Giving seven performances of Donizetti’s Anna Bolena,

in its first Met outing, with internationally glamorous Anna Netrebko followed

by three more (not just one or two!) with a very different singer, rising

bel canto star Angela Meade, a local girl with a large local

following, has been a very happy choice. For one thing, this is a huge role in

a little-known opera; it was insurance for the house to have a cover available,

and any soprano capable of singing it well deserves a few chances to show what

she can do. I’d heard what Netrebko’s version on the air from Vienna last

spring, then by way of the Met web site’s free player on opening night here,

and again by way of the HDTV movie theater showing at the BAMRose cinema in

Brooklyn. On October 24, I attended Meade’s second Bolena in the

house.

Ildar Abdrazakov as Enrico

Ildar Abdrazakov as Enrico

Anna Bolena is perhaps the longest prima donna role in any of

Donizetti’s operas—and Anna may be his longest work, fully four hours of

music if uncut. It was his first hit in Milan (and, later, beyond the Alps),

composed in 1830 after a busy decade in Naples, the capital of a different

country at that time. He was determined to make an impression with a vehicle

for Milan’s reigning singing actress, Giuditta Pasta. The role may lack the

emotional spectrum of Bellini’s Norma, composed for the same singer

a year later, but she had plenty to do: a double aria sortita, three

highly charged duets (with mezzo, tenor and bass), a passionate trio, two

full-scale ensembles, and a famous mad scene that ranges elaborately from

pathos to rage. Canary coloraturas—this is not for you.

Overheard all about me in the crowd at the Met and at BAM: “This is such a

wonderful opera! With such lovely music! Why has the Met never done it

before?” If beautiful music and thrilling vocal drama were all that mattered,

the Met has only scraped the surface of the nineteenth century’s

possibilities, to say nothing of the eighteenth. In part, it’s a matter of

fashion. By the time the Met was built, in 1883, dramatic coloratura vehicles

were largely a thing of the past. Of Donizetti’s dozens of successful serious

operas, only Lucia survived the stylistic change wrought by Verdi and

his successors. Callas brought Anna Bolena back from a century’s

obscurity in 1957, but she didn’t sing it often, bequeathing the La Scala

production to Leyla Gencer. CaballÈ sang it just once, and acknowledged a rare

failure. Sutherland did not tackle it till she was fifty-seven, far too late to

make much of the character. Souliotis recorded it, unevenly as usual, but the

recording has its partisans. Sills was New York’s Anna: she

triumphed in it for a couple of seasons at the City Opera. Krassimira Stoyanova

sang Bolena in a drastically cut concert version with Eve Queler’s

Opera Orchestra of New York, and was spectacular in the raging fioritura of the

“Giudici” scene—the opera came to life for me then as it never had

before. She has not sung it anywhere since, perhaps because she lacks secure

high notes: Anna ranges all over the scale. You might say she sings

her head off.

Ekaterina Gubanova as Giovanna Seymour

Ekaterina Gubanova as Giovanna Seymour

Everyone remembers that Henry VIII wished to be rid of his first wife,

Catherine of Aragon, who had not borne him a son, and that the pope’s

unwillingness to grant an annulment drove Henry, an opponent of Luther’s

Reformation, to renounce papal supremacy. His passion for Anne Boleyn, which

was quite genuine (their love letters have been set to music), was at first

incidental to his wish to marry anyone capable of giving him a male

heir, but Anne, in addition, was part of the clique forwarding Protestant

reform. She was a highly attractive, sharp-tongued, neurotic femme fatale,

capable of inspiring both passion and hatred, and when her sons, like

Catherine’s, did not live (her daughter Elizabeth, of course, did), Henry

turned against her brutally. She was accused of assorted adulteries (high

treason for a queen), and sent to the block, to her great surprise (no one had

beheaded a queen before). That was in 1536. In Italy three centuries later no

one gave a hang about Protestant disputes, and the opera boils down to a

marriage gone bad and the trap laid by a brutal husband to catch his wife

in flagrante duetto. That’s an easy story for any audience to grasp,

as is the prima donna unjustly done to death.

