June 30, 2020

Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies (Vol.2) - in conversation with Adrian Bradbury

So wrote the music critic of the Morning Post following a performance by the Italian cellist, Carlo Alfredo Piatti, on 12 th July 1844, as part of the third of that year’s three matinée concerts at the Hanover Square Rooms organised by the pianist Theodor Döhler (and recalled by Morton Latham in his 1901 monograph Alfredo Piatti - A Sketch).

Piatti’s Operatic Fantasy on three numbers from Bellini’s penultimate opera remained unpublished during his lifetime. It is one of three such fantasias based upon themes by Bellini (La sonnambula and I puritani being the other two operas) that cellist Adrian Bradbury and pianist Oliver Davies include on the first volume of Piatti’s Operatic Fantasies which was released on the Meridian label last year, and which has now been followed by this second volume, thereby completing the set of twelve.

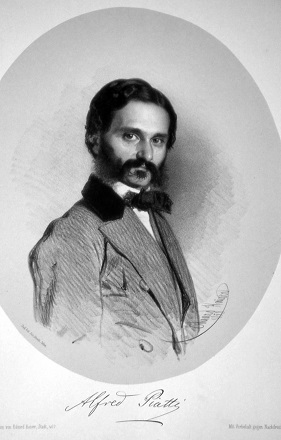

Born in Bergamo in 1822, Alfredo Piatti became one of the most renowned cellists of the 19th century. His father was a violinist but the 5-year-old Piatti began learning the cello, under the tutelage of his great-uncle, Zanetti, a music teacher and cellist of considerable accomplishment. By the age of seven he was playing in the local opera orchestra, and subsequently enrolled at the Milan Conservatoire where he received lessons from Vincenzo Merighi until September 1837. A successful performance at the Teatro della Scala in 1838 furnished him with sufficient funds to undertake a European concert tour, earning acclaim in cities such as Venice and Vienna.

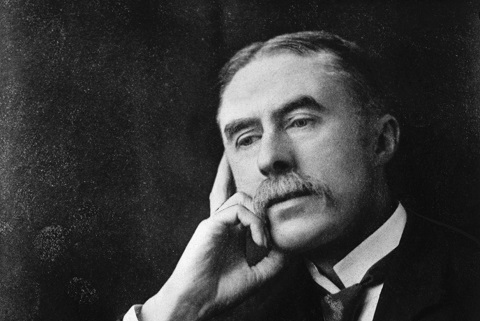

Alfredo Piatti (Lithograph by Eduard Kaiser, 1858)

Alfredo Piatti (Lithograph by Eduard Kaiser, 1858)

1843 found Piatti in Munich. He met Liszt who invited the cellist to share a concert billing in Paris, gifting him an Amati cello upon learning that financial pressures had forced Piatti to sell his cello and perform on borrowed instruments. (Piatti later own the ‘Piatti’ Stradivarius.) He travelled widely - to Berlin, Breslaw, Dresden, Paris and St Petersburg - arriving in London in 1844, where the cellist who had spent his boyhood playing in the opera orchestras of Bergamo, accompanying the finest bel canto singers of the day, eventually becoming principal cello in Royal Italian Opera at Covent Garden.

In London he became a distinguished and celebrated artist and teacher. (As Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielweski explains in The Violoncello and its History, as Professor of Cello at the Royal Academy of Music, Piatti taught many of the day’s finest cellists, Hugo Becker, Robert Hausmann, William Edward Whitehouse, William Henry Squire, Leo Stern and Edward Howell among them.) He became friends with Mendelssohn, who wrote a concerto for him, as did Arthur Sullivan; he gave the British premiere of Schumann’s Cello Concerto.

Piatti’s first private performance in London took place at the house of one Dr Billing, then the medical adviser at the Opera, alongside the Italian singers soprano Giulia Grisi and tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini. The London public first enjoyed his playing on 31st May at the Annual Grand Morning Concert given by Mrs Lucy Anderson, pianist to Queen Victoria, the Morning Post reporting: ‘Signor Piatti, a violoncello performer from Milan, made a most successful debut. He played a fantasia on themes from Lucia ... His style resembles that of Servais; and a clear and liquid tone, with great equality all over the board, struck amateurs as being particularly fine … his certainty and precision were unerring.’

Invited by Döhler to play at the first of the Hanover Square Rooms matinées that year, Piatti gave a solo performance that prompted the critic of the Musical World to eulogise, ‘M. Piatti performed a violoncello fantasia in which he displayed as great a command of this instrument as we ever recollect to have heard’, and the Athenaeum reviewer to observe that Piatti had ‘obviously formed his cantabile playing on that of the singers of his own country’ - an astute comment, given that many subsequent accounts of his playing noted that his cantabile playing offered valuable lessons to vocalists.

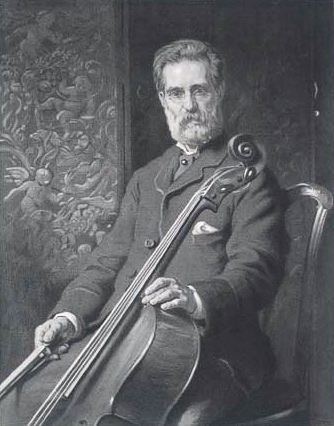

Alfredo Piatti (Frank Holl, 1871)

Alfredo Piatti (Frank Holl, 1871)

A month after his first public London debut, Piatti made his first appearance at a concert of the Philharmonic Society, on 24th June, following Mendelssohn’s performance of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto with a Cello Fantasia by Friedrich August Kummer. A great raconteur, later in his life Piatti recalled that this was the only time that he heard an English audience call out ‘Bravo’ when he was mid-phrase! The Morning Post praised his ‘magnificent violoncello playing [which] won universal admiration … the perfection of his tone and his evident command over all the intricacies of the instrument’, while the Times judged him ‘a masterly player on the violoncello. In tone, which foreign artists generally want, he is equal to [English cellist Robert] Lindley in his best days; his execution is rapid, diversified and certain, and a false note never by any chance is to be heard.’

Piatti was one of the last cellists to play in the ‘old’ style, without an endpin. A fine composer he enriched his instrument’s repertoire with two concertos, a concertino, a Fantasia romantica and a Sérénade Italienne. He is best known today for his technically demanding 12 Caprices Op.25, though he wrote sonatas, songs (some with cello obbligato), themes and variations and other small works, and produced important editions of 18th-century cello works by Locatelli, Boccherini and Bach.

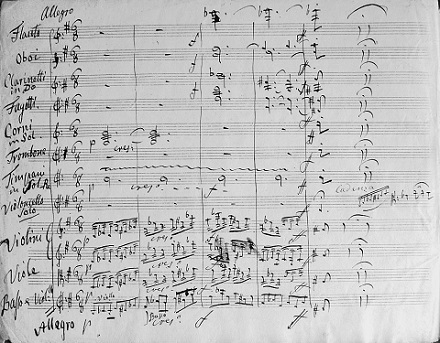

However, it was his fantasy compositions on operatic themes with which Piatti launched his career and which so dazzled the salons and concert halls of Europe, and it is these 12 Fantasias, many unknown and unheard since performed by Piatti himself, that Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies have ‘exhumed’ from the Piatti archives at the Biblioteca Musicale Gaetano Donizetti in Bergamo, edited, performed, and now recorded in this two-volume set.

Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies recording ©️ Richard Hughes

Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies recording ©️ Richard Hughes

In conversation, I ask Adrian how this intriguing project had come about. As a boy he had loved Piatti’s music, he explains - all young cellists know and play the Caprices! - and when he was asked to perform at the Royal Academy of Music’s 2011 celebration of their 100-year long residence at their custom-built premises in Marylebone Road, whose music could be more apt than that of Piatti, who for 25 years had been the Academy’s Professor of Cello? Adrian recalls, as a child, hearing his father, clarinettist Colin Bradbury, preparing for recordings of 19th-century repertory with the pianist Oliver Davies, and having explored reviews of Piatti’s playing, he asked Oliver to prepare a score of the unpublished Fantasia on themes from Bellini’s Beatrice di Tenda, the autograph manuscript of which was photographed and supplied by Dr Annalisa Barzanò, co-author of Signor Piatti - Cellist, Composer, Avant-gardist (2001), and musicologist at the Library G. Donizetti in Bergamo. Oliver studied the cello solo, piano score and orchestral parts, and - taking into account the evidence that they provided of Piatti’s revisions - was able to piece together the jigsaw with considerable certainty. Alongside the Beatrice di Tenda Fantasia, at the RAM Adrian and Oliver also performed the Fantasia on Bellini’s La sonnambula, one of the few of the 12 that has been published. Enthusiastically received, the Fantasias “really lived” through their songs, Adrian suggests.

