January 31, 2020

Seductively morbid – The Fall of the House of Usher in The Hague

Patrons trickling into the theatre for Opera Melancholia heard anonymous quotes such as this one, to live chamber music by Philip Glass and Glass-inspired compositions by Daniël Hamburger. The words with which young adults tried to capture melancholy were poignant, but it was the somber pieces, especially the mournful cello and hollow percussion of Tissue No.1, that filled the house with gloom and set the scene for the main program.

Opera Melancholia is the latest production by OPERA2DAY, a small company based in The Hague that repeatedly gives its big sister in the capital a run for its money. It’s a thoughtfully constructed, progressively unsettling exploration of the nature of depression built around Glass’s opera the Fall of the House of Usher. According to the company, the work has never been staged in the Netherlands until now. Glass’s mesmerising opera is a fairly faithful adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s grisly tale, which lends itself to countless interpretations. While visiting his dejected friend Roderick Usher, Poe’s nameless narrator helps him entomb his twin sister Madeline in the family vault when she succumbs to a mysterious illness. Not having really died, however, she leaves her coffin and, falling upon her brother, kills him with fright. Thus the Usher family line is extinguished, as is their stately home. The narrator just manages to cross the causeway before the house comes crashing down into the tarn that surrounds it.

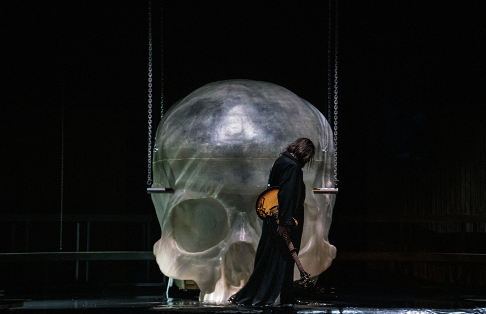

In director Serge van Veggel’s hands the opera becomes a psychiatric case study, complete with an introductory lecture by an engaging shrink and audience participation. The rotting house in the middle of the fetid lake is Roderick’s sick psyche, represented by a giant skull surrounded by an inky pond. It stands in the middle of an anatomical theatre, the kind in which cadavers were dissected for the benefit of medical students, a sober set that comes alive under Uri Rapaport’s kaleidoscopic lighting. Applying principles of psychoanalysis and Eastern philosophy, Van Veggel maps the three characters to parts of Roderick’s fractured self. He himself stands for his thinking self, or the Freudian ego, that has become disconnected from his feeling self (the Freudian id), embodied by his sister Madeline. The friend, named William in the opera, stands for consciousness or the socially acceptable superego. He’s the catalyst that forces Roderick to embrace his emotions, rather than burying them away, and heal his childhood trauma. This approach to psychotherapy probably wouldn’t bear close scientific scrutiny, but artistically it is an elegant thesis. And surely Poe, who knew a thing or two about the murky depths of the human psyche, would have approved.

If it all sounds a bit complicated, actor René M. Broeders, as the genial doctor dissecting Roderick’s mind, made it all seem plausible in his semi-improvised lecture. Be aware, if you go to a show, that his staff could question you about sadness while you’re having your pre-performance drink in the foyer, and Broeders could ask you to elaborate on your answers during his presentation. When was the last time you cried? And which piece of music best expresses melancholy? (The selections are added to a Spotify playlist. ) Responding to Broeders’ unforced humour and sensitivity, patrons were articulate and forthcoming with information, some of it rather intimate. The hall gasped when a GP reported that half of his patients presented with psychological problems, either explicit or masked by somatic symptoms. After this touching and entertaining briefing, the cast took over the stage to perform the opera/case study, and they were fantastic.