Whether Anna ever really loved Henry and if she still does are questions

never mentioned in the libretto; this deprives her of a necessary dimension of

tragedy (if she did), or exculpates him (if she did not). Perhaps Donizetti

felt he had enough plot to set without facing such a question.

David McVicar’s production is large and dark, as if one look at the

five-story-high stage of the Met overwhelmed any sense of proportion. Getting

the proper atmosphere should not require such “authenticity.” I missed the

light touch Ming Cho Lee brought to the City Opera’s Tudor trilogy: A

tapestry down from the flies, a central playing area, a grand fireplace, an

occasional throne or dungeon chamber, and there we had it: Instant Tudor! At

the Met, Robert Jones’s sets look like the drearier rooms in a manor of the

period—not the ornate court rooms!—and they are two or three times too

high. They are vaguely historical backdrops, but they lack the color of

backdrops. Jenny Tiramani’s costumes, too, may well be in period—I do not

challenge that they are—but surely not everyone wore black and gray at a

brilliant Renaissance court. The chorus, homogenous enough in Donizetti anyway,

becomes a singing wainscot. The hunting forest, too, is gray, and the

triple-arched corridor of the last act is simple to the point of self-effacing.

Only the appearance of the swordsman at the end, Anna’s fate, seems to

attempt a visual coup, and the music ignores him, focused by this point

entirely on Anna.

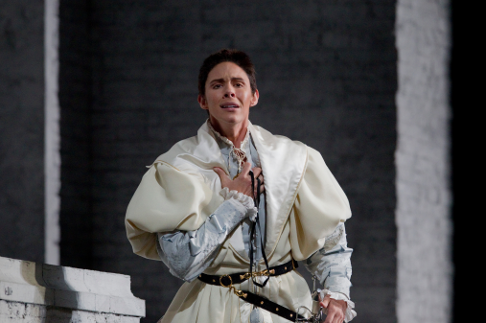

Stephen Costello as Lord Percy and Keith Miller as Lord Rochefort

Stephen Costello as Lord Percy and Keith Miller as Lord Rochefort

Anna Netrebko has a large and beautiful voice and can be a most affecting

actress, but her voice never seems as at home in Italian music as it did when

she sang Russian roles like Ludmila and Natasha. In bel canto, she suffers from

imperfect agility and a nasal delivery that does not breathe with the music.

The greatest bel canto artists school themselves to breathe in exactly the

phrases the composers wrote, so that the melody, ornamented or not, becomes a

melodious kind of speech, a vernacular poetry. I suspect Russian singers are

trained to breathe differently in their own ancient church-based tradition, and

very few of them escape it when singing western music, however beautiful the

instrument itself. This is my problem with Galina Vishnevskaya’s Puccini,

Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s Verdi and Ekaterina Gubanova’s Donizetti. A few

Russian divas, such as Olga Borodina and Ljuba Petrova, seem to have surmounted

this awkwardness; Netrebko has not. Too, I find her affect too heavy for

Bolena, and on the Opening Night broadcast she was under pitch for much of the

long night. This may be attributed to the strenuous rehearsal process and

first-night jitters: By the HDTV broadcast nearly three weeks later, she was on

pitch throughout, her voice in charge and easily produced. She has always been

a fine actress, and a queen in distress suits her very well. Though I enjoyed

her Vienna broadcasts of Bellini’s Giulietta and Amina very much, as sheer,

lovely sound, my personal preference would be to hear this sensuous instrument

in a more rewarding vehicle, such as Puccini’s Manon Lescaut.

That’s a role that rewards a heavy, beautiful voice, and when did we last

hear such a soprano attempt it? She’d be glorious.

