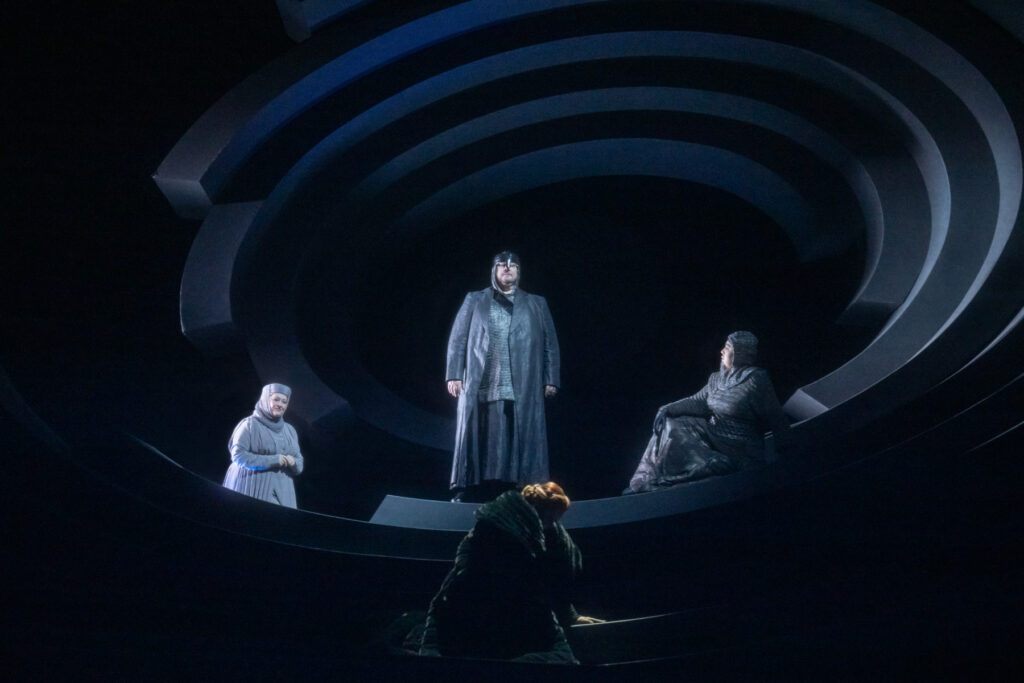

‘A monument to this most beautiful of all dreams’ is how Wagner described the intoxicating contemplation of love that is his Tristan und Isolde, and it is essentially as a dream that Nicholas Lehnhoff presents the opera in his production for Glyndebourne – subdued and almost entirely stripped of any set and action, emotion certainly recollected in tranquillity here, not fever. We are invited to peer into this private vision through the screen which opens out in the black veil before the stage, after the Prelude has played out. It reveals a series of concentric circles, a static vortex that seems to worm its way backwards into the oblivion sought by the lovers, but symbolically traps them in the state of yearning and desire from which they desperately search for release. But it’s also a physically cumbersome set, as the singers sometimes teeter on its curves before finding their balance, and Karen Cargill has already sustained injuries during rehearsals which resulted in her withdrawing from this performance as Brangäne.

The general philosophical idea of this ‘opus metaphysicum’ (Nietzsche’s description) is realised here from the lighting and atmospheric tricks of Roland Aeschlimann and Robin Carter’s designs, evoking the dark realm of night to which the lovers hope to escape from the dangerous, prying and stultifying world of light and the everyday. That threat is manifested by the irruption of light through an aperture at the superficially triumphant moment in Act One when reality intrudes upon Tristan and Isolde with the arrival of King Marke on the boat. The ‘vast wave of the world’s breath’ of Isolde’s Liebestod into which the lovers seek transfiguration and consummation is adumbrated by the purple-blue haze which appears once they drink the love potion a little before Marke’s arrival, and that hue pervades Act Two until dawn again encroaches on their emotional and psychological paradise. It doesn’t recur until the Liebestod, after Tristan has suffered his agonies in the scorching glare of Act Three.

As a symbolic idea the play of light is simple and effective, but it doesn’t make for much of a dynamic drama across four hours, especially when the choreography is also static. Tristan and Isolde’s interactions are chaste and passionless; when they do hug, it’s more like an act of conciliation or compassion, in the manner of Parsifal, than any act of sexual desire. Curiously there is more human warmth in the relationship between Tristan and Kurwenal in Act Three, as the former languishes from the wound inflicted by Melot.

Paradoxically, Robin Ticciati’s reading of this doom-laden, shadowy score could best be described as lucid. Instead of yearning intensity and ecstasy, the overall character is one of restraint and caution. Although he has a grasp of the music’s wider structures, or what Wagner called its ‘melos’, that is taken quite tamely at a fairly relaxed tempo. Climaxes and more dynamic passages are reached quite suddenly and involuntarily like a spasm, rather than worked up to in a more controlled and directed fashion on a broader scale, so quieter sections are sometimes restless and aimless. Often the London Philharmonic sound like a slightly smaller orchestra than usual, characterising sensitively the music of a more intimate or mystical nature, as at the throbbing beginning of ‘O sink hernieder’, but electricity and force tend to be missing from more extrovert sequences.

Stuart Skelton still has Heldentenor heft in the title role, but it’s not always exactly focussed in timbre, and is sometimes effortful rather than potently sustained. Miina-Liisa Värelä’s starts in a somewhat brittle and wiry vein, but opens out more brilliantly as the work proceeds. Although she comes under pressure in higher and louder notes, happily she remains radiant and in command for the climactic Liebestod. Marlene Lichtenberg’s Brangäne begins well, with rounder, more powerful tone than Isolde, but for Act Two’s haunting sequence at ‘Habet acht!’, enunciated atmospherically from somewhere outside the auditorium, she sounds decidedly woozy, with one or two notes wide of the mark. Shenyang’s Kurwenal is more secure, vigorous and reassuring, while Franz-Josef Selig expresses world-weary disappointment and regret in his two monologues, and particularly in a fine sombre duet with the bass clarinet for that in Act Two, once Tristan and Isolde have been found by Samuel Sakker’s peremptory Melot. This Tristan draws us coolly into an inner vision rather than overwhelming with searing emotional force.

Curtis Rogers

Tristan und Isolde

Composer and Librettist: Richard Wagner

Cast and Production staff:

Tristan – Stuart Skelton; Isolde – Miina-Liisa Värelä; Brangäne – Marlene Lichtenberg; Kurwenal – Shenyang; King Marke – Franz-Josef Selig; Melot – Samuel Sakker; Young Sailor/Shepherd – Caspar Singh; Steersman – John Mackenzie-Lavansch

Director – Nikolaus Lehnhoff; Revival Director – Daniel Dooner; Designer – Roland Aeschlimann; Lighting Designer – Robin Carter; Conductor – Robin Ticciati; The Glyndebourne Chorus and London Philharmonic Orchestra

Glyndebourne Opera House, East Sussex, Friday, 2 August 2024

Top image: Brangäne (Karen Cargill) and Isolde (Miina-Liisa Värelä).

All photos © Glyndebourne Productions Ltd. Photography by ASH.