Listening to Adrian and Oliver perform ‘Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda’ (Volume One), I am struck by the way Piatti fuses lyricism and drama, creating a sense that the melodic material is evolving organically and inevitably. And, I’m sure the Morning Post critic would be just as impressed by Adrian’s ability to sing with equal persuasiveness through the extensive melodic phrases, the energetic excursions to the cello’s stratosphere and depths, and the delicate intricacies and ornaments, as he was when he applauded Piatti’s ‘vanquishing’ of seemingly ‘insuperable’ difficulties - I certainly heard pitches at a frequency that I don’t think I’ve heard from a cello before, and beautifully sweet they were too! Moreover, there’s a lovely spontaneity about Oliver’s and Adrian’s playing which seems to conjure the excitement of the opera house and live performance. It’s impossible not smile during the capricious episodes, or to be repeatedly impressed at how such lighter moods segue with deceptive ease into sweet sorrow, or troubled turmoil. Oliver’s interjections are perceptive and sensitive, as if instruments in the pit were being coaxed in their turn to emerge from supportive accompaniments and join the singer in melody.

Autograph manuscript of Parafrasi sulk barcarola del Marino Faliero by Alfredo Piatti ©️Annalisa Barzanò

Autograph manuscript of Parafrasi sulk barcarola del Marino Faliero by Alfredo Piatti ©️Annalisa Barzanò

During the following decade, the duo set about preparing all twelve Fantasias, and performing them regularly. Every few days, an email to Annalisa would prompt the swift arrival of the next set of high-resolution photographs in Adrian’s in-box. When he apologised for ‘bothering’ her so regularly, Annalisa explained she had written her book primarily so that Piatti’s music might be heard again. He will “never forget the buzz I felt the first time that I downloaded the manuscript from my drop-box, printed it and placed it on the music stand”. Oliver’s experience and knowledge of the bel canto repertory enabled him to quickly identify the arias upon which Piatti had drawn and as the prepared Fantasies grew in number, then Artist By-Fellows at Churchill College, Cambridge, they gave performances at the College.

Adrian and Oliver present the ‘Introduction et Variations sur un thème de Lucia di Lammermoor’ which so impressed the Morning Post reporter, in the second volume of Operatic Fantasies. This disc includes three other Fantasias on operas by Donizetti, who had become a friend of Piatti’s father, Antonio, whilst they were both studying with Simon Mayr in Bergamo. Piatti, who had himself played in the Bergamo premiere of the opera in 1838, selected the climactic closing aria, ‘Tu che a Dio spiegasti’, as his starting point, preceding his fantasy on Edgardo’s grief-stricken plea that he might join the dead Lucia in heaven, with an Andante Lento of his own.

The piano’s dark, tense opening resonates with the horrors and histories of the cemetery in with Edgardo sings his lament, and Adrian captures both the vulnerability and despair, tapering Piatti’s drooping phrases beautifully, and the sudden, brief surges of pain and passion during which it seems as if Edgardo’s heart will burst with anguish. Plunges and peaks, supported by rumbling, oscillating octaves, sudden transmute from turbulence to tenderness, as the cello theme voices Edgardo’s transfiguring memories of Lucia’s purity and virtue. Adrian and Oliver persuasively guide the listener through the unfolding variations with an effortless lyricism and technical assurance: the cello’s double-stopped octaves and racing scales of thirds are pinpoint-true, harmonics ring brightly and whisper softly, the athletic demands are understated - but no less impressive - and the melodising unwavering.

Adrian Bradbury ©️ Richard Hughes

Adrian Bradbury ©️ Richard Hughes

Why had this music languished unheard for so long? Adrian reflects upon the reluctance of Piatti’s contemporaries to perform his music during his lifetime: perhaps they were in awe of his virtuosity and wished to avoid direct comparison? We discuss the subsequent waning of the popularity of the fantasia form, and of the bel canto style itself. Perhaps the Fantasies were just too closely associated with Piatti himself? Adrian draws attention to one Francesco Berger (1834-1933), a celebrated Professor of Piano at the RAM who invited many Italian refugees to perform at his home, noting that ‘it was the fashion then for performances of popular airs - an introduction, air and variation … how strange now.’

Why were Piatti’s Fantasies so popular, I wonder? “It’s the opera in them,” suggests Adrian, “one cannot separate bel canto from Piatti”. The Fantasies “sparkle”, but they are notable not just for their virtuosity: their musicianship is supreme. “All his life Piatti played this repertory. He performed with Verdi’s wife, Giuseppina Strepponi, he shared a stage with the finest singers of his day - Giuditta Pasta, Grisi, Rubini, Luigi Lablache, Antonio Tamburini, Jenny Lind, Maria Malibran and Michael Balfe. He wrote from the heart, but the ‘style’ is correct: the Fantasias are a delight, but Piatti was not simply ‘dabbling’. They are not a vehicle for virtuosity but, like the Caprices, works of real quality. The virtuosity was taken for granted, it was the musicianship that Piatti put first.” Whereas others cobbled together works which would showcase their skill and dexterity, Piatti took composition seriously and continued studying to the end of his life.

Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies performing in Sala Piatti, Bergamo

Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies performing in Sala Piatti, Bergamo

One can hear just what Adrian means when listening to the only Fantasy in these two volumes which is not based upon the music of one of Piatti’s bel canto contemporaries - the ‘Impromptu on an air by Purcell in the Indian Queen’. Piatti wonderfully captures the musical spirit of the English composer, the precise rhythmic emphases that lend such a distinctive quality to Purcell’s songs and airs, the smoothly evolving melodies which Purcell - who might be described as the ‘creator’ of English secular melody - modelled on the Italian style of expressive singing that he studied and admired. But, Piatti integrates Italianate delicacies and graces, the cello interrupting the piano’s simple first phrase with some elaborate flourishes then tenderly duetting with the theme, first joining as one voice, then stroking the line with curls, trills, flights. And, just when it seems that the ground is shifting towards the Italian style, so Piatti shows one to have been deceived. This is not just an example of Piatti’s compositional skill but also of his remarkable ability to assimilate varied material. Adrian’s and Oliver’s performance of Piatti’s stylistic sleights of hand is utterly magical.

Adrian explains that Piatti’s personal experience is integral to these works. The bel canto conductor Jeremy Silver advised Adrian that the Fantasias are fascinating from a conductor’s perspective. “You can see it, for example, in the articulation that Piatti marked in the Lucia part: he uses a special articulation mark - a wavy line - a cantabile indication which he placed over all the operatic phrases. It is to be played ‘legato, almost separate’. It’s as if Piatti is imagining the singers on stage beside him.” The decorative fioritura, the declamation of the recitatives, cadenzas, cadences and ornaments: all are meticulously indicated. “Piatti inhabits a bel canto ‘skin’ in order to communicate the essence of the music.” Similarly, the fingering and portamenti are finely marked. “Even in the Fantasias that were not published [six were published by Ricordi and Schott]. Though he alone played them, we are sure Piatti was always aiming for future publication.”

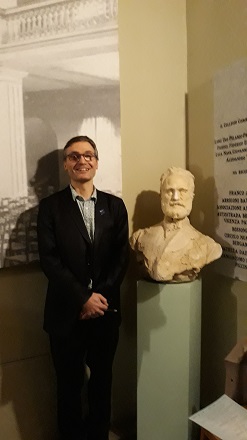

Adrian Bradbury next to bust of Alfredo Piatti, Sala Piatti, Bergamo

Adrian Bradbury next to bust of Alfredo Piatti, Sala Piatti, Bergamo

The bel canto spirit infuses every aspect of these Fantasias, Adrian believes. He found himself listening to and learning from the singing of Joan Sutherland, with regard to how to interpret the ornamentation. “The cello bow becomes the diaphragm; the double-stopping becomes duetting. It must feel as if you are singing; if not, you are in trouble,” he laughs. When the Royal Opera House presented Bellini’s La sonnambula in 2011, Oliver urged Adrian to see the production. Admitting that he had not seen the opera before, Adrian tells me of the tremendous impact that the solo arias, particularly the declamation, had upon him. Hearing the familiar melodies, it was as if he was experiencing them entirely anew, learning again and putting the tunes in context. “String players must listen to singers, and bel canto singers most of all, to learn to play cantabile.”

Adrian hopes that these recordings will lead to the Fantasias becoming valuable and wonderful additions to the repertoire. “And we can’t wait to be allowed to return to Bergamo - so devastated by Covid-19 - to hug the Piatti scholars once more for sharing their manuscripts and to present more of the Fantasias in the wonderful Sala Piatti, with the Frank Holl portrait of Alfredo Piatti looking down at us - approvingly I pray!- from the side of the concert hall.”

Claire Seymour

Adrian Bradbury (cello), Oliver Davies (piano)

Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies

Volume One: Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda*; Souvenir de La sonnambula, Op.5*; Souvenir des Puritani, Op.9*; Capriccio sopra un tema della Niobe, Op.22; Fantasia sopra alcuni motivi della Gemma di Vergy; Impromptu on an air by Purcell in the Indian Queen*

Volume Two: Introduction et Variations sur un thème de Lucia di Lammermoor, Op.2; Rondò sulla Favorita*; Souvenir de l’opéra Linda di Chamounix, Op.13; Parafrasi sulla Barcarola del Marino Faliero* Rimembranze del Trovatore, Op.21; Capriccio sur des Airs de Balfe*

*world premiere recording

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Operatic%20Fantasies%20Vol.2%20Meridian.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies” (Volume 2) product_by=Adrian Bradbury (cello), Oliver Davies (piano) product_id=Meridian CDE 84659 price=£12.00 product_url=https://www.meridian-records.co.uk/acatalog/CDE84659-Piatti.html#aCDE84659June 29, 2020

Live from London: first-ever global online vocal festival announced

The festival will be broadcast every Saturday for ten weeks from the 1st August 2020. It has been designed to raise money for artists, venues and promoters to cover their COVID-19 losses, and to reunite the world's many singers, and audiences with much needed live concerts.

