February 27, 2020

A wonderful role debut for Natalya Romaniw in ENO's revival of Minghella's Madama Butterfly

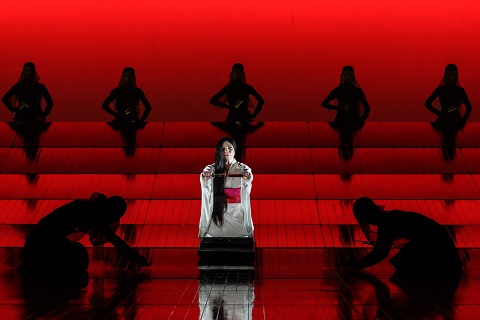

Before a note is played, a geisha’s silhouette emerges into the breath-held silence, etched against a carmine sky. She glides and floats, her fans fluttering decorously, glinting in the golden sun. As she raises her arms, her kimono flickers, as transparent as a butterfly’s veined wing. Her obi trails behind her, a blood-red bridal train. Scooped up by four dancers, the sash sculpts curving geometries which twist about the geisha, confining, restraining. When, in the opera’s final moments, Cio-Cio-San re-enacts her father’s fate, her wedding obi becomes a silk wound, seeping and swirling, a bloodless emblem of betrayal and transcendence.

Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Peter Mumford’s lighting pits complementary hues in eye-dazzling combinations. The ‘visual banquet’ that I admired in 2013 seemed an even more intensely piercing colour-feast on this occasion. Han Feng’s costumes heighten the quasi-theatrical strangeness of the sense-saturating world in which Pinkerton finds himself seduced. Surfeit is balanced with simplicity, though: the beige shoji that slide noiselessly, like sleights of hand; the tendrils of cherry blossom that dangle tender pink against the black night sky.

Natalya Romaniw and Blind Summit Theatre. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Natalya Romaniw and Blind Summit Theatre. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Then, there are the bunraku puppets, brought to life by the conjurer’s craft of members of Blind Summit Theatre. First time round, I’d found the puppets too stylised: a representation of the west’s ‘othering’ of the east. But, in 2016 I was won over by the truthfulness of the puppets’ uncanny realism, and here the mime-dance at the start of Act 2 Scene 2 foreshadowing Butterfly’s suicide was powerful and troubling. It was hard to believe that young Sorrow, dressed in a US Navy sailor-suit, rushing in stuttering steps to grasp his mother, tilting his head quizzically, proffering his hand to the saddened Sharpless, was not real.

Natalya Romaniw. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Natalya Romaniw. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

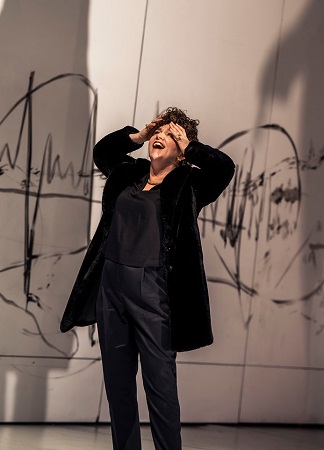

Singing her first Butterfly, Natalya Romaniw made a compelling entrance, the strong core at the heart of her shining soprano preceding her arrival at Goro’s marriage-brokering manoeuvres. Perhaps the creamy depths and heights of Romaniw’s soprano cannot quite capture the innocence of the fifteen-year-old ingenue, but the Welsh soprano worked hard to convey her naivety, and of Cio-Cio-San’s honour and pride, feistiness and gentleness, vivacity and vulnerability, there was no doubt. This Butterfly was bursting with a passion that she herself could barely know or understand. If I say that ‘Un bel dì vedremo’ brought I tear to my eye, I am not speaking figuratively. And, the ENO Orchestra, conducted by Martyn Brabbins, contributed greatly to the emotive power, so exquisite were the pianissimo gestures and textures. I had been underwhelmed by Brabbins’ approach in Act 1, but here understatement and delicacy were magically hypnotic, and thereafter there was more fire in the orchestral belly.

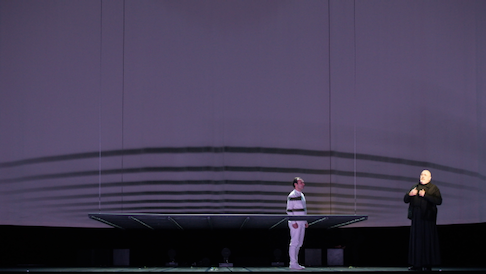

Dimitri Pittas and Roderick Williams. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

Dimitri Pittas and Roderick Williams. Photo credit: Jane Hobson.

American tenor Dimitri Pittas, making his ENO debut, was a rather clamorous Pinkerton, struggling at the top and compensating for lyricism with volume. The effect was to make Pinkerton, at least initially, even more of a cardboard villain than usual; though, more effectively, it also made the US interloper even more of a stranger in this foreign land. By Act 3, this Pinkerton’s uncomprehending bewilderment was more moving than I had anticipated.

The other members of the cast were accomplished but did not make much of a mark, excepting Roderick Williams who, as Sharpless, was brow-beaten by Pittas’ barking in Act 1, but who sculpted a flesh-and-blood figure of persuasive empathy and sensitivity in Act 2, his lovely soft baritone infusing his exchanges with Butterfly with humanising kindness. Stephanie Windsor-Lewis was a reliable Suzuki but did not convey the fierceness of her loyalty and love for her mistress. Alasdair Elliott’s well-defined tone and clean enunciation skilfully captured Goro’s contemptuous condescension. Keel Watson was a thunderous Bonze, Njabulo Madlala a rather wobbly Yamadori. Katie Stephenson completed the cast as a somewhat tentative Kate Pinkerton.

This was Romaniw’s night. And, there surely will be many more such nights.

Madama Butterfly continues in repertory until 17th April.

Claire Seymour

Cio-Cio San - Natalya Romaniw, Pinkerton - Dimitri Pittas, Sharpless - Roderick Williams, Suzuki - Stephanie Windsor-Lewis, Goro - Alasdair Elliott, The Bonze - Keel Watson, Prince Yamadori - Njabulo Madlala, Kate Pinkerton - Katie Stevenson; Director - Anthony Minghella, Revival Director - Glen Sheppard, Conductor - Martyn Brabbins, Set Designer - Michael Levine, Lighting Designer - Peter Mumford, Costume Designer -Han Feng, Associate Director/Choreographer - Carolyn Choa, Revival Choreographer - David John, Puppetry - Blind Summit, Chorus and Orchestra of English National Opera.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Wednesday 26th February 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/MB%20ENO%20title%20image.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Madama Butterfly at English National Opera product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Madama Butterfly, English National Opera

Photo credit: Jane Hobson

February 26, 2020

Charlie Parker’s Yardbird at Seattle

An assiduous scour through past reviews and You-Tube videos confirms that it has changed very little since it was reviewed for Opera Today at its opening by Andrew Moravcsik .

Curiously, its most detailed and analytical critique appeared in the official journal of jazz Downbeat, when that journal’s Chicago correspondent Howard Mandel reported on the two performances presented by Lyric Opera in its smaller Kimmel Theatre venue.

Or is it curious? Mandel was able to approach the piece from neutral ground, unconstrained by the burdens facing “classical” and “opera” reviewers covering a piece not only outside the standard repertory but outside in subject matter: the life and work of a hugely gifted drug-addicted black jazz improvisor who dreamed about fusing his art with mainstream classical music.

Chrystal E. Williams (Rebecca Parker)

Chrystal E. Williams (Rebecca Parker)

In his Downbeat write-up Mandel acutely analyses the components of composer Daniel Schnyder’s third-streamy amalgam of buried references to works by Parker and other jazz and classical composers, and the way that his busy, buzzy orchestration often blurs and distracts from his angular quasi-tonal vocal lines.

He doesn’t dwell on its effect on the singers and the audience. To penetrate the background instrumental muttering, the performers have to declaim every line, pedestrian or pompous; and since their material is undifferentiated and chanted at the same ponderous pace throughout, it soon ceases to have any particular emotional impact.

The thermostat is set at fraught. Each scenelet blurs into the next as the cast moves from one cafe table to another to denote the passage of time, forward and back. Dead at curtain’s rise, Parker revisits youth, fame, degradation, friendship, romance, only to end up on the same gurney they rolled him in on 90 intermissionless minutes before, while the remaining cast take turns mourning over him and the alto sax he brandishes from time to time but never plays.

The Seattle cast copes well with the material provided. The lights go on and off, the set goes up and down, time passes. The show ends. The compulsory standing ovation ensues. Curtain.

