josè Maria Lo Monaco (Elmiro). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Josè Maria Lo Monaco (Elmiro). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

The dramatic conception is less satisfying, though. Essentially, Ceresa presents an opera of three acts, the constituent parts of which don’t cohere into a convincing whole. In Act 1, Greek Classicism provides an opportunity for some Carry On capers and campery. Dorilla (Manuela Custer) is a May Queen, her ‘wedding-dress’ sprinkled with spring flowers. Admeto (Marco Bussi) is a spoiled, sulky, tantrum-prone tyrant, encumbered with an emerald train so long that he must gather it up like a babe-in-arms in order to assert his authority, and more interested in stuffing himself with sugary swiss roll sweet-treats than saving his subjects from the marauding Python (Pitone). Faces are often covered (why the surgeons’ masks for the chorus - is the valley of Tempe less than temperate?); legs and midriffs are frequently bare. As the gold lamé boots, silver hot-pants, John Lennon sunglasses and floral effusions piled up, I felt as if I’d been gorging on Admeto’s candied cup-cakes.

Marco Bussi (Ademto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Marco Bussi (Ademto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

While some gentle mockery of the gods might be apt and advantageous - offering subtle pastoral irony to soften the dramatic heroics - Ceresa’s histrionics run counter to the sincerity of Vivaldi’s music. Surely when Elmiro (an ardent Josè Maria Lo Monaco) defies Admeto and Eudamia, and insists on the integrity of his love for Dorilla, we should believe and admire him? So why are his avowals treated as a joke, mocked by a parade of exploding parasols?

Similarly, when Filindo (an impetuous and impassioned Rosa Bove) declares his intent to track down the errant lovers, why are his preparations - the cleaning of his rifle barrel - interrupted by a paper bird on the end of a pole which dangles, distracts and diverts from the sentiments of his aria? Time and again, arias are disrespected in this way: when Eudamia (whose haughty presumptuousness was well communicated by Laura Margaret Smith) issues her challenge to the smitten Filindo, she - or at least, her gown - is transformed into a sea cave, equipped with treacherous waves and struggling boats - into which Filindo is himself drawn (to drown in the service of love?).

Laura Margaret Smith (Eudamia) and Rosa Bove (Filindo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Laura Margaret Smith (Eudamia) and Rosa Bove (Filindo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Then, in Act 2, things quieten down (and lose momentum as the da capos accumulate), while in Act 3 they turn decidedly nasty. When Nomio returns with the fugitive lovers, Admeto orders that Elmiro be executed. Nomio’s subsequent aria has a grisly backdrop: a dancer is hung upside-down by his ankles and his ‘skin’ flayed, as the blood-red glare deepens. Presumably this is a reference to the slaying of Marsyas, who had the gall to challenge Apollo, played his flute abominably, and whose punishment was to be stripped of his skin (which was destined for a wine-sack) in a cave near Celaenae? Nomio/Apollo as vindictive victor?

Véronique Valdès (Nomio/Apollo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Véronique Valdès (Nomio/Apollo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

All credit to Véronique Valdès for her vocal virtuosity which competed admirably with such visual diversions. While the cast were entirely comfortable with Vivaldi’s elaborate vocal demands, Valdès was the most compelling among them, her tone full and dark - her delivery robust and agile. Ironically, this Nomio was convincingly ‘human’. Bass Marco Bussi was much more persuasive in magisterial mode in Act 3 than as the King of Camp at the opening. Manuela Custer’s Dorilla was a cool-headed maiden, singing with purity and intensity. Fortunately, we had an opportunity to enjoy the full range of Custer’s expressive arsenal - a strong chest voice, superb control of phrasing and dynamics, pliancy of line and beautiful vocal tone - in an imaginatively programmed recital of Italian song, which took us on a journey through her homeland, in St Iberius Church two days later.

Conductor Andrea Marchiol encouraged the Orchestra of Wexford Festival Opera to play with vigour and dramatic punch, and they obliged, but at times the orchestral fabric felt a little too heavy for voices already working hard to surmount Vivaldi’s virtuosic challenges.

If one may have doubts about the staging, then Ceresa’s production certainly convinces one of the merits of Vivaldi’s score - whatever the provenance of its constituent parts - which complements the range of dramatic moods explored, from melancholy to rage, despair to triumph. The final apotheosis of Apollo - a golden god whose magnanimity bathes the mortals in its glorious gleam - was a satisfying conclusion to what was a rather bombastic Baroque burlesque.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

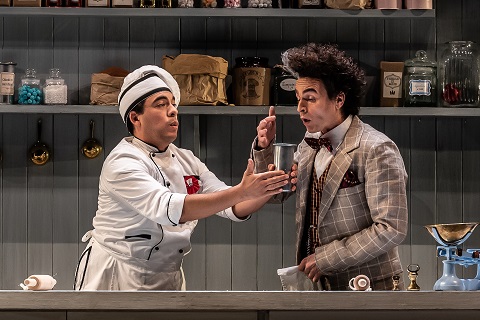

The following evening, there was more visual extravagance: in the form of the three-tier wedding cake that forms the centrepiece of Tiziano Santi’s designs for Rosetta Cucchi’s production of Rossini’s Adina, a confectionary explosion which is complemented by the coloristic extravagance of Claudia Pernigotti’s costumes. This was another ‘import’, first seen in Pesaro in 2018. Here, Adina was preceded by a new work by Andrew Synnott, La cucina - a work designed less as a companion to Rossina’s one-act farce, and more as an explanatory preface to Cucchi’s hyperactive production.

Emmanuel Franco (Camillo Aiuto cuoco) and Luca Nucera (Alberto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Emmanuel Franco (Camillo Aiuto cuoco) and Luca Nucera (Alberto). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Cucchi, who wrote the Italian libretto for La cucina, explains that ‘La cucina serves a very specific purpose: it is a short prelude leading gently to the comic drama of Adina’ and that she and Synnott ‘worked hard to establish a very different mood from Adina’s’. Whereas Adina is a ‘dream’ - a ‘party of the mind’ - La cucina is ‘set in a very mundane world where disappointment, failure and setbacks are always around the corner’. Well, okay, but both are marked by Cucchi’s restless creativity which refuses to let score, text or action speak for itself.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

La cucina is essentially the story of the cake: the one that must be dished up to satisfy Alberto - the famous chef, who has been left mute and traumatised by a Bake Off soggy-bottom disaster at La Scala - and the one that, in Adina, serves as a ground-floor Caliph’s bathroom, and a first-floor boudoir for Adina as she awaits her marriage to the Caliph, and a second-floor prison for Adina’s beloved Selimo. And, which is topped by live ‘Ken and Barbie’ avatars who add to the roster of ‘extras’ Cucchi deems necessary to tell Rossini’s tale.

Máire Flavin (Bianca). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Máire Flavin (Bianca). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Synnott writes sympathetically for voices (as evidenced by his Short Work based on two tales from Joyce’s Dubliners, presented at the 2017 Festival), and his culinary caper is neatly devised and executed. Bianca (a superb Máire Flavin, who whizzes through the kitchen whirlwinds and relishes her more sombre reflections), assistant to Michelin-starred Alberto (Luca Nucera), is teaching a newcomer to the kitchen (Emmanuel Franco – whose lunchtime recital suggested, rightly, that while his baritone is a little wayward at times, he has a keen feeling for dramatic opportunity and an agile, responsive voice) the rites of professional perfectionism. Flour is flourished, dropped and mopped; deliveries don’t appear. The patience of Alberto’s put-upon staff runs out and they flounce off. Alberto has an epiphany: his ‘special ingredient’ is redundant and his power of speech restored. The kitchen personnel are eventually reconciled, and the cake is confected – just in time to take pride of place in the ensuing Adina. Whether Synnott’s opera will find a suitable occasion when it might be revived is another matter.

Sheldon Baxter, Manuel Amati, Máire Flavin and Emmanuel Franco. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Sheldon Baxter, Manuel Amati, Máire Flavin and Emmanuel Franco. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

In a programme article, Cucchi explains that while devising her production of Adina she was ‘deeply inspired by the whimsical worlds of Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland and Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel’. The semiseria libretto makes reference to only five characters, but Cucchi includes so many others - gardeners, cooks, marching bandsmen, ‘men in black’ wielding plastic rifles, two mini-Adina maids - that I half expected the White Rabbit to race through the harem or the Red Queen to strut in and order heads to be whipped off. Farce requires a certain simplicity and neatness, but here Cucchi offers superfluous personnel, ceaseless busyness and unnecessary complication.

Manuel Amati (Alì) and Daniele Antonangeli (La Caliph). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Manuel Amati (Alì) and Daniele Antonangeli (La Caliph). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Adina is enslaved by a Caliph who, astonished by her resemblance to his first love, Zora, urges her to marry him, while respecting her personal feelings (four decades after Mozart’s Seraglio, Rossini thus presents a more light-hearted version of contemporary orientalism). Adina, believing that her beloved Selimo is dead, reluctantly agrees to be his bride. But, of course, Selimo is very much alive, and trying to wangle his way into the harem. With the aid of the gardener, Mustafà, Selimo and Adina are reunited, but their plot to elope is discovered by the Caliph’s close friend, Alì. With Selimo under threat of death, a portrait concealed in a necklace reveals Adina to be Zora’s, and thus the Caliph’s, daughter. A happy ending thus ensues.

Rachel Kelly (Adina). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rachel Kelly (Adina). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Irish mezzo-soprano Rachel Kelly was a fine Adina. Lisette Oropesa made her Pesaro debut in Cucchi’s 2018 production (Oropesa will sing in concert with the WFO Orchestra at next year’s Festival), and this was also the role in which Joyce DiDonato first appeared at Pesaro, in 2003. But, Kelly was, rightly, in no way daunted or overshadowed by these illustrious forbears, and her clear, crisp mezzo made a strong impression, even though the tessitura of the role is fairly low. Vibrato was used sparingly but expressively, emphasising Adina’s innocence. Kelly competed gamely with some dangling strawberries in Adina’s most familiar aria, the ‘Strawberry cavatina’, and with Cucchi’s ‘extras’ elsewhere.

Italian tenor Manuel Amati employed his firm and focused tenor effectively, as the eunuch, Alì, while Emmanuel Franco once again displayed a strong stage presence as Mustafà. Daniele Antonangeli was a magisterial Caliph, the Italian’s dark, handsome bass-baritone suggesting that Adina’s romantic choice was not as simple as it might seem. South African Levy Sekgapane’s deliciously seductive tenor stole the show, for this listener. As Selimo, his Italian diction may have been in need a bit of work, but Sekgapane rose gloriously to Rossini’s rapturous high-flying lines and his tenor delighted with its soft sweetness. Many in the O’Reilly Theatre evidently enjoyed Cucchi’s production very much, though I found it over-populated and rather out-dated in manner.

