December 31, 2019

Tara Erraught sings Loewe, Mahler and Hamilton Harty at Wigmore Hall

Wigmore Hall was silent for just three days this Christmas before first the Schumann Quartet and then pianist Jonathan Plowright reignited man’s search for ‘the elusiveness of music in its great abstraction’, as represented by Gerald Moira’s cupola above the Wigmore Hall platform. They were followed by Irish mezzo-soprano Tara Erraught in this recital with pianist James Baillieu, in which lieder by Carl Loewe and Gustav Mahler were complemented by Irish songs, both traditional and composed by Hamilton Harty.

Erraught is a calm, self-assured and personable performer. Sadly, the audience at Wigmore Hall was not large but the Irish mezzo-soprano was obviously delighted to be performing at the Hall, and her warmth and ease were communicated throughout the recital. The piano lid was fully raised, and the instrument positioned towards the front of the platform. In the opening few songs, the balance between voice and piano was not always effective, especially when the vocal line lay low, but Erraught quickly got the measure of the acoustic and her clear, fresh mezzo and generally attentive diction communicated the poetic moods and situations effectively.

During his lifetime, Carl Loewe (1796-1869) built up a reputable career as a composer-singer, accompanying himself in public concerts, but his work is not well-known today in comparison with that of his fellow Romantic songsters. His oeuvre includes approximately 250 lieder and 150 art ballads, and Erraught and Baillieu offered us a welcome opportunity to hear eighteen of his songs; if one was inclined to compare them with more familiar settings of these texts by the likes of Schubert, Schumann et al, then Loewe held his ground well, Erraught and Baillieu bringing forth the diverse characters and colours within the sequence.

Of the four songs presented from Gesammelte Lieder, Ges änge, Romanzen und Balladen Op.9, ‘Der du von dem Himmel bist’ (You who come from heaven) was the most engaging. Following segue from ‘Über allen Gipfein’ (Over every mountain-top), it effected a striking change of mood from a hushed calm to a more vibrant, Schumann-esque passion. Before that, Baillieu’s dark, ponderous ambience-setting opening to the ‘Szena from Faust’ had revealed his sensitivity to poetic-dramatic mood and nuance, while Erraught worked hard to convey the extremes of tenderness and pain which Goethe juxtaposes.

Five songs from Loewe’s Liederkreis nach Gedichten von Friedrich R ückert Op.62 followed. Again, the Irish mezzo-soprano communicated the spirit of the text effectively. In ‘Irrlichter’ (Will-o’-the-wisps), the voice hurried and scurried mischievously, sinisterly while the piano’s whispers raced and whirled, but it was in the slower more lyrical songs that Erraught seemed most comfortable. ‘Süsses Begräbnis’ (Loving burial) achieved a beautiful tranquillity, enhanced by the piano’s gentle chromaticisms and fluid oscillations. And, whereas on occasion there was a sense that Erraught was going through the motions of storytelling rather than truly living the protagonists’ dramas, in ‘O süsse Mutter’ (O mother dear), she seemed to engage more fully and freely with the sentiments and experience of the song’s speaker, thereby communicating feeling and situation more directly and persuasively.

The Loewe sequence closed with the composer’s Op.60 cycle of nine songs settings poems from Chamisso’s Frauenliebe, composed in 1836. ‘Seit ich ihn gesehn’ (Since first seeing him) and ‘Du Ring an meinem Finger’ shared a charming simplicity, though the latter blossomed more expansively in the final couplet, while ‘Er, der Herrlichste von allen’ (He, the most wonderful of all) enabled Erraught to exploit her richly coloured lower voice and demonstrate her vocal agility. Baillieu’s characterisation captured the contradictory impulses of the soon-to-be-wed maiden in ‘Helft mir, ihr Schwestern’ (Help me, my sisters); again, Erraught displayed a fine sensitivity to the melodic phrasing in ‘Süsser Freund’ (Sweet friend). Best of all was ‘Nun hast du mir den ersten Schmerz getan’ (Now you have caused me my first pain) in which the bereaved woman’s hurt was communicated with affecting poise, the words fully painted with vocal and harmonic colour as voice and piano octaves captured the extent and volatility of the singer’s grief. To conclude, Erraught exhibited a strong sense of structure and nuance as she took us through the repetitive melodic utterances of ‘Traum der eignen Tage’ (Dream of my own days), the voice carried forward by the piano’s fluency towards a convincing if sombre close when the voice was finally permitted to fall, in grave resolution: “Sei der Schmerz der Liebe/ Dann dein höchstes Gut.” (May love’s sorrow then be your dearest possession.)

We had been informed that three programmed songs from Mahler’s Des Knaben Wunderhorn would not be performed, and so the second half of the recital opened with the composer’s Five R ückert Lieder. During the concert, Erraught reminded us that she has lived in Germany for several years (where since 2010 she has been a resident principal soloist with the Bayerische Staatsoper), and if I did not feel that she was truly ‘inside’ the German texts of the Loewe songs before the interval, now she seemed to find a more ‘natural groove’.

The mezzo-soprano found a nice balance between the intimacy of the songs and their expressive sophistication. After the playful ‘Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder!’ (Do not look into my songs!), in ‘Ich atmet’ einen linden Duft’ (I breathed a gentle fragrance) Erraught’s voiced did indeed seem ‘scented’, floating like the fragrance wafting from the spray of lime, the mood dreamy, the harmonic colour somewhat enigmatic. As the vocal line rose in ‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen’ (I am lost to the world), I wished that we had heard more of Erraught’s upper range, particularly as the bronzed sheen of the soaring phrases made such a striking contrast to the plummet of the final stanza, ‘Ich bin gestorben dem Weltgetümmel,/ Und ruh’ in einem stillen Gebeit’ (I am dead to the world’s tumult, and rest in a quiet realm). Baillieu’s postlude was beautiful, transporting us to the heaven in which the sing lives along, ‘In meinem Lieben, in meinem Lied.’ (In my loving, in my song). ‘Liebst du um Schönheit’ (If you love for beauty) was wonderfully understated and exquisitely controlled, lofting vocal phrases left hanging in ambiguity. ‘Um Mitternacht’ (At midnight) was disturbing, troubled and lonely: though the protagonist finds some solace in his faith in God, the piano’s closing utterance offered little consolation.

Erraught introduced the Irish songs, explaining that while it had once been standard for schoolchildren to learn and sing the traditional songs of their native land, this is now less common and she herself has only a limited knowledge of the repertory. ‘Roísín Dubh’ was intense and imbued with passion and drama: I think I like my Irish folk-songs rather more in the style of Niamh Parsons, but there was no doubting the rhetorical power and heartfelt sentiment of Erraught’s rendition, which was deepened by the piano’s shuddering dark tremolos in the final verse. ‘The lark in the clear air’ was cleansing and pure; simply and assuredly beautiful singing.

Two songs by Hamilton Harty brought the recital to a close. ‘Sea Wrack’ has the poetic and musical depth of a genuine lieder, and Erraught and Baillieu made much of the linguistic pun ‘wrack’/’wreck’ - the former being both a type of seaweed and an archaic Irish word for a shipwreck - though they never lapsed into melodrama as the sea-weed collector’s old brown boat went down ‘upon the Moyle’. The burbling piano gestures of the closing lines were eerie: ‘The dark wrack,/ The sea wrack,/ The wrack may drift ashore.’

Erraught and Baillieu obviously enjoyed each other’s musical company, and the small but appreciative Wigmore Hall audience were undoubted delighted that they had shared in the evening’s music-making.

Claire Seymour

Tara Erraught (mezzo-soprano), James Baillieu (piano)

Carl Loewe : From Gesammelte Lieder, Gesänge, Romanzen und Balladem Op.9 - ‘Meine Ruh ist hin’, ‘Ach neige, du Schmerzensreiche’, Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh’ (Wandrers Nachtlied) and ‘Der du von dem Himmel bist (Wandrers Nachtlied II)’; From Liederkreis nach Gedichten von Friedric Rückert Op.62 - ‘Irrlichter’, ‘Hinkende Jamben’, ‘Das Pfarrjüngferchen’, ‘Süsses Begräbnis’ and ‘O süsse Mutter’; Frauenliebe Op.60; Gustav Mahler: Five Rückert Lieder; Trad/Irish: ‘Róisín Dubh’ and ‘The Lark in the Clear Air’; Hamilton Harty: ‘Lane o' the Thrushes’, ‘Sea Wrack'

Wigmore Hall, London; Sunday 29th December 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Tara%20Erraught%202019.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Tara Erraught (mezzo-soprano) and James Baillieu (piano) at Wigmore Hall, 29th December 2019 product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Tara ErraughtBach’s Christmas Oratorio with the Thomanerchor and Gewandhausorchester Leipzig

Performed by the Leipzig Thomanerchor and the Gewandhaus Orchestra it brings together two of the city’s most venerable musical institutions, under the baton of Gotthold Schwarz - the seventeenth Thomaskantor to have held that position since Bach’s own tenure from 1723 until his death in 1750. Schwarz was inaugurated as Thomaskantor on 20th August 2016. The sacred music of Bach forms the core of the choir’s repertory, and each week they are joined in St Thomas’s Church by members of the Gewandhausorchester for performances of Bach’s cantatas, continuing a collaboration which began at least as early as 1835 when Felix Mendelssohn, as Music Director, programmed Bach’s music.