Roger Downey

Charlie Parker’s Yardbird : libretto by Bridgette A. Wimberly; music by Daniel Schnyder. Charlie Parker: Joshua Stewart/Frederick Ballentine; Addie Parker: Angela Brown; Rebecca Parker: Chrystal E. Williams; Doris Parker: Jennifer Cross; Chan Parker: Shelly Traverse; Dizzy Gillespie: Jorell Williams; Baroness Kathleen Annie Pannonica de Koenigswarter Rothschild: Audrey Babcock. Original stage director: Ron Daniels; Settings: Riccardo Hernandez; Costumes: Emily Rebholz; Lighting: Scott Zielinski; Choreoraphy: Donald Byrd; Sound design: Robertson Witmer. Members of the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, Kelly Kuo, conductor.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/200219_YardBird_DR_%201728.png image_description=Joshua Stewart (Charlie Parker) & Jorell Williams (Dizzy Gillespie). [Photo by Philip Newton] product=yes product_title=Charlie Parker’s Yardbird at Seattle product_by=A review by Roger Downey product_id=Above: Joshua Stewart (Charlie Parker) & Jorell Williams (Dizzy Gillespie).All photos by Philip Newton

February 25, 2020

La Périchole in Marseille

Then there is Patrice Munsel who re-created the role for soubrette soprano for the Metropolitan Opera’s grand opera version back in the 1950’s. Never to be forgotten is Maria Ewing’s delightful Périchole in San Francisco Opera’s spring season at the Curran Theatre back in the 1970’s. And of course Stephanie d’Oustrac who triumphed in the role at the Opéra de Marseille in 2002.

It is good news indeed that Marseille may have discovered a Périchole for a new generation. Already on her way to becoming an Offenbach diva mezzo soprano Héloīse Mas recently sang stage director Laurent Pelly’s bratty Boulotte (Barbe-Bleue) on the main stages in Lyon and Marseille. Just now Mlle. Mas found herself on the Opéra de Marseille’s second stage, the Théâtre de l’Odéon de Marseille (a 1928 cinema updated to an 800 seat “boulevard” style theater) for a somewhat reduced La Périchole.

Not that the Périchole of Mlle. Mas was in any way reduced. She approaches the mold of a larger than life diva, radiating a huge personality. It is a bonus that she is a fine singer who sang the role in big, warm and confident mezzo voice. This young artist (32 years old) may be capable of finding a far greater subtlety of character in this role than she projected, though she did create a charming, big-eyed mock innocence that all too often usurped the small stage.

Pedrillo was sung by tenor Samy Camps who brought everything needed to create Perichole’s easily duped, hapless lover. He is charming, young and fun and sings well. He has carved himself a career bringing new life to long forgotten Offenbach lovers in the Opéra de Marseille’s Offenbach Project, and to delighting France’s regional operetta audience in revivals of once famed works like composer Herzé and librettist Henri Meilhac’s comédie-vaudeville, Mam’zelle Nitouche.

The balace of the cast, notably the Viceroy sung by Olivier Grand and the Old Prisoner sung by Michel Delfaud, comes from the Opéra de Marseille’s (and the south of France’s) rich treasury of operetta and character singers.

The Can-Can, with wigged chorus

The Can-Can, with wigged chorus

The production was staged by Marseille born Olivier Lepelletier. Mr. Lepelletier organized a minimal set that made the most of the minimal stage space of the Odéon, erecting four steps up across the back of the state, the center of which was a tiny, curtained proscenium opening, making the scene the cabaret of the three cousins. Minimal adjustments were made to create the second act palace (the chorus was sumptuously costumed) and the third act jail (a couple of benches downstage). Director/designer Lepelletier used the conceit of weird wigs that echoed a bit the idea of the exaggerated costuming of the 1868 Théâtre des Varietés production.

It was absolutely plenty to set the stage where Offenbach’s musical antics to the charmed antics of his famous librettists, Meilhac and Halévy triumphed without distraction. It was done with an orchestra of twenty players in the Odéon’s minimal pit. Conductor Bruno Membrey gave the accomplished performers everything they needed to show off their considerable personalities. It was the pure Offenbach at his minimal, maybe maximal, indeed very pleasurable best.

Mr. Lepelletier incorporated Offfenbach's 1874 version in so much as he could in his reduction of production requirements, modifying the narrative a bit in the first act to accommodate its placement in the cabaret, gently mocking the clergy as well.

Of great amusement were the four leg-some dancers, one of whom, Esméralda Albert, was the choreographer. They were the acrobats of the first act, the high kicking legs somehow avoiding a massacre of the chorus. They then became the guards who hustled Pedrillo and Périchole off to jail in jolly synchronized steps, a very charming moment.

It all climaxed in a rip roaring can-can à la Moulin Rouge, with the contortionist dancer, Adonis Kosmadakis, joining the four propelled danseuses to blow us away (it's hard to see the legs in the photo, but they're there).

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

La Périchole: Héloïse Mas; 1ère Cousine / Guadalena: Kathia Blas; 2ème Cousine / Berginella Lorrie Garcia; 3ème Cousine / Mastrilla: Marie Pons; Piquillo Samy Camps; Vice-Roi Olivier Grand; Panatellas Jacques Lemaire; Hinoyosa Éric Vignau; Tarapote / Un Notaire Antoine Bonelli; Le Vieux Prisonnier / Un Notaire Michel Delfaud. Chœur Phocéen; Orchestre de l’Odéon. Direction musicale Bruno Membrey; Mise en scène Olivier Lepelletier;

Chorégraphe Esméralda Albert. Théâtre de l’Odéon de Marseille, February 23, 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Perichole_Marseille3.png

image_description=Photo by Christian Dresse courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille

product=yes

product_title=La Périchole in Marseille

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Samy Camps as Pedrillo, Héloīse Mas as Périchole

Photos by Christian Dresse courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille

February 23, 2020

Three Centuries Collide: Widmann, Ravel and Beethoven

We began this journey through time in 2003 with Jörg Widmann’s Lied for Orchestra. This is a piece centred on melody - and centred on Schubert. It is a work of profound extremes, with an orchestra that is like a Schubert lieder but without being the accompaniment to it. The tenor of the music is indeed more resonant of Schubert than Widmann’s style normally suggests, and if there is a focus on song in this piece it is generated by the orchestra responding to the intimacy of the instrumentation of a piece like the Octet with instruments characterised by instrumental solos replicating their orchestral voices. But, what is also noticeable is what is not Schubert. The debt to Sibelius - especially that composer’s Seventh Symphony - shines like a floodlight. Even more apparent is Mahler’s Tenth Symphony, especially the final movement. The use of the bassoon suggests all its lugubriousness, but it’s the intensity of the string writing, the swelling violins and dark strings which seem just as searing in that movement’s terrifying climax; a trio of trombones has all the effect of overloaded power, the crushing percussion a hammer blow. The work may travel through styles but it’s musically effective and the London Philharmonic played it superbly.

Wind back a century to 1903 and we were in the world of evocative song and ravishing orchestration - Ravel’s Shéhérazade. This was, in many ways, not an ideal performance but Ravel does not make life particularly easy for any mezzo who attempts to sing the part. Christine Rice lacked a certain precision in her French which was magnified, certainly by this particular orchestra. When Juliette Bausor’s principal flute sounded so impeccably shaped, with a tone exquisitely given to stretch her lines into infinity, Rice’s clipping of phrases and tendency to muzzle the distinctive clarity of what she was singing came across as less than accurate.

But that is not to say that her voice itself is often a beautiful instrument. Its very depth and sheen can often give the impression of conveying mystery, although what we got was principally an illusion of it. That long first song, ‘Asie’, should be a melding of two worlds - one of beauty the other of horror; but listening to Rice’s version I’m not sure I got this. There didn’t seem much of either mystery or solitariness in the line “Mystérieuse et solitaire”, nor the distinction between “des rose et du sang” towards the songs close. The panache of the London Philharmonic’s Spanish-inflected rhythms, its oriental shades of Eastern promise were highly expressive but simply highlighted the struggle many singers experience in this cycle.

There are difficulties in the two shorter songs, though I think Rice managed them slightly better. ‘La flute enchantée’ needs to strike a balance between sorrow and joy and that is largely what we got with Rice able to bring a mellowness and sense of radiance to her voice. ‘L’indifférent’ is complex in that it can take a mezzo outside her comfort zone - some find the characterisation of its androgyny difficult to navigate; others embrace it. Rice leaned towards the latter, but principally because the voice’s darker more masculine tones hinted at her ambiguity.

Dima Slobodeniouk. Photo credit: Marco Borggreve.

Dima Slobodeniouk. Photo credit: Marco Borggreve.