I have heard Angela Meade as Elvira in Verdi’s Ernani,

Rossini’s Semiramide and Bellini’s Norma. The voice is

sizable over an exceptional range, but she wields it prettily, with genuine

trills, a lovely legato and soft but clear singing in the higher ranges that

falls on the ear with special grace. She is a rather stout woman, neither a

beauty nor a natural actress, but as Bolena, who must present her tormented

emotions over nearly four hours, she displayed impressive theatrical skill. In

Act I, she was regal and apprehensive, moving with a dignified posture; after

her accusation and trial, she seemed a much older woman, aged and bent by the

storm. Her madness was distracted and appealing. She did not imitate the

glamorous Netrebko’s highly personal gestures and expressions (the

reminiscent smile, the turn away from the audience for the final note), but

made the role her own within the restrictions of an existing production and

cast.

Tamara Mumford as Smeton

Tamara Mumford as Smeton

As a singer, Meade takes a while to warm up. In the first act, she seemed

rather to hover over the notes; there was no depth to them, and she seemed

merely to touch the highest notes and drop them. By the lengthy duet with

Stephen Costello’s Percy, however—Donizetti’s Act II, but the last scene

of Act I at the Met, where the opera is given with just one intermission—and

the great “Giudici” ensemble that follows, she had her musical feet on the

floor. Her duet with Ekaterina Gubanova’s Jane Seymour brought the thrilling

days of Sutherland and Horne to mind. As Meade demonstrated in Ernani,

she knows how to preserve her resources through a long night. By the long

concluding scene, she was in her element, tremendously affecting in the sweet

singing of “Al dolce guidami,” and then, with a terrific drop to almost

threatening depths that exploded in the anger of “Coppia iniqua,” her final

denunciation, a dramatic coloratura at last. The soprano who cannot make this

scene her own is not a proper Bolena; Netrebko, too, was fully in charge

here.

Gubanova is a Russian mezzo in the grand tradition of Arkhipova and

Obastzova, but the Met can’t seem to figure out what to do with her—or such

others of the ilk as Diadkova and Smirnova, the latter miscast in Don

Carlo. Gubanova is a superb Berlioz Didon (as she has demonstrated at

Carnegie Hall under Gergiev) and a superb Gluck Clytemnestre (under Muti in

Rome), but she has had some difficulty forcing herself into the molds called

for at the Met. To be fair, she only took on the role of Jane Seymour when

Elina Garanca, who sang it gorgeously in Vienna, pulled out due to pregnancy,

and if her sortita and its ornaments were messy, her duets with King Henry

(desperate) and Anna (poignant) had a happy intensity. Her voice mingles well

with Meade’s. But I wish they’d stage something Russian for her to sink her

palpable artistic teeth into—or Gluck’s Alceste.

Stephen Costello’s once light and liquid tenor is developing grit and

strength. This may forfeit some of his airy elegance, but will position him for

the forceful tenor roles of later Donizetti, Verdi and Puccini, the basic

Italian repertory. He made a handsome, credible figure in the far from credible

role of Lord Percy, Anna’s old boyfriend. Slim Tamara Mumford sang another of

her plummy performances, with a freer command of line up top than usual, in the

trouser role of the importunate minstrel, Smeton. Ildar Abdrazakov was

formidable in the somewhat underwritten (no aria) role of King Henry. His dark

bass must believably threaten each of the other characters in turn or the plot

makes no sense. In the present instance, the quailing of cast and chorus before

him was believable. Shaven-headed Keith Miller, such a treat as Zuniga in

recent Carmens, was impressive as Anna’s hapless brother,

Rochefort.

Marco Armiliato, whose conducting on opening night has been criticized,

certainly did not make the score sound shorter than it is, but he was attentive

to vocal line and Donizetti’s favorite “British” effect, dark strings

underscored by horns, rang out threateningly, gothicly, throughout the

night.

John Yohalem

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Bolena_Met_2011_03.png

image_description=Angela Meade as Anna Bolena [Photo by Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: Anna Bolena

product_by=Anna Bolena: Angela Meade; Giovanna Seymour: Ekaterina Gubanova; Smeton: Tamara Mumford; Percy: Stephen Costello; Henry VIII: Ildar Abdrazakov. Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra conducted by Marco Armiliato. Performance of October 24.

product_id=Above: Angela Meade as Anna Bolena [Photo by Marty Sohl/Metropolitan Opera]

All other photos by Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera