June 28, 2010

Jay Reise: An Interview by Tom Moore

His opera Rasputin, originally commissioned by Beverly Sills and the New York City Opera, was revived in 2008-09 by the Helikon Opera in Moscow. Rasputin will be given its Paris premiere by Opéra de Massy in November 2010. A new opera, based on the famous Strindberg play The Ghost Sonata, is under way. His violin concerto The River Within was premiered in 2008 by Maria Bachmann and Orchestra 2001 and is scheduled for release on Innova Recordings later this year. We talked by phone on January 20, 2010 with an email follow-up in June.

TM: Please talk about the musical background in your family.

JR: Both of my parents were very musical though neither was a professional musician. My mother was my first piano teacher when I was five and then my father started teaching me. He had studied with Rudolf Ganz at Chicago Musical College, and then subsequently with Eric Itor Kahn and Irma Wolpe in New York. All three were quite formidable teachers: Ganz had studied with Busoni and is the dedicatee of Ravel’s Scarbo as well as Griffes’ The White Peacock and piano sonata; Kahn was a student of Schoenberg and had given the world premiere of Klavierstücke Op. 33a; and Wolpe, one of the most celebrated teachers at that time, had worked with Cortot and was of course Stefan Wolpe’s first wife. That’s quite a mixture of national musical cultures to introduce to a kid from Sparks, Nevada in the late 1940s! And I was fortunate to have something of it passed down to me. My dad eventually went on in business but is still an accomplished and enthusiastic amateur pianist.

The main focus of my parents was on classical music but they were also involved in jazz in the early 1950’s. My father was good friends with composer George Russell and copied music for George at the time when he was formulating what became his Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization. So my parents were wonderful mentors, embracing both the classical and jazz worlds.

I was, however, always most taken with classical music. I feel that I have known some of it all my life — which I guess I have since my Dad was always practicing it. I can’t remember when I didn’t know some pieces. They became a part of me. In a certain sense I sometimes feel like some of those composers are members of my family, like uncles. When I hear certain pieces by Schumann or, say, the Brahms B♭ minor Intermezzo (Op. 117 No. 2) it sort of feels like a dear relative is back visiting again. I was an only-child so maybe that’s what gives me a peculiar sense of who my relatives are!

TM: You grew up in New York City?

JR: I grew up in Queens and then Staten Island but visited Manhattan all the time. Even though I was quite smitten with classical music as a teenager - listening constantly, studying scores and I even took a few piano lessons with Irma Wolpe — my heart was in literature. I was more interested in becoming a writer, a dramatist in particular. In high school I was especially taken with the Theater of the Absurd, which was very big in the sixties. I read all of Beckett’s works, Ionesco, Pinter — the whole lot — I really thought I would go into literature at that point. I guess writing my own librettos is where that interest finally led.

I went to Hamilton College in upstate New York and was an English major, still pursuing the literary idea. At that time, again through my parents, I also became very good friends with jazz clarinetist and composer Jimmy Giuffre. Jimmy is of course one of the great legends of jazz — he passed on about two years ago. He was a remarkable fellow — candid and subtle, kind, complex, a splendid teacher and mentor, and a musician whose lyrical voice I think is unsurpassed.

It was in my junior year in college, during summer vacations and holidays that I began to study composition with Jimmy at his loft on West 15th street. Though I continued to be quite passionate about literature, I was spending more and more time on music. When I told Jimmy about this, he said in his quiet wise way, “Well…music chooses you.” It’s an insightful statement, one that I have passed on to many aspiring-but-not-quite-certain student composers. I studied with him for about two years, mainly doing counterpoint.

In my senior year at Hamilton I met Canadian composer Hugh Hartwell who was newly appointed to the faculty at sister school Kirkland College. He became a very significant mentor. He had studied with George Crumb, George Rochberg and Richard Wernick at the University of Pennsylvania and is also an excellent jazz pianist. We had many fascinating discussions on all sorts of things ranging from voice leading in Monteverdi to harmonic rhythm in Debussy to melodic development in Miles Davis. My musical horizons kept expanding. Hugh introduced me to George Crumb and Neva Pilgrim. Neva is a wonderful soprano who is a major champion of new music. She was a founder of the Syracuse Society for new Music, a leading new music ensemble which was just honored with an American Music Center Founders Award. Neva later sang the vocal part in my Symphony of Voices which was premiered at the Monadnock Festival in 1978.

After I graduated Hamilton I turned my goals towards a career in composition and went to McGill University in Canada. I worked with some really superb musicians at McGill — Bengt Hambraeus, a Swedish composer who was newly appointed, and Bruce Mather, who is a splendid composer and pianist. In 1973 I headed to the University of Pennsylvania and studied composition with Richard Wernick and George Crumb. I also studied harmony with George Rochberg who had gone into his “radical” tonal period with the Third String Quartet about two years before.

TM: Could you say a little more about theater in the sixties? Beckett is an enduring cultural influence, but Ionesco has somewhat faded from the public eye. What was it particularly that appealed to you about those playwrights?

JR: I agree with your assessment though I have not really kept up with current developments in theater. I am very fond of Ionesco — the whole business of the disintegration of meaning in language through clichés, anti-theatre, and his aggressive ridiculousness is to me quite different from Beckett’s world. They are both labeled as Theater of the Absurd although to me they have relatively little to do with each other. There are a few Ionesco plays that have a sort of Beckett loneliness to them like The Chairs and Exit the King. And I guess the torrent of words in The Unnamable and Lucky’s speech in Godot have a Ionesco-like quality. I was sorry to miss the Broadway production of Exit the King last year, which was a rare revival. I saw the New York premiere. It has always been my favorite of Ionesco’s plays — in some ways it is the most Beckett-like, with the main character eventually disappearing into the void — an even more minimal precinct than that of Godot. Both authors are very dramatic in their own ways. Beckett, to my mind, is a literary giant who probes to the deepest regions of human expression. I cannot think of anyone in the history of literature who is more imaginative than Beckett — greater perhaps, but not more original.

TM: Ionesco is in a sense more like Moliere — not so serious, more entertainment, more farce, closer to the questions of day-to-day.

JR: I think that’s generally true. But Ionesco can certainly deliver a powerful humanistic message — the swastika armband in La Leçon, the mute orator in Les Chaises.

TM: Could you talk about other formative musical experiences in the sixties in New York?

JR: I guess my first big breakthrough composer was Mahler in 1960 when I was 10 years old. That was the centenary of Mahler’s birth and Leonard Bernstein single-handedly brought about a Mahler renaissance. I saw the famous Young People’s Concert on Mahler and heard Bernstein conduct the Second Symphony. I also heard Dimitri Mitropoulos conduct the Ninth as well as Bruno Walter’s legendary Das Lied von der Erde with Maureen Forrester and Richard Lewis. All were at Carnegie Hall. I met Bruno Walter backstage after the performance and then wrote to him. He sent me back an autographed picture with a note which I still treasure. Another big childhood experience occurred somewhat earlier when I heard Russell Sherman play the Brahms d-minor concerto with Bernstein and the Philharmonic. I got both their autographs. All pretty heady experiences for a pre-teener!

I discovered Scriabin when I was about fifteen. This was when scores of his works were not easy to obtain, especially the later ones. I used to haunt a music warehouse in the Brill Building in Manhattan where I found ragged copies of early editions of Scriabin in rusty file cabinets. I brought them home like treasures, which indeed they were. Then Dover reprinted everything and now it’s all available online — what a wonderful thing that is!

For a young person who had explored only tonal music, it was very exciting to investigate this strange music at the edges of tonality — not yet the dissonant landscapes of Schoenberg and the Viennese, but still mysteriously tonal, a style that had evolved from tonality…. All that was a huge influence. What I later understood to be the evolution of the symmetrical French sixth chord in Scriabin’s Poèmes Op. 32 to its use as a component of the famous “mystic chord” in the late works considerably expanded my music theory horizons and compositional imagination. Later I wrote an article on Scriabin’s approach to symmetrical scales.1 His late works really spoke to me when I was a teenager, and continue to. In some ways that musical mystical ambience he created — I don’t mean his own mysticism, but the aura of his sound world— is certainly one of the reasons that I pursued music. There was an other-worldliness to his music, and I was powerfully attracted to it. I have enjoyed discussing this with Gunther Schuller who as a teen had a similar experience with Scriabin’s music and also for whom Scriabin has remained a passion.

So I guess altogether my artistic tastes at the time had something in common: I was drawn to music and literature that were classically based but challenged the boundaries of classical convention and at the same time had a powerful emotional impact.

