The Festival International de Film d’Opéra à Entrecasteaux (a tiny village in Provence not far from the A8 autoroute connecting Nice and Marseille). The second edition of this unique summer festival takes place August 12 and 13 on the old wheat field below the village’s imposing chateau (lead photo).

The 2024 offerings are American film director Joseph Losey’s 1979 Don Giovanni (August 12), and French writer/director/presenter Frédéric Mitterrand’s 1995 Madama Butterfly (August 13). Both film creators had extraordinary lives — Losey, born in 1909 died in 1984, and Mitterrand, born in 1945 died last April.

The Losey Don Giovanni was a “must-see” film when first released, the Mitterrand Butterfly has assumed stature as a more real version of Puccini’s verismo masterpiece.

Joseph Losey was a major figure in New York City political theater in the 1930’s. He made a pilgrimage to Russia in 1935, attending a seminar by legendary film director Sergei Eisenstein, where he initially met Bertolt Brecht. Released from the U.S. military in 1945 he then worked with Brecht (by then in Hollywood exile), ultimately staging Brecht’s play Life of Galileo in 1947. That same year he directed his first film The Boy with Green Hair. In 1951 he remade Fritz Lang’s famed classic M, but it was set in L.A. rather than Lang’s Berlin.

Losey, like many liberal minded Americans of the epoch, came to be considered a threat to the American political order. Summoned by the infamous House Un-American Activities Commission (HUAC) and termed a Stalinist agent by the FBI, he was blacklisted in Hollywood. He decamped to Britain where he worked with famed British political dramatist Harold Pinter, directing the films The Servant and The Go-Between, working as well on a Pinter adaptation of Proust’s novel A la recherche du temps perdu. Losey gained fame in France by directing Monsieur Klein (1976), a film about the 1942 round-up of Parisian Jews.

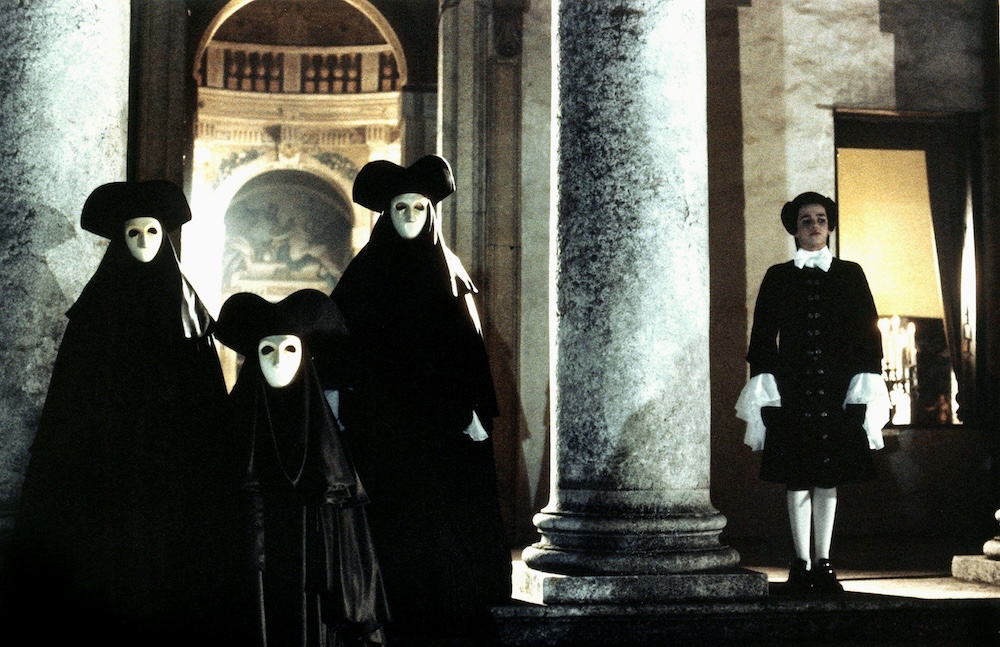

It can be of no great surprise that Losey’s signature mixture of film noir, naturalism and expressionism found vent in his cinematic vision of Mozart’s epic Don Giovanni (the thirty-fifth of his 38 films). Plus filming this great operatic masterpiece unleashed Losey to indulge in his exuberant detailing, and the grandeur and awe that illuminate his entire filmography.