Broadcast in HD from the beautiful VOCES8 Centre (St Anne and St Agnes Church), in the heart of the City of London, viewers will be able to pay for exclusive access to season or individual concert tickets. Award-winning artists featured include VOCES8, I Fagiolini, Stile Antico, The Swingles, The Sixteen (from Kings Place), The Gesualdo Six, Apollo5, Chanticleer (from San Francisco) and a special guest appearance by The Academy of Ancient Music. The ensembles will be performing their favourite works, and pieces for which they've become renowned, singing repertoire from the Renaissance to contemporary A Cappella.

The festival is a heart-warming display of vocal ensembles helping each other in a time of crisis. These concerts will be some of the first performances by the ensembles since the start of the lock-down restrictions at the beginning of the year. A portion of all ticket sales will be put towards funding for grassroots music education, and to addressing topics of diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility in choral music.

Season passes are £80 (£8 per concert, per household). Single concert tickets will be available for £12.50. Concessions have been crafted for students and choirs across the world, as well as special deals for promoters and venues. Artists will share income from season ticket sales, as well as individual concert income. This approach goes beyond free streaming on social media, allowing a revenue channel for promoters, venues and artists (most of whom are freelance).

Taking the lead from current sporting events, the concerts will be broadcast from a closed venue. Singers and crew will be following the strict government guidelines about safety and distancing in the workplace.

The VOCES8 team continues to lead the charge in its forward-thinking, inclusive initiatives in the choral sector. Live from London follows the online work the VOCES8 Foundation has been doing over lock-down with its #liveathome series - more than 100 broadcasts of online performances, participation events and interactive sessions. Its reach highlighting the hunger for vocal music around the world VOCES8’s 15th Anniversary is celebrated by the release of their new album After Silence on the 24th July.

https://voces8.foundation/June 28, 2020

'In my end is my beginning': Mark Padmore and Mitsuko Uchida perform Winterreise at Wigmore Hall

For, this series of 20 lunchtime recitals, live streamed via the Wigmore Hall website and broadcast on BBC Radio 3, has been very much more than a ‘good thing’: the performances have not ‘just’ been an opportunity to enjoy remarkable music and musicianship, technical mastery and expressive commitment, but also astonishingly, though not surprisingly, fulfilling and uplifting, and perhaps ground-breaking too.

And, as Artistic Director, John Gilhooly, reassures us, although Wigmore Hall will fall silent for a few months - to allow a clearer picture to emerge as to how long this crisis will continue for live performance, and for musicians, and decisions about the autumn and winter programmes can be taken - the doors of Wigmore Hall will re-open and welcome audiences back for live performances.

This recital by tenor Mark Padmore and pianist Mitsuko Uchida was, though, the final concert in this wonderful series, so it was ‘an end’ of sorts. Schubert’s Winterreise is also a journey towards an ‘end’ - rest, death, the abyss, perhaps renewal. Initially, though any opportunity to hear these two musicians perform Schubert’s song-cycle is always to be grasped, I wondered if the programming was not a little too bleak: hope rather despair, resurrection rather than oblivion, is what we long for and need. Moreover, listening at mid-day at the peak of a mini midsummer heatwave didn’t seem the most helpful circumstances in which to empathise with the chilling introspection of the traveller’s winter journey across the icy landscape, into his own psyche and beyond into nothingness.

But, I need not have feared. The soft and surreptitious tread of the piano at the start of ‘Gute Nacht’ - Uchida somehow managed to convey the slightest of propulsive swellings through the first two bars of piano breathing - was both an ending and a beginning: a gentle farewell to the present and the commencement of a journey through an emotional terrain, ever more extreme. That’s not to suggest that there was anything overly mannered about Padmore’s and Uchida’s approach. Quite the opposite. And, it was that very clarity and directness, judgement and sensitivity, that made their performance so powerful, almost overwhelmingly so, given the context. The empty seats in the Hall, the wanderer’s isolation and alienation, the cycle’s movement towards an existential void: the nothingness accrued with terrible inevitability, a terrifying echo of the cultural vacuum that occasionally casts an grim shadow on the nation’s horizon, despite Gilhooly’s confidence that the arts, which “are central to the international standing, character and wellbeing of the nation” will, play “a huge role in our national recovery”.

Padmore and Uchida brought every quality of their musicianship that we know and love, to bear upon this music. Padmore’s tenor, ever sweet, with an occasional slightness or strain at the top poignantly emphasising the protagonist’s physical and mental struggle, enunciated and inflected Wilhelm Müller’s poems with meticulous precision and perceptiveness. Uchida’s playing was thoughtful and unrushed, the elegant clarity of her playing enabling her to paint crystalline images and imagery.

There was so much to admire and which intrigued, so much detail which compelled, and so many aspects of this performance that were deeply moving, that it is almost impossible to know where to begin, or what to select, and what to omit. There was Padmore’s beautiful legato and tapered phrasing in ‘Gute Nacht’, and the sudden forcefulness and anger at the start of the third stanza which then diminished into the lingering softness of the final major-key stanza which acquired a patina of even deeper sadness from such contrast; and, a similarly dramatic and restless contrast of floating leise and assertive laute in ‘Die Wetterfahne’, and the leanness of Uchida’s textures - the snatching away of the final trill felt cruel and hard. Fire and ice were similarly, via a wonderfully expressive rubato, counterposed in ‘Gefrorne Tränen’, but always the momentum was onwards, unstoppable, frightening.

‘Erstarrung’ swirled with a torment born on the wind and through the soul: I think I held my breath from start to finish. With ‘Die Lindenbaum’ we entered a consoling vision, the fragile unreality of which was pointed by Uchida’s soft steel-edged interjections, and which was swept aside with terrifying brusqueness by the blast which blows the hat from the wanderer’s head, leaving just a tantalising, teasing dream of what might have been. I don’t think I’ve ever heard such a unity of longing and frustration, pain and fury, flood through the final phrase of ‘Wasserflut’: “Da ist meiner Leibsten Haus.” Similarly, Uchida’s wonderfully/terribly dry staccato in ‘Auf dem Flusse’ made the musical imagery of the swelling under the crust of ice that coats the river - as the voice releases its fears, supported by the rich piano bass, now released from its fetters - almost impossible to bear.

With ‘Irrlicht’ - snatched fragments, poignant octaves, richer indulgences - the disintegration of the protagonist’s wholeness seemed to begin. Have the cocks and ravens that disrupt the dreams of spring ever felt more devilish? Or the whispered, silken retreat to a fantasy of love’s renewal more beguilingly dangerous? The daring temporal freedom in ‘Einsamkeit’ pressed home the self-destructive emotional excess which the wanderer bears; in ‘Der greise Kopf’, wisdom and wistfulness only just repressed upswells of painful emotion, and the darkness lingered in the uncomfortable shadows of the low-lying ‘Die Krähe’.

Padmore did, entirely forgivably, tire a little, and some of the latter songs were a touch less ‘accurate’, but this often lent them a vulnerability that was deeply affecting: in the face of the crisp rattles and barks of ‘Im Dorfe’, the protagonist’s dismissal of the dogs’ warning, and of the invitation to dream, seemed all the more dangerous. What did not ever lessen was Padmore’s acuity with regard to verbal weight and meaning: there was a heart-wrenching moment of self-awareness in ‘Täuschung’ when the wanderer recognises and condemns his own susceptibility to dreams and hope - this seemed to propel us into the abyss. ‘Das Wirthaus’ is marked sehr langsam and Uchida played the piano introduction as if she could not take a single step further - I could feel the suffocating weight on my own shoulders - and then through the burden floated the blanched but ever sweet vocal line, condemning the signs that invite travellers into cool inn.

In ‘Mut’, Padmore seemed to push forward more than Uchida expected, and now it was the pianist who seemed a little weary, though this only added to the verisimilitude. I shut my eyes during ‘Die Nebensonnen’, always the most wonderful moment of transfiguration. And, then, only the hurdy-gurdy man stood between us and nothingness. Has the imagery of ‘Der Leiermann’ every seemed more apt or painful? - “with numb fingers he grinds away as best he can”, “barefoot on the ice … his little plate remains always empty”, “No-one wants to hear him, no-one looks at him … the dogs growl”.

For the first time in this series, the silence after the music had dissolved into the void was truly appropriate and profound. But, the end of ‘Der Leiermann’ seems to beckon us into a journey of renewal, “Shall I go with you? … Will you, to my songs, play your hurdy-gurdy?” asks the exhausted wanderer. Are we propelled back to the opening of ‘Gute Nacht’, in media res? Perhaps the piano’s relentless steps have never stopped - so out of the void will come music? The hurdy-gurdy man’s abyss may at first seem an alarming metaphor for the imminent silencing of the nation’s cultural life, but perhaps his music is infinite?