TM: It’s gotten to be a long time ago, and people who may be reading this may have no personal memories of the nineties, let alone the sixties….one of the notable phenomena was the sort of musical event with a theatrical edge, what one might call “happenings”…were there events, or composers working in the avant-garde that were notable for you from that period?

JR: It’s interesting that you mention “happenings” since it was actually at a happening that I met Jimmy Giuffre. In about 1965 or ‘66, when I was in high school, I went to the Avant Garde Festival which was a series of happenings organized annually by cellist Charlotte Moorman that took place that year on the Staten Island Ferry. Moorman was quite famous — or infamous — at the time for having performed on the cello topless as part of a happening. A posse of police cars and the riot squad had showed up. She was arrested and eventually given a suspended sentence. The “piece” — the happening — therefore extended from the announcement of the performance itself, to the courthouse, to the coverage in the New York Times and the subsequent fallout. It was all pretty funny but it was obvious that the happening was about the theater of the event rather than anything to do with music. I remember Charlotte as an exceptionally nice person. She was totally committed to what she was doing and had great fun doing it. And since joy is something that can be hard to come by in 20th century art, I guess she was on to something.

With regard to happenings themselves, well, that brings up the whole topic of John Cage, Nam June Paik and all of those folks who were taking a radically different approach to music at the time. That path seemed to me at the time more Dada or anti-music and not headed in a direction I was personally interested in. I have little patience for Dada and its derivatives in general - the joke seems to me stale. On the other hand I recognize now that happenings were also the beginning of performance art which is of course a very important medium.

So anyway, among all the unusual, bizarre and crazy things going on that Saturday on the Staten Island Ferry was a performance by a jazz trio led by a superb clarinet player surrounded by a large audience. That’s when I first met Jimmy. He was moving past his very avant garde “free jazz” period at the time which culminated with the album Free Fall.

TM: Were there jazz idioms that particularly appealed to you in the sixties and seventies?

JR: I was very interested in Jimmy Giuffre’s music of course, especially in terms of his unique lyricism and special instrumental voicings. Also George Russell. Jazz piano always interested me, although I don’t play very much jazz piano and don’t write in a jazz style. I always liked Bill Evans a lot, Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Nat “King” Cole, Paul Bley, Monk. And of course all the great instrumentalists — Davis, Mulligan, Sonny Rollins, Clifford Brown. I could go on — but my list would not be news to anyone. Maybe some somewhat lesser known names, like pianists Jimmy Rowles, Denny Zeitlin.... My mother plays wonderful jazz piano with some of the most exquisite chord changes I have ever heard.

When I was three or four my parents used to go to sessions in George Russell’s apartment — I would sleep in the bedroom on the coats while the music making went on ‘til the wee hours. What I would give to have a second chance to hear that!

I attended a memorial service for George a few weeks ago. The music was phenomenal and was played by some of today’s best jazz musicians covering his work from the ‘50s to just a few years ago. Almost sixty years of music of tremendous variety but George Russell always sounded like himself and no other.

TM: Please talk a little about the musical atmosphere at McGill. These days we have a facility in having access to music from Estonia, or Latvia, or Russia that is just astonishing, but at that time to have a new composer from Sweden at McGill must have been unusual.

JR: I guess so though it did not occur to me, maybe because in Canada I was an outsider as well. Montreal is a five-hour car ride to New York or Boston but its closest cultural connections are with Paris. The McGill music faculty was very French-oriented, and France’s most well known composers at the time were of course Messiaen and Boulez.

During my undergraduate years I had become very interested in the music of Messiaen — probably my primary passion after my Scriabin period. I was blown away by Et Exspecto Resurrectionem Mortuorum which remains my favorite Messiaen multi-instrument work. I subsequently heard Yvonne Loriod perform the Vingt Regards sur L’Enfant Jésus at Hunter College as well as Messiaen and Loriod together playing his Visions de l’Amen. These were incredible experiences. Loriod was a magnificent pianist and her interpretation of standard literature like the Debussy Etudes was also a revelation.

Like Scriabin, Messaien used symmetrical scales and so inhabited a similar place at the edge of tonality. Both also had color-graphemic synesthesia as well as a strong dose of mysticism. When I had master classes with Messiaen at Tanglewood, I asked him about Scriabin’s harmony. He said that unlike Scriabin, he treated harmony only as a matter of taking down the music in the colors before him.

Both Bruce Mather and Bengt Hambraeus had studied with Messiaen. I didn’t go to McGill specifically for that reason, but the connection was certainly a plus. With Hambraeus I mainly studied orchestration. He was encyclopedic on contemporary techniques and a multitude of other things. He introduced me to such diverse things as the first version of Boulez’s Le Marteau sans maître and the unpublished Poésie pour pouvoir as well as the work of the great Russian conductor Nikolai Golovanov. Mather and I shared a love of Scriabin and his class in 20th-century harmony was truly extraordinary. We studied Scriabin, Debussy, late Fauré, Berg and wrote pieces in their styles, which is something I do in my own classes. But the first assignment was to write a Bach chorale: if you could not do that, you could forget the rest!

I had several pieces done at McGill as well as at a festival in Toronto; they were influenced by what I would now describe as French atonality along with some Berg. They were not serial — it was the time when serialism was beginning to lose its grip.

TM: Messiaen seems far more productive in the results that are evident in the composers that follow him than Boulez.

JR: Messiaen had such a wide scope — he was so all-encompassing and eclectic but incredibly original. Like Berg, he absorbed and transformed the 19th century musical phenomenon into his own inimitable style — and then took on bird song, plainchant, the Catholic faith, tonality and modality, symmetrical scales, atonality, fixed registers, Asian music and plainchant as well as other elements!

I have also always been a great admirer of Boulez, both his music and his writings. His style — in terms of his gestures and vocabulary — has expanded over the years but his “sound-print” is always unmistakable. One piece I recall from my formative years was Rituel. I saw the American premiere at Tanglewood and it stimulated much of my interest in rhythm which is a dominant feature in my music.

TM: Let’s move from Montreal to Philadelphia. Who was your primary teacher at Penn?

JR: I worked primarily with Richard Wernick who is a remarkable and eloquent composer and tremendously inspiring teacher. His extraordinary recent String Quartet No. 7 contains a 10-minute mensuration canon that is truly virtuosic and is of especial interest to me because of its rhythmic aspects. I also worked with George Crumb, who is of course a living legend — an incredible composer and a wonderful person — warm, witty, highly supportive and knowledgeable about many off-the-beaten-track kinds of things. I am the president emeritus of Orchestra 2001, a Philadelphia based ensemble specializing in contemporary music. George has composed a number of pieces for the group, most recently his extraordinary American Songbooks based on American folk tunes. I also studied harmony with George Rochberg — I never studied composition with him, unfortunately. The timing never worked out. His was one of the great musical minds I have encountered. These three composers wrote very different kinds of music. George Rochberg had just turned to writing a very traditional kind of tonal music about which I subsequently wrote an article for Perspectives of New Music2. But as different as they were they seemed to share something, in the sense that if you compared them to anybody else who was writing, they had more in common philosophically than just about any other composers you could put together. For example, George Crumb’s music is primarily tonally based but not in the same way as George Rochberg’s. All three were absolutely fantastic teachers, again very different from one another with each offering his own special musical vision based on supreme knowledge of the literature and superb technical mastery.

Also I have to say I have undoubtedly learned more about music from exchanging ideas with my many wonderful students over the last 35 years than any other single source.

TM: How would you have described your own style when you moved from Montreal to Philadelphia?

JR: I was studying all the great composers from the first half of the 20th century — especially Berg — and all the contemporary music I could get my hands on. The first half of the twentieth century is like a mini-century in itself, with an incredible roster of composers — there must be twenty-five from that period who are in the standard repertoire today. I was trying to write music that had the searing qualities and expressive qualities of serialism but could still evoke the wonderful moods of warmth and nobility that tonality brought.

TM: Could you say something about what it is that produces an “American” voice for composers? Is this something that is important?

JR: That’s a tricky issue, since this country exists as it is because of many immigrations and cultural importations. There were and are so many influences in this country — our American culture has been seeded by the heritages of the world and the result is something like a multi-colored mosaic. It’s interesting that in the second half of the 20th century America reversed the trend and is undoubtedly the leading exporter of culture.

I tend to divide the music of this country into two categories: music that has been influenced by European music and music has not been (or has been minimally). Jazz certainly fits that non-European bill. George Gershwin is the perfect hybrid of the two categories — he absorbed jazz and Gullah elements into his style as Bartok assimilated Eastern European folk music. American serial music on the other hand never sounds to me very American — even Copland’s Inscape, which sounds very Copland, does not come across as necessarily American. To me the most quintessentially American piece is Ives’ Concord Sonata, especially the introverted last movement “Thoreau”. Even the quotation of the Beethoven Fifth Symphony comes across like an imitation or memory of the Beethoven the ancestral European. Ives delves deeply and convincingly into our historic, literary and musical pasts as well as employing the most modernistic techniques. But of course he too had strong European academic musical credentials through his study with Horatio Parker who in turn had been trained in Munich.

My own music is more Western than particularly American or global. When I say I am influenced by jazz or Indian music, I don’t mean that I have swinging saxophone solos or improvisations in the manner of Charlie Parker or tabla solos like Zakir Hussain’s. Rather I am influenced by the management of the technical elements — the theory if you will — on which these musics are founded and generated. I utilize elements of their systems but my music remains clearly of the Western classical tradition. This incorporation of the techniques of other classical musical traditions is for me the most productive kind of “fusion”. What do I mean by “classical”? Not necessarily Western classical music, though obviously it’s one of those major traditions — but rather any music that has developed around a praxis whether it’s tala, blues, Western harmony, modal counterpoint or raga.

TM: Carnatic music, even more so than north Indian music, seems to be little-known to American listeners. What was your path into this music?

JR: It has often been remarked that of the parameters in Western music, rhythm seems to be the one that is least studied. I would suggest that that’s because rhythm is the least codified. There is little in the way of a particular method for Western rhythm as there is for harmony and counterpoint, except perhaps for Paul Creston’s Principles of Rhythm. Western rhythm seemed to be dependent on elements of harmony and voice-leading, especially in tonal music. I was always very interested in trying to discover a rhythmic method that was as powerful and flexible as that of tonal harmony. Messiaen did a lot of work with rhythm, so I studied Messiaen’s own rhythms and the Indian sources that inspired him so powerfully. I was fortunate enough to be invited to study at Tanglewood in 1975 when Messiaen was there — the first summer that he had been there in twenty-five years. He was actually writing his treatise on rhythm at the time, which I was very excited to see — it was left unpublished at his passing, and came out a few years ago. He was probably the first composer I encountered who showed me that musical riches were to be found in other classical traditions.

I had long been very interested in rhythm and had amassed many file folders, read books on African rhythm, studied the 120 deśītālas of Śārṅgadeva (one of Messiaen’s sources) — all of that kind of thing. But I always felt that my use of these materials was limited. If I found a particularly interesting African rhythm in, say, three layers, putting an oboe, bassoon and clarinet on each part wasn’t really using the rhythm — it was rather a kind of cut and paste approach. What I wanted to do find a way to “work” rhythms in the same way that you could develop a melody or modulate.

Then in the early 1990s, I was fortunate enough to meet Adrian L’Armand, an Australian violinist who specialized in Carnatic music. I was living in Swarthmore Pennsylvania at the time, and he lived around the block from me. How fortunate is that?! We were discussing Berio’s Circles one day and then he started talking about rhythm. In less than a minute I realized that he knew more about rhythm than anyone I had ever met. He talked about rhythmic displacement, variation and development — the very things that I was looking for. I immediately began to study rhythm with him, and continued for several years. It’s interesting how things quickly opened up compositionally for me.

In Western music, the cadence is implied by the unfolding harmony and voice leading. The basic gist of this rhythmic approach is that at least two layers of rhythmic motives (often based on 5's and 7's) are developed within a phrase. By making their total individual values equal (ie 7 groups of 5 = 5 groups of 7) the unfolding of the phrase will be such that the cadence point is implied by the rhythms alone. I call this technique “rhythmic polyphony”. Superimposing other regular and irregular rhythms (such as bembé and the like) leads to still more interesting and complex results. Traditional Baroque devices like augmentation and diminution produce wonderful effects, especially in tuplets. All this gave my counterpoint greater depth. Also, unlike Indian music in which a tala is used for a whole piece or at least a major portion, I change talas and rhythmic groups often, from whole sections to single measures. I think of this approach to rhythm as being somewhat analogous to Western harmonic rhythm where the rate of chord-change varies within the phrase.

TM: What is the source or sources of your pitch material?

JR: I am often asked that. I use an approach I think of as “chromatic modality”. This involves the full vocabulary of traditional scales and modes in which notes outside the set (non-diatonic tones) are introduced and are either subsumed by the diatonicism surrounding them, or “resolved” into the diatonic set. (Like my rhythmic procedures, a given set of pitches can be quite prolonged or shift quickly by phrase, by measure or even by chord.) I think this may be similar to Ives’ strategy in the Concord and some of the songs. Scriabin certainly used chromaticism in octatonic and whole tone contexts as I point out in my article. Debussy’s style may also have some similarities. It is characterized by a mixture of pentatonic, whole tone and modal scales tempered with a highly effective but unpredictable dose of Wagnerian chromaticism.

TM: What are some pieces in which these elements are particularly important in generating the musical fabric?

JR: Any of my pieces written after 1990 — after I had written Rasputin and my three symphonies. The first major work was Rhythmic Garlands, a piano piece that I wrote for and has been recorded by Jerome Lowenthal. That was followed by Duo Rhythmikosmos for violin and piano, a piano trio entitled Trio Rhythmikosmos, and Yellowstone. I also used these techniques in other major pieces — the choreographic tone poem The Selfish Giant based on Oscar Wilde’s fairy tale, Satori for voice and piano (also in several ensemble arrangements), the string quartet Memory Refrain, Across the Horizons for clarinet, violin cello and piano, Concerto for Horn and 7 Instruments, and the violin concerto The River Within among others. My website as well as the webpage at my publisher, Theodore Presser, contain full listings.

TM: Please talk about your opera Rasputin, which was premiered in New York in 1988, with a recent performance in Russia. Were there some revisions for the more recent performance?

JR: The genesis of Rasputin began when I taught at my alma mater, Hamilton College in upstate New York in the 70’s. Christopher Keene was the artistic director of the Syracuse Symphony and premiered my Second Symphony in 1980 which I wrote with the support of a Guggenheim. Keene later conducted the piece with the Philadelphia Orchestra as well as my Third Symphony with the Long Island Philharmonic.

In the mid-80s, Keene introduced me to Beverly Sills who was the Executive Director of the New York City Opera and Rasputin was commissioned. Frank Corsaro was the stage director. My longtime interest in theater and ensuing close relationship with Frank — a tremendously imaginative and stimulating colleague — prompted me to write the libretto. The wonderful bass-baritone John Cheek sang the title role.

The Helikon production premiered in 2008-09 and was included in the “Helikon Opera of the Twentieth Century” retrospective series in April 2010. This production contains some revisions and a few cuts that I think makes the opera more effective dramatically. Lenin was moved exclusively to the end, for example.

My association with Helikon began when I met the artistic director and founder of the company, Dmitry Bertman, in 1994 on my first trip to Russia. Bertman was just starting the company and had only two or three people working for him. He wanted to produce Rasputin right away and actually scheduled it for 1996 but eventually didn’t have the forces or the finances to put it together at that time.

I am very excited about the Helikon production and think it has everything a composer could hope for. The cast, chorus, musicians, set and costume designers are superb. Bertman is a brilliant director with a vision that is vibrant and original but always within the boundaries of the material as I have conceived it. He brings out every element of turbulence and lyricism in the opera. Bertman captures the spirit and timing of both my music and libretto and infuses it with many bold gestures as well as thousands of wonderful details. The set consisted of gigantic Fabergé eggs nestled in egg crates highlighting the contrast between the exquisite world of the aristocracy and the rough-hewn lives of the working class that overthrew it in 1918. The topic of Rasputin and the murder of the royal family is still widely discussed in Russia. There was a court ruling on it even as the premiere of the opera was happening — the killing was judged to be a political act and the Tsar's family were considered to be victims of Bolshevism. Of course Nicholas, Alexandra and their children were canonized about 30 years ago. There was also a recent campaign by a religious faction to canonize Rasputin and Ivan the Terrible. It failed.

Opera Massy in Paris has scheduled Rasputin for November-December 2010 utilizing the Helikon production.

TM: Will there be a CD or DVD from the production?

JR: I am working on making a commercial DVD. We have a filming company in Moscow ready to go and are now seeking financing and a distributor for the US and Europe. Excerpts of the Helikon production (recorded in-house) can be seen online here.

TM: Do you have plans for future stage works?

JR: I am currently working on an opera based on Strindberg’s play The Ghost Sonata, which is a work I have loved since I was in high school. I remember an extraordinary performance of it on television in the ‘60s with Robert Helpmann and Jeremy Brett — and have sought a video recording in vain. I started working on the opera about six months ago and have written about a third of it. Also, though The Selfish Giant was given a wonderful premiere performance by the Philharmonia Orchestra under Djong Victorin Yu and has been performed in the States, it has never been choreographed. So I am also pursuing that.

TM: Will The Ghost Sonata be a full-length evening?

JR: Yes — it’s in three scenes, each about forty minutes.

TM: What is about this play that grabs you?

JR: It’s a very mystical, frightful, zany and yet poetic play — a strange mix, and yet everything works. It has all of the elements of opera — drama, other worldliness, striking characters. Every opera has some sort of other-worldly facet about it which is what its music deals with. The music is in an imaginary domain which gives the characters a means to express their inner sensibilities beyond words. They are unaware that they are singing unless it’s a specific song in the opera such as Walther’s Prize Song. On the psycho-dramatic side, Strindberg’s play is about people who gleefully reveal the fatal inner weaknesses of their opponents and in so doing expose their own. And of course there’s a love story, and a very unusual one at that. The play inhabits what I think of as a world of realistic fantasy. Most of the actions are normal and the setting is middle class. But with the creation of bizarre elements such as a ghost of the Milkmaid and a “mummy” in the closet, Strindberg creates a mood of penetrating psychological dread. The setting and general tone of the dialogue are like Chekhov or Ibsen but by the end we are not sure what plane of reality we are on. And at the last moment a coup de théâtre occurs as the scene disappears completely, rather like Exit the King….

TM: I was interested to hear Howard Shore describe his music for The Lord of the Rings as his only chance to write a Wagnerian opera.

JR: To compose in the epic manner must be a wonderful challenge.

TM: Perhaps you might talk about your piano music.

JR: I mentioned Rhythmic Garlands, my first extended piano work. Before Garlands I had written very little piano music though I am an ardent pianophile. I learned much about counterpoint listening to how pianists like Horowitz brought out inner voices. But I had not composed an extended piano piece before I studied rhythm closely. Studying the piano music of Nicholas Medtner was also a revelation. Medtner, who died in 1951, seems to me the most rhythmically sophisticated of the completely tonal composers.

After Rhythmic Garlands I wrote Sonata Rhythmikosmos which was commissioned by Mari Akagi, a wonderful Japanese pianist who premiered it in Tokyo when I was on a US-Japan Creative Arts Fellowship. That was followed by the violin Duo and Yellowstone Rhythms for bassoon and piano, both of which have extended piano parts. Yellowstone is a 15-minute lyrical rhapsody with bubbly and energetic contrasts. The Six Pictures from the Devil in the Flesh piano suite came from another opera project, one that eventually did not materialize. In the late ‘90s I was contacted by Vincent Malle, the brother of the late film director Louis Malle, about the possibility of writing an opera-film based on the novel Le Diable au Corps by Raymond Radiguet. I worked on this with Gude Lavitz, a wonderful film director who had made a documentary on the student uprisings and strikes in Paris in the 1960s. The project didn’t get the financing it needed so never came to fruition, but I composed some pilot music which I used in my Concerto for Cello and 13 Instruments (which has been recorded by Ulrich Boeckheler and Orchestra 2001 on CRI) and the Six Pictures. Each picture is a mood piece. I thought of them like the Debussy Preludes, each of which evokes a suggestive expressive atmosphere. So even though the opera project didn’t materialize, there were many good things that resulted from it. Marc-André Hamelin made a splendid recording of the Six Pictures as well as Yellowstone with bassoonist Charles Ullery.

TM: Hamelin is an astounding pianist.

JR: Yes, he really is — just incredible. He also recorded Sonata Rhythmikosmos and played the piano part in the premiere of my piano quintet Powers That Be with the Cassatt Quartet. Working with him is a wonderful experience — he is so often able to go beyond what you think is the limit of what can be done, especially in terms of clarity, detail and concentration of effects. His highly expressive delicacy is superb as well.

TM: Could you talk about future projects that you may have coming up? There’s the opera, of course.

JR: I don’t have a production yet for The Ghost Sonata, and I must admit have been somewhat slow to pursue that matter because as soon as I do I will be facing a deadline. I am enjoying composing this piece on my own time. Exciting as it was to compose Rasputin, I had to write the whole opera including the libretto in two years as well as teach. Sometimes you want to linger a little more than a deadline will permit. But I will begin to seek a production for The Ghost Sonata this year.

On the instrumental front, my new piece Lunahuaná for two percussionists will receive its premiere this coming fall.

TM: with a Latin American connection?

JR: Yes — my wife, Cecilia Paredes, is a visual artist from Perú. We spend summers and the winter holidays there. Lunahuaná is a town about sixty miles south of Lima, in a very unusual location where the cloud cover that continually hovers over the greater Lima area abruptly stops. I mean very abruptly — you can see the blue sky seemingly buttressed up against a wall of clouds. My piece evokes the atmosphere of the town, from its haunted history to a fiesta with fireworks and whistles.

I am now working on several new pieces: a rhapsody for violin and orchestra for Maria Bachmann who premiered my violin concerto The River Within; an extended piano piece for Konstantinos Papadakis; and a new version of The Selfish Giant for narrator and chamber orchestra.

1 Reise, Jay “Late Skriabin: Some Principles Behind the Style,” 19th Century Music, Sp.1983, pp. 220-231; reprinted in The Journal of the Scriabin Society of America, Winter 1996-97 pp. 29-46

2 Reise, Jay “Rochberg the Progressive”, Perspectives of New Music, 1980-81, pp. 395-407

image=http://www.operatoday.com/reise.png image_description=Jay Reise [Photo by Cecilia Paredes] product=yes product_title=Jay Reise: An Interview by Tom Moore product_by=Above: Jay Reise [Photo by Cecilia Paredes]Die Walküre in San Francisco

Whispers about the price tag of the upcoming Met Ring suggest the proportions of a foreign war.

Gratefully as well the SFO Rheingold and Walküre have looked like opera, and not like crazed imitations of Star Wars, so they are easier to talk about. Though not necessarily a more or less compelling take on Wagner’s mega opera, this plain SFO Ring is unfolding as conceptually direct and wonderfully human.

Two years ago Rheingold got the San Francisco Ring off to a rocky start with its light weight cast and unfocused staging. Still it was a promising beginning with lots of ideas, some of which did not work all that well (the Nibelheim special effects as example). But lots of fun came out of its director Francesca Zambello who imposed a light touch on the divine machinations that initiate this long saga of greed and love, affectionately capturing the naivete, optimism and entrepreneurial fun that built our cities.

Conductor Donald Runnicles got right to the point in Walküre, not even allowing the applause that greeted him to die before attacking the complications motivated by Wotan’s insecurities. The War Memorial Opera House is particularly kind to Wagner, allowing the transparency within his massive orchestral sound to project the depth of his mountainous landscapes, and as well the myriad of musical motivations to coexist amongst themselves and within this cosmic nature. Mo. Runnicles exploited the Walküre score to its utmost, a remarkably rich reading.

Eva-Maria Westbroek as Sieglinde, Raymond Aceto as Hunding and Christopher Ventris as Siegmund

Eva-Maria Westbroek as Sieglinde, Raymond Aceto as Hunding and Christopher Ventris as Siegmund

Die Walküre is no place for lightweights (as in fact Rheingold is not either), and San Francisco Opera rose to the occasion with a nearly stellar cast. The Siegmund of English tenor Christopher Ventris captured the youth of a young hero, his voice beating with energy, the Sieglinde of Dutch soprano Eva-Maria Westbroek soared vocally over the maelstrom with the unborn hero in her womb. But it was Swedish sopranto Nina Stemme’s Brünnhilde whose voice rose over all else as the energy and psychic spirit of Wotan, her creator and the world’s master builder.

This is an American Ring (the mountains are surely our California Sierras, though there is no defining land or river-scape). Hunding’s cabin is an American primitive wood facade with a screen door that can be found no where else in the world other than in middle America. American bass Raymond Aceto in a long sleeved winter undershirt with suspenders was a medium voiced Hunding, his strut and menace hiding this character’s predestined impotence. Paired with his unhappy, beaten and defeated wife, Sieglinde in a ill fitting, sad pale blue dress Hunding, strangely, evoked sympathy.

Costumer Catherine Zuber dressed German mezzo Janina Baechle as Wotan’s wife Fricka in a sort of purple beaux arts long gown in which she stolidly prevailed as a wet-blanket moral conscience. Meanwhile Wotan, American bass Mark Delavan from the Rheingold cast, muttered and spat effectively as some sort of railroad tycoon, but was vocally pallid even before running out of voice (June 22).

Wendy Bryn Harmer as Gerhilde, Suzanne Hendrix as Schwerleite, Tamara Wapinsky as Helmwige, Pamela Dillard as Grimgerde, Daveda Karanas as Waltraute, Maya Lahyani as Siegrune, Priti Gandhi as Rossweise and Molly Fillmore as Ortlinde

Wendy Bryn Harmer as Gerhilde, Suzanne Hendrix as Schwerleite, Tamara Wapinsky as Helmwige, Pamela Dillard as Grimgerde, Daveda Karanas as Waltraute, Maya Lahyani as Siegrune, Priti Gandhi as Rossweise and Molly Fillmore as Ortlinde

Wotan’s Valhalla is seen through the window of a massive high rise. It was not specifically San Francisco but a high rise city profile that is specifically American, with echoes of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Set design for this American Ring is by Michael Yeargan who, with Mme. Zambello is working in a determined post-modern vocabulary, Wotan’s desk a huge table with four huge wooden claws as legs, the following scene moving onto the contemporary detritus under an abandoned elevated freeway, and finally an abstract space for the Valkyries and the Wotan farewell to Brünnhilde.

Beautiful, detailed lighting by Mark McCullough subtly caught a real life wolf-dog and his cub racing across the stage as Wotan was about to kill his son, connecting the innocence of real nature to the tragedies of cosmic destiny. McCullough magically captured the steel gray folds of Wotan’s coat covering the sleeping Brünnhilde as a ring of real fire began to encircle the stage, this real fire somehow making the fairytale ending of the Ring’s second installment humanly real, and unusually moving.

Everything in this Ring was ordinary, and that was its triumph. Rarely has operatic acting achieved this level of realism delicately sitting on the verge of expressionism. This accomplishment signals heroic efforts of stage direction plus determined commitment from singers. Miraculously this staging melted effortlessly into the Runnicles reading of the score, the abstract musical motivations from the pit rendered on the stage in movement that effortlessly and truly portrayed complex dramatic motivations. Gesamtkunstwerk indeed!

It was a good night at San Francisco Opera.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/_MG_8852.gif

image_description=Mark Delavan (Wotan) and Nina Stemme (Brünnhilde) [Photo by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Richard Wagner: Die Walküre

product_by=Brünnhilde: Nina Stemme; Wotan: Mark Delavan; Sieglinde: Eva-Maria Westbroek; Siegmund: Christopher Ventris; Fricka: Janina Baechle; Hunding: Raymond Aceto; Ortlinde: Molly Fillmore; Schwertleite: Suzanne Hendrix; Waltraute: Daveda Karanas; Gerhilde: Wendy Bryn Harmer; Helmwige: Tamara Wapinsky; Siegrune: Maya Lahyani; Grimgerde: Pamela Dillard; Rossweise: Priti Gandhi. Conductor: Donald Runnicles. Director: Francesca Zambello. Set Designer: Michael Yeargan. Costume Designer: Catherine Zuber. Lighting Designer: Mark McCullough. Projection Designer: Jan Hartley. Choreographer: Lawrence Pech.

product_id=Above: Mark Delavan as Wotan and Nina Stemme as Brünnhilde

All photos by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

June 27, 2010

Massenet's Thaïs at Teatro Regio Torino

A good place to evaluate one's answer to that question comes in the form of this DVD of Stefano Poda's staging of Thaïs by Jules Massenet (composer) and Louis Gallet (libretto). Viewers who find the opera slightly risible but who still enjoy the music are likely to be amused and fascinated by Poda's over-the-top aesthetic, part dance and performance art spectacle, part out-of-control fashion runway show. Anyone actually captivated by the opera's conjunction of overripe sexuality and pained religiosity may be much less pleased.

A fairly long opera for its story, Thaïs has a cast listing of 9 roles, but the story never strays far from the title character and her admirer, a monk who sets out to convert the courtesan from her sinful ways and put her on the path to righteousness. In the end, the monk Athanaël finds himself over come by her attractions, but it is too late for his own conversion to sensuality, as Thaïs can no longer respond, having forsaken her former life and then, after being born again, rather abruptly dying.

The Metropolitan Opera recently staged Thaïs with stars Renee Fleming and Thomas Hampson in the leading roles, and stars of that magnitude are needed. Without their charisma, a flimsy story and the fallows of the score between its 2 or 3 highlights make for a forgettable evening. Excellent singers both, such charisma doesn't get projected by Barbara Frittoli or Lado Ataneli, caught on this recording in live performance from 2008 at the Teatro Regio Torino. Frittoli has beauty enough for the role, edging just a bit into Rubenesque territory. Only in her big scene, the so-called Mirror aria, does the relative blandness of her vocal instrument come into too close focus. Ataneli, no actor, doesn't do much more than glower and look down, and in his dark floor-length tunic he looks a bit like Rasputin on a Middle East holiday. His handsome voice, however, makes credible the growing attraction the courtesan feels for him. In the only other truly notable role, as Thaïs's Babylonian sugar daddy Nicias, Alessandro Liberatore doesn't so much disappear into the role as just disappear.

What makes this show a fascinating experience is the total design effort of director Stefano Poda, who also choreographs and designs the sets, costumes, and lighting. He has no interest in pretending this is a naturalistic story of early AD Babylon. He plays with black, mostly in the costumes, and white in the sets. He does not attempt much differentiation between the libretto's settings, opting instead for a stylized dimension where barely clothed dancers sweep on and off, illustrating the action in the opera's extensive instrumental passages. It all borders on the silly, but so does the opera. Poda's flow of invention in creating eye-catching stage pictures makes the show not just bearable but actually fairly entertaining, especially seen in the incredibly crisp and detailed Blu-Ray picture.

Gianandrea Noseda elicits sensuous playing from the house orchestra. The production in the Metropolitan Opera's performances, broadcast last year in the HD Moviecast series, was also fairly stylized, but it didn't draw attention to itself the way Poda's does. If that sounds like criticism of this version, stay away. If it sounds appealing, check it out.

Chris Mullins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ArtHaus101386.gif

image_description=Jules Massenet: Thaïs

product=yes

product_title=Jules Massenet: Thaïs

product_by=Thaïs: Barbara Frittoli; Athanaël: Lado Ataneli; Nicias: Alessandro Liberatore; Palémon: Maurizio Lo Piccolo; Albine: Nadežda Serdyuk; Crobyle: Eleonora Buratto; Myrtale: Kete van Kemoklidze; La Charmeuse: Daniela Schillaci; Un serviteur: Diego Matamoros. Torino Teatro Regio Chorus (chorus master: Roberto Gabbiani). Torino Teatro Regio Orchestra. Gianandrea Noseda, conductor. Stefano Poda, stage director, choreographer, set, costume and light designer. Recorded live from the Teatro Regio Torino, 2008.

product_id=ArtHaus 101386 [Blu-Ray DVD]

price=$35.39

product_url=http://astore.amazon.com/operatoday-20/detail/B002ED6UY6

June 26, 2010

Is anybody listening? American opera faces crossroads as audiences for performing arts slide

By Anne Midgette [Washington Post, 27 June 2010]

When "Moby-Dick," a new opera by Jake Heggie, was announced as part of the Dallas Opera's season in its brand-new Winspear Opera House, there was skepticism in the opera world. How was this long, discursive novel going to make it to the stage in any form that would get people to want to listen to it? It became a standard joke to ask which large singer would play the whale.

June 24, 2010

Opera Orchestra of New York Stages a Comeback

By Daniel J. Wakin [NY Times, 24 June 2010]

The Opera Orchestra of New York, a small but beloved institution for fans of off-beat repertory and big voices, is staging something of a comeback. The company said Thursday it would end its financially induced hiatus and mount two concert productions next season: Meyerbeer’s “L’Africaine,”and a double bill of Massenet’s “La Navarraise” and Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana.”

June 23, 2010

Three iconic places to see an opera in Italy

By Giovanna Dell'Orto [The Associated Press, 23 June 2010]

MILAN, Italy — Opera is as fundamental to Italy's soul as the Colosseum, Michelangelo or pasta. To attend an opera performance here in the summer is a quintessential Italian experience — especially if you're willing to brave the often-byzantine process for getting last-minute but astonishingly cheap tickets.

San Francisco's feminist 'Die Walkure'

By Mark Swed [LA Times, 23 June 2010]

Walkure Late Saturday night, Valhalla will fall for the final time in Los Angeles, and the Music Center will send its expensive “Ring” into long (possibly permanent) storage. And that will be that.

Leipzig Opera to stage Gluck Ring

It was thus hardly a surprise when Leipzig Opera approached its chief resident director Peter Konwitschny and suggested that he consider staging the Ring to celebrate the anniversary. Konwitschny, son of the late music director of Leipzig’s esteemed Gewandhaus Orchestra and among the most erudite and experienced of today’s German directors, pointed out that the Big Birthday will prompt a rush of Ring stagings throughout Germany and suggested that Leipzig consider rather new productions of four operas by Christoph Willibald Gluck, the man who late in the 18th century rescued opera from the excesses of the Baroque spectacle that it had become. Wisely, the Leipzig Opera knew a good idea when they heard one and told Konwitschny to go to work.

The director launched the project earlier this season with a new production of Alceste — or Alkestis, as it is known in Germany, which was seen at the last performance of the current season in Leipzig’s 50-year-old, 1260-seat opera house on June 18. Stagings of Gluck’s two Iphigenia operas — in Aulis and Tauris — and of Armida will follow. Konwitschny defines the common ground that will give coherence to the cycle as studies of four unusually strong women viewed from a perspective that reaches from the beginning of time to the present day. All four are dramas, he says, in which the conflict between love and power is of central importance. Konwitschny points out that the later masters of music theater — Mozart, Wagner and Richard Strauss — were all Gluck fans. Indeed, Wagner conducted Gluck and wrote about his work in his own essay Opera and Drama.

Konwitschny is a long established master of Regieoper, the practice widely spread in Germany — and now in other countries as well — of giving a director a totally free hand with a work, even if the original story is hardly recognizable in the resulting staging. What sets Konwitschny apart from other directors, however, is his regard for the composer and the story that he once told. He is there to respect — and serve — history. Yet nothing would have prepared a foreigner uninitiated in Regieoper for what Konwitschny has done with Alceste.

In his own new and original score for the opera he concludes the 1767 Vienna version with the satyr play that Gluck wrote for the Paris production of the opera nine years later. Konwitschny plays the first two acts “straight” — indeed in the majesty of their extended choruses there are markings of the sublime that one once dared expect from great art. Greek soprano Chiara Angella — a fitting choice for the heroine — sings her demonic address to the gods of the underworld with true dramatic pathos against the leaden skies projected on the rear wall of the simply-set stage. Then — with no hint of the change to come — the curtain opens Act Three in Her-Cool-TV, a television studio, in which a curly blond-wigged body builder Hercules is the host.

The chorus discards its togas in favor of jeans, colored shirts and baseball caps and sits in bleachers on either side of the stage. The studio crew feeds them their lines on posters and tells them when to laugh. The mayhem that ensues stresses the degree to which TV has corrupted modern life — and been corrupted by it. Alceste and Admetos — Belgian countertenor Yves Saelens — progressively lose ground as they argue about which of them has the greater right to die first. Finally, Apollo — dressed in the business suit of a successful politician — brings things to a happy end from the elevated loge where East-German leaders once sat at the Leipzig Opera. As the curtain falls, the reunited couple is wrapped in Saran Wrap.

Soula Parassidis as Alceste [Photo by Andreas Birkigt courtesy of Oper Leipzig]

Soula Parassidis as Alceste [Photo by Andreas Birkigt courtesy of Oper Leipzig]

But, one must ask, where does this leave the audience, which has had an experience of riotous entertainment that few would think available in an opera house? Does one think of the dreadful turmoil Alceste has been through, when even the husband for whom she wishes to sacrifice herself questions her motives? Has Konwitschny given his audience too much of a good thing?

Despite the popularity that Baroque opera has come to enjoy, one would hardly expect a company anywhere to perform two tellings of the Alceste story on successive June evenings. That, however, is what Leipzig Opera did in offering Handel’s Admeto on June 17. (In 1745 Gluck and Handel actually met in London, where they staged a concert together. When director Tobias Kratzer took his first look at Admeto he was overwhelmed by its proximity in spirit to soap opera, which became his model for this staging.

Set in a palace that is already a museum while still serving as a royal residence, Kratzer makes the work a spoof on Europe’s surviving blue-bloods. As Alceste, for example, mezzo Soula Parassidis could be either Grace Kelly or Princess Di. Sleuthing Orindo, superbly played by Kathrin Göring, is an obvious take-off on Miss Marple. The progress that opera made in the years between Admeto and Alceste roughly equals the distance between the Model T Ford and space flights. Katzer understood, however, how to make the Handel superb entertainment. He diverted attention from the static quality of Handel’s da capo arias. He added a stately five-man ensemble that roamed the lobby before curtain time and then participated in on-stage action as players of the melodica, the blow organ introduced by Hohner in the 1960s. In one case, the quintet even accompanied an aria.

Yet it was the quality of the cast and the exemplary playing of the pit ensemble that made this Admeto memorable. (The Gewandhaus Orchestra plays for Leipzig Opera.) Alceste, the most complex character in the drama, was sung by mezzo Soula Parassidis, a coloratura of impressive agility, who touchingly followed the figure through changing modes of loss, sorrow, fury and the desire for revenge. Hagen Matzeit — Admeto — is a male alto who sings with incredible ease, as does male countertenor Norman Reinhardt, who was engaging as the king’s brother Trasimede. And petite Elena Tokar made Antigona sympathetic — despite her confusion of feelings. The cast sang the German translation by Bettina Bartz and Werner Hintze as easily as if it had been the original Italian libretto. Both operas added special flavor to the Leipzig Bach Festival that dominated the one-time home of Bach when these performances were on stage. Major curiosity of the BachFest season was the performance of Johann David Heinchen’s Die Lybische Talestris, possibly the first opera performed in Leipzig over 300 years ago. Sigrid T’Hooft, who reconstructed the score from material in Berlin’s Singakademie directed students of Leipzig’s Hochschule für Musik und Theater in the production staged in the tiny Bad Lauchstädt theater, once directed by Goethe. Alas, the five-hour — and somewhat slipshod — performance on the bare-board seats of the tiny Bad Lauchstädt proved more Baroque than most had bargained for. The theater was largely empty when — long after midnight — the curtain fell. (Allegedly, Heinrich — 1683-1729 — was well acquainted with Bach.) One rarely hears of anyone who has gone to Leipzig for opera. It is clearly time that one does! Wes Blomster image=http://www.operatoday.com/OPER-LEIPZIG_3974_Alkestis-.gif product=yes Scene from Die Lybische Talestris [Photo by Gert Mothes courtesy of Oper Leipzig

Scene from Die Lybische Talestris [Photo by Gert Mothes courtesy of Oper Leipzig

image_description=Chiara Angella as Alkestis and Yves Saelens as Admetos [Photo by Andreas Birkigt courtesy of Oper Leipzig]

product_title=Christoph Willibald Ritter von Gluck: Alkestis. G. F. Handel: Admeto. Johann David Heinchen: Die Lybische Talestris.

product_by=Alkestis — Alkestis: Chiara Angella; Admetos: Yves Saelens; Evandros: Norman Reinhardt; Ismene: Viktorija Kaminskaite; Herkules: Ryan McKinny; Apollo; Tomas Möwes. Conductor: George Petrou; Director: Peter Konwitschny; Sets:Jörg Kosdorff; Costumes: Michaela Mayer-Michnay; Video: fettFilm

Admeto — Admeto: Hagen Matzeit; Alceste: Soula Parassidis; Herkules: Miklo’s Sebestye’n; Orindo: Kathrin Göring; Antigona: Elena Tokar. Conductor: Federico Maria Sardelli; Director; Tobias Katzer; Sets/costumes: Rainer Sellmaier; Lighting: Michael Röger

Die Lybische Talestris — Pelopidus: Dominik Grosse; Philotas: Julia Kirchner; Talestris: Amrei Bauerle; Syringa: Christiane Wiese. Conductor: Suzanne Scholz; Director: Sigrid T’Hooft; Costumes: Stephan Dietrich. Staged by students from the Leipzig Conservatory for Music and Theater.

product_id=Above: Chiara Angella as Alkestis and Yves Saelens as Admetos [Photo by Andreas Birkigt courtesy of Oper Leipzig]

VERDI: Otello — La Scala 1954

First Performance: 5 February 1887, Teatro alla Scala, Milan.

| Principal Roles: | |

| Otello, a Moor, general of the Venetian army | Tenor |

| Iago, an ensign | Baritone |

| Cassio, a platoon leader | Tenor |

| Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman | Tenor |

| Lodovico, an ambassador of the Venetian Republic | Bass |

| Montano, Otello’s predecessor as Governor of Cyprus | Bass |

| A Herald | Bass |

| Desdemona, Otello’s wife | Soprano |

| Emilia, Iago’s wife | Mezzo-Soprano |

Setting: A maritime city on the island of Cyprus, at the end of the 15th century

Synopsis:

Act I

Cyprus, near the harbor; an inn nearby, the castle in the background

It is night and a storm is raging. The people of the island are looking out to sea, anxious for Otello’s ship. It arrives safely and he greets the crowd with a shout of triumph: the storm which has spared him has completed the destruction of the Turkish fleet begun by him. Frustrated in his love of Desdemona, Roderigo is ready to drown himself, but Iago counsels him to be sensible. He hates Otello for having appointed Cassio captain over his head and will help Roderigo and have his own revenge at the same time.

As the islanders celebrate, Iago invites Cassio to drink the health of Otello and Desdemona, knowing that he has no head for liquor. Prompted by Iago, Roderigo begins a quarrel with the intoxicated Cassio, and when Montano tries to stop them, Cassio attacks him. Iago urges Roderigo to rouse the town.

Otello interrupts the fight and, discovering that Montano is wounded and angry because Desdemona’s sleep has been disturbed, demotes Cassio. He orders Iago to calm the population. Otello and Desdemona, left alone, remember the days of their courtship.

Act II

A hall in the castle with a garden in the background

Iago suggests to Cassio that he try to regain favor by asking Desdemona to intercede for him and exults in his inborn capacity for evil. He watches as Cassio approaches Desdemona and, noting the arrival of Otello, pretends to be worried about Cassio’s manner, going on to suggest the possibility of a relationship between him and Desdemona. He then warns Otello to beware of jealousy and advises him to observe his wife. After groups of Cypriots have sung a welcome to Desdemona she begins to plead for Cassio, but Otello puts her off, complaining of a headache. When she tries to bind his forehead with a handkerchief, he throws it to the ground, where it is picked up by Emilia.

Desdemona begs her husband to forgive her if she has unconsciously offended him and he broods that she may have ceased to love him because of his color and age. Iago snatches the handkerchief from Emilia, intending to leave it in Cassio’s lodging.

Otello orders Desdemona to leave and Iago continues to undermine Otello’s faith in her. Lamenting that his peace of mind has gone, Otello demands proof of her infidelity, so Iago claims to have overheard Cassio in his sleep betraying his love for her. He also says that he has seen the handkerchief, Otello’s first love-token to Desdemona, in Cassio’s hand. Otello vows vengeance and Iago vows to dedicate himself to this cause.

Othello and Desdemona, by Alexandre-Marie Colin [Source: Wikipedia]

Othello and Desdemona, by Alexandre-Marie Colin [Source: Wikipedia]

Act III

The great hall of the castle

A herald announces the arrival of a galley from Venice. Iago promises to induce Cassio to betray his love for Desdemona in Otello’s hearing.

When Desdemona again tries to speak of Cassio, Otello asks her to bind his forehead with the handkerchief. Becoming agitated when she is unable to produce it, he warns her that its loss will bring misfortune and accuses her of infidelity, driving her away, unmoved by her tears and protestations of innocence.

His grief at this affliction which has been sent to try him turns to rage as Iago gets him to hide while he talks to Cassio — a cunningly contrived conversation partly about Desdemona and partly about the courtesan Bianca, who is madly in love with Cassio. Otello, unable to hear everything, misinterprets Cassio’s amusement, particularly when Cassio produces the handkerchief, expressing puzzlement as to how it appeared in his lodging, and he and Iago laugh.

As trumpets proclaim the arrival of the Venetian ship, Otello resolves to kill Desdemona and Iago promises to take care of Cassio. Everyone gathers to welcome the ambassador. As Otello reads the despatches brought by Lodovico, he hears Desdemona express sympathy for Cassio and strikes her. He announces that he has been recalled to Venice and Cassio appointed in his place. Lodovico tries to make peace between him and Desdemona, but he throws her to the ground. Furious at Cassio’s promotion, Iago incites Roderigo to murder him, as a means of keeping Otello and Desdemona in Cyprus.

Otello orders everyone to leave, cursing Desdemona when she tries to approach him. As he falls to the ground in a fit, Iago gloatingly places his foot on him.

Act IV

Desdemona’s bedroom

As Desdemona prepares for bed, assisted by Emilia, her heart is full of foreboding and she remembers a girl called Barbara, who died of unrequited love, singing “a song of willow.” Bidding Emilia good night, she prays, then goes to bed.

Otello enters, wakes her with a kiss and tells her to pray for forgiveness for any unabsolved sins. She begs for her life, denying his accusations of infidelity with Cassio. He strangles her. Emila brings the news that Cassio has killed Roderigo, but is unharmed. Hearing Desdemona’s dying protestations of innocence, Emilia calls for help. She reveals the truth about the handkerchief and Montano says that Roderigo had revealed what he knew of the plot before dying. Iago flees, refusing to exculpate himself.

Lodovico takes Otello’s sword, but Otello draws a knife and kills himself, kissing Desdemona as he dies.

[Synopsis Source: Opera~Opera]

Click here for the complete libretto.

Click here for the complete text of The Tragedie of Othello, Moore of Venice and related materials.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Othello_Desdemona.gif image_description=Othello and Desdemona in Venice, by Theodore Chasseriau (1819-1856) audio=yes first_audio_name=Giuseppe Verdi: Otello first_audio_link=http://www.operatoday.com/Otello1954.m3u product=yes product_title=Giuseppe Verdi: Otello product_by=Otello: Mario Del Monaco; Jago: Leonard Warren; Cassio: Giuseppe Zampieri; Roderigo: Luciano Della Pergola; Lodovico: Giorgio Tozzi; Montano: Enrico Campi: Un Araldo: Paolo Pedani; Desdemona: Renata Tebaldi; Emilia: Anna Maria Canali. Orchestra e Coro del Teatro alla Scala di Milano. Antonino Votto, conducting. La Scala, Milano, 7 January 1954.June 22, 2010

La fanciulla del West in San Francisco

Over the long evening we got to know this wall’s every nook and cranny in about every color of light imaginable.

Just when you thought San Francisco Opera got its productions from Chicago this one comes from Palermo (Italy) where its stage director, one Lorenzo Mariani, is the artistic director of the Teatro Massimo. The Italianization of San Francisco Opera is amusing. One can even imagine an Italian operatic mafia that promotes only its own when brokering international deals. This could explain and perhaps excuse the otherwise inexplicable and inexcusable.

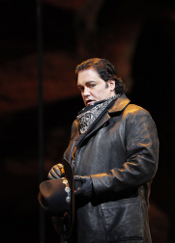

Salvatore Licitra as Dick Johnson

Salvatore Licitra as Dick Johnson

The star of this San Francisco edition of Palermo’s Fanciulla is, no surprise, conductor Nicola Luisotti whose full throated orchestra sang out with delirious abandon Minnie’s true love for the bandito Ramerrez. He pulls us through this evening with orchestral sweep and dramatic point — typical Luisotti.

Mo. Luisotti is indeed a force to be reckoned with. Minnie, soprano Deborah Voight, and Dick Johnson (aka Ramerrez), tenor Salvatore Licitra had no problem at all. Mme. Voight sings her first Minnie, combining a bona fide Americana persona with convincing Italianate singing, cutting loose with high notes as only a dramatic soprano can and here needs to do. Minnie is not the usual Puccini heroine who accepts her unhappy fate. Minnie’s fate is true love that she gains with true soprano coglioni, three aces and a pair, and high notes that simply wither anything that gets in the way!

Salvadore Licitra cuts a fine figure on the stage, the red flag on the back pocket of his Levi’s convincing, the six shooters on his hips menacing . He also sings. His musicianship is impeccable, his phrasing is elegant, and he soars to high notes with ease in his powerful, baritone colored tenor. He should shut up with his retro ideas about opera staging, voiced in an San Francisco Opera Guild preview.

The unhappy, love sick sheriff, Jack Rance, was perfectly rendered by Roberto Frontali who was appropriately emotionally withdrawn though expressive in his brief but revealing soliloquy, and his pleadings to Minnie were touching too. His fine baritone served him just as well when he got mean. Mr. Frontali’s voice, stance and profile would threaten bandits in any spagetti western.

Of the large supporting cast, Timothy Mix [sic] stood out as Sonora, a fine voice and sympathetic, commanding presence, as did young Adler Fellow Maya Lahyani as the Indian Wowkle, the only female voice in the opera other than Mme. Voight.

Salvatore Licitra as Dick Johnson and Roberto Frontali as Jack Rance with Brian Jadge as Joe, Igor Viera as Happy, Timothy Mix as Sonora, Austin Kness as Handsome, David Lomelí as Harry and chorus members

Salvatore Licitra as Dick Johnson and Roberto Frontali as Jack Rance with Brian Jadge as Joe, Igor Viera as Happy, Timothy Mix as Sonora, Austin Kness as Handsome, David Lomelí as Harry and chorus members

Fanciulla is pure Italian kitsch. For Puccini California was a faraway colorful myth. Mix this with his beloved pentatonic scale (in his mind the perfect sound for California as well as Japan) and with a play that is like catchy short story (winning a guy in a card game). So no one expects a production of Fanciulla to be particularly California.

Nevertheless, evidently scene designer Maurizio Balò, like Puccini, has never been to California, because he would know that we do not have funny red brown rocks carved out of foam. Those rocks are in Utah and even there they are not carved out of foam. They turned weirdly blue when it was supposed to be snowing, though the snow was bubbles of some sort rather than flakes. Finally when Minnie and Dick were headed off into the sunset the foam wall turned gold, and split apart revealing a painted drop that was supposed to be, maybe, the Sierras as our plein air artists might imagine them. If this was the idea it failed miserably in execution.

Costumes are credited to American designer Gabriele Berry. The miners’ costumes seemed reasonable in the first act, but in the second act the many men of the posse had all donned identical, sinister, vaguely WWI looking raincoats. For her tryst with Dick Johnson in her cabin Mme. Voight was resplendent in a far too grand Victorian dress that she surely would have shed (but did not) to tease Dick a bit more before she rolled herself up (still in the dress) in a blanket to sleep on the floor (she had given Dick the bed).

Director Lorenzo Mariani moved actors on and off the stage as needed, and platforms holding a bar, a bed and a scaffold as well. When it was time for Minnie to rescue Dick he attempted a coup de théâtre with Minnie arriving on horseback — a bored, placid palomino was led slowly onto the stage by two keepers. Com’on, hasn’t he even seen Zefferelli’s white stallion gallop across the stage to rescue Leonora in Il Trovatore in Verona? That’s theater!

Provincial Italian opera surely has better to offer than this Fanciulla del West.

Michael Milenski

image=http://www.operatoday.com/_MG_4641.png

image_description=Deborah Voigt as Minnie [Photo by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Giacomo Puccini: La fanciulla del West

product_by=Minnie: Deborah Voigt; Dick Johnson: Salvatore Licitra; Jack Rance: Roberto Frontali; Nick: Steven Cole; Sonora: Timothy Mix; Ashby: Kevin Langan; Joe: Brian Jagde; Harry: David Lomelí; Trin: Matthew O’Neill; Handsome: Austin Kness; Sid: Kenneth Overton; Jake Wallace: Trevor Scheunemann; Happy: Igor Vieira; Larkens: Brian Leerhuber; Wowkle: Maya Lahyani; Billy Jackrabbit: Jeremy Milner; Pony Express Rider: Christopher Jackson. Conductor: Nicola Luisotti. Director: Lorenzo Mariani. Set Designer: Maurizio Balò. Costume Designer: Gabriel Berry. Lighting Designer: Duane Schuler.

product_id=Above: Deborah Voigt as Minnie

All photos by Cory Weaver courtesy of San Francisco Opera

A Surreal Russian Opera That's All Bark and a Lot of Bite, Too

By George Loomis [NY Times, 22 June 2010]

AMSTERDAM — When it comes to giving birth to significant new Russian operas, the Netherlands Opera has a better recent track record than any theater in Russia.

Best When It's Tangy, Not Sweet

By Heidi Waleson [WSJ, 22 June 2010]

The beauty of Roald Dahl's darkly comic children's books is how they balance attraction and menace. "The Golden Ticket"—an opera by composer Peter Ash and librettist Donald Sturrock, based on Dahl's novel "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory," having its world premiere at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis—is most successful when its score does the same. The opera's best music is edgy and snappy, its astringent orchestration giving prominence to the winds and the brass, capturing the story's restless unpredictability. But when it ventures into pure lyricism, it often meanders and sags.

Idomeneo at ENO

Idomeneo is a natural product of the courtly world of the Enlightenment — its hierarchies, values and symbols. It should be perfectly possible to translate this tale of vengeful Gods, proud Kings, of the passage from youth to age, and of human sacrifice, to a contemporary setting. Indeed, myth is essentially a presentation of a social worldview which, by delineating the customs and ideals of that society, can reveal how the modern world attained its current form. However, Katie Mitchell’s modern-day production so disregarded the mythic meaning of the work, and discounted the characterisation and motivation of the protagonists, focusing instead on mannered, often manic, stage business, that there was no hope that the audience might empathise with those on stage or relate to the unfolding drama.

The photographic seascape front-drop looked promising. It rose to reveal a clinical latter-day conference centre, the cool beiges and slate greys suggesting the best of contemporary Scandinavian design rather than of sultry climes of Mediterranean Crete. A panoramic window offered a glimpse of a cool, aquamarine ocean, but that’s as close as we got to Poseidon’s stormy seas in this production.

Vicki Mortimer and Alex Eales, Mitchell’s frequent collaborators, may have created a crisp, serene set, but it was immediately transformed into a hot-bed of activity, as waiters, bureaucrats and assorted flunkies charged back and forth, to and fro, in an unexplained and unfathomable flurry of activity. Pity poor Sarah Tynan, who as Ilia is charged with responsibility for clarifying the dramatic situation and mythic context in her opening aria, ‘Padre, germani, addio!’; it was almost impossible to concentrate on her music, words or predicament, so distracting was the surrounding maelstrom — despite Tynan’s serene composure, tender lyricism and excellent diction.

This infuriating fussiness, and the intrusion of countless pen-pushers and attendants, continued throughout the first two Acts, undermining the mythic stature of the work. Thus, while Idamante, seated at the distant end of a twenty-foot dining table, proclaimed his love for Ilia and begged her not to condemn him for the actions of his father (‘Non ho colpa’), Ilia gobbled down her dinner as sommeliers bustled about her, topping up her wine. No wonder she didn’t take him seriously. Iadamante fared little better in his endeavours to woo her in Act 2, as smooching couples intruded on their private moment, swaying distractingly to his words of love.

Mozart’s music sharply delineates the four main characters. Ironically, while over-directing her army of extras, Mitchell left the principals pretty much to their own devices, with mixed results. The composer’s verdict on the original Idomeneo and Idamante (the aging Anton Raaff and the soprano-castrato, Vincenzo dal Prato) was that they were, “the most wretched actors ever to walk the stage”; Mitchell did little to help her actors rise above these lowly standards. While Paul Nilon as Idomeneo was imposing and credible, Robert Murray‘s Idamante was a pretty feeble hero, threatening to slip ineffectually into self-pitying alcoholism. In Act 1 Scene 2, seeking solitude at the base of a cliff, to mourn the supposed loss of his father, Idamante sat unmoving on a craggy boulder, solipsistically bewailing his grief and pain, and failed to recognise the returning king even when he was staring him in the face; the general lack of dramatic credulity made the usual suspension of disbelief even more difficult.

Only Emma Bell, as Electra, injected any real dramatic frisson; unfortunately she was played, admittedly with great panache, as an obsessive neurotic, compulsively stalking the hapless Idamante, cocktail glass clutched firmly in hand — think ‘Sex and the City’ meets the Ugly Sisters. Her Act 2 aria, ‘Idol mil’, where she professes her sincere belief that she might win Idamante’s heart once she has removed him from Ilia’s gaze, was beautifully rhapsodic, a lyric moment of illusory happiness evoking real human emotion and pathos. Mozart’s music provides a moment of genuine compassion, fleetingly humanising Electra. But, Mitchell sees things rather differently: Bell’s hopeful, rapturous arcs became orgasmic swoons, as a civil servant indulged her foot fetishism. Electra’s jealousy should inspire fear, dismay and pity; but here Bell simply became a figure of fun, slumping drunkenly on the sofa, fawning across the indifferent men, her avowals of happiness presented as the deluded idiocies of a drunken clown.

Emma Bell as Electra, Paul Nilon as Idomeno, Robert Murray as Idamante and Sarah Tynan as Ilia

Emma Bell as Electra, Paul Nilon as Idomeno, Robert Murray as Idamante and Sarah Tynan as Ilia

The chorus fared little better. For most of the opera they stood stock still, seemingly bemused as to their role in the drama. They were also musically sluggish and leaden in the opening chorus, ‘Godiam la pace’, although they sharpened up considerably as the opera progressed, and there was some admirable singing from those given small solo roles — Claire Mitcher, Lydia Marchione, Michelle Daly, David Newman and Michael Selby. And, there was one neat visual touch, in Act 2, as the vicious storm breaks before the departure of Idamante and Elektra: rushing from the smart cruise boat departure lounge into the VIP area, to escape from the ensuing tempest (‘Corriamo, fuggiamo’), the huddled crowd presented a fitting visual metaphor for the dread which overcomes them.