It will also be of no surprise that Losey prefaced his Don Giovanni with a statement by the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, “The old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” Nor is it surprising that he ignores the historical Spanish setting of the Don Juan legend in favor of the decaying atmospheres of Italian architectural neo-classicism, specifically in the Andrea Palladio (1508-1580) designed Villa Rotunda and his Teatro Olympico (in Vicenza, near Venice) where most of the film’s action takes place. The morbid winter vapors of the Po river delta figure heavily as well. The film earned a 1980 César award for best production design.

The vast geography and the diverse atmospheric locations of the film separate the filmed action from the recording studio realization of the Mozart score. Losey however did not use actors mouthing the words to create the characters envisioned by Mozart’s librettist Lorenzo de Ponte, instead he used the actual opera singers, among the finest, and most famous singers of his day — Ruggiero Raimondi, José Van Dam, Edda Moser, Kiri Te Kanawa, Teresa Berganza, Kenneth Riegel.

In an era when acting for singers was far less important than their voices, critical questions loom for a contemporary audience — why did Losey choose to film opera singers rather than actors, does the film succeed as opera, does it succeed as film, or perhaps does it somehow define opera on film? And, most interestingly, does the Losey film deconstruction of Don Giovanni attain the revisionist stature of the two Tcherniakov deconstructions staged recently at the Aix Festival, and the new Castelucci version to be seen this summer in Salzburg.

Fréderic Mitterrand, nephew of French president (1981 to 1995) François Mitterrand, needs no introduction to the French public as, foremost, he has the advantage of a very prestigious family name. Frédéric remained an avid and always controversial player in France’s cultural life for the past 50 years, first as a critic and an entrepreneur of art films, then as a television producer and director, and nearly always as a radio personality. In 2009 Nicolas Sarkozy named him as France’s Minister of Culture (he effected many highly controversial changes) in spite of Frédéric’s boasts of having paid for sex with young boys in Bangkok, a revelation offered in his 2005 autobiographical novel La Mauvaise Vie.

It will be then of little surprise that his venture into producing opera on film should recount the tale of a 15 year old Japanese girl having sex with an American sailor.

Mitterrand filmed his 1995 Madama Butterfly not in Japan, but in Tunisia, continuing a long association with this north African country (a French territory from 1881 to 1956, and where French is largely spoken). Mitterrand in fact has two adopted Tunisian sons, Saïd Kasmi-Mitterrand, born in 1971 and Jihed Guasmi-Mitterrand, born in 1991.

Always well connected to the upper echelons of Parisian life, Mitterrand enlisted the soon-to-be-appointed music director of the Opéra de Paris, American conductor James Conlon to join him in casting the opera, as well as to adapt the Puccini score to the film. Mitterrand and Conlon sought singers for the filmed opera who would cinematically evoke the realism of the characters in Puccini’s 1904 opera, perhaps even in David Belasco’s gritty 1901 play. They found a young Chinese soprano named Ying Huang to portray a believable 15 year old Cio Cio San, and a handsome, young American musical comedy singer named Richard Troxell to be Pinkerton. Both singers gained a certain fame because of this well-regarded film, and went on to small careers in real opera houses.

The Tunisian location of the film effectively evokes a Nagasaki of nearly a century before the film was made. With the balance of the cast reflecting the appropriate ethnicities of the Puccini characters, the film responds to the current sensibilities that object to the artistic exploitation of other cultures, i.e. forcing European singers into Asian make-up, now considered as insulting as disguising a white Otello in black-face. [A very recent solution to this problem was addressed in the recent Tokyo Nikikai Opera Foundation production of Madama Butterfly, a co-production with San Francisco Opera — the Butterfly story was told by the now adult, half-breed love-child Trouble. The ethnically appropriate cast was directed by a Japanese stage director, with costumes by a famed Japanese couturier.]

Few critical questions present themselves for the Mitterrand Madama Butterfly. The young Chinese soprano may not possess the sumptuous voice expected of an opera house Butterfly, the furious Bonze appears only as a flying ghost. Most troubling is the black and white film montage of Nagasaki that is shown during the humming chorus.

There is no doubt that the Mitterrand Butterfly realizes what film can do for opera, but the question remains, is it opera on film, or is it a film with a soundtrack? The production won a César for best production design in 1996.

Michael Milenski

There is no charge to attend these 9 PM screenings. There is easy, free parking, and picnicking is possible (and encouraged) from 7:30 PM