Tenor Georgi Sztojanov left a strong impression as the Usher family physician, a part which subsumed the role of the servant, originally written for a bass. William’s compassion came across in Drew Santini’s fine baritone. Brimming with optimism in the beginning, Santini grew visibly hunched as Roderick’s moroseness wore him down. In a casting master stroke, soprano Lucie Chartin seductively spun Madeline’s vocalises offstage while willowy Ellen Landa danced her onstage. Twitchy, obsessively repetitious choreography by Ed Wubbe of Scapino Ballet captured the seductiveness of the mad and the morbid. Snaking across the dirty water, her wet robe dragging behind her, Landa was a horrific and fascinating apparition. So was tenor Santiago Burgi as the unhinged Roderick, surrounded by books and bin liners stuffed with empty booze bottles, frenziedly banging out poetry on a typewriter. Van Veggel’s pitch-perfect direction certainly helped his phenomenally intense performance, but the fearless singing and artifice-free acting were all his own. Starting out slightly whiny to convey Roderick’s desperate neediness, his voice grew stronger and rounder as the “therapy” started to work. “If our souls could twine” to the dead Madeline was beautifully elegiac and when he recited Poe’s poem The Conqueror Worm (Van Veggel’s addition to the libretto) he kicked up a windstorm of manic energy.

As a successful case study, the opera doesn’t end in the destruction of the house of Usher, but in Roderick’s cure, but visually it’s still a dramatic finale that matches the musical climax, effectively constructed by conductor Carlo Boccardo. The New European Ensemble played for him with pulsating urgency. More assertive entrances whenever Glass introduces a new pattern would have propelled the musical narrative further, and at one point the orchestra overshadowed the trio of soloists, but the performance as a whole hummed with vitality. Opera Melancholica is on tour in the Netherlands, with alternating cast members, until the 19th of March. The lecture is in Dutch, but an outline in English is available. The opera is subtitled in Dutch and English.

Jenny Camilleri

Philip Glass: The Fall of the House of Usher

René M. Broeders, Physician-Director; Santiago Burgi, Roderick; Drew Santini, William; Georgi Sztojanov, Physician (Roderick on 19/2 and 11/3); Peter Rolfe Dauz, Physician (19/2, 28/2, 6/3 and 11/3); Lucie Chartin, Madeline; Emma Fekete, Madeline (3/3, 4/3, 6/3, 16/3, 18/3 and 19/3); Ellen Landa, Dancer; Dora Stepušin, Dancer (19/2 and 11/3). Gijs van Mierlo and four other actors take turns as the Child. Herbert Janse, Set Designer; Mirjam Pater, Costume Designer; Uri Rapaport, Lighting Designer; Ed Wubbe, Choreographer; Daniël Hamburger, Composer. Serge van Veggel, Director. Carlo Boccardo, Conductor. New European Ensemble. Seen at the Koninklijke Schouwburg, The Hague, on Wednesday, the 29th of January, 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Opera%20Melancholica047.png image_description=Scene from The Fall of the House of Usher [Photo by Marco Borggreve] product=yes product_title=Seductively morbid – The Fall of the House of Usher in The Hague product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri product_id=All photos by Marco BorggreveDaring Pairing Doubles the Fun by Pacific Opera Project

Those who might not have linked the plot circumstances of L’enfant et les sortileges (The Child and the Spells) to the garrulous Donato family in the Puccini, were helped along by the creative direction of the relentlessly imaginative Josh Shaw.

You see, Mr. Shaw has decided that the bratty boy in the Ravel, who is confined to his room as punishment for not finishing his homework, is the same young lad Gherardino who had the mission of bringing the character Gianni Schicchi to do the bidding of the scheming relatives of dead Buoso Donato, who has left all of them out of his will. The thinking is that the boy was so traumatized by these machinations, that he then has nightmarish Ravelian hallucinations as his toys, furniture, animals, and various and sundry inanimate objects come to life to torment him. To reinforce the connection, all of the performers from the Puccini are back (among new ones) and subtly recognizable as part of Gherardino/The Boy’s milieu.

This might have been just a cerebral exercise were it not for Shaw’s strong hand at defining character relationships, and skill at crafting richly detailed stage business. The plotters in Schicchi can often seem “greedy generic” but here each was a unique personality, informed by subtext. The controlled restlessness of the first half of the Puccini, settled into a nice stage picture when the notary documents the new will. This was matched in the Ravel by well-choreographed sequences that paraphrased the bustle in the first piece, even down to cascades of papers hurled through the air.

Scene from Gianni Schicchi

Scene from Gianni Schicchi

Josh Shaw, the designer also showed his customary ingenuity and flair. The rather ordinary 1950’s (death)bed room was a handsome enough box set, but it was in L’enfant that we delighted in the many here-to-fore hidden bells and whistles, with performers bustling through hidden passageways, popping up over the top of the walls, bursting out of an armoire, and even standing on top of it. The colorful and astonishing appearance of Fire as she jumps through the wall of the fireplace, with long fabric flames billowing behind her was alone the price of admission.

The variety and excellence of Maggie Green’s over the top costumes were certainly a major factor in the project’s resounding success. From the slightly rude placement of the Teapot’s spout, to the imposing tree, to all manner of witty treatment of small animals in the fantastical second opera, to the spot-on 50’s Goombah getups of the day’s opener, this was a magnificent visual achievement. Owing to the sheer numbers of attire, it is worth noting the contributions of Assistant Costume Designers Vanessa Karamanian and Gabriela Villa Lobos.

Marie Scott Mawji’s lighting design was simple but effective. There was especially nice pointing up of key exchanges, and the passage of time in both selections was well indicated with subtle adjustments of mood, and all this from a rather limited lighting inventory.

The cast could hardly be bettered. As Schicchi the charismatic baritone E. Scott Levin is a company favorite and for good reason. Mr. Levin never fails to engage us with his well-considered impersonations that are grounded in truth. Seldom has his sturdy baritone been heard to better advantage, and his dying geezer vocal mannerisms were delectably delivered. I especially liked his undercutting delivery of the climactic, deceptive “Gianni Schicchi’s” (in which he bequeaths valuable items to himself) in his own robust, penetrating voice. This was a masterful role assumption. Turning on a dime (or lira), he makes for a wily, characterful Black Cat in part two.

Scene from L’enfant et les sortileges

Scene from L’enfant et les sortileges

Tiffany Ho was such a winning Lauretta that we missed her when she was offstage for that extended plot stretch, especially since she totally beguiled us with such a poised, freshly nuanced O mio babbino caro. Her assured, silvery soprano also impressed as Ravel’s Princess and Owl. Jonathan Matthews proved an accomplished Rinuccio, his shining, appealing tenor making the most of his featured scenes. I only wish Mr. Matthews could invest the very top of his range with the same alluring brightness of the voice below the passaggio . Small matter when he and Ms. Ho blended so splendidly in their thrilling, full-throated duet passages. More than a pretty face, Jonathan’s antics as a daffy bouncing Frog in L’enfant showed off his theatrical range.

With little to sing in the Puccini, Kimberly Sogioka’s Gherardino seemed like an appropriately lumpy, bored teenager, but that all changed when she unleashed her ample, creamy mezzo in part two. As the enfant of the title she reacted appropriately to all the dizzying spells visited upon her, all the while singing with aplomb and stylistic accuracy. Her touching final word was the perfect punctuation to the day’s riches.

Sharmay Mussachio was a powerhouse as Zita, her beautifully colored contralto slicing through proceedings with incisive appeal and stature. As the White Cat in the French opus, Ms. Mussachio trades in her deviousness for a slinking, warmly vocalized feline that would bewitch even an avowed dog lover. Joel Balzun regaled us with one of the best star turns of the day as Ravel’s Clock. Wedding uninhibited, goofy stage business to his ringing, imposing baritone, Mr. Balzun served notice that at this moment, the stage was his. Earlier, he contributed a firmly presented take on Puccini’s Betto.

Tom Sitzler took complete ownership of Schicchi’s Simone, his well-modulated and personable baritone imparting much pleasure. His generous, pliable delivery also made the most of his brief scene as he tortured L’enfant as a particularly solid-voiced Arm Chair.Sonja Krenek deployed her attractive, soulful soprano to create a well-rounded Nella that captured our ear no matter how much turmoil ensued in povero Buoso’s bed chamber, and her scolding Mother in the Ravel was infused with unspoken love.

Scene from L’enfant et les sortileges

Scene from L’enfant et les sortileges

Danielle Marcelle Bond invests her every character with such commitment and decisive choices that it is hard to single out just one. Her vibrant, well-focused mezzo memorably dispatches her assignments whether as the plotting, earthy Ciesca in part one, or as part two’s pattering Tea Cup or gliding Dragon Fly. As Ms. Bond’s husband Gherardo in Schicchi, Robert Norman commendably matched her in wiliness and vocal achievement, but he arguably has his “moment” as a manic, moody, slightly libidinous Tea Pot which found his shining lyric tenor ringing out with joyous abandon.