Padmore himself, in his opening remarks, reminded us of Brecht’s motto to his Svendborg Poems (1939):

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing

About the dark times.

And in an essay, ‘Undefeated Despair’, written in 2006 in response to the growing crisis in Palestine, John Berger wrote of ‘Despair without fear, without resignation, without a sense of defeat.’ As the lights go out at Wigmore Hall for an unknowable length of time, let us hope, and be certain, that the bright times, and the singing about them, will return to our lives soon.

Claire Seymour

Mark Padmore (tenor), Mitsuko Uchida (piano)

Franz Schubert - Winterreise D911

Wigmore Hall, London; Friday 26th June 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Uchida%20and%20Padmore.bmp image_description= product=yes product_title=Winterreise, Mark Padmore (tenor), Mitsuko Uchida (piano) - Wigmore Hall, London product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Mitsuko Uchida and Mark PadmorePhoto courtesy of Wigmore Hall

June 27, 2020

Those Blue Remembered Hills: Roderick Williams sings Gurney and Howells

Whether singing to the birds of the Warwickshire countryside from his rural garden, participating in Wigmore Hall’s ground-breaking live lunchtime recital series, or popping up as Papageno - reliving memories of his 2017 Covent Garden performances by self-accompanying ‘Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen’ with a percussion orchestra of ‘tuned’ glasses and forks - Williams doesn’t seem to have had a ‘quiet’ lockdown in any sense of the word.

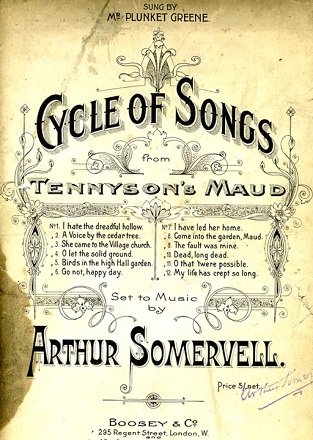

Another thing that seems to have been ringing regularly in my ears of late is music from what is often termed the ‘English Musical Renaissance’, those late Victorian and Edwardian years when English composers sought, by drawing on folksong and music from the Tudor and Stuart period, to establish a contemporary national musical idiom, distinct from but equal to European traditions and styles. Williams has been a strong presence in this regard too: alongside performances of Butterworth and Vaughan Williams, Williams’ and pianist Susie Allan’s interpretations of Sir Arthur Sullivan’s song-cycles A Shropshire Lad and Maud was released by Somm Recordings in May, and now we have the opportunity to hear Williams return to Housman as set by Ivor Gurney, alongside the music of Herbert Howells, on this splendid Em Records release, Those Blue Remembered Hills.

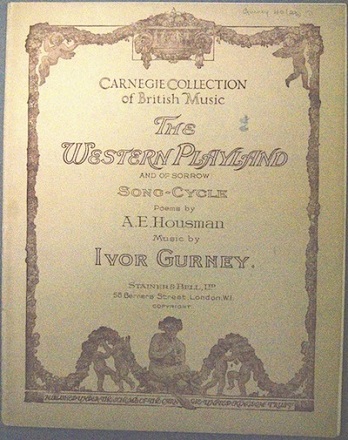

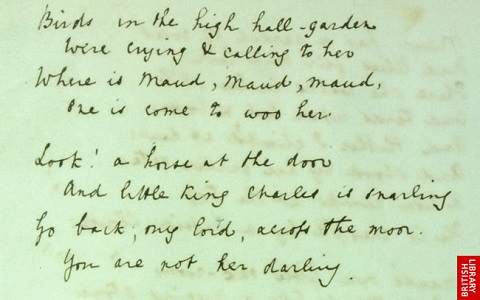

The works presented on Those Blue Remembered Hills were all composed between 1914 and 1925, and several are world premiere recordings. This disc opens with Gurney’s The Western Playland (and of Sorrow), a song-cycle comprising eight settings of poems from Housman’s A Shropshire Lad, in which Williams is joined by pianist Michael Dussek and the Bridge String Quartet. These instrumentalists also performed, with tenor Charles Daniels, on an earlier Em Records disc, Heracleitus, which offered another Gurney setting of Housman, Ludlow and Teme, composed in the same year. At the Royal College of Music, Gurney had studied both German lieder and French mélodie traditions, but both of these Housman song-cycles are evidently influenced by Vaughan Williams’ On Wenlock Edge (1909) which Gurney heard in 1919. They were published as part of the Carnegie Collection of British Music, Ludlow and Teme in 1923 and The Western Playland in 1926.

Gurney had revised both scores while he was a patient at the City of London Mental Hospital in Dartford, Kent, where he remained until his death in 1937 at the age of 47. The cycle is presented here in a new edition by Philip Lancaster, who explains (in one of several of the liner book’s illuminating articles, and elsewhere) that Gurney’s revisions were quite substantial - ‘textures were added and reworked, the scoring often wholly altered (one song originally scored largely for strings was in revision accompanied largely by piano); harmonies became more diffuse, in Gurney’s impressionistic vein; and the songs in parts substantially redrafted’ - and sometimes very problematic (in one case, leading Lancaster to return largely to the original 1920 version). Reflecting on the title, Lancaster speculates that title of The Western Playland alludes to both the Western Front and to Gurney’s home county of Gloucestershire, while ‘and of Sorrow’ which was added in 1925 may be inspired by A Shropshire Lad poem, not set here:

‘In my own shire, if I was sad,

Homely comforters I had:

The earth, because my heart mas sore,

Sorrowed for the son she bore;

And standing hills, long to remain,

Shared their short-lived comrade’s pain.’ (XLI)

As one would expect, Gurney’s musical responses to Housman’s poems are sensitive and intensely lyrical. Listening to the cycle for the first time, I heard a Brahmsian touch in the melodies, but I was struck by the flexibility of Gurney’s forms and melodies as he shapes each song and phrase precisely to the sounds and sense of the poetic text, and by the surprisingly unpredictable harmonic twists and heightenings. The instrumental accompaniments are no less diverse in timbres, texture and colour, and they serve as sonic landscapes which support the verbal meaning and emotion. The songs present considerable technical challenges for all the performers. The instrumentalists must balance ever-changing textures, while the singer must negotiate sometimes angular melodies which rove through restless rhythmic shapes and wide-ranging tessituras. The smooth legato that Williams sustains, seemingly effortlessly and always articulating the texts with precision and finely judged emphasis, is notable.

Roderick Williams

Roderick Williams

‘Reveille’ is a stirring dawn cry, the first three stanzas opening with exhortations to “Wake”, “Wake”, “Up, lad, up, ’tis late for lying”: time passes, each moment must be lived to the fullest. But, ‘reveille’ does not just infer sunrise, it is also the word used to describe the bugle-call that wakes the military, and we hear the beat of soldiers’ drums in the firm stamp of the piano bass and cello. Williams brilliantly unites lyrical vocalism with declamatory briskness, and echoes between instruments and the voice conjure energy. Though the central section is more dreamy, with thoughts of lands untrod and beckoning hovering softly in the upper strings, up and onwards it must be. Yet, the quietude of the postlude and the poignancy of the viola’s ‘last word’ remind us, “There’s be time enough to sleep” - as Gurney himself confirmed in his own eloquent song to that ‘eternal rest’.

The theme of transience is developed in ‘Loveliest of Trees’ in which the seventh-based harmony of the opening and impressionistic progressions create a fleeting, vulnerable quality. There is such delicate melancholy in the falling motif - a blossom floating gently to the ground - which opens the piano introduction and vocal line, and which the strings, generally restrained throughout, develop in the eloquent postlude. This is the sort of song, and singing, which warms the heart even as it brings hot tears to one’s eyes. Indeed, “With rue my heart is laden” sings the poet-speaker after the strings’ tender introduction to the more folk-like ‘Golden Friends’. Williams’ often unaccompanied vocal line is wonderfully light and even, threatening at times, it seems, to disappear but softly sustaining its recollections of “lightfoot boys” and “rose-lipt girls … sleeping in fields where roses fade”, until a whispered postlude unfurls sweetly into silence.

Gurney was a keen sportsman as a schoolboy, and football and cricket momentarily keep grief at bay, sustaining a lust for life in the brief ‘Twice a Week’. Williams’ baritone may be strong and resolute but the singer’s sentiments are belied by the brusqueness of the gruff, dissonant strings and the rhythmic instability of the song (which Williams negotiates with pinpoint accuracy), especially in the final stanza where the thundering syncopation in the piano bass, mis-accented text-setting and dense string discords seem to disdainfully sneer. ‘The Aspens’ is folk-like rumination on eternal nature’s indifference to man’s transience, seen through the eyes of a widower who predeceases his second wife, thereby perpetuating the cycle of love and loss. Williams’ unaccompanied vocal entries are sweet and sure, and the long phrases - the time-signature ceaselessly changing - extend with lyrical eloquence, accompanied alternately by strings and piano, the instruments coming together when the voice is silent. Each time the singer notes the watching aspen, the vocal line rises to a peak and then falls an octave interval, and the smooth evenness with which Williams’ shapes this expressive gesture is deeply moving.

