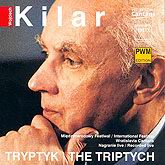

Wojciech Kilar: Tryptyk (The Triptych).

Izabella Klosinska (Soprano), Antoni Wit, conductor, Warsaw Philharmonic Chorus, Polish Radio/TV Symphony Orchestra.

DUX 0484 [CD]

Wojciech Kilar (b. 1932) is an exciting composer from Poland, and he may be best known in the West for his film scores, which include Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), Polanski’s Death and the Maiden (1994), Campion’s Portrait of a Lady (1996) and others. At the same time, Kilar also composes concert music, and his Tryptyk (1997) is a fine example of his work. Nevertheless, film is a useful point of reference in discussions of his style, since some of the techniques he used in creating effective soundtracks may be found in his other music.

Assembled into a single piece for a festival performance of the Wratislavia Kantans (on 16 June 1997 at Mary Magdelene Orthodox Church, Warsaw), Kilar’s Tryptyk is essentially a cantata in three movements: (1) Bogurodzica (1975); (2) Angelus (1984); and (3) Exodus (1981). While the individual movements were composed at different times, they fit together well, thus evoking the traditional image of the medieval style of painting an altarpiece as a triptych, where the panels have their own character and yet create a stunning effect when perceived as a unit. Kilar did not create a program for this work, but the religious tone of the texts suggests a sense of spirituality that conveys feelings of hope and, ultimately, triumphant joy.

The final movement is, perhaps, the most evocative, since its structure is based on a gradually increasing intensity of dynamics and scoring. It is a musical procession in the sense of Respighi, whose Pines of Rome contains a comparable, albeit shorter, passage. With Kilar, though, the music unfolds more slowly, which ultimately contributes to the exuberant ending. The sung text is from the Old Testament book of Exodus, and specifically Miriam’s song of triumph after the Israelites crossed the Red Sea into safety, with the pursuing Egyptian army drowned when the waters flowed back together. One of the most effective moments is near the end of the piece, when the choral forces shift from sung text to voiced shouts. The change from pitched to unpitched sounds suggests a dramatic scene so that when the music resumes at the end, its return forms a satisfying conclusion with its final “Hosanna.”

Such a use of the spoke — or shouted — voice in this movement has a parallel in the second, which begins with the choral recitation of the prayer “Hail Mary” in Polish. It starts softly, with a few voices, and in the numerous repetitions, subtly gains intensity, until the initially humble prayer becomes a vociferous shout. At that point Kilar shifts to traditional sounds, starting with an effective passage for soprano solo. The effect is cinematic and extremely effective, especially when Kilar eventually combines bells and other percussion into his score.

The kind of dramatic shift in timbre that is part of the “Angelus” is crucial to the first movement, the medieval text “Bogurodzica,” which is framed by extended passages for percussion. The martial tone of the percussion intersects the vocal music, and the chorus is asked to create ts own percussive sounds as piece begins. After the interplay of these elements, the choral setting of the medieval hymn at the core of this piece is effective in its subtle rendering of the text. It is a dramatic and compelling piece, like the other movements of this remarkable work.

Anton Wit conducts the work, and the musical forces he leads, the Warsaw Philharmonic Choir and the National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, give a fine performance. The soprano Isabela K