Jared Daniel Jones’ well-schooled bass-baritone impressed mightily in his appropriately stolid delivery as the pontificating Tree in the Ravel. How did he stand so long, so still, on top of that cabinet? And how did he get up there? Earlier in the day, Mr. Jones also dispatched Puccini’s Marco with ease. Also in Schicchi, bass-baritone Peter Barber sang the relatively few but important lines of the notary Armantio with such luxurious tone and potent presence, that we sat up in our seats with “Who is THAT?” attentiveness.

As Schicchi’s insistent Dr. Spineloccio, William Grundler used his attractive tenor in decent service to a part that is often taken by a lower voice. As the old man representing Arithmetic (i.e. a page L’enfant has torn from a schoolbook) Mr. Grundler really lets loose with a vocal comeuppance that is as vocally satisfying as it is effortlessly funny.

Audrey Yoder’s hangdog Pinellino was a game stab at Puccini’s bass character, but hey, it worked. The soprano’s attractive timbre and laudable musicianship were much more fully on display in part two as a fussy Louis XIV chair, a pestering Bat, and a limpidly realized Shepherdess. Ms. Yoder had company covering minor male roles as Sarabeth Belóndid all she could as Guccio in the first opera. Happily, Ms. Belón’ shimmering, secure mezzo got a chance to shine in the second half as she ably essayed a squirming Squirrel and a serene Shepherd.

Well-remembered for her vocal acrobatics as POP’s recent Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute, Michelle Drever did not disappoint in her dual assignments of Fire and Nightingale. If anything, Ms. Drever’s melismas, leaps, and legato were now even more assured, and she imbued her vocalizing with fiery relish. This highly talented and evenly matched team of top area vocalists was buoyed by a polished band.

In the “pit,” Joshua Horsch led stylistically informed readings of two highly different sensibilities. Puccini’s boisterous Italian comedic effects, give way often to the plush lyricism that is his trademark. Ravel’s opus shows just why he is regarded as a master of orchestration, with more acerbic effects and a tendency to translucent tones, and vibrating harmonies. The outstanding group of musicians ably delineated these two works, thanks to Maestro Horch’s deft leadership.

I wish that the instrumental ensemble had indeed been in a pit, where their presence would have been on a par with the singers in Gianni Schicchi. Being off stage left sometimes rendered them hard to hear when the committed performers concertedly performed the extramusical wails the piece requires. Perhaps those outbursts could be modulated to allow the orchestra equal aural footing?

However, the balance for the Ravel was just the right mix of delicacy and brazenness that showed Mr. Horsch in complete command as he fused singers and instrumentalists into a luminous entity of sassy wonder and sheer delight.

This double bill is a sure-fire hit that will please the seasoned aficionado and curious novice alike. There is so much visual satisfaction and exceptional music-making going on here, that this should be one of the hottest tickets in town, and one of the most affordable. POP has taken the novel notion of pairing these two one acts for the very first time, and has emphatically turned it into a fully realized, wholly satisfying success.

James Sohre

Giacomo Puccini: Gianni Schicchi

Maurice Ravel: L’enfant et les sortileges

Gianni Schicchi/Black Cat: E. Scott Levin; Gherardino/Enfant: Kimberly Sogioka; Lauretta/Princess/Owl: Tiffany Ho; Rinuccio/Frog: Jonathan Matthews; Zita/White Cat: Sharmay Musacchio; Betto/Clock: Joel Balzun; Simone/Arm Chair: Tom Sitzler; Nella/Mother: Sonja Krenek; Ciesca/Teacup/Dragonfly: Danielle Marcelle Bond; Gherardo/Teapot: Robert Norman; Marco/Tree: Jared Daniel Jones; Amantio: Peter Barber; Spinelloccio/Arithmetic: William Grundler; Pinellino/Louis XIV Chair/Bat/Shepherdess: Audrey Yoder; Guccio/Squirrel/Shepherd: Sarabeth Belón; Fire/Nightingale: Michelle Drever; Conductor: Joshua Horsch; Director/Designer: Josh Shaw; Costumer: Maggie Green; Lighting Designer: Marie Scott Mawji; Director, Occidental Glee Club: Désirée La Vertu