This Accentus recording disc is not the first time that we been treated to Bach from the ‘home team’. In 2012, Georg Christoph Biller (Kantor from 1992 to 2015) conducted the same forces (with soloists Martin Petzold (Evangelist), Paul Bernewitz and Friedrich Praetorius (treble), Ingeborg Danz (alto), Christoph Genz (tenor), and Panajotis Iconomou (bass)) for the German label, Rondeau . But, Schwarz’s account of the Christmas Oratorio is certainly a compelling one.

In the CD liner booklet, Katharina Rosenkranz raises the question of ‘whether [the Christmas Oratorio] is an oratorio in the real sense of the word’, since ‘the work consists of six separate cantatas that were intended for different Sundays and holidays during the Christmas festivities of the year in which they were composed’. But, though the cantatas - Bach’s last major contribution to the repertoire of German Lutheran liturgical music - were first heard in 1734/35 in Leipzig’s two main churches, St Thomas and St Nicolas, over twelve days, it does not seem fair to suggest that the work lacks a continuous biblical narrative. Bach would surely have been familiar with Passion settings the parts of which were intended or adapted for presentation on separate days over Holy Week or Lent. And, his title specifies ‘Oratorium’, denoting a tradition of gospel narration through the voice of an Evangelist and various interlocutors, such as is represented by his own Passion settings. He titled each cantata a ‘part’, suggesting that while it might stand on its own terms it forms part of a larger whole.

Moreover, Rosenkranz asserts that, unlike the Passion narrative, the ‘biblical narrative of the events surrounding the birth of Jesus contains little dramatic potential’. I’m not sure that Handel would have agreed, not that Gospel writers were averse to indulging in narrative gestures of a deliberately dramatic nature. But, I think the point being made is that these are meditative cantatas. Rosenkranz offers a summary of each cantata (presented in German, English and French), not just identifying key narrative and musical features, but also the juxtaposition which is the ‘essence’ of each cantata: lowliness and majesty in the first, man and god in the third, for example. Whatever the spiritual message, though, for this listener it is the sheer vibrancy, colour and energy of the singing and playing here that is most absorbing and exciting.

The opening chorus “Jauchzet, frohlocket” - kick-started by exultant timpani, sharply etched trumpets flourishes and rejoicing, racing flutes, oboes and strings - is brilliantly colourful, and the individual instrumental lines retain their fine definition with the entry of the warm and heart-stirring choral ensemble. Bach’s music was originally written for the opening movement of Cantata BWV 214, which begins, “Tönet, ihr Pauken! Erschauet, Trompeten, Klingende Saiten, erfüllet die Luft!” (Sound, ye drums now! Resound, ye trumpets! Resonant strings fill the air!) and the choric instructions are as just as apt and satisfyingly fulfilled here. The bright tone of the trumpets and robust strike of the timpani are vivid presences throughout the sequence; horns and oboes add terrific pungency and punch to the opening chorus of Part IV, “Fallt mit Danken”, which are balanced by the sumptuousness of the choral ensemble and the litheness of the vocal lines. But, there are instrumental episodes of touching affection and stillness too. The theme of the Sinfonia which opens Part II may originally have embodied the enticements of the disreputable ‘Wollust’ who tempts Hercules in the secular Cantata BWV 213, but the gentle lilt of flute and oboe in dialogue with strings is no less effective or enchanting a lullaby for the infant Jesus, one which Schwarz paces fluently and which captures the spirit of pastoral joy and ease.

Patrick Grahl has a fairly light tenor, but it is an expressive voice and the appealing tone engages and consoles the listener. Grahl rises to the peaks of the Evangelist’s recitatives cleanly and comfortably. Accurate and nuanced, the sometimes twisting, angular lines are focused and well-tuned, and the declamation is heightened or quietened as is appropriate.

Markus Schäfer sings the tenor arias with greater intensity of colour and urgency, at times bringing an almost operatic ‘drama’ to the unfolding action. Schäfer demonstrates fine nimbleness in the running lines of “Frohe Hirten, eilt, ach eilet” in Part II, and the aria is sweetened by the traverse flute solo which has the purity of an angel’s cry. I particularly enjoyed “Ich will nur dir zu Ehren leben” in Part IV, in which the two solo violins strive forward in ever-inventive dialogue and Schäfer’s energy, accuracy and focus never flag, creating a compulsive sweep which draws in the listener. It’s no surprise that towards the end of the aria the double bass joins in, too, with vigour and heartiness: the aria has a powerfully communicative ‘human’ quality.

In the many arias for alto, Elvira Bill makes a very strong impression. In Part 1, the relaxed clarity of the vocal line in “Nun wird mein liebster Bräutigam” is beautifully complemented by the reedy fluidity of the oboe d’amore and the fullness of the low, light-footed continuo - light and shade, as it were: the aria seems literally to shine with light and grace. The sweet tone and unaffected sustained notes at the start of “Schlafe, mein Liebster, genieße der Ruh” in Part II bear no hint of the afore-mentioned Wollust’s sinister entreaties: here, Schwarz again shows good judgement of the tempo and there is both decorous vocal ornamentation and lovely playing by the oboes d’amore and da caccia, with gentle string doubling. One of the highlights of the sequence is Part III’s “Schließe, mein Herze, dies selige Wunder” in which a deeply expressive violin solo is complemented by sensitive organ and cello continuo; here, Bill’s plea, “Enclose, my heart, these blessed miracles fast within your faith!”, is unmannered and truly affecting, combining wonder, passion and peace. The text is conveyed with similar expressive impact in the recitative at the end of Part V, “Wo ist der neugeborne König der Jüden?” (How bright, how clear must your radiance be, Beloved Jesus!), which shines with joy.

Bass Klaus Häger puts much feeling into the words and his recitatives are powerful. I found Häger a little under-powered and lacking in brightness of tone in comparison to the trumpet solo in “Großer Herr, o starker König” in Part I, but his recitative at the start of Part IV is arresting: “Immanuel, o süßes Wort!” (Emmanuel, O sweet word!). And, in Part V the long, and sometimes quite high, lines of the bass aria, “Erleucht auch meine finistre Sinnen”, allow the lightness and lyricism of his bass to make their mark, aided by a fine obbligato oboe solo. The alternating groupings and colours of the duet for bass and soprano in Part III, “Herr, dein Mitleid, dein Erbarmen”, are well-crafted by Schwarz, with the organ switching between roles - first a voice in the counterpoint, then providing foundation steps - and soprano Dorothee Mields exhibiting a purity and cleanness of tone to complement Häger’s more grainy bass.

Mields provides another of the recording’s highlights, “Flößt, mein Heiland, flößt dein Namen” in Part IV, where her silky soprano is exquisitely embroidered by the echoes of the solo oboe and chorister Clemens Sommerfeld, and Thomasorganist Ullrich Böhme makes a very expressive contribution. The light staccato of the continuo bass in Part VI’s “Nur ein Wink von seinen Händen” is a perfect foundation for the airy syncopated twists and turns above of soprano, oboe d’amore and violin, as Mields asserts God’s unassailable power. The questions and exclamations of the soprano, alto and tenor soloists, with violin obbligato, in the Part V trio, “Ach, wenn wird die Zeit erscheinen?”, are urgent and dramatic. This is superb music-making: listening, I found myself smiling and reflecting that Bach doesn’t come much better than this.

The chorales are solid and warm, with the gutsy boys’ voices resplendent at the top: Schwarz, and the Accentus engineers, achieve a good balance between the choir, the doubling instruments and the organ. The majesty of “Ach mein herzliebes Jesulein”, which closes Part 1, as the choir alternates with stirring trumpets and timpani, conveys certainty and conviction. “Brich an, o schönes Morgenlicht” in Part II is brisk and forthright, but Schwarz effects a well-modulated slowing and diminution at the close. The boys’ voices often add vigour to the choruses as in “Herrscher des Himmels, erhöre das Lallen” in Part III where, alongside trumpets, timpani and bass, the trebles’ energised lines strive upwards, surging with an optimism which blossoms in the contrapuntal dynamism of “Lasset uns nun gehen gen Bethlehem und die Geschichte”.

Schwarz’s inclination is to keep the chorales moving; fermatas are observed with a light touch and the resulting momentum is often most effective, as in “Dein Glanz all Finsternis verzehrt” in Part V, where the repetition of the first vocal phrase runs on into the final phrase, thereby observing the elision in the text and establishing the certainty of salvation: ‘Doch, sobald dein Gnadenstrahl/ In denselben nur wird blinken, Wird es voller Sonnen dünken.’ (Yet, as soon as the rays of your mercy/ Only gleam within there/ It will seem filled with sunlight.)

‘Wir singen dir in deinem Heer/ aus aller Kraft, Lob, Preis und Ehr’ (We sing to you in your host with all our might: “Praise, honour and glory”) proclaims the chorale which closes Part II. And, sing and play with all their might, and insight, the Thomanerchor and Gewandhaus Orchestra certainly do. This recording has been a welcome festive companion for this listener, but it will bring much pleasure at any time of the year.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bach%20Thomanerchor%20Leipzig%20Gewandhaus%20Orchester.jpg image_description=Accentus ACC 30469 product=yes product_title=J.S. Bach: Christmas Oratorio BWV 248 product_by=Thomanerchor Leipzig, Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Gotthold Schwarz (conductor), Dorothee Mields (soprano), Elvira Bill (alto), Patrick Grahl (tenor, Evangelist), Markus Schäfer (tenor), Klaus Häger (bass) product_id=Accentus ACC 30469 [CD] price=$29.38 product_url=https://amzn.to/2F5pWVUDecember 29, 2019

Retrospect Opera's new recording of Ethel Smyth's Fête Galante

First, he quoted Smyth herself, ‘“in this country the only necessaries of life recognised by our rate-payers are things like drains and water-supply”’, continuing: ‘a second, much less debatable, is that the composer was so indiscreet as to be a woman, and to start composing at a time when the claims of women as creative artists were conceded in literature alone.’ Bennett went on to suggest that Smyth was ahead of her time, ‘since the English are only just emerging from the stage when they preferred their cooks and composers to be foreign, and distrusted any of their countrymen - or women - who attempted anything more solemn than Sullivan’. Finally, he suggested that her preferred genre fuelled further condemnation: ‘most important of all, is that her chief ambition was operatic at a time when England showed even less than the present signs of being addicted to music drama.’

Born in London in 1858, the daughter of one General J.H. Smyth, who did not find his daughter’s determination to pursue a career as a composer either agreeable or appropriate, Smyth travelled in 1877 to study at the Leipzig Conservatoire, and it was in Germany that her early works were favourably received during the 1880s. While she did struggle to get her music heard in England (Robert H. Hull, writing in the September 1930 edition of The English Review in September 1930, blamed ‘vested interests’), she was not without supporters. It’s interesting, though, that even those such as Hull, who set out to present an impartial assessment of Smyth’s work - explicitly rejecting the ‘illogical bias’ and adoption of a ‘concessive standard of values’ by those estimating the achievement of women composers - and who praised operas such as The Wreckers (1902-04) and The Boatswain’s Mate which exhibit ‘the true worth and independence of her thought’, was not able to avoid terms redolent of ‘masculine virtues’, observing the ‘virile characteristics’ and ‘sturdy, forthright’ nature of Smyth’s musical language.

Hull proposed that Smyth’s short opera, or Dance-Dream, Fête Galante (1921-22) marked a significant ‘development in the composer’s harmonic style, and reveals afresh a capacity for sensitive treatment’, concluding that: ‘Ethel Smyth’s genius, by reason of its power and sincerity, contributes strikingly to the music of our time.’ First performed on 4th June 1923 at Birmingham Repertory Theatre, by Thomas Beecham’s recently formed British National Opera Company, Fête Galante was composed during a difficult period when Smyth had begun to lose her hearing; but 1922 was also the year in which she was awarded a DBE for services to music. The opera was well-received: it was seen again a week after the premiere, at Covent Garden, and presented two years later at the Royal College of Music alongside Smyth’s final opera, Entente Cordiale.

All credit, then, to Retrospect Opera, for attempting to remedy the subsequent neglect of Fête Galante with this recording, the company’s seventh release, which follows their issue of The Boatswain’s Mate and the re-release of conductor Odaline de la Martinez’s recording of The Wreckers , which received its first modern professional performance under de la Martinez’s direction at the BBC Proms in 1994.

The libretto of Fête Galante is based upon a short story from a collection by Smyth’s friend, Maurice Baring, Orpheus in Mayfair (1909), the versification of the dramatized version of the tale having been undertaken by the poet Edward Shanks. At first glance the spirit of commedia dell’arte seems evident: the cast list comprises a Columbine, Pierrot and Harlequin, alongside a King and Queen, and a Lover. But, if the title of Smyth’s opera translates literally as ‘elegant party’, then its dramatic reality is altogether more complex and sinister. The commedia’s perennial themes of mistaken identity and jealousy do indeed loom large, but here they take a macabre and uncanny turn. The Queen’s banished Lover returns in a double-disguise - a black cloak masks the Pierrot costume he has donned - and their garden tryst is overseen by both the ‘real’ Pierrot and the latter’s smitten admirer, Columbine. Believing that she has been betrayed, Columbine exposes the Queen’s infidelity to the King. The Lover flees and Pierrot’s silence, when pressed by the monarch to reveal the truth about the Queen’s unfaithfulness, condemns him to execution.

The drama begins in what is described as a ‘moon-lit Watteau garden’. Aristocratic revels en plein air are underway, the entertainments including a puppet-drama and court masquerade. However, tales are enfolded within tales: the marionettes introduced to us in the opening Musettes, which are interweaved between Sarabande movements, are revealed to be puppet-players who simulate the actions of their puppet counterparts (the latter are placed on a ‘slightly raised knoll’ to the rear). Subsequently, the courtly audience slip in and out of disguises - cloaks, masks, costumes. Following the libretto as I listened to the recording, I tried to imagine the opera, with its on-stage and off-stage musicians and singers, ‘in the theatre’: presumably it is almost impossible to determine who is who, who is real/a player? We/the regal on-lookers are told by the puppet quartet that we are ‘in the play’? And, which is the ‘true’ Pierrot?

And, perhaps that’s the point … for, the duplicity and instability of identity lies at the dramatic core of Fête Galante. At the start, the puppet-players mime: “Since in deceit there is much pleasure,/ And since the world is all a cheat,/ Spare, O dancers, a moment’s leisure,/ Watch our pointed brief deceit.” The pleasure soon turns to pain. What musicologist Elizabeth Wood has described as a ‘psychological masquerade’, with a ‘troubling aura of sexual subterfuge which Smyth echoes’, exposes such ‘pleasure’ as morbid and dangerous. Wood - who has contributed greatly to our appreciation of Smyth’s work, life, and the relationship between the two - reminds us that Pierrot tells us, “Fooling’s a grim and dangerous trade”: ‘as it was, in life, for Ethel Smyth, Maurice Baring [… and] others whose ‘deviant’ and illicit sexual identities, roles, behaviors, and expressions society and culture condemned and punished’. [1]

The neoclassical flavour of the score - baroque dances and an unaccompanied madrigal alternate with solo and duo vocal passages which adopt an arioso, speech-melody idiom - is both reflective of some predilections of the period (Poulenc, Stravinsky, da Falla and others composed neoclassical opera ballets around this time) and apt for Smyth’s presentation of multiplicity and instability of identity.

Smyth offered two different orchestrations for small ensemble and here we hear flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, timpani/percussion and strings, with an onstage band (Dominic Saunders, piano; Miloš Milivojevic, concertina; Steve Smith, banjo). The seventeen-strong Lontano Ensemble strikes a vibrant note in the opening Sarabande movements, the individual voices clearly distinguished (we hear prancing clarinet and breezy flute against spiky celli pizzicatos, for example). The strings’ tone is quite grainy and the accents bright; rhythms are imposing but agile. There’s an edgy vibe: occasionally I caught an anachronistic scent of Peter Greenaway. With the entry of the vocal Musette, there is a shift to a more lyrical ambience - “Hushed is the world, faded the light,/ O magic hour, hour of delight,/ Heart against raptured heart beating.” - though there are interesting harmonic nuances and the alternation of the dances keeps the listener on their toes. I was surprised at the fullness of the vocal sound: even if the soloists have joined the chorus, there are apparently only fourteen voices, but the plushness achieved suggests many more.

As the King, Simon Wallfisch’s vibrato-inflected surges sound rather sinister, as he attempts to ‘claim’ Columbine for the second dance; Charmian Bedford’s response perfectly captures both the indignant pride and unnatural movements of the ‘puppet’. Rich inner instrumental voices slyly colour the Queen’s profession of support for Pierrot. When Columbine departs with Alessandro Fisher’s Harlequin, the viola seeming to belie the earnestness of Carolyn Dobbins’ professions: how could Columbine turn “From such a handsome, melancholy love/ For any other!”, the Queen sympathises - defying Wallfisch’s accusation, by turns passionate and portentous, “For me alone, there’s nothing!”, even as she turns to her Lover, “Sir, we are not alone …”.

Bedford brings integrity to Columbine’s suffering, in the face of Pierrot’s indifference and the urgent wooing of Fisher’s Harlequin as he seeks to whirl her from his rival’s arm. De la Martinez keeps the dances swirling forwards, capturing the slightly bitter spirit of ‘play’ and ‘divertissement’, even as drama darkens. The shadows truly fall when baritone Felix Kemp sings Pierrot’s central aria, an abstract meditation on love, introduced by sonorous double bass and pliant strings, the voice ushered in by Andrew Sparling’s seductively improvisatory clarinet. Kemp pays careful attention to both the text and the vocal phrasing, and the woodwind dialogues and viola solo add emotive weight.

Pierrot’s reflections are ironically interrupted by what seems to be a perky, unaccompanied madrigal, but the piquant harmonic juxtapositions and asymmetrical rhythms, no less than the metaphysical conceits of the text (once attributed to John Donne, but now thought to be by William Herbert), which are a perfect representation of the opera’s own doublings, undermine any semblance of ease: “Soul’s joy, now I am gone, and you alone, which cannot be,/ Since I must leave myself with thee and carry thee with me.”

During the garden tryst, tenor Mark Milhofer conveys the Lover’s relaxed romantic ardour which is darkened by a hint of suppressed power and anger. De la Martinez pushes the duet towards a climax of ardour: strings oscillate, a muscular bass line is etched by double bass pizzicato, the instrumental textures are richly layered. Janey Miller’s pointed oboe replaces the clarinet when Kemp’s Pierrot announces his presence and the Lover flees, but the sinuous clarinet returns when the King demands that Pierrot disclose his knowledge: gruff strings and forceful timpani alternate with reedy wind, and the stumbling rhythms undermine the King’s sonorous essay at imperiousness as Wallfisch works the text well.

Poignancy is added in the closing stages by Clare O’Connell’s beautiful cello utterances, which usher in Pierrot’s honest admissions: “Lovers pursue and maidens fly,/ Ghosts that chase a phantom bliss,/ Ask a wiser fool than I/ Where the truth is, where the lie/ In a stolen kiss!” But, such moments of respite and sincerity are brief: de la Martinez rightly strives onwards towards the painful intensity of the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance which rounds off the drama with frightening urgency: “Heigho! Ho!/ Hey nonny no!” the singers cry as the timpani howls and Pierrot dies: by his own hand - he is seen to stab himself with the knife intended for his rival Harlequin - or by the hangman’s noose? It is not clear. The closure of the Musette frame offers little consolation.

The companion work offered by Retrospect Opera is Liza Lehmann’s dramatic ‘recitation’, or melodrama, of 1908, The Happy Prince - a musical retelling, spoken by Dame Felicity Lott and accompanied by pianist Valerie Langfield - of Oscar Wilde’s tale. Also included are recordings from 1939 of Sir Adrian Boult conducting The Light Symphony Orchestra in extracts from Fête Galante, The Boatswain’s Mate and Entente Cordiale.

Fête Galante had an after-life: in 1924 Smyth arranged it as an orchestral suite (1924) and later, in 1932, she expanded the opera into a ballet for which Vanessa Bell painted the scenery. On 4th March 1934, The Observer reported that the ‘Queen attended a concert at Albert Hall yesterday afternoon, and for the first time heard Dame Ethel Smyth conduct her “March of the Women”.’ The first public performance of the March had also taken place at the Hall, in 1911, conducted by Smyth; the Observer journalist observed that an ex-suffragette remembered when Smyth (imprisoned for suffragette activities) conducted the March from her prison cell using toothbrush as a baton. The occasion of the 1934 concert was Smyth’s 75th birthday; the second half included Fête Galante, and at the close of the evening, the ‘Queen led the outburst of applause when Dame Ethel was presented with a gigantic wreath of flowers almost as big as herself. She was cheered back to the platform again and again.’

One can only add, “three cheers!” to Retrospect Opera and Odaline de la Martinez for allowing us to enjoy Smyth’s disturbing, dramatic ‘dance-dream’ once again.

Claire Seymour

[1] Elizabeth Wood, ‘The Lesbian in the Opera: Desire Unmasked in Smyth’s Fantasio and Fête Galante’ in eds. Blackmer and Smith, En Travesti: Women, Gender, Subversion, Opera (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), p.296.

December 26, 2019

A compelling new recording of Bruckner's early Requiem

On his death, Seiler bequeathed Bruckner his Bösendorfer grand piano, which Bruckner kept all his life, and upon which he composed all his subsequent compositions; it now stands in the Bruckner memorial room of the St Florian monastery.

On 22nd November 2018, the RIAS Kammerchor performed the Requiem and Bruckner’s Libera me in F minor in the Chamber Music Hall of the Berlin Philharmonie, with the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin and four vocal soloists: Johanna Winkel (soprano), Sophie Harmsen (mezzo-soprano), Michael Feyfar (tenor) and Ludwig Mittelhammer (baritone). Conducted by Łukasz Borowicz, and employing the new Anton Bruckner Urtext Complete Edition edited by Dr Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, this live performance has been captured - alongside other early, funereal, choral music by Bruckner - for this recently released recording on the Accentus label.

The Requiem was first heard on 15th September 1849, the anniversary of Seiler’s death, with Bruckner himself playing the organ. A scholarly article (in German, French and English) in the liner booklet by Dr Cohrs, who is Head of the Vienna Bruckner edition, informs the listener about the complex issues relating to the sources of the Requiem: while Bruckner gave the autograph score to Franz Bayer in 1892, the composer’s original parts went missing after his death, and absence led to some inaccurate assumptions about subsequent revisions made by the composer. Modest forces were employed at the first performances: eight singers, including the soloists, seven strings, three trombones and organ. This recording adopts the forces - 22 strings, horn, three trombones and organ, and a 35-strong chorus - that were available to Bruckner for the performances of his masses at the Hofburg Chapel at the Imperial Palace in Vienna, where from 1878 Bruckner was organist.

If the syncopation and low, dark register of the opening bars of the ‘Requiem aeternum’ summon (sometimes almost verbatim) echoes of Mozart’s Requiem to mind, then the prevailing idiom seems to me more consistently to pay homage to the Baroque, or at least to a pre-Beethoven/Schubert Viennese age, though this is not to suggest that the music is lacking in interest: there are some striking timbral glances as the three trombones assert their robust nasal presence, for example. From the opening bars it is clear that music’s melodiousness and straightforward harmonic dramas would undoubtedly provide much enjoyment for able amateur choirs, for whom this recorded performance - persuasive of tempo, vivid of vocal colour, ever alert in the continuo - would provide an exemplary model.

The ‘Dies irae’ similarly echoes Mozart in its rhythmic vigour, energised strings, thunderous bass accents and stirring choral cries, which alternate with the solo quartet. But, however derivative Bruckner’s idiom, the chorus here summon a terrifying forward sweep, and the urgency carries through to solo voices - tenor Michael Feyfar’s lyricism in the short passage of recitative provides welcome respite - and the movement between moods and groupings is smoothly and coherently negotiated. The choral counterpoint feels more than an academic exercise, not least because of the excitement contributed by the string playing and the flexibility of the voices.

Baritone Ludwig Mittelhammer doesn’t quite have the solidity at the bottom to match the organ and low strings in the ‘Domine Jesu’, but when the chorus enter tremendous forward momentum is generated. And, the ‘Hostias’ for male solo quartet with trombones - the latter really make their presence felt - is beautifully tuned and blended. The fugal ‘Quam olim Abrahae promisisti’ (which follows Mozart’s formal example) is notable for the way in which the bass line and organ embed such vigour-inspiring foundations for the polyphonic architecture above; similarly striking is the grandeur of the tutti cries, ‘Gloria!’, in the ‘Sanctus’, which are further vivified by throbbing instrumental triplet quavers.

The ‘Benedictus’ for solo quartet feels especially Mozartian. The Andante marking is interpreted with sensible freedom - this is no amble in the park, but a purposeful statement of faith - and features a solo for horn in Bb which, Cohrs explains, the parts show was in Bruckner’s day played on the horn by a bass trombonist. Winkel’s soprano sits dynamically atop the solo quartet, the line inflected with lovely emphasis and gestures, while Feyfar’s tenor responses are notably pliant. The brief a cappella choral conclusion is honest and true, and leads into a short, but intensely beautiful ‘Agnus Dei’, in which Sophie Harmsen’s solo mezzo melody is full of feeling. The ‘Cum Sanctis’ makes for assertive conclusion: all spiky strings and majestic voices.

In his seventies, Bruckner is reported to have passed judgement on his Requiem: ‘It isn’t bad!’ That probably sums it up, but this performance is both persuasive and affecting. The Requiem lasts just under 30 minutes, and the rest of the Accentus disc comprises smaller choral works by Bruckner.

These include imposing works such as the Libera in F minor (Cohrs D02) and ‘Brüder, trocknet Eure Zähren’ (Vor Arneths Grab , Cohrs G01) which were performed at the funeral rites for Bruckner’s patron Prelate Michael Arneth on 28th March 1854. The former has some striking harmonic nuances at the start, but lapses into rather perfunctory polyphony, though the sense of strong belief never wavers, and here it is followed by an Aequales in F minor - the form draws upon the eighteenth-century tradition of performing music for three trombones and other wind at occasions of mourning - arranged by Dr Cohrs, and standing in for a work that the scholar believes originally followed the latter - a substantial funeral chorus - but which is now lost. ‘Brüder, trocknet Eure Zähren’ may itself be unadventurous harmonically and formally, but it has the beautiful directness of a Bach chorale and is sung here with genuine commitment and drama, and it resolves with consoling softness.

Several of the works included are world premiere recordings, such as the Libera in F (Cohrs E01) which Bruckner composed in 1845 when he returned to St Florian to become teaching assistant and organist-in-waiting at the monastery. The truthfulness of the performance here is very touching. Similarly recorded for the first time is ‘Vereint bist, Tönehheld und Meister’ (Nachruf! / Trösterin Musik, Cohrs H05) for large male chorus and organ, a work composed in memory of Josef Seiberl - Bruckner’s friend and successor as organist at St Florian who died on 10 th June 1877 - arranged here by Cohrs for smaller mixed choir and organ, but retaining all of the drama and passion of the original. The homophony and unisons defy the listener to ignore their pleas, and the sonorous organ entry expands the canvas thrillingly.

Dr Cohrs offers clear explanation regarding the performance decisions that have been taken, and why - in the light of missing scores, and ambiguous or contradictory extant sources - and of the circumstances of composition and first performances. The performance was clearly an endeavour characterised equally by scholarly endeavour and musical belief: it follows the 2018 Accentus release of Bruckner’s early Missa Solemnis , with almost the same quartet of soloists, tenor Sebastian Kohlhepp being replaced here by Feyfar.

Borowicz and his singers and players respect the sincerity of this music. Perhaps this disc might appeal most to those who are already Bruckner aficionados, but anyone whose heart is touched by Bruckner’s motets will surely find the directness of both the music and delivery undeniably powerful. This is authentic and beautiful music-making.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bruckner%20Requiem%20Accentus.jpg image_description=Accentus ACC 30474 product=yes product_title=Anton Bruckner: Requiem product_by=RIAS Kammerchor Berlin, Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin, Łukasz Borowicz (conductor) product_id=Accentus ACC 30474 [CD] price=$16.99 product_url=https://amzn.to/2t8lqDyDecember 22, 2019

Prayer of the Heart: Gesualdo Six and the Brodsky Quartet

A sequence of Renaissance and modern works - the former frequently inspiring the latter, both directly and less consciously - was presented in an unbroken sequence which was performed and choreographed with serene composure, concentration and fluidity. Considerable thought, preparation and rehearsal had clearly been invested in both the concept and its manifestation. The seven singers (conductor Owain Park occasionally took a place amid his ensemble) began in the Hall gallery: their subsequent descent to the platform was effected inconspicuously and fluently; at times they departed leaving, the string quartet players alone on stage; the latter arranged themselves in a central arc, cellist Jacqueline Thomas seated, then later formed a line perpendicular to the rear wall. Finally, the singers and musicians came together in a broad semicircle which interlaced voice and strings, embracing and uniting all as one. If this sounds a little laboured, or contrived, that might have been a risk, but it was one that was avoided, so persuasive was the performers’ sincerity and cohesiveness.

The music of John Tavener framed the sequence. Into the darkness of Hall One pulsed the repetitive life-beat of Prayer of the Heart as, supported by the strings’ sustained pianissimo purity, the monastic mantra floated from on high. The work was originally composed for Björk and the Brodsky Quartet, to benefit the charity The Chain of Hope, and the Icelandic singer had been instructed to ‘sit on a low stool, bowing towards the heart’ to facilitate ‘the soul’s concentration, and its unification in ecstasy’. On this occasion the singers moved meditatively around the gallery, their sedate but fluent procession matching the work’s slow harmonic progression.

Subsequently, old and new were fused in a beautifully reflective chain. ‘Parce mihi Domine’, a setting of a text from Job by the sixteenth-century Spaniard, Cristóbal de Morales, as ‘reimagined’ by Latvian Ēriks Ešenvalds as a four-voice introduction to his 2005 oratorio Passion and Resurrection, initiated the musical and religious time-travel, the slow musical metamorphoses perfectly reflecting the wider concept of the evening. Arvo Pärt came to mind, not for the last time during the concert, and not least in the vigour, complementing the cleanness of sound, that was conjured by string interjections, harmonic interest and textual detail, such as the stirring crescendo through ‘et si mane me quaesieris’ (for now shall I sleep in dust).

This served as an entrée to Roxanna Panufnik’s Votive for string quartet - commissioned in memory of Cavatina Chamber Music Trust co-founder, Pamela Majaro - in which tentative gestures ushered in a yearning cello melody that became an elaborate vocalise, passed ever higher across the players, increasing in intensity and cadencing in a joyful major-key climax, the players’ flourished final up-bows conveying the work’s jubilant aspirations. Panufnik’s O Hearken followed. Setting verses from Psalm 5, it was a choral summons in which rich homophonic layerings formed a soundscape of gentle dissonance.

Owain Park’s Phos hilaron, a setting of one of the earliest Christian hymns, was sung in darkness, Gesualdo Six taking position in the Kings Place aisles and singing from memory, following countertenor Guy James’s well-defined and assertive solo melody. It was preceded by Hildegard von Bingen’s O Ecclesia, in which the tenor solo sat upon a warm hum and soft strings (no credit to an arranger was given); this was lovely singing but I felt as if the opportunity for more dramatic communication was not grasped.

There was drama, though, in Panufnik’s This paradise, a setting of Canto 23 from Dante’s Paradiso, the third part of the Divine Comedy, in which the combination of string quartet and six male voices produced some startling timbres and colours: portamento hums against tremulous gestures and fragile harmonics at the start of ‘A bird … her heart ablaze, awaits the sun’; rhythmic muscularity in ‘Triumphing the soldiery of Christ’; a storm of trills and scalic flights in ‘… bolts of fire, unlocked from thunder clouds’; echoes and piling seventh chords, adding enigma to the concluding ‘And so the perfect circling of that tune sealed its conclusion’.

Sarah Rimkus’s My Heart is Like a Singing Bird connected us to the madrigalian grace of the Elizabethan Renaissance by way of Britten’s Ceremony of Carols; Hennig Kraggerud’s Preghiera, written for the Brodsky Quartet, moved from meditation to improvisatory momentum, offering first violinist Gina McCormack some flights of fancy and martial energy into which to bite her musical teeth.

Then, we arrived at what seemed to the musical destination of this programme: Panufnik’s ‘completion’ of her father Sir Andrzej Panufnik’s setting of Polish poet Jerzy Pietrkiewicz’s two-stanza prayer, Modlitwa; and, O Tu Andrzej commissioned by the Brodsky Quartet in memory of her father. The former sounded, to my ear, full of Eastern European echoes - on this first hearing, I sensed the sound-world of Dvořák and Janáček rather than anything specifically ‘Polish’ - and featured strongly characterised solos by baritone Michael Craddock and tenor Joseph Wicks, which conversed with the cello’s harmonically inflected excursions. The latter saw Park join his ensemble once more to add his voice to the piling-up stacks of semitonal dissonances and harmonic piquancy.

We returned to Tavener at the close, his setting of The Lord’s Prayer bringing an expertly delivered sequence to a close, and in which it was lovely to see the experienced members of the Brodsky Quartet take their lead from Park and his young singers, and to feel all involved relish the collaboration.

So, after such pleasures, where’s the ‘but’? Well, if you were happy to sit back, shut your eyes and submit to the spiritual bliss, then all was well and good. If, on the other hand, you wanted to engage with the texts and reflect on the meaning conveyed as note and word conversed, combatted and entwined, there were problems: not least that, in the gloom in Hall One, it was impossible to read a single word of the printed texts provided in a supplementary programme sheet. But, also, Gesualdo Six threw the consonants into a sonic space where they became instantly undiscernible and irretrievable. This was a pity. An opportunity to really appreciate the spiritual union of words and music was lost.

But, given the numbers who rose to their feet to thanks the performers at the end of the concert, I guess this was of less irritation to most at Kings Place than it was to this listener, concerned as I was to experience the performance intellectually as well as emotionally. Never mind, next time I will simply shut my eyes and enjoy!

Claire Seymour

Prayer of the Heart : Brodsky Quartet & Gesualdo Six

John Tavener - Prayer of the Heart; Morales/Ešenvalds -Parce mihi Domine; Roxanna Panufnik -Votive, O Hearken; Hildegard von Bingen - O Ecclesia; Owain Park - Phos Hilaron; Panufnik -This Paradise; Sarah Rimkus -My heart is like a singing bird; Henning Kraggerud - Preghiera (Prayer); A & R Panufnik - Modlitwa, O Tu Andrzej; John Tavener - The Lord’s Prayer.

Kings Place, London; Friday 20th December 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gesualdo%20Six%20Ash%20Mills.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Prayer of the Heart: Gesualdo Six and the Brodsky Quartet at Kings Place product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Gesualdo SixPhoto credit: Ash Mills

December 20, 2019

The New Season at the New National Theatre, Tokyo

Rosi left Japan the following year, with a sense of disillusion: “The Japanese are rotten pupils. They can’t do it – they are not ready.” But he had actually demonstrated that the Japanese could do it, and were ready, and there has been a more-or-less continuous tradition of producing Western operas in Japan ever since, one interrupted only by World War II.

In the century since 1917, a few important dates stand out. In 1927, NHK, the Japan Broadcasting Corporation, began regular opera broadcasts (just a year after Italy), greatly enlarging the audience for what was still, for most Japanese, a very novel medium. In 1934, the Fujiwara Opera Company was formed in Tokyo, Japan’s first opera company to have more than a brief existence. They managed to weather the war period and operated independently until 1981, before being merged into the Japan Opera Foundation. In 1952, the Nikikai (literally “second-generation association”) company was created, later becoming the Nikikai Opera Foundation, and, in 2005, the Tokyo Nikikai Opera Foundation. Finally, the New National Theatre, Tokyo (NNTT) was opened in 1997 specifically for the presentation of Western performing arts (Japan’s other five national theatres are all devoted to indigenous forms of theatre). It includes what is described as “the first Opera House in Japan designed specifically to stage opera and ballet,” and this 1,800-seat theatre (one of three NNTT stages) has, since 2007, been named Opera Palace. It was inaugurated in October 1997 with a specially commissioned opera by Japan’s most famous opera composer, Takeru by Ikuma Dan (1924-2001).

Since Rosi’s Cavalleria, some clear patterns stand out. There has been an overwhelming preference for repertoire works in Italian, though these are interspersed with a good deal of Wagner, a smaller amount of Richard Strauss, and a few Japanese operas. Japanese opera singers need to be able to sing in Italian if they are to have viable careers. The canon has been conservative: it is unusual for any opera earlier than Mozart, or later than Puccini, to be performed; rare for lesser-known composers to be staged at all. Production styles have generally been conservative too – restrained and respectful, designed to foreground the work, not the director. The number of productions is surprisingly large, but the number of performances surprisingly small, suggesting that opera in Japan – a country of some 126 million people – has a small but loyal audience. And Tokyo has always been absolutely dominant. No other Japanese city has been able to establish itself as a significant base for opera, and regional productions tend to rely on bringing in a few star singers from Tokyo.

There is no doubt that the NNTT has established itself as the jewel in the crown of Japan’s current operatic scene, and it is also, thankfully, breaking down the sort of insularity that, until very recently, made it almost impossible for anyone not resident in Japan, and not conversant with Japanese, to actually find out what productions were taking place here, and to obtain tickets for those productions. The NNTT now advertises its productions in English and sells tickets online, on an English website. And in October 2018 the new and very pro-international artistic director Kazushi Ono took the truly historic step of supplying surtitles in both Japanese and English, a practice which has become standard in the present season. There is certainly no longer any reason for foreign visitors to Japan, currently numbering around 30 million a year, not to enjoy the very high-quality productions the NNTT offers, and it has been encouraging to see an increasing number of non-Japanese faces in the audience. The NNTT’s English website is here www.nntt.jac.go.jp/english

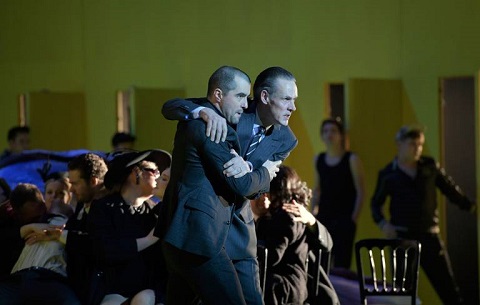

The current NNTT season began on 1 October with an unusual, very welcome excursion into Russian repertoire: Eugene Onegin directed by Dmitry Bertman. This was a new production made for the NNTT, but also a vintage one, for it was designed as a sort of homage to Konstantin Stanislavsky’s epochal 1922 production, enticingly reproducing some of the latter’s staging, centred on a very versatile, omnipresent, neo-classical portico structure. It was visually delightful and offered a striking, thought-provoking interpretative novelty by making Lensky clearly the author of his own fate: he ran forward into his opponent’s line of fire when Onegin was showing his contempt for the duel – and his humanity, too – by harmlessly discharging his pistol into the trees. There was a strong international cast with Vasily Ladyuk as Onegin, Evgenia Muraveva as Tatyana, Pavel Kolgatin as Lensky, and Alexey Tikhomirov as Prince Gremin; the rest of the cast and chorus was made up of Japanese singers. The conductor was Andriy Yurkevych, making his first appearance at the NNTT, and he led the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra in a ravishing reading of the score. This was unquestionably the finest production of Onegin I’ve seen anywhere and a huge credit to all involved.

The season continued on 9 November with Donizetti’s Don Pasquale in the Stefano Vizioli production first staged at La Scala in 1994, and subsequently widely performed in Italy. This was the first time the NNTT had staged Donizetti’s comic masterpiece. Given that most Japanese would not have seen the opera before, the program contained some rather surprising statements. “Of all the opera buffa in the standard repertory, Don Pasquale is quite possibly the hardest to love,” began Mark Pullinger’s introductory essay. “It is only in appearance that Don Pasquale is a jolly opera,” began Vizioli’s director’s notes. One feared the worst, but in fact Vizioli’s is an exuberant and refreshingly “straight” take on the opera, and in his hands it was both easy to love and jolly, though the Japanese audience didn’t seem as entertained as I expected. Clearly an opera concerning an old man developing silly fantasies about a young girl who doesn’t really exist, then getting roundly punished for them, can have a serious resonance in an age of internet dating scams and the #MeToo movement. It may be, too, that Japan’s own culture of silly, but disturbing, fantasising about supposedly “innocent” young schoolgirls (see for example: “Society helps sustain Japan's sordid sexual trade in schoolgirls” ) also conditioned the audience response. Roberto Scandiuzzi made a very fine Don Pasquale; Norina was sung by the young Armenian soprano Hasmik Torosyan; Dr. Malatesta by Biagio Pizzuti; and Ernesto by Maxim Mironov. All these principals sang and acted stylishly, conveying a delectable sense of intense self-interest, and there was an intriguing suggestion that the relationship between Norina and Malatesta was far from innocent. The smaller roles were taken by Japanese singers, and the choral scene in Act III became an extraordinarily lavish affair set in Don Pasquale’s kitchen. Corrado Rovaris conducted the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra with sparkling panache.

The third production of the new season, first staged on 28 November, was La Traviata – a third outing for Vincent Boussard’s production, originally designed for the NNTT in 2015. After the wonderful sets for Eugene Onegin and Don Pasquale, this seemed rather impoverished visually, relying heavily on some rather strange projections. For reasons I have been unable to fathom, Violetta’s party in the first act, and Flora’s in the second, were both set in the foyer of the Opéra Garnier, Paris, opened in 1875, a generation after the death of Marie Duplessis, the historical model for Violetta. But oh dear, the foyer of the Opéra Garnier in a rather ghostly projection AND a huge suspended chandelier! Surely, surely Boussard wasn’t trying to evoke The Phantom of the Opera, and yet it was hard to keep that annoyingly distracting thought out of one’s head. Musically, the production was a splendid advertisement for Japanese singing, for the unquestionable standout performance was local star Shingo Sudo as Giorgio Germont. His beautifully mellow, sonorous voice conveys a remarkable sense of conviction, and I think one result was that Germont’s viewpoint came to dominate the opera. This was the more the case in that Dominick Chenes made a rather ordinary, forgettable Alfredo, and in the performance I saw (1 December), Myrtò Papatanasiu as Violetta only really impressed in the third act, which was very affecting. Before that, her voice had sounded rather forced and screechy whenever volume was required. Ivan Repušić made his first appearance at the NNTT, conducting the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra with great authority.

The NNTT will start 2020 in a conservative fashion, with revivals of Jun Aguni’s production of La Bohème in January, of Josef Ernst Köpplinger’s Il Barbiere di Siviglia in February, and Damiano Michieletto’s Così fan tutte in March. But then in April comes Laurent Pelly’s production of Giulio Cesare, remarkably the NNTT’s first staging of a baroque opera on the main stage, and in June we can look forward to one of the most ambitious projects the NNTT has ever undertaken, a new production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg directed by Jens-Daniel Herzog in a joint international production with The Salzburg Easter Festival, Semperoper, and Tokyo Bunka Kaikan: this is designed to tie-in with Japan’s hosting of the 2020 Olympics. It is a good time to be an opera lover in Japan, and in time I hope the NNTT will start using its lavish financial and artistic resources to mount the great, but neglected, operas not being given anywhere else.

David Chandler

image=http://www.operatoday.com/2019Eugene%20Onegin_3123_D9C06889.png image_description=Scene from Eugene Onegin [All photos courtesy of New National Theatre, Tokyo] product=yes product_title=The New Season at the New National Theatre, Tokyo product_by=A review by David Chandler product_id=Above: Scene from Eugene OneginAll photos courtesy of New National Theatre, Tokyo

December 19, 2019

Handel's Messiah at the Royal Albert Hall

Perhaps somewhat in the spirit of enquiry, we went along to this year's performance of Handel's Messiah at the Royal Albert Hall on Wednesday 18th December 2019. Christoph Altstaedt conducted the Philharmonia Chorus and Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, with soloists Natalya Romaniw, Marta Fontanals Simmons (replacing an ailing Katie Bray), Egan Llŷr Thomas and William Thomas.

The chorus numbered some 130, and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra fielded only a moderate size team, with just two oboes and one bassoon, with continuo provided by a portative organ and harpsichord. The fine team of young soloists are perhaps best known for their operatic roles: Natalya Romaniw recently made her debut as Puccini's Tosca with Scottish Opera and will be appearing as Puccini's Madama Butterfly with English National Opera in 2020; Marta Fontanals Simmons sang the lead role of Hel in Gavin Higgins new opera, The Monstrous Child at the Royal Opera House; Egan Llŷr Thomas is currently a Harewood Artist at English National Opera; and despite still being on the opera course at Guildhall School of Music and Drama, William Thomas has already made his debut with Vienna State Opera.

Conductor Christoph Altstaedt took a modern, period-performance inspired view of the work. The days seem long gone when modern orchestras could completely ignore the historically informed approach, and nowadays performing Baroque music requires the delicate navigation through a tricky field. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra played with admirable crispness and lightness, and I very much enjoyed their performance throughout the evening. Their two solo spots, the overture and the Pifa, were finely done with plenty to enjoy. Altstaedt's tempos were on the fast side, and he certainly took no prisoners, yet his performers, both soloists and choir, we well up to the task and throughout the evening we had some admirably fleet passage work.

In the early 1980s, I worked with a veteran choral conductor in Edinburgh who commented that the overall timing of Messiah could be gauged from the speed at which the choir could sing the semi-quaver passages. In the case of the wonderfully admirable Philharmonia Chorus that seemed to be at whatever speed Altstaedt wanted, and they sang with a nice lightness and unanimity too.

What let the performance down, for me, was the issue of balance, which is an area where many modern instrument performances go wrong. In the late 18th century when the large-scale Handel oratorio performances were born, it was common to multiply up, so that with a large body of strings you had a larger group of wind. Here we had just two oboes and a bassoon, and whilst I know that the wind parts are not essential, it seems redundant to have instruments playing that are inaudible in many of the large scale choral passages, we seriously needed to double or triple the wind numbers to provide balance.

The other area of balance was with the portative organ: it was adequate for continuo when just the orchestra was playing but simply did not have enough power to support a choir of 130 singers. The result was that, in many of the large scale choruses, the sound was basically that of singers and strings, with no extra colour from wind or organ. It seemed a shame that the Royal Albert Hall organ, playing the scaled-down registrations, could not have been used.

We heard a pretty standard version of Messiah, with no surprises but a few cuts. Part One was given complete, there were cuts at the end of Part Two and significant reductions in Part Three.

Nowadays, singing Puccini's heroines on the operatic stage and singing the soprano solos in Handel's Messiah is not that common, but in the earlier part of the 20th century singers would not have found the idea unusual. Natalya Romaniw sang with a lovely flexibility of line and attractive bright tone, and if the top of her range lacked something of the ease that a lighter soprano might have brought to the role, she more than compensated by her intelligent shaping of Handel's vocal lines. She brought a nice sense of drama to the Part One sequence and made 'Rejoice greatly' really sound as if she meant it! 'How beautiful are the feet' in Part Two was nicely shapely whilst 'I know that my Redeemer liveth', sung to quite a flowing tempo, was full of the confidence of belief.

Marta Fontanals Simmons, a last-minute replacement for Katie Bray who is ill, sang with lovely straight, well-modulated tone. Her Part One solos were full of lovely sculpted phrases and 'Refiner's Fire' had some impressive passage-work. In Part Two, 'He was despised', which was sung complete with its da capo, and had quite a fast tempo, but Fontanals Simmons gave it a sober performance, singing with lithe tone yet full of meaning.

Tenor Egan Llŷr Thomas started somewhat uneasily; in his trenchant performance of 'Every Valley' he seemed inclined to push the tone a little, perhaps worried about projection in the Royal Albert Hall, so we missed the sense of easy lyricism. But in the long tenor sequence in Part Two, he focused on the sheer drama of the music and impressed with expressiveness, approaching operatic vividness at some points.

Bass William Thomas impressed with his firm, dark tone and strong, flexible line in his solos in Part One, as well as some impressively fluid passage-work. 'Why do the nations?' in Part|Two was similarly exciting, taken at quite a fast tempo. And 'The trumpet shall sound' thrillingly combined resonant tone with a nicely fluid sense of line.

Conductor Christoph Altstaedt clearly relished having a large chorus which could give him both fluidity and speed (with impressively light and fast passage-work), but also weight and drama, not to mention the sound of 130 hushed voices. All this ensuring that the all-important choral contribution to the evening was both technically well crafted and highly satisfying.

Diction all round was excellent. Whilst I admit that I do know the words, it was gratifying to find how many of them both soloists and choir managed to get over.

Overall, this was a remarkably satisfying performance, demonstrating that large-scale accounts of Messiah work well in the right hands.

Robert Hugill

George Frideric Handel: Messiah

Natalya Romaniw (soprano), Marta Fontanals Simmons (mezzo-soprano), Egan Llŷr Thomas (tenor), William Thomas (bass), Philharmonia Chorus, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Christoph Altstaedt (conductor).

Royal Albert Hall, London; 17th December 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Natalya%20Romaniw%20Opera%20Omnia.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Handel’s Messiah, at the Royal Albert Hall product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Natalya RomaniwPhoto credit: Opera Omnia

What to Make of Tosca at La Scala

La Scala had assembled a starry team familiar to Milanese audiences: Anna Netrebko, Francesco Meli and Luca Salsi sang, Music Director Riccardo Chailly conducted, and Davide Livermore designed a new production. Each sought to do something new with Tosca, yet enjoyed uneven success.

Soprano Anna Netrebko, the only non-Italian involved, assumed the title role for the first time in New York last year, as part of her mid-career move into more dramatic roles. She still has plenty of vocal charisma. Her voice, once a lyric instrument, now has reserves of power and an enveloping dark resonance, especially down low. Yet this comes at the price of widening vibrato, occasional lapses of pitch, questionable diction, and a tendency to slide awkwardly into notes (including the first one of “Vissi d’arte”).

These vocal limitations render Netrebko’s characterization of Tosca rather generic. Puccini’s pious prima donna is a complex creature: in a second, she can shift from coy to sincere, irreverent to penitent, jealous to trusting, confident to frightened, and affectionate to enraged. Since Maria Callas revolutionized this role seventy years ago, most great singers have employed quicksilver shifts in vocal color, diction and tempo to convey these internal tensions. Not Netrebko, however, who alternates between more and less intense variants of the same lush and slightly stressed sound. Pushing out firm low notes in chest voice served her very well in portraying the anguish of Act II, but no other musical-dramatic affect came through as vividly. Some critics praise this approach as restrained and musical, but it is not for me.

Baritone Luca Salsi possesses the dark tone and vocal edge of a natural Scarpia. He is an intelligent singer who seeks to enunciate every phrase with precision and meaning. At times, particularly in Act II, when it mattered most and the acoustics of the set favored him, he seemed to inhabit the character totally. Yet, ultimately, he does not entirely command the vocal extremes of fearsome power, effortless elegance and serpentine menace required for this role.

