Some composer-anniversaries are feted – it sometimes seems as if Beethoven 250 is still running – and other musical milestones do not emerge from the shadows. 2021 was the 50th, 100th and 500th anniversary of the deaths of Stravinsky, Saint-Saëns and Josquin des Prez respectively, and the centenary of the birth of the Argentine tango composer, bandoneon player and arranger Astor Piazzolla – none of which, perhaps understandably given the on-going pandemic-related problems, have been much remarked in programmes and events this year.

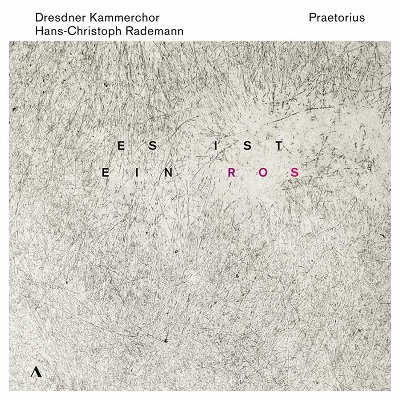

And, as the publicity for the Dresdner Kammerchor’s Advent/Christmas disc, Es is ein Ros, points out, 2021 was also both the 450th anniversary of the birth and 400th anniversary of the death – on his 50th birthday – of the German composer, Michael Praetorius (1571-1621): another overlooked landmark. The eponymous carol will doubtless be well-known to many – and, for many, a perfect synthesis of text and music. But, Oliver Geisler’s informative and engaging liner note reveals much more about the composer of whom we really know so little, divulging interesting information about his biography, career and compositional contexts, and about the works in this recorded programme, which span Praetorius’ career, from the Musae Sionia collections (1605-10) to the Puericinium (1621), by way of several of the many published collections in between.

A few remarks from Grove distil Praetorius’ practice and genius, emphasising his versatility, enormous creative output, especially of works based upon Protestant hymns, and his significant work as a theorist, most notably in the Syntagma musicum, published in his last years. Grove argues, too, that Praetorius’ work ‘displays an unusual degree of uniformity at a time of great change in musical history’.

Certainly, Praetorius is one of the most prolific and influential figures of the early German Baroque, whose compositions embrace both the most simple purity and the most sophisticated polyphony. They also – whether setting Latin or German texts – glisten and gallop with a faith characterised by confidence, joy and generosity, and conductor Hans-Christoph Rademann exploits this to the full. One such work is ‘Jubilate Domino’ in 9 parts, which really does ‘shout joyfully to God’. This is a swift, bright opening to the disc: the voices tumble in one after the other, in complex polyphonic conversations and configurations; the organ is light and energetic, spurring on the voices. This is a real feast of bright sopranos and tenors, but there is sonorous richness across the registers. And, as soon as one cadence seems to settle, the dust is kicked up and on the voices surge.

A predominant proportion of Praetorius’ oeuvre are arrangements of chorales for the Lutheran liturgy, and one such four-part chorale for the Christmas season, ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland’, encapsulates the alternatum practice, in which different verses alternate different forces and styles. Praetorius might have set out clear views about how many parts a setting might require, or whether instruments are obligatory, but there is still room for manoeuvre, since contemporary musicians were encouraged to tailor works for particular ensembles and environments. Here, there is lovely flowing momentum, and the singers enjoy the opportunity to make the major mode pungently piquant with the olfactory imagery, “und blüht ein’Frücht Weibesfleisch”. The solo voices are fresh and communicative, but not too ‘polished’; and they inter-change with solid pronunciations of collective faith. The ebbs and flows are persuasive, and in the penultimate stanza there is a lovely nasality that pushes forward the middle voices, preparing for the massed ensemble sound of the closing stanza – no ambiguity here, just a cosy-blanket tierce de Picardie embrace: “Lob sei Gott dem Heil’gen Geist/ immer und in Ewigkeit.” (Praise be to God the Holy Spirit / always and forever.)

Also from the 1607 Musae Sioniae Part 4, comes ‘Von Himmel hoch, da komm ich her’, the complexity of which affirms the tone of reverence. The twists and turns at the harmonic corners are exploited expressively, as are the sequences of suspensions and the brassy colours which conjure majesty. Often high voices seem to drop in from celestial spheres. The energy never flags, and each verse is treated extensively and sumptuously, the velvety layers accruing in rich abundance. The changes of tempo and time signature are seamless and build into an euphoric celebration.

But, never does the coherence of the ‘whole’ dominate the detail. So, in the second stanza a luscious density is summoned to capture the absolute certainly of the final two lines, “ein Kindlien, so zart und fein,/ das soll eu’r Freund und Wonne sein” (a Child so tender and fine,/ He shall be your joy and delight); while in the next stanza the brass initiate counterpoint which heralds the wonder and assurance of the heavenly choir who proclaim, “Es ist der Herr Christ, unser Gott”. The fourth verse begins more gently, and homophonically, but it’s not long before the infectious cross-rhythms pull performers and listeners alike back to the dance, swinging all around in a euphoric haze, and easing finally into a comforting hug – “des freuen sich der Engel Schar” (the angels are happy) – though even that can’t repress the energy, as every ounce of glee is squeezed out of the music in the closing bars.

A Magnificat (‘super Angelus ad pastores ait’) offers full festal fayre, blending song and dance, art and folk, Latin and German texts. It’s almost as if Praetorius had musical ADHD, the creative fruits of which we can enjoy four centuries on! But, even amid such richness there is restraint, the solo voice cleansing the palette from time to time. ‘Quem pastores laudavere’ glows fiercely, the solo voice and theorbo throbbing through the pronouncement of the glorious King’s birth, “natus est Rex gloriae”, the dance-like episodes flying with Italianate flair. A beautifully decorated cornett solo opens ‘Der Morgenstern ist aufgedrungen’, and here, as the voices repeatedly enter on the second beat of the bar, there is a wonderful fluidity, conveying enthusiasm, joy and ascension. In ‘Angelus ad pastores ait’ we hear how timbre and spatial expanse can create energy: and, though the harmony is quite static at the start, release is offered by the lightly tripping “Alleluia”, and subsequently the dissonant crunches and crimps are brilliantly expressive.

‘Resonet in laudibus’ is essentially a chorale-dance, which again alternates Latin and German text and in which the triple time makes the high solo voices fly while the ensemble choir overflows with firm conviction. At the start of ‘Puer natus in Bethlehem’ the brass announce their adoration of the king of Sheba, but subsequently dignity does not inhibit dynamism, and the music pushes forward with compelling pace, phrasing and panache – infectious, impetuous and expansive, especially in the triple-time repetitions. There is purity in ‘Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern’, and powerful nobility in ‘Deo patri sit gloria’: in the latter the lower tessitura seems to inject some gravitas initially, but ultimately there’s no holding back and one fears the musical sentiments will burst their seams before the close!

And what of the titular carol? Well, the brass offer nasal warmth, making me think of the burgeoning flame of newly-lit candles spreading their glow and heat, as glasses of mulled wine warm chilled hands and hearts, and though I might prefer a more intimate rendering, with smaller forces, there is no denying the lovely contrast of the voices’ pressing pace and delicate inner dialogue in the organ, and, in the final verse, the comforting fullness of the a cappella voices and their gentle retreat at the close. We also have the opportunity to compare Melchior Vulpius’ 4-part canon on the same chorale theme, and here there is clarity and focus as the voices unfold and withdraw, like the petals of a delicate flower opening and closing.

Do I have any misgivings about this disc? Well, perhaps the intensity is rather unalleviated, and can leave one feeling a bit emotionally bloated, as if one has eaten too many roasties and sprouts at Christmas lunch, washed down with one glass of red wine too many. But, there’s a neat parallel between Praetorius’ music, written for specific occasions, and this disc, essentially assembled for a Christmastide music market. In both contexts, there is genius in the composition, compilation and execution alike. And, one thing that the Dresdner Kammerchor establish without doubt: Praetorius is not just for Christmas.

Claire Seymour

Isabel Schicketanz (soprano), Jonathan Mayenschein (alto), Christopher Renz (tenor), Martin Schicketanz (bass), Dresdner Kammerchor, instrumentalists, Hans-Christoph Rademann (conductor)

Es ist ein Ros: Michael Praetorius – ‘Jubilate Domino’; Melchior Vulpius – ‘Es ist ein Ros entsprungen’; Michael Praetorius – ‘Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland’, ‘Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her’, Magnificat super Angelus ad pastores ait, ‘Es ist ein Ros entsprungen’, ‘Quem pastores laudavere’, ‘Der Morgenstern ist aufgedrungen’, ‘Angelus ad pastores ait’, ‘Resonet in laudibus’, ‘Puer natus in Bethlehem’, ‘Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern’, ‘Deo patri sit gloria’.

Accentus ACC 30505 [61:31]