Levy Sekgapane (Selimo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Levy Sekgapane (Selimo). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Rossini made another appearance during the Festival, at Clayton Whites Hotel, in the form of one of this year’s Short Works. L’inganno felice (The fortunate deception) was composed for the San Moisè Theatre in Venice in 1812 (along with Adina, La Cambiale di Matrimonio, Il Signor Bruschino and La Scala di Seta - it was a busy year for the 20-year-old Rossini). In his Vie de Rossini, Stendhal praised L’inganno felice as a herald of great things to come: ‘Here genius bursts forth from all quarters’. And, we were treated to an excellent staging by director Ella Marchment and designer Luca Dalbosco, whose economical set - a few wooden mine-shaft entrances, tables and stools - deftly conjured the locale and offered opportunities for intrigue.

Peter Brooks (Tarabotto) and Rebecca Hardwick (Isabella). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Peter Brooks (Tarabotto) and Rebecca Hardwick (Isabella). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Marchment demonstrated a sure sense of how to balance the opposing moods of the semiseria plot. Yes, there was an exuberant, erotic dream-escapade during the overture - which was played with a light, crisp touch by pianist/music director Giorgio D’Alonzo - but thereafter all was rooted in reality: a sooty, grimy and briny reality of the sort that communicated the experience of Isabella (Nisa), once betrothed to Duke Bertrando but deceived and betrayed by Ormondo - who hoped to win Isabella for himself - with the aid of his snivelling side-kick Batone. Having been cast adrift on a stormy sea, Isabella was rescued by the kindly Tarabotto, head of the local coal mines, from whom she has kept her identity secret … until, some years later, the Duke comes calling.

Thomas D Hopkinson (Batone) and Henry Grant Kerswell (Ormondo). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Thomas D Hopkinson (Batone) and Henry Grant Kerswell (Ormondo). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

The cast demonstrated vocal and dramatic poise throughout the quick-moving action. Rebecca Hardwick was an assured Isabella, easing through Rossini’s coloratura, demonstrating a sure sense of phrasing, and convincingly balancing melancholy with determination. As Duke Bertrando, tenor Huw Ynyr was forthright of heart and voice. Thomas D Hopkinson, as Batone, coped admirably with the expansive range required and if he was occasionally defeated by Rossini’s fiendish fioritura then this was more than compensated for by his theatrical nous. Peter Brooks’ light baritone was perfect for Tarabotto, Isabella’s saviour, while Henry Grant Kerswell was an imposing Ormondo who, flung down a sealed-up mine at the close, satisfyingly got his comeuppance. Breezing along buoyantly, Marchment’s well-judged production told its touching tale of fidelity rewarded and virtue triumphant most engagingly.

Daydreams and down-to-earth reality were similarly entwined in the other two Short Works presented this year. The eponymous protagonist of Bizet’s Doctor Miracle has nothing to do with the murderous villain who, in The Tales of Hoffmann, persuades Antonia to sing, thereby causing her death. Offenbach is, however, indirectly responsible for Bizet’s second opera which the then 18-year-old Frenchmen wrote in 1857. A competition organised by Offenbach required entrants to compose an operetta to a libretto, Le Docteur Miracle, by Léon Blum and Ludovic Halévy. There were 78 candidates, and first prize was shared by Bizet and Charles Lecocq, the winning entries subsequently being performed, eleven times each, in alternation, at Offenbach’s Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens in April 1857.

Lizzie Holmes (Laurette), Guy Elliott (Pasquin), Simon Mechliński (Mayor) and Kasia Balejko (Véronique). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Lizzie Holmes (Laurette), Guy Elliott (Pasquin), Simon Mechliński (Mayor) and Kasia Balejko (Véronique). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Blum and Halévy’s drama stretches credibility but does show how far the besotted will go in the name of true love. The Mayor’s daughter, Laurette, is in love with Captain Silvio, but her father disapproves and advertises for a servant whom he hopes will protect his daughter from amorous and military advances. Disguised as ‘Pasquin’, courtesy of eye patch and club, Silvio is appointed to the role. He cooks a disgusting omelette for lunch, is promptly sacked, and then sends a note to tell the family they’ve been poisoned by his culinary cock-up. Silvio returns, this time in the guise of Dr Miracle, previously dismissed by the Mayor as a quack, to administer the ‘cure’. So, pleased is the Mayor that he allows the unmasked Silvio to marry his daughter.

If the tale is a trifle, Bizet’s music sparkles. And, Roberto Recchia’s production fizzed along merrily with characteristic wit and satirical style, and the extensive dialogue flowed smoothly. Luca Dalbosco’s straightforward set divided the stage into dining-room and lounge, with a wheel-on ‘kitchen’ providing a focus for the operetta’s musical highlight: the omelette quartet during which - as the salivating diners whipped themselves up in an ecstasy of gustatory anticipation - Guy Elliott’s Pasquin deftly stirred, whisked and seasoned, and delivered the offending outcome to the table.

Guy Elliott (Pasquin) and Lizzie Holmes (Laurette). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Guy Elliott (Pasquin) and Lizzie Holmes (Laurette). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Elliott was a pugilistic Pasquin and relished the physical theatre; he threw himself over sofas and tables with aplomb, and his tenor was no less agile. Simon Mechliński used his eyebrows and voice with equal expressiveness as the patriarch who is outgunned by his womenfolk and servants but who likes to maintain a veneer of imperious command. As Laurette, Lizzie Holmes’s light, lithe soprano was complemented by strong theatrical characterization, while Kasio Balejko’s warm, plump mezzo made her an excellent foil as Laurette’s stepmother, Véronique - painting her nails during her adopted charge’s melancholic romanza, her hugs heaving with insincerity. Doctor Miracle may be slight, but it was slickly delivered here; an amusette and operatic amuse bouche far more appetizing that Pasquin’s poisonous pancake.

Rachel Goode (Maguelonne), Cecilia Gaetani (Armelinde), Isolde Roxby (Marie) and Richard Shaffrey (Le Prince Charmant). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Rachel Goode (Maguelonne), Cecilia Gaetani (Armelinde), Isolde Roxby (Marie) and Richard Shaffrey (Le Prince Charmant). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Davide Garattini Raimondi’s production of Pauline Viardot’s Cendrillon, first seen in April 1904 in the Salon of Mademoiselle de Nogueiras, a former pupil of Viardot, was not quite so convincing, principally because Luca Dalbosco’s set - piled up boxes, trunks and up-turned cobwebby lampshades in the (abandoned/dilapidated?) Hotel Viardot - seemed an unlikely domestic locale for Le Baron de Pictordu - the grocery boy made good who now lives a life of wealthy inertia and idleness. Plastic sheets, slightly torn and grubby, and hung across the length of the platform, marked a shift to the ‘palace’ of Prince Charmant - though as Marie/Cendrillon gleefully flung first pumpkin then mousetrap over her shoulder and beyond the sheets, Johann Fitzpatrick’s illuminated silhouettes deftly signalled a magical transformation to gilded coach and footmen.

Mark Bonney (Le Comte Barigoule) and Ben Watkins (Le Baron de Pictordu). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Mark Bonney (Le Comte Barigoule) and Ben Watkins (Le Baron de Pictordu). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Viardot came from a family of singers - her father was Manuel Garcia Senior, the Spanish tenor for whom Rossini composed the role of Count Almaviva, her older sister was Maria Malibran - and so it’s no surprise that she gives her cast some elegant and eloquent music to sing. Isolde Roxby was a wonderfully ‘genuine’ Cendrillon, delivering the sung and spoken text assuredly, with thoughtful interpretative gestures and a beguiling sweetness of character and tone. As her ghastly, grasping sisters, Cecilia Gaetani (Armelinde) and Rachel Goode (Maguelonne) were garbed in suitable garish red-and-green frocks and sang with glamorous gusto and vibrancy. Mark Bonney enjoyed his ‘prince-for-a-day’ sojourn, singing with pleasing tone and dramatic conviction, while Richard Shaffey’s Prince was indeed charming. Ben Watkins’ Baron was no mere caricature, some subtle vocal inflections adding a sharper, spicier edge.

Cinders’ Fairy Godmother - here, a real estate agent, whose quill served both to record the hotel inventory and to raise the spirit of magic - was sung by Kelli-Ann Masterson from Gorey, a recipient, alongside tenor Andrew Masterson from Omagh, of the PwC Wexford Festival Opera 2019 Emerging Young Artist Bursary Award. Masterson’s soprano gleamed with a cool transparency matched by the Fée’s self-composed manner when instructing and guiding her charge.

Kelli-Ann Masterson (La Fée). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Kelli-Ann Masterson (La Fée). Photo credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Rodula Gaitanou’s production of Massenet’s Don Quichotte opened this year’s Festival, on 22nd October, but I saw the second performance in the run - and I was glad that I had, as this enabled me to enjoy the lunchtime recital presented in St Iberius Church by Georgian bass Goderdzi Janelidze (when he was accompanied by WFO’s Head of Music Staff, Andrea Grant) before I heard Janelidze embody Cervantes’ aging, noble dreamer in the O’Reilly Theatre. For, while Janelidze’s lunchtime programme perhaps lacked stylistic diversity - his chosen arias from Don Carlos and Simon Boccanegra, songs by Tchaikovsky and Georgian folksongs, alongside Don Quichotte’s Act 5 death-bed apotheosis all leaning towards the serious and melancholic - it offered the listener an opportunity to hear and relish the soft-grained potency of his powerful bass, its lyrical warmth, its mellifluous fluency, its animation where apt, its directness and immediacy.