On the night I attended, tenor Francesco Meli was indisposed. His understudy, the young Georgian Otar Jorjikia, has won prizes and launched a successful career over the past few years – not least as a favorite of Valery Gergiev at the Marinskii Theater. He went for it, using all his vocal capacity – and sometimes a bit more – to deliver everything one expects of an understudy: a solid and correct performance, very impressive high notes and a few quite moving moments. At the curtain, his gratitude to the prompter was charmingly clear. This may be a singer to watch.

Of the remaining singers, baritone Alfonso Antoniozzi, who also works as a stage director, was particularly impressive as the Sacristan. This was not the buffo priest one normally sees, but a regular guy afraid for his life. His full tone and exceptionally clear diction were a model of how to make an impression in a small role by getting the fundamentals right.

More radical were Chailly’s innovations as conductor. He restored a few dozen measures of music that Puccini cut after the first performance in 1900. Most noticeable were a short exchange between Scarpia and Tosca after “Vissi d’arte” and a meandering orchestral finale to the opera. These passages were interesting to hear, but Puccini’s judgement was right: Tosca is tighter without them. More problematic were the slow tempos and a thick sound Chailly drew out of the orchestra. To be sure, the playing, especially in the woodwinds, was excellent. Yet the generally symphonic approach lacked the lively snap of traditional Italian operatic style and threatened drag the performance down.

In staging Tosca, Livermore faced an even trickier task. Puccini’s operas, more than those of any other composer, resist radical production concepts. Early in the tenure of General Director Peter Gelb, the MET scrapped Franco Zeffirelli’s beloved 25-year old production of Tosca, with its loving reconstructions of Roman tourist sites, in favor of a grim and deliberately ugly take by Luc Bondy. The response was so hostile that Gelb apologized and soon commissioned David McVicar to design a yet another production that resembled Zeffirelli’s original. La Scala co-produced the Bondy Tosca, where the Milanese greeted it with similar revulsion.

So, Livermore surely had no choice but a return to realism – and he doubled down, going hyper-realistic. To that end, he deployed rolling scenery, a moving stage, flickering video screens, surreal projections, meandering extras, and on-stage fire in an effort to mimic the sweeping pans, computer graphics, constant motion, and stark lighting of popular Hollywood blockbusters. To top it all off, he chose to end each act with a visual tour-de-force in the form of a tableau mimicking a grand mannerist painting. So, in Act II, Tosca looks back on a body-double portrayed as a classical assassin, while in Act III, she becomes an ascending Virgin Mary suspended 10 meters above the stage. We are meant to see the characters, I assume, as they see themselves.

All this enhanced reality sounds compelling in theory but fizzled in practice. In a hyperactive Act I, the columns, statues and walls of the church moved dozens of times, the stage turntable twirled every five minutes, video screens turned on and off, and the entire stage slid up and down more than once. This chaos seemed only modestly annoying in the video broadcast but was fatally distracting – even laughable – in the theater. At the end of Act II, the technology failed: sets clanked and squeaked as a body double tried to sneak on stage, spoiling a quiet orchestral passage Chailly had carefully restored. Act III began badly, with the large angelic statue atop Castello Sant’Angelo flapping its (projected) wings, and reached rock bottom with the shimmering assumption of Saint Tosca.

Yet, amidst the visual chaos, one spine-tingling scene illustrates what might have been, had Livermore’s enthusiasm been balanced by thoughtful restraint. At the climax of Scarpia’s effort to break Tosca’s will by torturing of her lover in an adjoining room, he opens a door so that she is forced to watch. He orders his henchman to bear down (“Più forte! Più forte!”) as the orchestra begins an increasingly hysterical crescendo on a two-octave upward scale. At that moment, the entire stage began to rise slowly, reaching nearly the top of the proscenium and revealing a stark torture chamber beneath the elegant Palazzo Farnese.

Perfectly synched with the score, the overall effect was horrifying. I am sure Puccini would have loved it.

Andrew Moravcsik

image=http://www.operatoday.com/K65A1743%20%28002%29.png image_description=Anna Netrebko and Otar Jorjikia [Photo by Brescia/Amisano – Teatro alla Scala] product=yes product_title=What to Make of Tosca at La Scala product_by=A review by Andrew Moravcsik product_id=Above: Anna Netrebko and Otar JorjikiaAll photos by Brescia/Amisano – Teatro alla Scala

La traviata at Covent Garden: Bassenz’s triumphant Violetta in Eyre’s timeless production

Some sopranos in my experience have simply looked as if they are truly stricken by the tuberculosis which will ultimately claim Violetta’s life; but when the mesh curtain rises at the beginning of Act I in this revival, Bassenz is of such striking beauty you might believe she is untouchable to such illness. Her unblemished looks, her simple purity, perhaps stretches the limits of our belief in her frailty – although another way of looking at this particular Violetta is that her willingness to ignore her fate is a determined strength. It’s Bassenz’s completely nuanced performance, the way in which she so beautifully portrays a Violetta who is on a trajectory of decline, from her last throw of the dice to her spiritual transcendence in Act III, which unquestionably suggests this is a singer who is going to let her Violetta, as Dylan Thomas wrote, 'Rage, rage against the dying of the light' (though, of course, she never quite manages that).

La traviata is an opera which is set entirely inside – and, intrinsically, Verdi’s major character’s in the opera are rather internalised because of this. Any outdoor action is principally off stage and is rarely a deviation from the libretto in this production – Alfredo’s voice is simply heard, singing of love, as he walks down the street at the end of Act I, for example. Eyre does insert a series of shadows walking outside the perimeters of Violetta’s bedroom during Act III, though these perhaps allude to her impending death, with their grim reaper like malevolence, rather than any breeziness of people simply walking by.

The lengthy duet in Act II between Violetta and Giorgio Germont is in many ways the dramatic focal point of the opera (‘Pura siccome un angelo, Iddio mi diè una figlia’ and ‘Dite alla giovine, sì bella e pura’) – though dramatic doesn’t, or shouldn’t, imply indulgent. This scene can hang fire in many performances and rather did so here. This had less to do with Bassenz’s Violetta and Simon Keenlyside’s superlative Germont and rather more to do with the conductor, Daniel Oren, who lavished details over the score when they weren’t needed and broadened the tempo – which although never challenging his singers – rather tested my patience. With lesser singers, this act would have fallen apart but Keenlyside, in particular, has both magnetic stage presence and a magisterial voice to match.

Photo credit: ROH/Catherine Ashmore.If there is often a disconnect between opera productions and their librettos, Eyre and his set designer, Bob Crowley, have achieved uncommon lucidity and transparency. There is even an intelligence to this production if the singers are minded to perform in a particular way – which was the case here. Act II, Scene 1 – set in Violetta’s country house outside Paris – very much suggests a life being wound down. Paintings have been removed from the walls and are stacked against the corner of the room; there is a bareness here, a vast table where only one end of it has any apparent use. This is a setting where the focus of existence is entirely concentrated on one side of the stage. The contrast between Scene 2, the party at Flora’s house, couldn’t be more stark. Here Crowley has given us one of the most opulent sets imaginable – a brick-red Romanesque Coliseum which arcs around centre of the stage, beneath the most lavish golden baroque ceiling. The beginning we see in Scene 1 of Violetta’s descent into heartbreak is palpably deafening to the glittering brilliance of Scene 2. This is a vortex of decadence, of table-top dancing and gambling, of matadors and confused sexual identities, and Violetta is all but consumed by it like burnt leaves floating up from the embers of a wild-fire.

Consumed though one might have felt this Violetta had been at the end of Act II, it was the crushing debilitation of her weakness in Act III which appeared most surprising from this soprano. Her vulnerability, and the slow momentum way she approached her final collapse into Alfredo’s arms, just seemed symptomatic of a singer who rather lived this role. Bassenz’s voice could not particularly be called be subtle – this is a large, bel canto kind of instrument, a complete contrast to the Violetta of Ermonela Jaho who sang the role at the beginning of the year. Bassenz is not a fragile singer; this was not a Violetta which was cautious. Those Lohengrin-like opening bars of the Prelude do not reflect a singer who matches that gentle quality in the strings. Rather, this is a true coloratura sound of arresting power. At times, that dominance can be a little too arresting – during the Brindisi she tended to project centre stage, and in her duet with Alfredo (‘Un dì, felice, eterea’) her recovery seemed so absolute you rather wondered how miraculous her triumph over tuberculosis was becoming. But a magnificent ‘Sempre libera’ rather banished thoughts of caring one way or the other.

Bassenz is such a class act it was her Alfredo, Liparit Avetisyan, who rather suffered beside her, however. I think their chemistry was superb, and if the kisses were real, they were prolonged enough to suggest a genuine warmth and believability between these two singers. Avetisyan sometimes sounded stretched to the limits, and there were times where he simply broke the line. But there is a youthfulness to this tenor which doesn’t stretch the imagination – his ‘De’ mei bollenti spiriti’ had all of the urgency of ardour and ebullience it is supposed to convey.