Michael Dussek.

Michael Dussek.

Gurney eschews the invitation in ‘Is my team ploughing’ to vocally distinguish the ballad’s speakers preferring instead to oppose the text and accompaniment to underline the song’s poignancy. For example, the questions from the man who lies in the earth, “Is my team ploughing”, “Is football playing … Now that I stand up no more?” are answered by the relentless jigging, jangling quavers in the piano and strings which cruelly tease with their undeniable presence and vigour. Tension builds as the harmonies and textures complicate, but “Is my girl happy” interrupts: a pianissimo dynamic, a descending vocal phrase and the commencement of an ominous syncopated low octave pedal in cello and piano bass lead to a solo parlando question, sung with quiet but heart-wrenching directness by Williams, “And has she tired of weeping/ As she lies down at eve?” The strings’ hushed answer ‘replies’ powerfully and plaintively. This is a tremendous unity of lyricism and drama.

However, The Western Playground ends in more joyful fashion, with ‘March’, a setting of the longest poem of the eight, ‘The sun at noon to higher air’. The piano’s light arpeggio triplets, symmetrically patterned, and the strings’ concordant sweetness conjure youthfulness and optimism, while the constant lilt of two-against-three creates a naturalism and freedom that is perfectly embodied by the relaxed warmth of Williams’ baritone. There are pauses for instrumental reflection between the stanzas, and a more ambiguous mood marks the fourth stanza’s mirage-like, symbolist vision of farm girls resting in the palms’ shadows beside the pond’s and hedge’s “waving silver-tufted” wands. But, with the firm assertion that “lovers should be loved again”, Gurney closes not with loss and longing but with life and love. The lingering postlude at first seems to question such certainty, but eventually the piano’s dark reverberations, the high silvery violins and the aspiring ascents of cello and viola dissolve into stillness and peace.

If I have spent a long time describing The Western Playground it is because Gurney’s cycle, and even more so this brilliant performance by Williams, Dussek and the Bridge Quartet, make this disc an absolute must-have, not just for Gurney aficionados but for all lovers of English song, indeed all song. But, Those Blue Remembered Hills offers much more too.

There are four songs by Herbert Howells, including ‘There was a Maiden’ and ‘Girl’s Song’ from Fours Songs Op.22 (1916). In the first, Williams seems to inject a tint of wisdom into his baritonal warmth - a note of maturity to balance the shimmering melancholy of the piano’s oscillating patterns. Here, the baritone’s verbal pointings add much to the simple strophic form: “The cold wind blows across the lea”, sending a shiver through one’s spine, while the description of the maiden, “pale, so pale, with never a rose”, makes one fear for the vulnerable lass. ‘Girl’s Song’, brimming with desire and visceral feeling, may last less than 90 seconds, but Williams and Dussek offer a masterclass in musical articulation and expression. Howell’s setting of a text by Northumbrian poet Wilfrid Gibson, ‘The Mugger’s Song’, is an unpretentious, boisterous rural character-study, precisely drawn here; best of all is the compelling directness and simplicity of ‘King David’, with its ‘antique’ modal and pentatonic tints. Both Williams and Dussek rise to tremendous heights of eloquent expression.

The Bridge Quartet

The Bridge Quartet

There are further songs by Gurney too, the ballad ‘Edward, Edward’ - a setting from the Reliques of Thomas Percy, in which Williams’ has a good stab at Scots brogue - and one of Gurney’s best-known songs, ‘By a Bierside’ (a song which was orchestrated by Howells), which Gurney’s Collected Letters (ed. R.K.R. Thornton) reveal ‘came to birth in a disused Trench Mortar emplacement’ and which brings the disc to a close. Williams’ demonstrates that his wistful head voice, bold middle range, and probing deep bass-like resonance are equally affecting. I could literally feel the thunderous shine of Williams’ proclamation of John Masefield’s final words, “It is most grand to die”, pulse in my heart, before the tranquil repetition “so grand” quietened the passion. Heracleitus had included an Adagio for string quar1tet played by the Bridge Quartet, which is an earlier version of the D Minor String Quartet heard in full on this disc - a world premiere recording.

Why is it that these English poets and composers - Georgians and Edwardians - seem to speak so strongly to us still? I don’t think that it is simply that they console, or feed, a nostalgia for an Edwardian twilight, more that there are times, in any age and place, when we long for what we imagine was a simpler age.

In a letter to his friend Marion Scott (musicologist, poet, composer, violinist and more) dated December 1916, Gurney reflected on life in the trenches in France: ‘After all, my friend, it is better to live a grey life in mud and danger, so long as one uses it - as I trust I am now doing - as a means to an end. Someday all this experience may be crystallized and glorified in me; and men shall learn by chance fragments in a string quartett [sic] or symphony, what thoughts haunted the minds of men who watched the darkness grimly in desolate places.’ This recording confirms that Gurney did indeed crystallise and glorify those experiences in words and music.

Before listening to this disc, I could not imagine anyone who could better capture the poignancy of that suffering, and the beauty which rises from it, and transcends it, than Roderick Williams. Having listened to Those Blue Remembered Hills, I do not think that Williams has done anything finer.

Claire Seymour

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Blue%20Remembered%20Hills.jpg image_description=EMRCD065 product=yes product_title=Those Blue Remembered Hills product_by= Roderick Williams (baritone), Michael Dussek (piano), The Bridge Quartet (Colin Twigg and Catherine Schofield [violins], Michael Schofield [viola], Lucy Wilding [cello]) product_id=EM Records EMRCD065 [80:52] price=£13.00 product_url=https://www.em-records.com/discs/emr-cd065-details.htmlJune 26, 2020

Eboracum Baroque - Heroic Handel

The ensemble does perform in London, but it has also generated quite a presence for itself outside the metropolis, with regular concerts in York and in Cambridge, as well as performing at National Trust properties in programmes which reflect the musical history of each property. The group’s 2015 disc of the music of 18th-century composer Thomas Tudway was recorded at National Trust’s Wimpole Hall where Tudway worked from 1714 to 1726.

Since Lockdown, the group has been active online, giving a regular series of coffee concerts of solo repertoire on Zoom. But, as Chris Parsons explained when we chatted recently over Zoom, the group has been ‘chomping at the bit’ to do something larger scale. They had a live concert planned for July 2020, so as this was cancelled the group decided to do something similar, online. Thus, Eboracum Baroque's Heroic Handel concert was born, to be streamed on YouTube and Facebook on Saturday 18 th July 2020 at 7pm.

As well as giving the musicians a chance to perform, the concert represents an opportunity to provide them with some welcome financial support, as well as keeping the audience engaged. Chris points out that it is important not to forget that people are waiting to come to concerts. The group’s virtual coffee concerts, which happen every couple of weeks, have enabled the musicians to maintain links with regular supporters in the UK but also to develop an audience from all over the world. The virtual concerts arose partly out of an idea that they had had already: to do concerts which placed individual Baroque instruments in the spotlight. And, this has happened, albeit in online rather than live. Chris admits that there is a personal element, too, in the move to larger-scale repertoire; his own instrument is the trumpet and there is not too much Baroque repertoire for just trumpet and continuo.

The logistics of presenting larger-scale repertoire online have been significant, and it has been a real learning curve. Thankfully one of Chris’ friends is something of a tech whizz, but it has required Chris to mark up the music in a detailed fashion, something he would not normally need to do, so that they could create click tracks with all the tempo variations. And then there was getting used to the strangeness of playing along to just a click track. In fact, they recorded the cello and harpsichord continuo first, layering everyone else over the top. But it has given Chris and the other musicians in the group a big project to be working on, particularly as the planned concert will have about 60 minutes of music.

The repertoire for the concert, all by Handel, celebrates all the different aspects to Eboracum Baroque's performances, with the coronation anthemZadok the Priest, arias from Rinaldo and Giulio Cesare, a chorus from Acis and Galatea, a trio sonata and a recorder sonata, all starting with a March from Rinaldo. Chris describes it as a real mixed bag, and there is deliberately something for everyone.

The group is hoping to create, as closely as is possible, a concert ambience, even suggesting that audience members dress up for the occasion, and there will be an interval during which York Gin will talk about the history of gin, and be making a virtual cocktail!

The group is also working on further virtual concerts to make up for the continuing enforced live silence. Their next recording project was going to be the recorder version of Vivaldi's The Four Seasons, something that Chris describes as mind-boggling. This has been delayed, and they hope it might kick off later this year or early next year.

They are also thinking about Christmas 2020. For a small group, Christmas is an important part of the calendar; performances such as Messiah in Cambridge with an audience of around 600 people effectively make the group’s other work possible. Without such large-scale performances, they are looking at other ideas, such as streaming.

Messiah - Senate House, Cambridge.

Messiah - Senate House, Cambridge.

Other projects which have been hit by lockdown included the ensemble's education work. In May 2020, they were due to be doing a schools’ projects on Vivaldi's Four Seasons at the National Centre for Early Music in York. Instead, they are looking videos and online sessions to replace these, and hope to be releasing something in the autumn.

