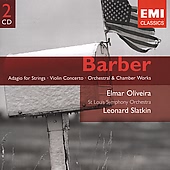

Samuel Barber: Orchestral Works

Elmar Oliveira (violin) and others

St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, Leonard Slatkin (cond.)

EMI Classics 7243 5 86561 2 1 [2CDs]

EMI has re-released a 2-disc set of some of Samuel Barber’s most compelling orchestral and chambers works on the Gemini — The EMI Treasures label. An album of the same recordings was released in 2001, itself a remastering of original recordings dating from the mid-1980s through the mid-1990s. Disc 1 from both these sets contains music recorded in 1986 and 1988 with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leonard Slatkin and released in 1990 as a single disc. The second disc of the set contains chamber music of Barber, recorded in 1995. Each time this music has been released it has received positive reviews. See for example, Jon Yungkans’s review on the The Flying Inkpot; the reviews on Amazon.com; or Victor Carr’s review on Classics Today.

On one hand, EMI’s decision to recycle recordings is frustrating — it would be nice to hear some new performers and different interpretations, or to have access to some of Barber’s less frequently performed works. On the other hand, Slatkin and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra do such a lovely job with this music that the availability of so many affordable options is not to be scorned.

The cover of this most recent release features a small, tattered American flag attached to what can be imagined to be a Midwestern mailbox, rusted and tilted to one side, with tall grass sprouting up from the ground below. The rustic scenery and the American symbolism poses the question, how American is Barber’s music? Or rather, has Barber’s music been perceived as American by critics and listeners?

Barber has long been received as a neo-Romantic, and his sound associated with a more European, post-Straussian sound. Rarely is Barber’s name included in the inventory of American composers that is comprised of such seekers of an American-sounding music as Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Roy Harris, and Leonard Bernstein, among others. Barber’s exclusion from this catalogue has more to do with the way his music sounds than with his birthplace or national allegiances.

Barber was born in West Chester, PA, educated at the Curtis Institute in Philly, and he lived and worked for much of his life in Mount Kisco, NY. Barber sought some of his musical education abroad, spending several years in Italy on a Rome Prize. Barber’s traveling and studying in Europe was not unusual; Copland, Thomson, Harris, and Bernstein also spent time studying with Europeans as they developed a distinctive American music.

In a 1939 article — “Modern American Composers” — David Ewen wrote about the then twenty-nine-year-old Barber that “[Barber] now promises to become the most important discovery in American music since Roy Harris[1].” It is interesting to note that at that early stage in Barber’s career, Ewen compared him to a composer who actively and aggressively cultivated his “American-ness,” and whose music was regarded as the epitome of American-sounding music. Furthermore, Ewen goes on to suggest that in the future Barber, because of his talent and skills, will contribute to further developing an American musical tradition.

A mere nine years later, in 1948, another article on Barber’s music appeared — this one by Nathan Broder titled “The Music of Samuel Barber.” Broder gives a summary of Barber’s works up to that point, and he is careful to defend Barber against the label, “neo-Romantic.” Broder claims that the use of tonality in Barber’s more recent works is a “return” to an earlier style and a technique employed to evoke a particular mood, rather than a consistent part of Barber’s musical vocabulary[2].

While it is true that in his works from the 1940s Barber did use more dissonance, syncopation, and serial techniques than in his earliest works, history has proven that Barber really is more of a neo-Romantic than not. His later large works such as his operas, Vanessa (1957) and Anthony and Cleopatra (1966, rev. 1975), are predominantly tonal and feature Barber’s well-known lyrical melodies, as well as a dose of post-Straussian chromaticism.

When compared to his contemporaries, Barber’s music simply sounds less “American.” Barber rarely uses American folk or popular song quotations, nor does he often employ jazz or popular styles in his music. One of the few pieces in which Barber does refer to American musical idioms is included in this CD set — Excursions (1941 – 2); however, Barber’s “most American” piece — Knoxville: Summer of 1915 (1947) is not.

I suspect that EMI’s decision to evoke American imagery on re-release of an already re-released album says more about the political climate and marketing strategies in the United States right now than it does about Barber’s music or his position as an American composer. The choice of a tattered American flag — waving bravely and persistently despite the weathering it has endured — reads as an attempt to capitalize on the surge of post-9/11 patriotism.

Although Barber is an American composer, the rural imagery on the CD cover does not speak to the America that Barber knew — the east coast cities or the upstate-NY village of Mt. Kisco. One would hope that the high quality of the performances and the popularity of the works on the recording would sell themselves.

Megan Jenkins

CUNY The Graduate Center

fn1. David Ewen, “Modern American Composers,” in The Musical Times 80/1156 (June 1939): 415.

fn2. Nathan Broder, “The Music of Samuel Barber,” in The Musical Quarterly 34/3 (July 1948): 325 – 335.