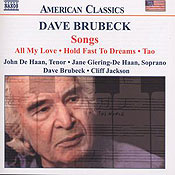

Dave Brubeck: Songs

John De Haan, tenor; Jane Giering-De Haan, soprano; Dave Brubeck, Cliff Jackson, piano.

Naxos 8.559220 [CD]

This problematic recording is another in Naxos’s “American Classics” series, an important body of releases that demonstrates the broad reach of American music across two centuries. While some of the recordings are decidedly novelties, they are welcome as such. William Henry Fry’s “Santa Claus” Symphony, for instance, deserves to be heard as well as mentioned in textbooks. The songs of Dave Brubeck, however, are certainly more than novelties, despite their not being as well known or as widely heard as the music of his justly famous quartet.

Brubeck’s wide expressive reach is evident here. Some of the songs recall his study with Darius Milhaud and the influence of early-to-mid-twentieth-century French music in general. “The Things You Never Remember” is one of these, as is “There’ll Be No Tomorrow,” an exceptionally beautiful song that begins with a Chopin-inspired introduction and displays its Romantic roots unashamedly. Other songs, such as “So Lonely,” reveal the depth of Brubeck’s harmonic versatility. “So Lonely” is a truly amazing song, in fact. Set to a simple lyric by Iola Brubeck, the composer’s wife and frequent lyricist, its chromatic, wandering melody perfectly reflects the neurotic denial of the text. It offers much for a sensitive interpreter. The four songs to texts by Langston Hughes are art songs influenced by, but well outside, the style of jazz for which Brubeck is best known. And yet “Strange Meadowlark,” perhaps the best-known selection on the CD, is well known from the instrumental version on the legendary Time Out CD, and later from a sung recording by the inimitable Carmen McRae. In other words, this is a jazz classic as well as a finely crafted and expressive song.

So, with all this extraordinary musical material, why is the recording problematic? The question begs several, more fundamental questions. Why is nearly every American singer trained in art song and / or operatic repertory incapable of singing convincingly in vernacular American English? Why are these singers incapable of successfully singing in any popular music-influenced style, let alone singing popular music? Why, when American music has in large part been a fusion of what American musicologist H. Wiley Hitchcock has called our “vernacular” and “cultivated” traditions, can American concert singers only sing in the “cultivated” style, or what has come to be accepted as such? And, finally, if these singers cannot sing this music, why do they insist on doing it anyway?

This is not the place to argue the success of some singers who have been critically lauded for their “crossover” recordings or performances. (I would argue that none have been successful, but I’m not arguing.) However, this recording is a demonstration of how badly a project can backfire if the singer is not at one with the repertoire and instead approaches it as if it were something it is not.

Are these songs “art”? Decidedly yes. They are art songs drawing from wide stylistic sources, and they are all perfectly and sometimes profoundly expressive of their texts. Does that mean, however, that they must be performed in such a wooden, inexpressive manner? John De Haan has a somewhat attractive tenor voice, but he seems clueless as to what he is singing. In the song “So Lonely,” mentioned above, he merely skates over the top of the song’s emotional content, providing no sense of emotion and suggesting no interpretive ability at all. Since Dave Brubeck is himself brilliantly and sensitively playing the piano for half these performances, we are left to wonder if this is how he imagines the songs being sung. Surely not. In “Strange Meadowlark,” De Haan crosses the line and sounds genuinely parodistic of an “art song” singer performing a jazz-pop song. If anyone can listen to him sing the phrases “To be singing oh so sweetly in the park tonight” or “You can sing your song until the dawn brings light” and not laugh out loud, he or she is of stronger stuff than I. De Haan performs as if he is doing the music a favor by “elevating” it to the status of art. What he doesn’t seem to realize is that it already is art. Carmen McRae signing “Strange Meadowlark” is art; De Haan singing it is pretentious.

De Haan does have some less troublesome moments, however. His performance of “Tao,” a setting for unaccompanied voice of lines from the Tao te Ching, is quite effective. Here, he seems to sing without his usual pose, and even his diction relaxes, allowing the singer to find the beauty in the sounds of the words as well as in their meaning. And the four songs to texts by Langston Hughes (which are not included in the accompanying booklet, presumably due to copyright restrictions), because they are composed in a style more demonstrative of what we might think of as “art songs,” do not seem as stilted or stiff as the other songs. Jane Giering-De Haan joins Mr. De Haan on some of these songs; her diction suggests that she, too, should stay away from the jazz influenced material, although her performance on these particular songs is fine.

Ultimately, this is not a recording I shall ever listen to again. I am happy to have discovered many of these songs, and I kept thinking of other singers I’d like to hear sing them. “So Lovely” would be devastating performed by Ute Lemper, for instance, and young African-American soprano Angela Brown could do lovely things with the Langston Hughes songs. What seemed to me to be the inappropriateness of Mr. De Haan’s style, however, made it a chore to get through the entire CD in one sitting. Whether you treasure the intellectual jazz of Dave Brubeck and the sensitive cool that comes through in so many of his quartet’s legendary recordings, or if you prefer his ambitious serious works like The Light in the Wilderness, this recording will disappoint. Because, unlike this composer, or many other American composers, who have so deftly fused the “vernacular” and “cultivated” traits in American music to create something unique, the principal singer of this set has no idea how to fuse anything. The stylistic imperative of “serious” singing prevents much of the singing from being taken very seriously at all, and it certainly prevents the singing from being appropriate.

Jim Lovensheimer, Ph.D.

Blair School of Music, Vanderbilt University