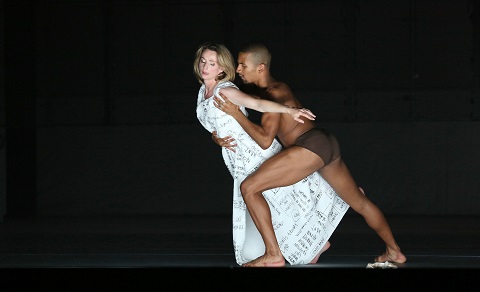

Goderdi Janelidze (Don Quichotte) and Olafur Sigurdarson (Sancho). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Goderdi Janelidze (Don Quichotte) and Olafur Sigurdarson (Sancho). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

And, thus, Janelidze’s performance as Don Quichotte was revealed as a dramatic and expressive tour de force, a remarkable embodiment of nostalgia, nobility and gentility communicated physically and vocally. The ravages of time made their presence felt in Janelidze’s physical frailty: the limbs that needed a gentle nudge to bend or straighten; the slow steps and graceful prod that propelled the gallant knight’s bicycle onwards. Somehow Janelidze had the discipline to restrain his vocal weight - though his projection is so strong that even a whispered phrase made its mark - for the dramatic highpoints which impress upon us the knight’s honour: the riposte to the bandits who attach and abuse him in Act 3, ‘Je suis le chevalier errant’, or his death-bed promise to the loyal Sancho, ‘Prends cette île’. These sudden moments of enrichening and colour were so much more telling for the grave and tender fragility within which they were framed. I was deeply moved, almost to tears, by Janelidze’s courage and conviction.

Goderdi Janelidze (Don Quichotte) and Aigul Akhmetshina (Dulcimée). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Goderdi Janelidze (Don Quichotte) and Aigul Akhmetshina (Dulcimée). Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdason’s Sancho justly received the audience’s warm appreciation too. Sigurdason, loyally following his master on a Vespa, balanced a quasi-Falstaffian pride with sincere service and love. Russian mezzo-soprano Aigul Akhmetshina shone as Dulcinée, her voice creamy and seductive, her dancing joyful and free. Her cruel rejection of Quichotte’s proposal of marriage - a rasping laugh, bordering on vulgarity - was instantly regretted, Dulcinée’s honesty communicated with pathos but not self-pity.

Aigul Akhmetshina (Dulcinée) and Chorus. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Aigul Akhmetshina (Dulcinée) and Chorus. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Gaitanou and designer takis serve up, via the simplest means, a veritable visual banquet of Spanish spirit. Four wooden platforms spin and transform to create a fiesta fairground ruled by the Carmen-esque Dulcinée, furnish the bandits with their hideouts, and taunt Quichotte with ‘giants’. Simon Corder’s lighting is hypnotically enchanting: purple merges with indigo, which slithers into emerald, then blurs into gold, then orange. Henry Grant Kerswell was a crude and callous bandit; Gavan Ring a virile but frustrated suitor of Dulcinée. The Wexford Festival Chorus sang with tremendous heart and spirit, and during the interludes between the acts the Orchestra were given plentiful encouragement to shine by conductor Timothy Myers: there were more superb solos than there is room to mention, but the woodwind rose to the occasion and the cello solo which serves to foreshadow the Don’s demise was beautifully played. This Don Quichotte was a truly memorable way in which to end my visit to Wexford.

Claire Seymour

Bizet: Doctor Miracle (23rd October, Clayton Whites Hotel)

Laurette - Lizzie Holmes, Véronique - Kasia Balejko, Silvio/Pasquin/Dr Miracle - Guy Elliott, The Mayor - Simon Mechliński; Stage Director - Roberto Recchia, Music Director - Andrew Synnott, Stage & Costume Designer - Luca Dalbsoco, Lighting Designer - Johann Fitzpatrick.

Vivaldi: Dorilla in Tempe (23rd October, O’Reilly Theatre, National Opera House)

Dorilla - Manuela Custer, Admeto - Marco Bussi, Nomio/Apollo - Véronique Valdès, Elmiro - Josè Maria Lo Monaco, Filindo - Rosa Bove, Eudamia - Laura Margaret Smith, Ninfe - Rebecca Hardwick/ Lizzie Holmes, Pastori - Meriel Cunningham/Emma Lewis, Dancers; Director - Fabio Ceresa, Conductor - Andrea Marchiol, Set Designer - Massimo Checchetto, Costume Designer - Giuseppe Palella, Lighting Designer - Simon Corder, Assistant Director/Choreographer - Mattia Agatiello, Chorus master - Errol Girdlestone, Orchestra and Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera.

Pauline Viardot: Cendrillon (24th October, Clayton Whites Hotel)

Le Baron de Pictordu - Ben Watkins, Marie (Cendrillon) - Isolde Roxby, Armelinde - Cecilia Gaetani, Maguelonne - Rachel Goode, La Fée - Kelli-Ann Masterson, Le Prince Charmant - Richard Shaffrey, Le Comte Barigoule - Mark Bonney; Stage Director - Davide Garattini Raimondi, Music Director - Jessica Hall, Stage & Costume Designer - Luca Dalbosco, Johann Fitzpatrick - Lighting Designer

Andrew Synnott: La cucina & Rossini: Adina (24th October, O’Reilly Theatre, National Opera House)

Bianca (Sous-chef) (La cucina) - Máire Flavin, Tobia (La cucina)/ Alì (Adina) - Manuel Amati, Camillo (La cucina)/Mustafà (Adina) - Emmanuel Franco, Zeno (La cucina) - Sheldon Baxter, Chef Alberto (La cucina) - Luca Nucera, Adina (Adina) - Rachel Kelly, Selimo (Adina) - Levy Sekgapane, The Caliph (Adina) - Daniele Antonangeli; Director - Rosetta Cucchi, Conductor - Michele Spotti, Set Designer - Tiziano Santi, Costume Designer - Claudia Pernigotti, Lighting Designer - Simon Corder, Assistant Director - Stefania Panighini, Chorus master (Adina) - Errol Girdlestone, Orchestra and Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera.