Eboracum Baroque in fact began as a choir, and it then morphed into a mixed group which performs everything from chamber music, orchestral music and opera. It is very much a group of friends, most now in their mid- to late-20s. Chris sees the group as providing a musical platform for young musicians, performing great repertoire and valuable income for young freelance musicians. Now that that musicians are slightly, older many are also working in some of the major early music ensembles.

Around five or six years ago, the group was doing a free concert at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge when Chris was approached by someone from the National Trust. They were interested in the composer Thomas Tudway (before 1650-1726), who had worked at the National Trust's Cambridgeshire property Wimpole Hall. Chris did some research and found that there seemed to be a great deal to Tudway. The upshot was a disc of Tudway's music, recorded in the chapel at Wimpole Hall and funded by the National Trust and Arts Council England.

Vivaldi in York.

Vivaldi in York.

Chris would like to be able to return to Tudway as he feels that a lot of Tudway’s music is good; there is a piece for full orchestra which Tudway wrote for his graduation at Cambridge and which intrigues. Chris finds Tudway an amazing and interesting person but thinks that perhaps he was too outspoken for his own good; Tudway was organist at King's College, Cambridge for over 50 years but never managed to get a post in London.

One of the things that Chris enjoys doing with Eboracum Baroque is finding composers who need a platform. Another instance of this is the mid-18th century Suffolk composer, Joseph Gibbs (1699-1788) who was as celebrated as Handel in his native Ipswich. A lot of Gibbs’ music does not survive, and we only have his violin sonatas, but Eboracum Baroque has recorded some of them on a disc entitled Sounds of Suffolk, alongside music by Giovanni Bononcini (1670-1747), Gottfried Finger (1655-1730) and Charles Dieupart (1667-1740), all composers with links to Suffolk. Bononcini has links with Ickworth House where he worked for the Hervey family, while Charles Dieupart taught the Hervey children.

Another regional music making project involves looking at large-scale odes for St Cecilia’s Day with Bryan White of Leeds University (who has written a book about music for St Cecilia across the British Isles in the 17th and 18th centuries), with music by George Holmes (1680-1720), organist of Lincoln Cathedral and Vaughan Richardson (died 1729), organist of Winchester Cathedral, again lesser known names which deserve more of a platform. They have already performed some of this repertoire with Bryan White conducting the Leeds University Chamber Choir, and there are plans in the works for a CD.

Eboracum Baroque has only been part of Chris’ life; as well as freelancing on the trumpet (mainly Baroque), he also spends two days a week teaching, and he is lucky that this has continued via Zoom. He lives just outside Ely, and this has led him to develop local connections. He conducts two amateur orchestras and a choir in the area, and really enjoys working with them. Continuing rehearsing under lockdown has involved Chris in conducting rehearsals online and making virtual recordings; he describes this as an eye-opening process.

He has found that rehearsing via Zoom is good for talking about details, marking up the music and making sure that performers understand, and the orchestras have worked a lot to backing tracks. An important part of this process is that it ensures that individual players and singers are not left alone, they have something to perform along with. And the last half-hour of each session has a different member each week presenting their own version of Desert Island Discs. Whilst the process has been limiting in some ways, Chris sees it as opening up new doors, but it will be amazing when they can meet up again.

Heroic Handel - Saturday 18th July 2020, 7pm Eboracum Baroque

March from Rinaldo, HWV7

‘O The Pleasure of the Plains’ from Acis and Galatea, HWV49

‘Sibilar gli annui d’Aletto’ from Rinaldo HWV7 (with John Holland

Avery, baritone)

Sonata in B Minor, Op.2 No.1, Andante and Allegro, HWV386

‘V’adoro, pupille’ from Giulio Cesare, HWV17 (Charlotte Bowden.

soprano)

Recorder Sonata in F Major, HWV369

Zadok the Priest

: Coronation Anthem for George II, HWV258

https://www.facebook.com/EboracumBaroque/ https://www.youtube.com/eboracumbaroque

image=http://www.operatoday.com/HeroicHandelPoster.png image_description= product=yes product_title=Eboracum Baroque: Heroic Handel, Saturday 18th July 2020, 7pmJune 22, 2020

Opera Rara at 50: Anniversary talk and Live Q&A

Tune in via Opera Rara’s Facebook for the talk and live Q&A here.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Opera%20Rara%2050.jpgIestyn Davies and Elizabeth Kenny bring 'sweet music' to Wigmore Hall

At first glance their programme looked fairly conventional and predictable. And, as has been the case with all the other vocal recitals in the series that I’ve watched, it focused on the work of English composers, in this case from the 16th and 17th centuries - though Davies and Kenny had a few surprises up their sleeve.

But, it was with the Orpheus Britannicus, Henry Purcell, that we began. And, I can think of few who communicate the ‘essence’ of this music more movingly or perceptively than Davies. His plea for music, “Strike the viol, touch the lute, wake the harp” (from Come, ye songs of art away, the last of six birthday Odes written for Queen Mary), was a luring, liquidy invitation, the section repeats temptingly ornamented vocally and showcased by Kenny’s rhythmically taut but understated accompaniment. ‘By beauteous softness mixed with majesty’, from the first birthday Ode, offered more delicate, muted reflections, Kenny’s lute spinning a translucent spider’s web of interlocking voices and Davies’ countertenor gliding through the sequential repetitions and variants with soft smoothness. “He with such sweetness and justness reigns”: it was impossible to disagree. Davies is able to expand, colour and enrich his voice at the click of an invisible switch and to integrate such flourishes within what one would imagine to be an impossibly even line.

The duo segued into ‘Lord, what is man?’, reaching deeper into the metaphysical profundity of the seventeenth century. There was a wonderful introspective quality at the start, but as the tessitura and the emotional scope enlarged - the frequent vocal leaps were effortlessly elided - the music pushed towards the triple-time “O for a quill” acquiring an ever more optimistic tone, and finally blooming in the concluding Hallelujah section. I can imagine many of the current superb bunch of international countertenors rattling off the virtuosic runs with equal accuracy, but few who would do so in the service of the music with such insight, daring to hold back, to tempt and invite with Purcell’s bravura, rather than to dazzle. No wonder Kenny allowed herself the briefest of smiles at the close.

Kenny closed the Purcell sequence with her own arrangements of a brusque Rigadoon, a contemplative Farewell and a nonchalant ‘Lillibulero’, her playing always lucid and tender as she stroked and plucked her beautiful theorbo’s strings with care and understanding, nurturing Purcell’s music into being.

John Dowland, Thomas Campion and Robert Johnson followed. The strophic suavity of ‘Behold a wonder here’ and ‘The sypres curten of the night is spread’ beautifully illustrated the compelling unity of vocal directness and the affective tracery of the lute achieved by Dowland and Campion, respectively. Davies found particularly expressive nuance in Campion’s song, sustaining the melancholy introspection while simultaneously searching through turbulent emotions, as Kenny provided a delicate lace-work tapestry to support the singer’s sombre but silken reflections. Davies was no less musical and articulate in conveying the more declamatory rhetorical intimations of Dowland’s ‘Sorrow, stay, lend true repentant tears’. Campion’s agile ‘I care not for these ladies’ found the performers in more nonchalant, but no less perceptive, mood. Kenny interleaved a Fantasia by Johnson, Dowland’s dynamic King’s Galliard and a brisk Corante by the intriguing ‘Mr Confess’.

Then came the unexpected. We shifted forwards 100 years. Mozart’s songs are not usually considered central to his oeuvre (somewhat surprising, perhaps, given his mastery of every genre of contemporary opera) but the lied ‘Abendempfindung’, composed in June 1787, less than a month after his father Leopold’s death, exemplifies the art of understated eloquence. The poet-speaker sings of his presentment of his inevitable death to the Petrarchian ‘Laura’, pleading with her to shed a tear on his grave which will be the “fairest pearl” which he takes to his heavenly refuge. Kenny’s French guitar lilted lightly through the simple arpeggio-accompaniment, while Davies expressed the depth of the poetic feeling without vocal or expressive mannerism. The candour was the performance’s power.

Finally came Schubert. ‘Heidenröslein’ was deliciously light and insouciant, with some wonderfully shaped rubatos and diminuendos. Quite honestly, I could listen to Davies’ mellifluous, subtly expressive performance of ‘Am Tage aller Seelen’ on a 24-hour loop. If you needed convincing that a countertenor can make a Schubert lied ‘speak’ here was your evidence. Kenny knew absolutely where and when to come to the fore and when to recede. By this point in the recital, I’d run out of superlatives, so Opera Today readers will have to imagine for themselves, or watch via the link below.

And, an encore to close: Handel’s ‘Hide me from day’s garish eye’ from L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato. As Davies explained, Milton’s text expresses the hope that, after seeming to have lived a terrible dream, when man awakens sweet music will breathe, and continue to breathe. So do we all, so do we all.

Claire Seymour

This concert is available here and via BBC Sounds until 22 July. Wigmore Hall's live stream of this concert was supported by Hamish Parker.

Iestyn Davies (countertenor), Elizabeth Kenny (lute)

Purcell - ‘Strike the viol, touch the lute’ (from Come, ye sons of art, away Z323), ‘By beauteous softness mixed with majesty’ (from Now Does the Glorious Day Appear Z332), ‘Lord, what is man?’ (A Divine Hymn Z192), Rigadoon (arr. Elizabeth Kenny), ‘Sefauchi’s Farewell’ Z656 (arr. Elizabeth Kenny), ‘Lillibulero’ Z646; Dowland - ‘Behold a wonder here’; Campion - ‘The sypres curten of the night is spread’; Johnson - Fantasia; Dowland - ‘Sorrow, stay, lend true repentant tears’, ‘The King of Denmark, his Galliard’; Campion - ‘I care not for these ladies’, Anon - ‘Mr Confess’ Coranto’; Mozart - ‘Abendempfindung’ K523; Schubert - ‘Heidenröslein’ D257, ‘ Am Tage aller Seelen’ D343.

Wigmore Hall, London; Monday 22nd June 2020.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Kenny%20and%20Davies.jpg image_description= product=yes product_title=A live recital from Wigmore Hall by Iestyn Davies (countertenor) and Elizabeth Kenny (lute) product_by=A review by Claire Seymour product_id=Above: Elizabeth Kenny and Iestyn DaviesJune 18, 2020

Bruno Ganz and Kirill Gerstein almost rescue Strauss’s Enoch Arden

Mozart was moved to compose one in the Benda style but abandoned it. Schumann got rid of the orchestra altogether and reduced the melodrama to a single instrument - the piano. What Weber, Benda and Beethoven did with melodrama was focus and magnify in a shortish scene on someone’s horror, terror, or psychological disintegration.

Richard Strauss changed all that and, it is almost universally acknowledged, not for the better. Enoch Arden certainly doesn’t lack a first-rate text - it is after all written by Tennyson. Its narrative is not without drama or emotional impact, either. Arden, a sailor, leaves his family to go on a voyage in order to financially support them (though, depending on how you read Tennyson’s poem this can be interpreted in another way). He is shipwrecked on a desert island with two companions who later die; Arden is left alone, lost and marooned for ten years. After he is rescued, he arrives back to find his wife has remarried Arden’s best friend, Philip, and has given birth to another child after long believing Arden to have perished. Rather than ruin her happiness he never reveals he is alive and dies of a broken heart. There is so much tragedy here Strauss should have been able to have made something remarkable from it. He didn’t.

Tennyson’s literary influences - almost inserted into his poem like leitmotifs, of which the piano part has many - are some of the most vivid examples of creative genius. Homer’s Odyssey, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, the Biblical Enoch, and, to a lesser extent, Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. If his Arden is not a particularly mythological character, he is certainly one with masculine identities. This is an Arden who is daring, adventurous and ambiguously selfless. It is a contrast which Strauss could have used to some effect as a dramatic foil against the dependable Philip Ray, or the wife, Annie, who can barely find a husband outside a narrow triangle.

So, what went so wrong for Strauss in Enoch Arden? Length is certainly an issue (performances can run just short of an hour). There is also no Hoffmansthal to help Strauss out; rather, we have a translation of Tennyson’s verses by Albert Strodtmann, one of the twelve translators of this poem since the poem’s publication in Germany in 1867. Strauss may well have been directly influenced by the 1895 Arden opera by Viktor Hansmann or, more likely, Strodtmann’s third edition translation with Thumann’s illustrations (a picture is so often worth more than a thousand words). Another problem for Strauss might have had less to do with the masculinity of Arden himself and more to do with the characterisation of Annie and how she is developed in Tennyson’s poem.

Enoch Arden was composed in 1897 - a time when Strauss was writing his great Tone Poems like Don Juan, Macbeth, and Tod und Verklärung and yet what you get in the melodrama is some of Strauss’s soggiest and most sentimental music. Strauss would compose Ein Heldenleben just a year later, in 1898, a work with its strong feminist line in the violin solos which depict his wife, Pauline. Within a decade, Strauss would have pushed the melodramatic feminine psyche to the absolute limit and beyond in his two ground-breaking operas, Salome and Elektra. But Enoch Arden had none of this revolutionary zealousness and perhaps it simply suffocated Strauss’s creativity because of it. Viewed in Germany as “spineless”, a woman’s poem, it was perceived as a matrimonial tragedy which appealed only to the prurience of women. A view became cemented that this was a poem which celebrated bigamy and a certain kind of immorality. This would almost certainly have seemed old-fashioned to the younger Strauss who was standing at the door waiting to write some of the most radical operas to open any new century.

If the music and its structure fails what you have left are the performers and this is where Enoch Arden has been somewhat lucky. As in any melodrama it is the voice which is going to carry the poem and dating back to the first recording in 1962 with Claude Rains and Glenn Gould some quite remarkable narrators have made a recording. Almost without exception the greatest recordings of Enoch Arden have been made by actors rather than singers - Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, whose recording followed that of Rains, Jon Vickers in 1998 (and his debut role as a speaker) and Benjamin Luxon in 2007 lack the one thing that this part needs: the ability to dramatize. You really wouldn’t want any of these singers to read a book to you at bedtime - especially Vickers. Much more interesting are the recordings by Rains, Gert Westphal, Michael York, Patrick Stewart and this brand new recording by the late Swiss actor Bruno Ganz.

I’m not sure one would ever have thought of Claude Rains as a particularly masculine actor, though the mystery he brings to his reading of Arden has everything to do with an actor who could so clearly have worked wonders in James Whale’s 1933 film The Invisible Man. Bruno Ganz, on the other hand, is an entirely different kind of actor. His Arden is a study in 1930s expressionism, but it is also borne out of Goethe’s Faust. This is probably the deepest, most tragically drawn portrait of Enoch Arden on disc, and I am not sure you have to be fluent in German to sense that.

But you also feel that Ganz is extremely comfortable here - it recalls his beautifully rendered work on Abbado’s 1993 recording of Nono’s Il canto sospeso with the Berlin Philharmonic. So much of this work is sectionalised by Strauss, that it can almost feel like trunks of text stitched rather badly to chords of piano writing and not much that joins them together. Vickers rather surprisingly finds himself out on a limb here, almost as if he has to be prompted by his pianist, the excellent Marc-André Hamelin (though this perhaps is a singer’s typical response). Rains and Ganz, on the other hand, aren’t phased by these elliptical dropouts so both their pianists seem to follow them rather than the other way around.

Kirill Gerstein, like Glenn Gould before him, doesn’t do understatement and Strauss doesn’t really give this long work any kind of architectural frame to hold it up; rather, it relies on its pianist to improvise a little to disguise the work’s technical problems. Both Gould and Gerstein bring enough style and brilliance to their playing to make any shortcomings the work may have seem minor, though it would also be true to say with almost any other actor/narrator than the one each is paired with on their respective recording the dynamic of the performance would completely change. This is foremost a work which is about the narrator.

There are now some twenty or so recordings of Strauss’s Enoch Arden, most of which were recorded after the 1990s when the work really did seem to go through some kind of revival. There are versions in several languages, including English, German and Italian. No English language version comes close to the first, the 1962 recording with Claude Rains and Glenn Gould (Columbia, nla). This most recent version by Bruno Ganz and Kirill Gerstein is a clear first choice for a German language recording of Tennyson’s poem but edges out the Rains/Gould for at least two reasons.

Firstly, Ganz brings a kind of Herzhog-like depth to his narration which goes well beyond the narrative itself. This is a reading which is as simple as the words Ganz is speaking; but it is also an inspired allegory, a map through theological symbolism, a deep rendering of one man’s elegy and tragedy. This recording turned out to be Bruno Ganz’s final work but in that one could now read different interpretations of this performance. For Kirill Gerstein, his playing lacks none of the intensity that Glenn Gould brought to his recording almost sixty years ago; what differs, is that Ganz’s darker German reading of the text allows Gerstein to follow his narrator into those rather gloomier corridors largely eschewed by others.

Strauss’s Enoch Arden was, in my view, one of those Strauss works that was shipwrecked over a century ago and has yet to be properly rescued. This Ganz/Gerstein recording is the closest - and might be the closest - we get to rescuing this long-marooned work. Just not yet, though. Just not yet.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Enoch%20Arden.jpg image_description=MYR025 product=yes product_title=Richard Strauss: Enoch Arden Op.38 product_by=Bruno Ganz (narrator), Kirill Gerstein (piano) product_id=Myrios Classics MYR025 [CD] price=$19.99 product_url=https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B084DHD4BQ/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=B084DHD4BQ&linkCode=as2&tag=operatoday-20&linkId=3b139c07f928fd38b280603e7c533264June 17, 2020

Strauss – Ariadne auf Naxos

Only a few months following the premiere of Der Rosenkavalier, Hugo von Hofmannsthal proposed a new opera to Richard Strauss based on Molière’s comedy-ballet, Le Bourgeois gentilhomme (in German, Der Bürger als Edelmann).

As initially conceived, the work was in two parts—the first being an adaptation of Le Bourgeois gentilhomme with incidental music composed by Strauss and the second being a collision of an opera seria based on the legend of Ariadne with commedia dell’arte, which would replace the Turkish ceremony with which Molière’s play ends. The work was completed in April 1912 and premiered in Stuttgart the following October. As Charles Osborne notes:

The first night, on October 25, was something of a disaster. Though the press reports were in general favourable, the audience received the Molière-Hofmannsthal-Strauss mélange without enthusiasm. Those who had come to enjoy Molière were bored by the opera which was tacked on at the end of the comedy, while the opera-goers who had come to hear Strauss’s latest opera were vexed at having first to sit through a play by Molière.

[Charles Osborne, The Complete Operas of Strauss, London: Grange Books, 1992]

Eventually, the work was revised with the first part being entirely rewritten as a prologue to the opera. The location was changed from Paris to Vienna, all dance scenes were eliminated and the plot bears but scant resemblance to Molière’s play. The incidental music that Strauss had composed would reappear later as Le Bourgeois gentilhomme Suite (1920).

As revised, Ariadne auf Naxos premiered at the Hofoper in Vienna on 4 October 1916.

Synopsis

Prologue

In the house of the richest man in Vienna, where a sumptuous banquet is to be held in the evening, two theatrical groups are busy preparing their entertainments. The Music Master protests to the Major-domo about the decision to follow his pupil's opera seria, Ariadne auf Naxos, with 'vulgar buffoonery'. The Major-domo makes it plain that he who pays the piper calls the tune and that the fireworks display will begin at nine o'clock. The Composer wants a last-minute rehearsal with the violinists, but they are playing during dinner. The soprano who is to sing Ariadne is not available to go through her aria; the tenor cast as Vacchus objects to his wig. There is typical backstage chaos. Seeing the attractive Zerbinetta and inquiring who she is, the composer is told by the Music Master that she is leader of the commedia dell'arte group which is to perform after the opera. Outraged, the Composer's wrath is turned aside when a new melody occurs to him. The Major-domo returns to announce that his master now requires both entertainments to be performed simultaneously and still to end at nine o'clock sharp. More uproar, during which the Dancing Master suggests that the Composer should cut his opera to accommodate the harlequinade's dances.

The plot of Ariadne is explained to Zerbinetta, who mocks the idea of 'languishing in passionate longing and praying for death'. To her, another lover is the answer. Zerbinetta and the Composer find they have something in common when Zerbinetta tells him 'A moment is nothing - a glance is much'. 'Who can say that my heart is in the part I play?' Heartened, the Composer sings of music's power. But when he sees the comedians scampering about, he cries, 'I should not have allowed it.'

Opera

On the island of Naxos, where Ariadne has been abandoned by Theseus, who took her with him from Crete after she had helped him to kill the Minotaur. Ariadne is asleep, watched over by three nymphs, Naiad, Dryad and Echo. They describe her perpetual inconsolable weeping. Ariadne wakes. She can think of nothing except her betrayal by Theseus and she wants death to end her suffering. Zerbinetta and the comedians cannot believe in her desperation and Harlequin vainly tries to cheer her with a song about the joys of life. She sings of the purity of the kingdom of death and longs for Hermes to lead her there. The comedians again try to cheer her up with singing and dancing, but to no avail. Zerbinetta sends them away and tries on her own, with her long coloratura aria, the gist of which is that there are plenty of other men besides Theseus. In the middle of the aria, Ariadne goes into her cave. Zerbinetta and her troupe then enact their entertainment in which the four comedians court her.

The three nymphs excitedly announce the arrival of the young god Bacchus, who has just escaped from the sorceress Circe. At first he mistakes Ariadne for another Circe, while she mistakes him for Theseus and then Hermes. But in the duet that follows, reality takes over and Ariadne's longing for death becomes a longing for love as Bacchus becomes aware of his divinity. As passion enfolds them, Zerbinetta comments that she was right all along: 'Off with the old, on with the new.'

[Source: Australian Broadcasting Corporation]

Click here for the full text of the libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/John_Vanderlyn_001.png

image_description=The Sleeping Ariadne in Naxos by John Vanderlyn [Source: Wikipedia]

audio=yes

first_audio_name=Ariadne auf Naxos

first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Ariadne2.m3u

product=yes

product_title=Richard Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos

product_by=Gabriela Benackova-Cap (Primadonna/Ariadne), Edita Gruberova (Zerbinetta), Ann Murray (Komponist), Wolfgang Schmidt (Tenor/Bacchus), Peter Weber (Musiklehrer); Das Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper, Horst Stein (cond.)

Live performance, 20 April 1996, Weiner Staatsoper, Vienna

product_id=Above: The Sleeping Ariadne in Naxos by John Vanderlyn [Source: Wikipedia]

Spontini – La Vestale

Music composed by Gaspare Spontini. Libretto by Etienne de Jouy.

First Performance: 15 December 1807, the Opéra, Paris

| Principal Characters: | |

| Licinius, a Roman general | Tenor |

| Cinna, commander of the legion | Tenor |

| The Pontifex Maximus | Bass |

| The Chief Soothsayer | Bass |

| A Consul | Bass |

| Julia, a young Vestal virgin | Soprano |

| The High Priestess | Mezzo-Soprano |

Setting: Republic of Rome, c. 269 B.C.E.

Synopsis:

Act I

The young commander, Licinius, has returned to Rome in triumph. Nonetheless, he is filled with dread. He tells his friend, Cinna, that his beloved Julia joined the cult of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth, while he was in Gaul. Julia asks the head priestess that she not be present during the commander’s honor; but, her request is denied. As Julia presents Licinius with the golden wreath, he whispers to her that he plans to abduct her that evening.

Act II

Julia stands watch before the sacred flame, which must never go out. She prays to Vesta for deliverance from her sinful love. Yet, she races to open the temple doors to allow Licinius entry. When Licinius arrives, he swears to free her from her obligations. The sacred flame goes out as they pledge mutual fidelity. Cinna warns Licinius to escape at once. The Pontifex Maximus arrives and accuses Julia of perfidy. He demands to know the name of the intruder. Julia refuses to name Licinius. She is then cursed, stripped of her garments and sentenced to death.

Act III

Julia is to be buried alive. Licinius and Cinna plead for mercy. The Pontifex Maximus is unyielding. Licinius confesses that he is to blame; but Julia claims that she does not know him. She is led before the altar and climbs down into the open grave. A storm envelopes the temple. A lightning bolt ignites Julia’s veil that had fallen near the altar and the sacred flame is rekindled. Licinius and Cinna rescue Julia from the grave. The High Priestess recognizes divine intervention. All are forgiven. Julia is freed from her vows. Licinius takes Julia’s hand and leads her to the altar where they are married.

Click here for the complete libretto.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Henri-Pierre_Danloux_-_Le_supplice_dune_vestale_%281790%29.png image_description=Le supplice d'une vestale (1790) by Henri-Pierre Danloux (1753-1809) [Source: Wikipedia] audio=yes first_audio_name=Gaspare Spontini: La Vestale first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Vestale1.m3u product=yes product_title=Gaspare Spontini: La Vestale product_by=Leyla Gencer (Julia), Renato Bruson (Cinna), Robleto Merolla (Licinius), Agostino Ferrin (The Pontifex Maximus), Franca Mattiucci (The High Priestess), Sergio Sisti (The Chief Soothsayer), Enrico Campi (A Consul), Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Massimo di Palermo, Fernanco Previtali (cond.)Live performance, 4 December 1969, Palermo (sung in Italian) product_id=Above: Le supplice d’une vestale by Henri-Pierre Danloux (1790) [Source: Wikipedia]

Longborough Festival Opera launches opera podcast

The Longborough Podcast offers listeners the opportunity to hear directly

from the artists and figures at the forefront of the industry. Each episode

will explore a particular composer, work or role, welcoming friends from

the world of opera and the arts - including singers, players, directors,

conductors and more - for some thought-provoking discussions.

The first few episodes include:

1. Music journalist Richard Bratby, Longborough Music

Director Anthony Negus and bass-baritone Paul Carey Jones trace Wotan’s journey through Wagner’s

Ring cycle.

2. Writer and librettist Sophie Rashbrook, sopranoLee Bisset and historian Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough explore the roles of women in

Wagner’s Ring cycle.

3. A conversation about The Cunning Little Vixen in context of Janacek’s

works, hosted by Richard Bratby.

4. Opera director and librettist Sir David Pountney and Longborough’s

Artistic Director Polly Graham uncover the use of comedy in Wagner’s Ring

cycle.

Listen to the first episode here: https://lfo.org.uk/our-story/podcast

Longborough Artistic Director Polly Graham comments:

“What we hope to achieve from this podcast is a chance to open up some

of the amazing works we had programmed for 2020, and to celebrate the

thinking of the artists we work with. The lockdown has been hugely

challenging for the performing arts, but it has given us the

opportunity to think creatively about different experiences we can

still offer audiences. We miss our audiences so much and cannot wait to

connect with them again through live theatre and music. In the

meantime, we hope this podcast will continue to feed their imagination.

We are so grateful for their continued support at such a challenging

time.”

The news comes following the success of Longborough’s recent fundraising

campaign that generated £300,000, two-thirds of which went directly to the

freelance artists involved in the postponed 2020 festival’s four

productions. The remainder will help to develop further work for artists