The concert ended in 1803, as it were, with Beethoven’s Eroica. Despite this symphony being an indisputable masterpiece, it never surprises me how many performances of it hang fire. This, however, was one of the most incendiary I have heard in many, many years. I have yet to mention the conductor of this concert, Dima Slobodeniouk. He is not the most precise conductor I have seen, but what he does do is shape what he conducts with great integrity and vision. The gestures are broad in scope as he sweeps his left hand deep into the orchestra. But what is most impressive is that magical illusion of making what he conducts seem much faster than it actually is. The Allegro con brio of this Eroica sounded quite measured but the sheer electricity generated was absolutely thrilling. There was no broadness in those opening chords, so I suppose one might have expected a certain fleetness - but it wasn’t immediately apparent we would get it.

The Marcia Funebre, on the other hand, seemed to work in the opposite direction. This was fast, and there was never any sense it was otherwise. Perhaps the F minor Fugue didn’t quite have sufficient power for my taste, but Slobodeniouk managed to pull some depth from the LPO’s cellos and basses which did at least suggest gravity and that plunge into the turbulent and ferocious development was a thrilling cataclysm of despair. I think one might have preferred divided violins and a different layout of lower strings, but we had what we had.

The brilliance of this performance’s Scherzo was entirely down to the lightness of touch from the orchestra, something which was carried through to the Allegro molto - its storms, fugues, sforzandos and wildly fluctuating dynamics articulated with uncompromising brilliance. A revelatory performance, and one which bookended an often fascinating concert.

Marc Bridle

Christine Rice (mezzo-soprano), Dima Slobodeniouk (conductor), London Philharmonic Orchestra

Royal Festival Hall, London; Saturday 22nd February 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Christine-Rice-4bw-c-Patricia-Taylor-WEB%20%281%29.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Dima Slobodeniouk conducts the London Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Festival Hall product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=Above: Christine RicePhoto credit: Patricia Taylor

Seventeenth-century rhetoric from The Sixteen at Wigmore Hall

Published in 1593, Henry Peacham’s The Compleat Gentleman reminds us of one of fundamental philosophical and cultural tenets of the Elizabethan age: the close, perhaps inextricable, relationship which was held to exist between the art of music and the art of spoken rhetoric. And, it was that bond of music and word - which composers exploited to ‘move’ the listener by cultivating grief, melancholy, joy and faith - that this programme of music presented by The Sixteen at Wigmore Hall was designed to reflect.

But, the self-conscious rhetoric of the lute ayre, with its quasi-metaphysical tensions and its strange intensity and elusiveness, is quite a different thing from the nature of the musico-poetic relationship that we see William Byrd crafting in his 1611 collection, Psalmes, Songs and Sonnets. When Byrd declares his music as being ‘framed to the life of the words’ he does not mean that his songs are a musical embodiment of a poem’s central conceits, such as we find in John Dowland’s 1612 collection, A Pilgrimes Solace. Byrd is concerned not with elusiveness but with clarity; his music reinforces the formal contours of the poetry which thereby acquires a rhetorical force so that the listener may appreciate its meaning more directly and powerfully. The Sixteen, led by their conductor Harry Christophers, proved more comfortable exploring Byrd’s expressive formal rhetoric and madrigalian detail than Dowland’s illusive tropes and dialectic.

The items by Dowland offered individual singers an opportunity to step from the ensemble and perform as soloists, accompanied by lutenist David Miller. Soprano Katy Hills sang ‘Disdain me still’ with directness, purity of tone and some attentiveness to the words, but her delivery lacked the flexibility required to convey the erotic tension of the text which opposes desire’s fulfilment with its self-destruction: “Disdain me still, that I may ever love”, begins the poet-singer, concluding, “Love surfeits with reward, his nurse is scorn”.

These songs require considerable performative presence. Perhaps the presence on the platform of the other singers and Christophers, the latter perched on a high stool, was inimical to the recreation of the intimate context for which these courtly songs - intended for a specific, intellectually sophisticated and socially elevated status - were composed. That said, the ensemble was necessary for the choric conclusions to ‘Welcome black night’ and ‘Cease these false sports’, which suggest that these songs were performed within a masque or similar entertainment. The florid melismas of the latter were elegantly sung by bass Ben Davies, although he did not communicate the nuances and inferences of the text, which he articulated clearly, as the poet-speaker bids “Goodnight” to his “yet virgin bride”. Jeremy Budd’s tenor was fittingly light and buoyant in ‘Up merry mates’, though in characteristically melancholy fashion, Dowland concludes with a minor-key choral lament, “A dismal hours,/ Who can forbear,/ But sink with sad despair.”

Alexandra Kidgell revealed the richly colour lower register of her soprano at the start of ‘In darkness let me dwell’, but she seemed uncertain how to negotiate the irregularity of Dowland’s phrase structures and his inventive approach to text setting which capture the idealisation of sorrow and death in these elegiac ayres, embodying as they do the notion of inexpressibility and the dissimulation, concealment and ambivalence which are the essence of the courtly pose.

The stillness and serenity of soprano Julie Cooper’s performance of ‘Sweet stay awhile’ was compelling, and bass Eamonn Dougan made much of the repetition of the final couplet of ‘Shall I strive with words to move’: “I wooed her, I loved her, and none but her admire./ O come dear joy, and answer my desire.” Here there was a real sense of human complexity, contradiction and desire. The Dowland songs were accompanied in a rather restrained manner by Miller, tasteful and no doubt idiomatic, but with little sense of the mercurial and ‘strange’ that more elaborate renditions may intimate. Miller and tenor Mark Dobell had the stage to themselves for a sequence of three songs, ‘Thou Mighty God’, ‘When David’s Life by Saul’ and ‘When the poor cripple’. Dobell’s soft even tone was apparent from the first unaccompanied “Thou”, and the vocal line was well-focused as it twisted through the chromatic contortions and the aching repetitions of “misery and pain”.

The members of The Sixteen seemed more comfortable singing as an ensemble, and the idiom of William Byrd’s Psalmes, Songs and Sonnets, ‘Some solemne, others ioyfull, framed to the life of the words: fit for voyces or viols of 3.4.5. and 6. parts’, is a natural fit for Christophers’ approach to words, rhythmic form and temporal expression.

There was a gradual heightening of intensity in the opening ‘Retire, my soul’, while the ever denser textures of ‘Come woeful Orpheus’ were beautifully strengthened by the eloquence of the middle voices, culminating in the urgent chromaticism of the closing appeal: “Of sourest sharps and uncouth flats make choice,/ And I’ll thereto compassionate my voice.” A ‘wiry’ nimbleness characterised ‘Come, let us rejoice unto the Lord’ and this energy swept through and beyond the final phrase, Christophers briskly snatching away the concluding avowal, “in psalms let us make joy to him”. The way Byrd’s uses formal rhetoric to communicate verbal, often moral, meaning was well-illustrated at the close of ‘Arise Lord into thy rest’, the melismatic ‘leans’ of “Let the priests be clothed with justice ” being sharply superseded by the staccato dance, “And let the saints rejoice”.

I found some of the lighter lyrics presented in the second half - ‘Sing we merrily’, ‘Come jolly swains’ - a trifle too tinged with the diction and tone colour of the English cathedral school tradition; but, ‘This sweet and merry month of May’ had lovely flexibility, the triple-time “pleasure of the joyful time”, giving way to the expansive awe and adulation of “ O beauteous Queen”, before a celebratory surge to the close. The “Amen” at the end of ‘Praise our Lord all ye Gentiles’ was warm and florid, opening its petals like a budding flower releasing its scents and welcoming the sunlight. Some of the ensemble songs were accompanied by Miller but, at least from my seat at the rear of Wigmore Hall, the lute was practically inaudible.

‘This day Christ was born’ had made for a buoyant conclusion to the first half of the concert, “rejoice” blossoming melismatically before a majestic “Glory be to God on high” was answered by a triple-time “Alleluia”. Christophers manoeuvred the structural and temporal shifts with masterful control and ease. Similarly, the seamless polyphony of the final item of the concert, ‘Turn our captivity, O Lord’, built persuasively towards the confident assertion, “they shall come with joy”, and the broad assurance, “carrying their sheaves with them”.

Claire Seymour

The Sixteen: Harry Christophers (conductor)

Byrd - ‘Retire my soul’; Dowland - ‘Disdain me still, that I may ever love’; Byrd - ‘Come woeful Orpheus’; Dowland - ‘Welcome black night/Cease these false sports’; Byrd - ‘Come, let us rejoice unto our Lord’, ‘How vain the toils’, ‘Arise Lord into thy rest’; Dowland - ‘Thou mighty God’; Byrd -‘Make ye joy to God’, ‘This day Christ was born’, ‘Sing we merrily’; Dowland - ‘In darkness let me dwell’; Byrd - ‘Come jolly swains’; Dowland - ‘Up merry mates’; Byrd - ‘Crowned with flowers and lilies’; Dowland - ‘Sweet stay awhile’; Byrd - ‘This sweet and merry month of May’; Dowland - Preludium, ‘The Frog Galliard’; Byrd - ‘Praise our Lord, all ye Gentiles’; Dowland - ‘Shall I strive with words to move’; Byrd - ‘Turn our captivity, O Lord’

Wigmore Hall, London; Friday 21st February 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Harry%20Christophers%20High%20Res%202%20-%20credit%20Marco%20Borggreve.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Sixteen sing Dowland and Byrd at Wigmore Hall product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Harry ChristophersPhoto credit: Marco Borggreve

Hrůša’s Mahler: A Resurrection from the Golden Age

There was, it should be said, nothing intimate about Hrůša’s opening bars;

the abundance of dynamic power here was terrifying and yet it was played

with a gripping conviction and intensity which would be a hallmark of this

performance. There are performances of Mahler’s Resurrection which

lapse - rather quickly, and all too commonly - into fragments. This was not

one of them. Hrůša does see contrasts in the first movement, but they

aren’t noticeably extreme. We never got a heavy-handed treatment of the

woodwind during their first theme; their rhythms were pointed and

eloquently sketched rather than chiselled into stone. That Hrůša was able

to take this vast movement in one long sweep never concealed the urgency or

dramatic intensity of the furious and wild ride he and the orchestra took

us on.

It was the second movement’s Andante which demonstrated either

considerable preparation for this performance, or just a symbiosis of

vision between the conductor and orchestra. Whichever it was, it was simply

remarkable. I have rarely encountered this movement performed with such

delicacy or care for its inner details; hanging on each note but with such

fluidity - but then Hrůša’s Czech background takes us very close to the

Mahlerian roots of Austrian Ländler and waltzes where these things matter.

Woodwind solos weren’t just phrased like mini dramas, each individual

instrument was like the dramatis personae in a play; it was crystal clear

what each instrument was doing (the chamber music quality of this

performance) and you never questioned even the smallest details. The

pizzicato section had no unexplained deviations; and you knew exactly

whether the harp was playing an arpeggio or otherwise.

Hrůša’s Scherzo lacked none of the fear or horror which he had

brought to the first movement. One often wondered from what hell the

resonating and thundering timpani came from; but they were the support or

markers for a tempo which had a swiftness that was electrifying. Hrůša is

not a conductor to feel the fear of Mahler’s pianissimos - we got it during

the main subject here. The lingering, evocative, bassoon of Emily Hultman

appeared like a spectral presence through the undergrowth of the orchestra,

just as a fluttering trio of flutes wavered and floated above the

Philharmonia’s gutsy strings. Brass were so precise they seemed like

soldiers marching in unison.

Urlicht

really was uncommonly rapt here, perhaps a surprise given how powerful the

first three movements of the symphony had largely been. Hrůša didn’t so

much take the orchestra into quieter territory but pulled them down like a

force of nature. I think it made Jennifer Johnston all the more sumptuous

because of that, her voice seeming just a little larger than life and we

usually experience in this movement. The darkness of her tone, those plump

lower notes with a beautifully supported upper range which floated

exquisitely mirrored so much of what Hrůša had been doing with the

orchestra. That depth in Johnston’s bottom register was articulated on the

lower strings; she was always involving, the Philharmonia never elementary.

After such rapture the outburst to the final movement seemed shocking.

Hrůša held nothing back, unleashing the Philharmonia with such power it

felt like the prelude to an execution. You sometimes sense fatigue in

orchestras during this vast monument - here, if anything, the Philharmonia

were driven by its ferocity, inspired by Hrůša’s vision of its immensity

and scale but also of its visceral, juggernaut-like drive. The Royal

Festival Hall is often criticized for its acoustic but in such large-scale

works as Mahler’s Resurrection this hall works to its advantage.

This was particularly the case during the off-stage bands, those eccentric,

even malevolent, distractions. Here they felt like rapid, intoxicated and

riotous interludes, although just occasionally one felt that Hrůša brought

such power to the orchestra they were simply overwhelmed. But off-stage

trumpets were magnificent and as sharp as knives in their accuracy.

The soprano Camilla Tilling did not start her first entry well, sounding

both underpowered and very uncertain as to whether her voice would stretch

to its required range. The first entry of the chorus - on such a diminished pianissimo - was ravishing, audible enough, but one almost had to

strain to hear them. If Johnston had the power to rise above the orchestra,

Tilling still struggled somewhat, not always helped by a variable vibrato

which strained rather than helped her voice. I’m not really sure they gave

the most balanced of duets I have ever heard in this symphony either. It

was only really before the chorus’s forte entry that Tilling

finally assumed some power but it felt too late. And the chorus were

magnificent, even cataclysmic, the clarity of the diction almost irrelevant

given the sheer scale of its climax. Hrůša brought that final orchestral

peroration to a close with its breadth of emphasis rather than the usual

clipping of the phrase.

This had been a superlative Mahler Resurrection, a gripping

performance in an age where it is rare to experience Mahler of this

quality.

Marc Bridle

Camilla Tilling (soprano), Jennifer Johnston (mezzo-soprano), Jakub Hrůša

(conductor), Philharmonia Chorus, Philharmonia Orchestra

Royal Festival Hall, London; Thursday 20th February 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Jennifer%20Johnston%20%C2%A9%20R%20T%20Dunphy.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Mahler: Symphony No.2 (Resurrection) product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=Above: Jennifer JohnstonPhoto credit: R.T. Dunphy

February 20, 2020

Full-Throated Troubador Serenades San José

A wagging singsong parody of the knotty plot begins with “I’ll tell you the story of Il Trovtore.” One reason for the difficulty in following the nefarious machinations is that most of the all-important set-up has happened off stage, well before the opera’s story ever begins. So, it behooves audiences to pay particularly close attention to the Surtitles during the opening scene when the rivalry for Leonora between Manrico and the Count di Luna is explained, the introduction to the trials of the gypsy woman Azucena is laid out, along with the suggestion of a terrible secret.

Brad Dalton has chosen to stage a pantomime during the opening bars that establishes di Luna’s unholy lust for Leonora and her understandable revulsion. Mr. Dalton has staged a non-fussy, straightforward account that was admirable for its clarity and control. Stage pictures were clean and varied, although they (only) occasionally suffered from a bit of stasis.

If the characters were longer on potent vocal delivery than they were on richly detailed interaction, that is not entirely the responsibility of the director. Mr. Dalton managed to infuse sufficient life in the sometimes illogical twists and turns of Cammarano’s routine libretto to make it understandable and engaging. He even provided some compelling novel touches like having an emboldened Leonora pair with her Manrico at the close of Act I by brandishing a broadsword as if to the mission born.

Manrico (Mackenzie Gotcher) comforting his true love, Leonora (Kerriann Otaño).

Manrico (Mackenzie Gotcher) comforting his true love, Leonora (Kerriann Otaño).

Much of OSJ’s marketing of this feature furthers a Game of Thrones dynamic, banking on that enormously popular show to help sell tickets to new audiences. The association is not misplaced, since power playing is what drives the plot. In epic fashion, the ubiquitous sword is passed and paraded ceremoniously from scene to scene, and what a satisfying scene design it is.

Steven Kemp has devised a winning variation on the “unit setting” concept, framing the space with brick legs and tormentors that not only convey imposing structures when required, but also literally frame the action with handsome detail. Within this basic look, Mr. Kemp moves about stylish steps, anvils, ramps, anvils, and well-selected set pieces that are backed by a distressed backdrop that sports a jagged rounded hole, like the outline of an oozing planet, up left.

Michael Palumbo has lit the proceedings with aplomb and colorful imagination, capitalizing on many different variations of the exclusively nighttime action of the piece. Mr. Palumbo’s areas and specials were all moody evocations of the tortured progression of the characters’ journeys. Curiously, the glow of the oncoming dawn in Act II receded to shadows for the powerful Azucena-Manrico exchange, murkily effective, but not exactly how dawn works.

Elizabeth Poindexter’s sumptuous, abundant array of costumes not only delighted the eye but also commendably informed the station of the characters. Ms. Poindexter was ably abetted by Dave Maier’s telling wig and make-up design, which complemented the historical fantasy concept. I might have wished for a more eccentric, troubled, gypsy look for Azucena, but I respect the committed decisions the team made.

Leonora (Kerriann Otaño) who, believing her love has died, prepares to take the veil and enter a convent.

Leonora (Kerriann Otaño) who, believing her love has died, prepares to take the veil and enter a convent.

Enrico Caruso famously quipped the “all you need for a successful production (of this opus) is the four best singers in the world.” Even the world’s major houses are challenged to meet the starry demands of Il Trovatore, but if you want to know who the next major international proponents of these roles will likely be, you need not look much further than the skillful assemblage on stage at the California Theatre.

It is called The Troubador after all, and Mackenizie Gotcher was simply tremendous in the titular assignment. Mr. Gotcher is perfectly equipped to excel in the challenging role of Manrico, with his strapping good looks, ringing heavy lyric tenor, and consummate musicality. There is no aspect of this daunting assignment that eludes him, be it the stentorian thrills of “Di quell pira,” the honeyed sentiments of “Ah! si ben mio,” or the gripping exchanges with Azucena.

Gotcher has true squillo in his sizable instrument, and he lavishes Verdi’s potent writing with personality and deeply felt emotions. The road ahead seems bright indeed for this polished, poised performer. His star turn alone is worth the price of admission. Happily, he is in good company.

Mezzo Daryl Freedman is on her way to becoming a force of nature in the Zajik mold with her powerful, knowing interpretation of the willful Azucena. Ms. Freedman’s well-schooled instrument was even from top to bottom, and she knows how to knit her registers with consummate skill. With a rich, ripe middle range, a searing, pliable top, and round, booming chest tones, this treasurable vocalist found every variation of intensity in the opera’s most complex role. I hope that future outings will find this gifted interpreter delving even deeper into the dramatic subtext.

Ferrando (Nathan Stark) ordering his men to keep watch.

Ferrando (Nathan Stark) ordering his men to keep watch.

Eugene Brancoveanu is a mellifluous, malevolent Count di Luna. His baritone is a marvel of tonal beauty, buzzing with virility, and eminently flexible. Mr. Brancoveanu invests the many repetitive confrontational declamations with admirable delineation, and he avoids the trap of barking the accented scale and arpeggiated passages. He displays enviable ease in the upper reaches of the part and finds some welcome brighter swings in the Count’s mostly dark intentions.

I only wish that this fine singer could find a bit more breath control for the Bellinian stretches of his character-defining aria, for I found that his choppy phrasing and snatched breaths somewhat defeated the beauty of the long-drawn lines of “Il balen.” Most everywhere else he excelled, no more so than in the well calibrated last act duet with Leonora, the accomplished performer Kerriann Otaño.

Ms. Otaño’s warmly radiant, substantial soprano was a lovely complement to the roster. Her Verdian sense of line and her deeply experienced, conflicted feelings were manifest in a role traversal that was long on beautifully modulated tone and knowing generosity of utterance.

Like many a famous interpreter of this difficult assignment, once past the pitfalls of successfully negotiating “Tacea la note placida” and its angular cabaletta, the soprano relaxed into a luxuriant outpouring of sound and sentiment that dominated her every appearance. Her defiant, armed stance against Manrico’s opponents spoke volumes about the depth of her theatrical resolve.

Although Caruso addressed the demands for the four principals, there is a fifth requirement for a fine Trovatore, namely Ferrando, who has the unenviable job of setting up the whole unlikely scenario in his lengthy opening appearance. Luckily, local favorite Nathan Stark conquered in that daunting responsibility, and he delivered in spades, with a potent and pointed delivery of “Di due figli.”

Mr. Stark has a sizable, pliable bass-baritone that limns the tale of two rival brothers with tragic urgency. Moreover, he commands the stage with a winning presence and cunning command of nuance. It is not often that you will encounter this opening scene invested with such artistry and dramatic interest. He is greatly assisted in his efforts by the excellent exclamations from Christopher James Ray’s well-tutored chorus, who were outstanding all evening long.

A final vital component in the evening’s success was Joseph Marcheso’s conducting of a responsive and highly skilled orchestra. Maestro Marcheso displayed full command of this almost bare bones structure of the middle Verdi canon, and he managed to invest the repetitive bass-chord-bass-chord progressions with meaningful forward motion. He also partnered his vocalists with consummate collaborative effort, even though the soloists sometimes lagged just a bit behind the beat in more urgently rapid passages.

At the end of the night, the excitable opening night audience was clearly delighted with the riveting music making and lavished the performers and creative team with a vociferous appreciation. This winning mounting of Il Trovatore is not only top professional quality, but it is also excellent entertainment value at Opera San Jose’s reasonable pricing. Come to the California theatre early and you may also get treated to a pre-show pops recital on the historic organ in the atmospheric lobby.

James Sohre

Il Trovatore

Music by Giuseppe Verdi

Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano

Leonora: Kerriann Otaño; Manrico: Mackenzie Gotcher; Count di Luna: Eugene Brancoveanu; Ferrando: Nathan Stark; Azucena: Daryl Freedman; Inez: Stephanie Sanchez; Ruiz: Mason Gates; Old Roma: Glenn Louis Healy; Messenger: Nicolas T. Gerst; Conductor: Joseph Marcheso; Director: Brad Dalton; Set Design: Steven Kemp; Costume Design: Elizabeth Poindexter; Lighting Design: Michael Palumbo; Fight Choreography: Dave Maier; Wig and Make-up Design: Christina Martin; Chorus Master: Christopher James Ray.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Il-trovatore_David-Allen_6-scaled.png image_description=Azucena, (Daryl Freedman) describing to Manrico (Mackenzie Gotcher) her most tragic misdeed. [Photo by David Allen courtesy of Opera San José] product=yes product_title=Full-Throated Troubador Serenades San Jose product_by=A review by James Sohre product_id=Above: Azucena (Daryl Freedman) describing to Manrico (Mackenzie Gotcher) her most tragic misdeed.All photos by David Allen courtesy of Opera San José

February 19, 2020

Opera North deliver a chilling Turn of the Screw

Ambiguity lies at the heart of Henry James’s ghost story, a tale that’s grist to the mill for imaginative directors, especially those willing to add new layers of suggestion. James’s novella is far more than the blurred lines arising from the presence of ghostly apparitions (made explicit here) or the absence of moral absolutes. It’s a world of half lights and shadows (thanks to Matthew Haskins’s atmospheric lighting effects) and tacit implications which, under Alessandro Talevi’s insightful direction, invite even more disturbing interpretations. Myfanwy Piper's libretto (disappointingly rendered without the benefit of surtitles) and Britten’s perfectly matched music insinuates itself into our collective consciousness, which, to borrow from the original Prologue, “won’t tell … in any literal, vulgar way”.

Madeleine Boyd’s Gothic-influenced, semi-lit set (a bedroom cum nursery somewhere in the 1920s) is furnished with a four-poster bed, rocking horse and writing desk with surrounding Romanesque portico, elevated turret and opaque church windows. Within Bly’s gloomy mansion a new governess is entrusted to educate two orphaned children Miles and Flora whose souls are ‘taken’ by the ghosts of a servant and a previous governess. Should we believe the children are possessed by evil spirits or tarnished by abuse? To what extent does the Governess herself want to possess the children, not just protect them?

Like the church windows, nothing is clear, yet Talevi ramps up the work’s sinister malevolence with more than a hint of sexual nuance - its presence only veiled by the author but here implicit not just by the presence of the stage-dominating bed but through the interactions of the protagonists. Above its covers Flora manipulates puppet versions of Miss Jessel and Peter Quint whose actions leave little to the imagination, a half-naked Miles slides between the sheets suggestively after forcibly kissing the Governess at the close of Act One, and by the same bed she and Mrs Grose have a lingering embrace just a little too long not to raise eyebrows. If that’s not enough, a visibly pregnant ghost of Miss Jessel appears to have lesbian eyes for the Governess.

This “anxious girl out of a Hampshire vicarage” is played and sung with much subtlety by Sarah Tynan. Her increasing trauma is clear, but at times there could have been more dramatic presence. Emotionally derailed by the first appearance of Nicholas Watts’s corrosive Peter Quint, she goes n to make a believable portrayal of vulnerability and meets Britten’s vocal challenges with fulsome tone, delivering a moving rendition of the letter-writing scene (its lush music clearly indicative of her feelings for the children’s uncle).

Nicholas Watts sets the standard vocally with a burnished account of the Prologue, the composer tellingly accompanying his chilling yearnings for Miles with bright celeste tones which simultaneously appeal and repel. Watts co-conspirator Eleanor Dennis is a compelling Miss Jessel, forming a superb partnership in the “Ceremony of Innocence” duet. Heather Shipp excels as the naive and over-burdened Mrs Grose, bringing to the role ample tones and a strong presence, her nerves calmed by a hip flask following the initial revelations about Quint.

Jennifer Clark and Tim Gasiorek are both well defined as the children, outwardly charming, but able to unsettle the most robust of Governesses. Their traversal from blameless innocents to wily conspirators is wholly convincing as are well-matched voices that impress memorably in Act Two’s “Benedicite”. Less convincing is the absurd dance movements given to Gasiorek here replacing the usual piano practice scene. Perhaps most unnerving is the closing encounter between him and an identically dressed Quint doing battle for this soul where the sense of menace reaches well beyond the stage.

Below stage the thirteen instrumentalists of the Orchestra of Opera North deliver alert and well projected playing under Leo McFall’s efficient direction. Details will sharpen up in time, but this opening night held considerable promise for forthcoming performances. The production is to be streamed ‘live’ from the Grand Theatre onwww.operavision.eu on Friday 21 st February and will be available to view for a further six months.

David Truslove

Britten: The Turn of the Screw

The Governess - Sarah Tynan, Mrs Grose - Heather Shipp, Peter Quint - Nicholas Watts, Miss Jessel - Eleanor Dennis, Miles - Tim Gasiorek, Flora - Jennifer Clark, Conductor - Leo McFall, Director - Alessandro Talevi, Set & Costume Designer - Madeleine Boyd, Lighting Designer - Matthew Haskins, Orchestra of Opera North.

Opera North, Leeds Grand Theatre; Saturday 15th February 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ON%20ToS%20title.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=The Turn of th1e Screw, Opera North at Leeds Grand Theatre product_by=A review by David Truslove product_id=Above: Nicholas Watts as Peter Quint, Sarah Tynan as The Governess and Tim Gasiorek as MilesPhoto credit: Tristram Kenton

February 16, 2020

Luisa Miller at English National Opera

This led not to the political and patriotic work that Verdi wished for but to an essentially domestic drama based on a play by Schiller; the first time Verdi had worked on a purely bourgeois drama. And the longer gestation time allowed Verdi to experiment with ideas learned whilst he was in Paris supervising his opera Jerusalem, so Luisa Miller makes a far greater, and more sophisticated use of the orchestra including two substantial orchestrally accompanied recitatives, and has a new flexibility when it comes to form. We can feel Verdi, almost for the first time, shaping the music to the drama rather than fitting it into pre-existing conventional forms.

The opera, however, is perhaps harder to love than the three operas which came after it, Rigoletto, Il trovatore, La traviata; the characters are all in some way unsympathetic except for Luisa herself. So, it tends to be an opera which is admired and revered rather than loved. Certainly, it has not been seen much on the London stage; there was a rather old-fashioned Filippo Sanjust production at Covent Garden in 1978 which received its final revival in 1981, and then a modish Olivier Tambosi production there in 2003 which was never revived. Apart from that there hasn't been much else beyond valuable concert performances from other opera groups. I was lucky enough to see the work at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in the 1980s with Luciano Pavarotti as Rodolfo, again in a very traditional production. None of these, however, seemed to be able to make a strong case for the piece as drama.

For the new production of Verdi's Luisa Miller at the London Coliseum, English National Opera invited the young Czech director Barbora Horáková, and drew together a strong cast with Elizabeth Llewellyn making a welcome appearance in the UK as Luisa, David Junghoon Kim as Rodolfo, Olafur Sigurdarson as Miller (his ENO debut), James Creswell as Count Walter, Soloman Howard as Wurm, Christine Rice as Federica and Nadine Benjamin as Laura. Sets were by Andrew Lieberman with costumes by Eva-Maria Van Acker, choreography by James Rosental, lighting by Michael Bauer. Alexander Joel conducted. The translation was by Martin Fitzpatrick.

Barbora Horáková was a finalist and prizewinner at the Ring Award Graz in 2017 and received the Best Newcomer Award at the 2018 International Opera Awards. We caught her production of Verdi's early comedyUn giorno di regno at the Heidenheim Festival in 2017. Luisa Miller was a co-production with Oper Wuppertal where it has already been performed, but in an article in the programme book Horáková made it clear that the production had been extensively re-worked (and re-designed) for London (a glance at the Wuppertal production photos in the programme book confirmed this).

The plot is a mixture of family drama and class struggle. Miller (Olafur Sigurdarson) is a retired soldier who expects his young daughter Luisa (Elizabeth Llewellyn) to be a comfort in his old age and is opposed to her being wooed by the mysterious Carlo (David Junghoon Kim). Carlo is in fact Rodolfo, the son of Count Walter (James Creswell), the local lord of the manor. Walter and Rodolfo are at odds, and Walter has a guilty secret, his murder of his cousin enabled Walter to inherit the estate. Central to this is Walter's steward Wurm (Soloman Howard) who lusts after Luisa himself, and a complicating factor is that the young Rodolfo witnessed the murder. Of course, it ends badly.

David Junghoon Kim. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

David Junghoon Kim. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Horáková told the story with clarity, and with no additions and subtractions; she told the story with and through the music (her only alteration was that Wurm did not die at the end). Her chosen language was that of European regie-theater, a style which we do not see regularly in the UK. It is perhaps worth bearing in mind that Horáková's theatrical language would be familiar to many of the opera-goers in Wuppertal. It is also worth bearing in mind a comment by Bernard Haitink. He conducted the Richard Jones production of Wagner's Ring Cycle at Covent Garden; though Haitink famously had doubts about the production, he conducted it because Jones drew such superb performances from the singers and said that it was impossible to dissociate the production from the musical values. So, coming out of this production saying we enjoyed the singing but disliked the production style is doing Horáková a disservice.

Whilst I have no particular enthusiasm for this style of production, I have no objection to it either. As I have said, Horáková told the story with clarity and drew strong performances from her cast as she drilled down into the more complex psychological underpinning of the story. Though it is clear from the interview with her in the programme book that every detail meant something, the visual style of the production was rather too cluttered, what with clowns, balloons, two children representing the more innocent side of Luisa and Rodolfo, dancers who according to Horáková represented the Darkness which was personified by Wurm, the white walls on which people scrawled, the ubiquitous use of a tar-like substance which seemed to get everywhere.

But this emphasis on the psychological paid dividends in the performances which were outstanding, and for the first time I experienced Luisa Miller as riveting drama. It helped that for Acts Two and Three, Horáková allowed us to concentrate on the singers and these two had a far greater sense of focussed drama. We should also bear in mind the negative benefits of Horáková's style, the production lacked the trivialising prettiness of a traditional staging, she stuck to the story and didn't give us her version of Luisa Miller, and there was no over-sexualisation of the plot. Eva-Maria Van Acker's costumes, whilst being of mixed eras and styles (including the chorus in vaguely clown-like Day of the Dead style), gave us a clear distinction of the class layers in this work. Class is important in many 19th century operas, and too many opera directors tend to play this factor down. And those white walls, whilst writing on white walls is a bit of a tired trope I did love the way that black dribbled down them in the second half, giving us a visual metaphor for the way the Darkness encroached. Though the cleaning and laundry bill each night must be huge!

Olafur Sigurdarson, Elizabeth Llewellyn. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Olafur Sigurdarson, Elizabeth Llewellyn. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Technically there are three leading roles (Miller, Luisa, Rodolfo) and three smaller ones (Walter, Wurm, Federica), but the smaller ones received such strong performances here that we had little sense of this hierarchy, instead there was a superb ensemble feel supporting strong individual performances.

Elizabeth Llewellyn was outstanding as Luisa, a young woman who has to grow up quickly and face the real world. She had the flexibility to sing Luisa's often elaborate vocal writing whilst being able to draw out a strong, shapely vocal line. She also conveyed Luisa's psychological journey with great intensity, Llewellyn is a singer who is able to convey much with face and with eyes, this was an intense and gripping experience.

She was well partnered by David Junghoon Kim as Rodolfo. Kim was vivid and tireless in the role, and whilst he did not have the ideal open-throated Italianate sound, he sang with a wonderful intensity whilst giving us a gorgeous mezza-voce for his cavatina at the beginning of Act Three. We never really see Luisa and Rodolfo/Carlo in happier times, but their final long scene as the two lay dying was transcendently magical. The men in the opera are all various types of shit. Whilst Rodolfo happily dupes Luisa, he immediately jumps to conclusions when things go wrong for her.

Her father, by contrast is simply a selfish old git, he pretends to be concerned for her welfare, but he really wants her as a comfort for his old age. Olafur Sigurdarson managed to make the character human, if not entirely sympathetic, and in Act Three when released from prison both he and Llewellyn captured the sense of trauma that the characters have gone through. Sigurdarson's singing was admirably strong and focused, with a great feeling for Verdi's line though there were moments when I worried that he was trying a bit too hard.

Wurm is traditionally portrayed as ugly in some way so that his exterior matches his evil interior, but Soloman Howard's Wurm was anything but. Tall, handsome, physically fit (we got a good view of his upper body muscles) and sexy, Howard was completely mesmerising and disturbing. On stage for a good bit of the time, Howard's presence as Wurm radiated his sense of control and contributed considerably to the character's omnipresence in the plot. Howard sang with a fine, dark line making Wurm as vocally seductive as he was physically, this was an amoral character whom it would be difficult to resist.

Christine Rice. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

Christine Rice. Photo credit: Tristram Kenton.

James Creswell had a different, but equally strong presence as Count Walter; Creswell was the embodiment of entitlement as well as a certain amorality, but also an underlying weakness which was his downfall. Christine Rice was a complete delight as Federica, and we wished Verdi had got his way and made more of the character. Nadine Benjamin, in fine voice, seized her moments as Luisa's friend Laura. Adam Sullivan (a member of the ENO Chorus) gave sterling support as a citizen (in the original, a peasant).

Perhaps more important than individual performances was the terrific feeling of interaction between these, so that the duets and ensembles fair crackled, the dialogue gripped and flowed particularly the scenes between Miller and Luisa, and Luisa and Rodolfo in the last act, creating some fine musical drama.

Andrew Lieberman's sets with their large flat surfaces provided valuable support to the singers, and the expanded ENO Chorus was in terrific form. This was one of the first operas in which Verdi actually made the chorus part of the action; here they are fellow villagers, and the chorus members really seized their opportunities and created a strong dramatic presence.

In the pit, Alexander Joel drew impressive playing from the orchestra, this was an impulsive and dramatic performance. Joel clearly knows and understands Verdi, and this was an account of the opera where the drama and the music were linked, so that moments like Verdi's important long recitative sections were finely fluid, whilst the big moments were thrilling.

By the end of this evening it was impossible not to be gripped by the drama, and to be fully engaged by the music. ENO had put together a strong cast, and Joel and Horáková drew from them some thrilling drama and very fine Verdi singing indeed.

Robert Hugill

Verdi: Luisa Miller

Count Walter - James Creswell, Rodolfo - David Junghoon Kim, Federica - Christine Rice. Wurm - Soloman Howard, Miller - Olafur Sigurdarson, Luisa - Elizabeth Llewellyn, Laura - Nadine Benjamin, A Citizen - Adam Sullivan, Dancers (Stephanie Bentley, Sam Ford, Anna Holmes, John William Watson), Children (William Barber/David Cummings, Halle Cassell/Taziva-Faye Katsande); Director - Barbora Horáková, Conductor - Alexander Joel, Set Designer - Andrew Lieberman, Costume Designer - Eva-Maria Van Acker, Lighting Designer - Michael Bauer, Choreographer - James Rosental, Orchestra and Chorus of English National Opera.

English National Opera, London Coliseum; Saturday 15th February 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Nadine%20Benjamin%2C%20Elizabeth%20Llewellyn%2C%20Soloman%20Howard%2C%20.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Luisa Miller, at English National Opera product_by=A review by Robert Hugill product_id=Above: Nadine Benjamin, Elizabeth Llewellyn and Soloman Howard.Photo credit: Tristram Kenton

Eugène Onéguine in Marseille

The original 1997 production born in Nancy (near Strasbourg) was revived in Nantes (the central Atlantic coast) in 2015 and seen in Saint-Étienne (near Lyon) in 2016, in Nice in 2017 and in Toulon (near Marseille) in 2019 before arriving finally just now in Marseille. All the editions have been staged by the original stage director Alain Garichot though with completely different casts, often Russian, and conductors.

The Opéra de Marseille hit the casting jackpot with a quartet of lesser known French singers (and one ringer — Nicolas Courjal as Gremin) and with young American conductor Robert Tuohy, now music director of the Opéra de Limoges (center southwest of France). The maestro was the ever present, matter of fact purveyor of Tchaikovsky rich panoply of expressive themes, his woodwinds dancing to intensify every movement of poetic beauty flowing through the words of Tchaikovsky’s self made libretto. Mo. Tuohy let Tchaikovsky’s opera be about the words of Pushkin’s troubled lovers, carefully parsing the orchestral phrasing to support these eloquent speakers. And sometimes letting loose with shattering fortes when only the orchestra had something to add.

Emanuela Pascu as Olga, Thomas Bettinger as Lenski

Emanuela Pascu as Olga, Thomas Bettinger as Lenski

And speak they did, each of Pushkin’s characters pouring out their hearts in performances that were not about singers and singing, these were human beings who opened their hearts, intimately, laying bare their raw souls. We sat spellbound, rarely, and reluctantly interrupting the flow of emotion by applauding the famed arias.

Baritone Régis Mengus brought grace and elegance to Pushkin’s bored, existentially “superfluous” hero whose discovery of feeling and change of heart brought an extended, electrifying ending to the evening. In convincing voice he waltzed solo, with consummate skill to his confrontation with Lenski and then coldly shot his best friend in a precisely executed duel. Silently, eloquently he then remained on the stage, lost, during the a vista transformation to Gremin’s ball, months maybe years later.

Tenor Thomas Bettinger sang Lenski impeccably, whose Chopinesque coiffure gave him a poetic presence that made him the poet Pushkin, lest we forget that Pushkin himself was killed in a similar duel. With a spontaneous energy he greeted his intended bride Olga in the first act, then exploded in spontaneous anger in the second act before reflecting on his life, the famed “Kuda, kuda vy udalilis” from an almost detached, closely personal perspective. He then allowed Onegin to kill him — there was only one shot fired.

Soprano Marie-Adeline Henry sang Tatiana, lost within herself, participating quietly, distantly emotional in the wonderful first act quartet of the four women’s voices. She connected with herself in a full, if innocently voiced discovery of her infatuation with Onegin in the Act I Letter Scene. She was then silently, deeply shamed by Onegin’s rebuff. And finally she again connected with her deepest feelings in the final scene with Onegin, this time in a fully lyric dramatic voice, her chagrin turned into electrifyingly personal sacrifice.

Marie-Adeline Henry as Tatiana, Nicolas Courjal as Gremin, Régis Mengus as Onegin

Marie-Adeline Henry as Tatiana, Nicolas Courjal as Gremin, Régis Mengus as Onegin

Bulgarian mezzo soprano Emanuela Pascu is making her career in France though she returns to Bucharest from time to time to sing what must be a beautifully voiced Carmen. Her brilliant first act aria moved effortlessly through the Carmen tessatura with a lightness of spirit that made her Olga a charming, capricious if uncomplicated young woman in love who when called upon could add a powerful, vocally dramatic presence to Tchaikovsky’s masterfully constructed first and second act ensembles.

Bass Nicolas Courjal sang Gremin. Mr. Courjal is a powerful presence (once a Phillip II on the Marseille stage) who made Gremin’s aria a song of his enraptured love for Tatiana, a profound, very alive love he had found later in life. This glowing presence of deep love became the emotional backdrop for the opera’s final scene, the shattering realizations of both Onegin and Tatiana that all love was forever lost.

Gifted with this cast of fine singers of appropriate ages, bodies and spirits stage director Alain Garichot can be credited with evincing these deeply personal, intimate performances of this conceptually unadorned production. Mr. Garichot’s directorial prowess comes out of his many years of formation at Paris’ Comédie Française (an esteemed group of classical actors founded by Moliere in 1680) to teach operatic acting at the young artist program at the Paris Opera and other European opera formation programs.

Mr. Garichot used little else than his singers to realize this emotionally pointed exposition of this operatic masterpiece. He needed no scenery nor did he have much. There were but nine soaring, foliage bare tree trunks on the stage that then disappeared into the loft for the Gremin ball. The only backdrop present was precise detail of character in the masterful enactments of Tatiana’s mother Lariana sung by Doris Lamprecht, Tatiana’s nurse sung by Cécile Galois, the Triquet sung Be Éric Huchet and Lenski’s second sung by Sévag Tachdijian. Of special notice throughout the first act, infusing inescapable actuality, was the mute presence of the nurse Filipievna’s grandson, the messenger of Tatiana’s love.

When it was all over no one dashed for the exits. We all remained seated for extended, solid applause, though there were some whistles (negative) and boos for select singers, and particularly for the conductor. Marseille lived up to its raucous reputation.

Michael Milenski

Production information:

Chorus and Orchestra of the Opéra de Marseille. Conductor: Robert Tuohy, Mise en scène: Alain Garichot; Choreographer: Cookie Chiapalone; Scenery: Elsa Pavanel; Costumes: Claude Massoni; Lighting: Marc Delamézière. Opéra Municipal, Marseille, France, February 13, 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Onegin_Marseille1.png

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Eugene Onegin in Marseille

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Marie-Adeline Henry as Tatiana, Régis Mengus as Onegin

All photos by Christian Dresse courtesy of the Opéra de Marseille

February 12, 2020

Opera Undone: Tosca and La bohème

I don’t think what Opera Undone chose to do with Puccini’s Tosca and La bohème would appeal in the slightest to purists, but on its own terms it was highly imaginative - and not particularly beyond the parameters of some staged productions we might see today at ENO, Salzburg or even Bayreuth.

Where Opera Undone differs is in the concentration of the libretto to an hour in length for each opera, a translation into vernacular English which bears almost no resemblance to the Italian original and in themes which evoke periods in time which are centuries beyond Puccini’s settings. The staging of each opera is so minimalist we could really be anywhere rather than somewhere in particular - it’s almost the Theatre of the Absurd; Ionescu and Beckett, or even Genet, colliding with Puccini. Tosca is probably the less controversial of the two productions here; La bohème is absolutely controversial - and, it should be said, one of the funniest, yet undoubtedly tragic, performances of an opera I have seen.

La bohème , according to Opera Undone, is about polyamory, homosexuality, cruising for picks-ups on gay chatlines, sexual identity, HIV, drug addiction and co-dependency. In one sense I was interested in seeing this production because it was set in Peckham, a part of south London a few miles from the very leafy part of the city in which I live. It would have been easy to stereotype, and, in a sense, this is rather what happened. Marcello (here called Marcus) is every inch the typical Peckham, white, working-class guy - right down to the leather jacket, and silver chains around his neck and wrists. Musetta (Melissa) was even worse. Only Rodolfo (Rod) and Mimi (Lucas) stand outside the stereotypes (though I do know a lot of gay men who wear plaid shirts and jeans). But the subjects touched on are universal, they could have, and do, infect every part of a city. Tosca was simply set in New York; Puccini’s original simply Paris.

La bohème. Photo credit: Ali Wright.

La bohème. Photo credit: Ali Wright.

Condensing either opera down to an hour certainly isn’t easy. Tosca was better done, and we got a fairly good slice of the Scarpia - Tosca scene from Act II here. The focus on both operas was to maintain the big arias - so we got ‘Recondita armonia’, ‘Vissi d’arte’ and ‘E lucevan le stelle’ (or versions thereof), and the same was the case in La bohème. Mimi’s lingering death - whether it be from tuberculosis or from a drug overdose - or whether it is wrought with the power of emotion or with a foaming mouth is long in whichever version one sees it. It is no longer a challenge for an audience to see two men kiss on stage, nor for a libretto to be liberally peppered with “fucks” here and there.

The humour in both productions could perhaps have seemed misplaced, but it worked very well. Cavaradossi (abbreviated to Cav) is still an artist, though should one feel pity for the woman in the audience who spent much of Act I with a picture frame hanging from her shoulders? La bohème was even more striking for involving the audience. Musetta spent an awfully large part of Act I sitting between people or draping herself over them. But strip the humour out and there were moments of drama. Cavaradossi received quite a beating before being hooded and shot; Mimi’s drug induced death was raw, and certainly done with a sense of reflective realism.

The singing was largely very impressive, though the rather intimate size of Studio 2 at Trafalgar Studios can magnify, and sometimes strain, the tone of the voices to a considerable degree. I think all of the soloists deserve credit for bringing in performances that were very well sung - balancing pathos and humour with equitability, and acting, that never bordered on the wooden. Fiona Finsbury’s Tosca was a standout performance, extremely nuanced, and really quite powerful throughout Act II. The notes are there, her upper range entirely confident. She had no difficulty suggesting Tosca’s growing revulsion or despair. The other dominant performance was the Rodolfo of Roberto Barbaro. I think he started slightly short on confidence, but the warmth and colour of his voice is beautiful to listen to. One is entirely persuaded that this is a tenor who emotes what he sings; I could swear that in his duet with Mimi, where Mimi confesses to his drug use after their relationship has ended, there were genuine tears in his eyes.

Tosca. Photo credit: Ali Wright.

Tosca. Photo credit: Ali Wright.

Honey Rouhani’s Musetta was high on humour and high on vocal strength. Roger Paterson’s Cavaradossi provided a couple of moments during his ‘E lucevan le stelle’ where his top notes had both more security at the top and stability in the length of them than I have heard more star name tenors sing. Hugo Herman Wilson’s Scarpia was never short on power, and neither did he shirk from imbuing this particular 1940’s mafia version of him with all his Scarface terror. Michael Georgiou’s Marcelo - he who had voted Tory just once - bounced between Rodolfo and Musetta with witty confidence. Philip Lee’s Mimi ended up becoming a heartrending performance that leant inwards to its inevitable tragedy - the voice clearly capable of going to extremes. His ‘Si, mi chiamano Mimi’ had brought out a very funny side to him as he described selling perfume and taking the late shift at Liberty; and yet, he was entirely moving as he brought an almost positive happiness to his terminal sleepiness after taking one last hit of drugs.

Entirely outstanding throughout the entire evening was David Eaton’s playing of the formidably taxing piano parts of Puccini’s scores.

I’m not sure what my expectations were for this particular evening. Whatever they might have been, purism wasn’t one them. This was in many ways operatic revisionism, opera as theatre, opera as popular art, opera as openly accessible. It could be serious and humorous in equal measure and was an entirely enjoyable way to spend two hours.

Marc Bridle

Opera Undone: David Eaton (Music Director), Adam Spreadbury-Maher (Director)

Tosca : Tosca - Fiona Finsbury, Scarpia - Hugo Herman Wilson, Cavaradossi - Roger Paterson

La bohème : Rodolfo - Roberto Barbaro, Mimì - Philip Lee, Musetta (Melissa) - Honey Rouhani, Marcelo (Marcus) - Michael Georgiou

Trafalgar Studios, London; Tuesday 11th February 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/La%20bohe%CC%80me%20%28c%29%20Ali%20Wright.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Opera Undone at Trafalgar Studios product_by=A review by Marc Bridle product_id=Above: La bohèmePhoto credit: Ali Wright

A refined Acis and Galatea at Cadogan Hall

It was at this estate near Edgware, north-west of London, that the year before Handel had gained employment among the group of musicians that Brydges maintained to perform in his chapel and at private entertainments.

To celebrate their 40th anniversary in 2019, Harry Christophers and The Sixteen released a recording of Acis and Galatea , performed - in accord with what are thought to be the circumstances of the work’s premiere - by an intimate ensemble of just five singers and nine instrumentalists. A year later, The Sixteen have embarked upon a mini-tour of the work, beginning here at Cadogan Hall with further concert performances to follow in Chichester, Derby and Warwick .

The Sixteen’s 2019 disc won the Preis Der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik Best Listen Award; and, at Cadogan Hall, one could understand why. Handel’s beautiful melodies flowed one after the other, sung with mellifluence, elegance and good taste by the five vocal soloists. The nine instrumentalists from the Orchestra of the Sixteen played with similar graciousness of style. The continuo ensemble - cellist Joseph Crouch, theorbo player David Miller, harpist Frances Kelly and harpsichordist Alastair Ross - provided sensitively detailed support. The many instrumental obbligatos conversed engagingly with the voices, Catherine Latham’s sweet piping unheeding of Galatea’s plea to “Hush, ye pretty warbling quire!”; Hannah McLaughlin’s oboe warmly conveying the heat of passion within the eager Acis’ breast; Kelly’s harp embodying the glow of Galatea’s love when reunited with her smitten shepherd.

Arranged symmetrically - the violinists (leader Sarah Sexton and Daniel Edgar) standing stage-right, balanced by the continuo group stage-left - with Christophers dancing lightly on his toes at their centre, the musicians formed a ear-pleasing consort in front of the seated singers at the rear of the stage. So, what could there be not to like?

Well, while the musical performances could not be faulted, I missed the wit, drama and emotion which is present in both John Gay’s libretto and Handel’s score. In Grove, Stanley Sadie speculates: ‘Whether or not it was originally fully staged, given in some kind of stylized semi-dramatic form or simply performed as a concert work is uncertain; local tradition holds that it was given in the open air on the terraces overlooking the garden (the recent discovery of piping to supply an old fountain, suitable for the closing scene, might fancifully be invoked as support).’ And, when Acis and Galatea was presented in a revised three-act version (incorporating musical material from Handel’s cantata Aci, Galatea e Polifemo (Naples, 1708) with words by Nicola Giuvo) at the King’s Theatre in June 1732, the advertisement read, ‘There will be no Action on the Stage, but the Scene will represent, in a Picturesque Manner, a rural Prospect, with Rocks, Groves, Fountains and Grotto’s; amongst which will be disposed a Chorus of Nymphs and Shepherds, Habits, and every other Decoration suited to the Subject’.

At Cadogan Hall, we had neither a ‘rural Prospect’ of Arcadian serenity nor any ‘Action’. The singers undertook, in turn, a decorous progress to the front of the stage to sing their arias, then retreated to resume their positions in the Chorus. It was all very polite and tasteful: ‘courtly’, said one of my colleagues. But, there was little sense of the emotions or psychologies that the work expresses and explores. When Acis and Galatea stood side by side to celebrate their reunion with the joyous, bubbling cries of “Happy we!”, they scarce looked at each other, their apparent indifference surely at odds with their blissful avowals, “Thou all my bliss, thou all my joy!” Similarly, though Polyphemus stood nearby, the audience not the ogre was the recipient of Galatea’s command, “Go, monster, bid some other guest/ I loathe the host, I loathe the feast”? And, because the monstrous one did indeed beat a retreat, Coridon’s implorations to his master to “Softly, gently, kindly treat her” were sung to no-one in particular.