Rossini: L’inganno felice (25th October 2019, Clayton Whites Hotel)

Isabella - Rebecca Hardwick, Duca Bertrando - Huw Ynyr, Batone - Thomas D Hopkinson, Tarabotto - Peter Brooks, Ormondo - Henry Grant Kerswell; Stage Director - Ella Marchment, Music Director - Giorgio D'alonzo, Stage & Costume Designer - Luca Dalbosco, Lighting Designer - Johann Fitzpatrick

Massenet: Don Quichotte (25th October 2019, O’Reilly Theatre, National Opera House)

La belle Dulcinée - Aigul Akhmetshina, Don Quichotte - Goderdzi Janelidze, Sancho - Olafur Sigurdarson, Juan - Gavan Ring, Pedro - Gabrielle Dundon, Garcias - Elly Hunter Smith, Rodriguez - Dominick Felix, Footman 1 - Thomas Chenhall, Footman 2 - René Bloice-Sanders; Director - Rodula Gaitanou, Set & Costume Designer - takis, Lighting Designer - Simon Corder, Choreographer - Luisa Baldinetti, Chorusmaster - Errol Girdlestone, Orchestra and Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Olafur%20Sigurdarson%2C%20Goderdzi%20Janelidze%20%26%20Aigul%20Akhmetshina%20title%20image.png

image_description=Olafur Sigurdarson, Goderdz Janelidze and Aigul Akhmetshina [Photo credit: Clive Barda]

product=yes

product_title=Massenet: Don Quichotte - Wexford Festival Opera, 25th October 2019

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Olafur Sigurdarson, Goderdz Janelidze and Aigul Akhmetshina

Photo credit: Clive Barda

Cenerentola, jazzed to the max

The production debuted Australia , and is described in the program as follows: “Inspired by the whimsical worlds of Charles Dickens and Tim Burton, director Lindy Hume sets the familiar classic in and around a Victorian emporium filled with period costumes, multi-level sets, and unexpected twists.”

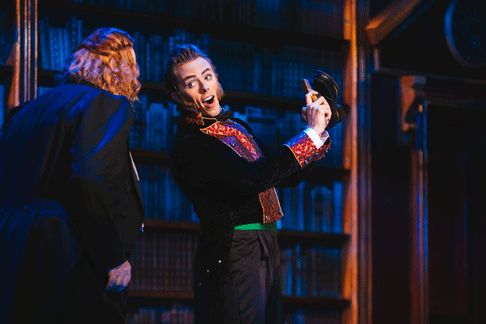

Among the twists are: a scene set in a forced-perspective formal garden in summer when the rest of the show seems to be taking place in the dead of winter; a proscenium-filling wall of bookshelves equipped with a fifty-foot-long hidden bar; a number of primly-aproned and -capped nannies with long luxuriant beards and moustaches; and an origami shopfront stocked with collectible Victoriana.

Oh, the music? It was pretty good (as always depending where you’re sitting; in row T on Sunday evening all the singing seemed dry and distant, while from row P on Saturday afternoon the singers seemed to be in the same room as I. )

This is Gary Thor Wedow’s fifth round in the pit here, but his first conducting Rossini, who presents particular problems of pacing and ensemble, mostly in the composer’s pedal-to-the-metal act-ending accelerations. Here the accelerator seemed in need of a tune-up. Cenerentola was written in two weeks against a deadline, and more of its music feels a little off-the-rack, those careening finales above all.

It also is more dependent for success than most Rossini operas on a single number: the title character’s final (only) aria “Non più mesta” (no more sadness). It’s sort of the coloratura contralto’s “Casta diva”: a summation of what the voice type is technically and emotionally capable of at full stretch.

Neither of the gifted artists singing Angelina here is really a coloratura contralto, each has difficultly producing the frequent very low notes in the role, and each has a personal approach to dealing with the character’s octaves- spanning streams of ornamented melody.

Ginger Costa-Jackson bets the farm on “Non più mesta,” playing Angelina as a bit of a pill, whiny and sulky by turns, making her transformation to radiant butterfly in the last five minutes of the show absolutely stunning.

Her alternate, Wallis Giunta, takes the opposite tack, playing the character as a Disney princess for today, twinkly, spunky, good-humored; think Amy Adams in Enchanted and you’ve got it. Her way with “Non più mesta” is in the same vein; instead of ripping into the roulades she points them slyly, consciously, making us co-conspirators rooting for her, a damsel dancing through a vocal minefield.

Her approach to the role may be why I very much enjoyed the Saturday matinée and left McCaw Hall energized, while Friday’s performance left me feeling a bit pummeled by a staging so extravagantly out of scale with the material. (That and those seats.)

The tenor leads and capable supporting players were all personable. Michele Angelini (of the Brooklyn Angelinis) is the Rossini-tenor version of a Bari-hunk: he has a puckish smile, ease of movement, and technique so fast and fluent that it’s easy to believe the rumor that he has long been the go-to tenor to cover for Juan Diego Flórez. In a way his facility with florid music is a bit of a downside; he makes it seem too easy to be astonishing. But there’s no chemistry between him and Costa-Jackson’s morose Angelina.

Saturday’s Don Ramiro was Matthew Grills. His voice is coarser than Angelini’s, but almost as facile. Most important, he and Giunta “click” at first glance: they’re as sure to end up together as Hepburn and Tracy, Rock and Doris, which in romantic comedy is more important than high-notes any day.

All the rest of the cast perform in both versions of the show except for the character of Dandini, Figaro to the Prince’s Almaviva. Here there’s little to compare between Friday’s Joo Won Kang and Saturday’s Jonathan Michie; Michie’s a born clown, Kang isn’t.

The bad-guy trio of Don Magnifico and his vain, grasping daughters (Peter Kàlmàn, Maya Costa-Jackson, Maya Gour) suffer from this staging’s (and most others) reduction of their characters to completely witless cartoons. Kàlmàn bills himself as a basso buffo, but he’s not a true bass, and his buffoonery is dryly cynical, not really comic.

I would love sometime to see a Cenerentola where Clorinda and Tisbe were permitted to exhibit one trace of human behavior amid the usual enforced gamboling, squalling, and preening, but I’m not expecting to. But Costa-Jackson and Gour have lovely voices; they deserve to be treated as more than wind-up toys.

The remaining character (and the singer performing him) stands apart from the general goofiness and superficiality of this staging. Bass Adam Lau has performed primarily secondary roles at Seattle Opera. But the role of Alcindoro, though small is central to Cenerentola. He’s described in the opera itself as the Prince’s tutor and as a “philosopher.” He also takes the place of the usual fairy-godmother. But he’s not, like her, just a deus-ex-machina. He’s the embodiment of the opera’s alternate title: “La bontà in trionfo”: the triumph of goodness, a gentle Sarastro, a sincere Don Alfonso.

Every time he appears, however clumsy the presentation, he suspends the whirligig motion around him for a few moments of calm, warmth, and good-will. You’d expect it to stop the action cold, and in a way it does; but it leaves us refreshed, better prepared to ride out the turbulent hi-jinx we know will soon be back.

And Lau, though he doesn’t have the resonant bass notes that ground the role, has something more important. A plot device in a greatcoat and top-hat, he’s the most human creature we encounter in the whole show.

A last word: the men’s chorus of Seattle Opera has gotten the reputation in recent stagings (Trovatore, Carmen, Rigoletto) of being the a musical version of The Gang Who Couldn’t Shoot Straight. With the help of choreographer and co-director Daniel Pelzig, they set a new standard forclassy movement and even do some deft dancing along the way. Let’s hear it for the boys.

Roger Downey

Gioachino Rossini: La cenerentola, ossia Bontà in trionfo

Cenerentola/Angelina: Ginger Costa-Jackson (Oct. 19); Wallis Giunta (Oct. 20); Prince Ramiro: Michele Angelini (10/19); Matthew Grills (10/20); Dandini: Jooo Won Kang (10/19); Jonathan Michie (10/20); Don Magnifico: Peter Kàlmàn; Clorina: Miriam Costa -Jackson; Tisbe: Maya Gour; Alidoro: Adam Lau.Production directed by Lindy Hume; production designer: Dan Potra; Lighting: Matthew Marshall; Choreographer and associate director: Daniel Pelzig. Seattle Opera Male Chorus (Chorusmaster John Keene). Member sof the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, Gary Thor Wedow, conductor.

Seattle Opera, Marion McCaw Hall, October 19th and 20th, 2019.

October 26, 2019

Bottesini’s Alì Babà Keeps Them Laughing

For the libretto, Bottesini and Taddei used the text of a French opera by Luigi Cherubini based on the famous story from French orientalist and archaeologist Antoine Galland’s version of The Thousand and One Nights. Taddei translated it into Italian and shortened it considerably. Bottesini premiered the opera in 1871. The 2019 version directed by Foad Faridzadeh was an uproarious comedy set in the 1940s. His clever, wickedly amusing production had the Southwest Opera audience laughing out loud on numerous occasions.

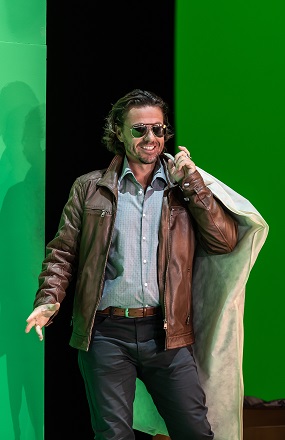

What this opera needed was a star to carry the show, and Opera Southwest presented a perfect answer in the sensational bass-baritone, comic actor and all around showman, Ashraf Seweilam as Alì Babà. He celebrated his character’s riches by dancing nimbly across the stage but cowered in terror when threatened by thieves. His presence filled the stage as his resonant, bronzed tones flowed throughout the National Hispanic Cultural Center’s moderate-sized Journal Theater.

Monica Yunus as Delia, Ashraf Seweilam as Alì Babà, and Christopher Bozeka as her lover, Nadir.

Monica Yunus as Delia, Ashraf Seweilam as Alì Babà, and Christopher Bozeka as her lover, Nadir.

Richard Hogles’ scenery consisted mainly of neon-lit arches crowned by a circle. The back of each scene was a projected wall, building, or cave designed by Media Vision that denoted the area in which the action took place. Daniel Chapman’s lighting created the appropriate ambiance for each setting. Carmella Lynn Lauer’s costumes, colors for female soloists but black and white for everyone else, established the time period as the forties.

Monica Yunus was a sweet, loving Delia who commanded attention as she sang with lustrous tones, an occasional trill, and some surprisingly hefty soprano sonorities. Her tenor was the lyrically gifted Christopher Bozeka whose smooth but warm and hefty legato immediately won the audience over to his side of the argument. They made a delightful young couple and they succeeded in making the audience want them to be together. Laurel Semerdjian was a conniving Morgiana who fascinated onlookers with her hijinks and comic timing. She sang with excellent diction and strong tones.

As the Head of Customs Aboul Hassan, Kevin Thompson had an imposing physique and a voice with a nasal tone that made him a fine villain. It was no wonder that Delia did not want to marry him. One of the most interesting voices in the show belonged to Darren Stokes, the bass-baritone who sang Orsocane (Beardog). While acting a “tough guy” part, he sang with rich, resonant dark tones.

Kevin Thompson as Aboul Hassan and Ashraf Seweilam as Alì Babà with chorus.

Kevin Thompson as Aboul Hassan and Ashraf Seweilam as Alì Babà with chorus.

Three members of the 2019 Opera Southwest Young Artist Program: Matthew Soibelman as the Treasurer, Jonathan Walker-VanKuren as Orsocane’s Adjutant, and Kameron Ghanavati as Alì Babà’s Slave Faor, impressed me with both their vocal abilities and their stagecraft. Chorus Master Aaron Howe’ s women’s ensemble sang with light, mellifluous harmony as they moved across the stage. His men’s group portrayed believable cut-throat thieves and thugs while singing with strong masculine sounds.

Conductor Anthony Barrese put together the score for this production, the first in nearly a century. He gave a rousing, propulsive rendition of this rarely-heard work that allowed the singers enough space to breathe comfortably and interpret their characters, but never let the tension lag. He commanded a fifty-piece orchestra that gave listeners all the tunes and sonorities of this wonderful piece. The composer, who was an orchestra player and conductor, knew how to color the events and situations of this complicated story. Alì Babà was a fabulous evening’s entertainment and I’m glad I traveled to Albuquerque to see it.

Maria Nockin

Cast and Production Information:

Alì Babà, Ashraf Sewailam; Delia, Monica Yunus; Nadir, Christopher Bozeka; Aboul Hassan, Kevin Thompson; Orsocane, Darren Stokes; Morgiana, Laurel Semerdjian. Calaf, Thamar, and Faor, young artist program members: Matthew Soibelman, Jonathan Walker-VanKuren and Kameron Ghanavati. Conductor, Anthony Barrese; Director, Foad Faridzadeh; Costume Designer, Carmella Lynn Lauer; Scenic Designer, Richard Hogle; Lighting Designer, Daniel Chapman; Projection Designer, Media Vision; Chorus Master, Aaron Howe. Journal Theater, National Hispanic Cultural Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico, October 25, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/LWO_191017_33561-Edit-Edit.png image_description=Ashraf Seweilam as Alì Babà [Photo by Todos Juntos] product=yes product_title=Bottesini’s Alì Babà Keeps Them Laughing product_by=A review by Maria Nockin product_id=Above: Ashraf Seweilam as Alì BabàPhotos by Todos Juntos

October 24, 2019

Ovid and Klopstock clash in Jurowski’s Mahler’s ‘Resurrection’

Metamorphosis is the final part of a larger work, Renewal, based on Ovid’s epic poem about myth, creation, transformation, love and deification. But elements of Ovid’s poem have much to do with violence, and this is not a work which wears its tension between art and nature with a cloak of uncertainty about it. Indeed, much of Ovid’s Metamorphosen is entirely in conflict with the natural world – a theme that does sit neatly with some of Mahler’s Wunderhorn symphonies. The problem is, Matthews’s Metamorphosis is the end piece of a larger work and it follows on from a scherzo, Broken Symmetry, of uncommon violence – it’s just none of these Ovidian themes penetrate this particular Matthews piece. Musically, it feels entirely like the ending of one work, and not like the preface to another. Metamorphosis might open on a deep-pedal C, which remains somewhat rooted throughout, just as the first movement of the Mahler opens on C minor – but the hushed, reflective coda with its strangely muted chorus is in direct contrast to the 42 bars of the funeral march with its oppressive lower strings which explodes like a storm at the opening of the Mahler. Simply elided into one another, this wasn’t a natural fit at all.

Jurowski’s approach to Mahler’s Second is refracted through some very cool lenses. This was not a performance which proved notably gripping when it came to the much deeper thought process – there was never much doubt that Jurowski had the sound the London Philharmonic could project in mind than any perceived notion that the decibels had concepts of anger, fear or terror beyond that. It could be thrilling, but you felt you were being short-changed on the expressive range. It’s not as if Mahler doesn’t elaborate his score like a kind of musical Baedeker: when he hints that phrases in the first movement should be likeMeeresstille (‘Calm like the sea’) or that there are marked differences between piano and pianissimo one wants to hear to them. There was little of that on offer here. But the fluidity of Jurowski’s tempo did make a difference in the Andante Moderato where the staccato strings and the pacing of the ländler were quite distinctive. The counterpoint between the strings and the woodwind wasn’t just refined it was mysterious. The Scherzo plunges between dissonant and turbulent surges (typically measured out in oodles of high-powered accents by Jurowski and the LPO) but it’s also a movement that prefaces ‘Urlicht’ and which has complete musical union.