Nobody should ever assume that creative artists constantly engage in mutual back-slapping. Tolstoy’s verdict on Wagner’s Siegfried, the second day of the Ring cycle, was vicious: “A stupid puppet show not even good enough for children.” So why can it be argued that his judgement was faulty? Like the teenage Smith in Sillitoe’s The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner, Siegfried is entirely on his own. Who can he really trust? He spends virtually the whole opera in a desperate search for love. In part, Wagner’s material is about the pressure imposed upon Siegfried to perform heroic deeds, over and over again: re-forging his father Siegmund’s sword, slaying Fafner, disposing of Mime, breaking through flames to awaken Brünnhilde. But Wagnerian heroes need to remember that, like all instrumentalists, they are only as good as their last performance. This adds to the stress.

Staging this opera in a confined performing space is in itself a herculean task: the action needs to move from the domestic squalor of Mime’s hut through a recreation of a Wagnerian forest to the heady heights where Siegfried is destined to meet the only love of his life. Commendable though all the efforts of Regents Opera are in realising such challenges, not least by the small army of stage-hands beavering hard during each interval to effect complicated scene changes, not everything coheres or convinces. Here, Act 1 is so successful and so involving, by dint of the entire immersive experience, that what follows represents a distinct falling-off in creative inspiration. We have something as remembered perhaps by Tracey Emin: books scattered all over the floor, a couple of bucket seats, a rickety standard lamp that keeps on flickering until it finally gives up the ghost, a cooking pot containing green slime and, in a deliberate allusion to Dadaism, Marcel Duchamp’s urinal as a central feature of Siegfried’s forging activity.

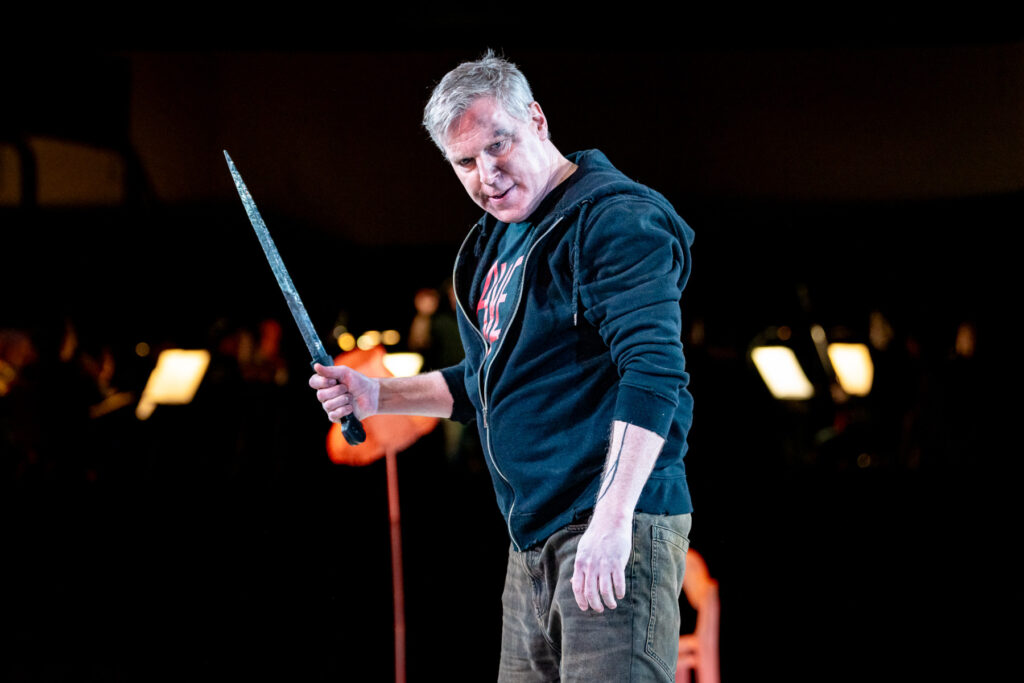

At the heart of this first act are the intense exchanges between the young hero and his foster-father Mime. In Peter Furlong’s Siegfried we had a proper Heldentenor, with ringing top notes that repeatedly popped like champagne corks, an abundance of physical exertion that extends to lifting Mime off his feet and whirling him around, together with impressive self-belief advertised as “Slayer” on the front of his costume top. His repressed childhood traumas surface in the teddy-bear he clutches. Yet at times I wanted the stamina he maintained to the very end to be modulated more in the voice: not everything Siegfried sings needs to be so turbo-charged. About Holden Madagame’s Mime I have no reservations whatever. Quite apart from the incredible acting skills that include malicious smiles, somersaults, spasms and ferocious endeavours on his writing-slate, there is the vocal range. This Mime has a wonderful snarl, a piercing whine, a vibrant braying, an ability to growl from baritonal depths, a parlando style that maximises clarity of delivery, and an ache in the voice that touches the soul. Equally strong is the Wanderer of Ralf Lukas, in exceptionally good vocal form, relishing the coal-black tones at the lowest end of his bass register. He first appears as a tradesperson summoned by Mime to fix his lighting disaster, sporting dark overalls and a pair of spectacles with a darkened left lens, carrying a requisite tool box. There are countless comical touches that accentuate the idea that Siegfried represents a Wagnerian scherzo, with whooping horns and throbbing strings during the forging scene.

Act 2 already shows signs of an over-fussiness in the staging. Six video screens at floor-level adorn the central space, but instead of arboreal landscapes there are flickering images of slowly decaying fruit and vegetables (a blackened banana was especially striking), interspersed with pictures of Sieglinde, and attempts at suggesting a party atmosphere with glasses of bubbly handed out to Mime and Alberich on their arrival by the Woodbird attired as a catering assistant. At the opposite end is a translucent box-like construction, illuminated from within in successive red, amber and green, which functions as Fafner’s cave. When the giant eventually emerges, he is wearing a sparkly costume suggestive of a pangolin or armadillo. Craig Lemont Walters is everything you would expect a reptile to be: twisting and turning, his tongue outstretched in anticipation of attendant prey, with a cavernous voice that chills the marrow, from his early “Lasst mich schlafen!” to his stark warning to Siegfried, “Acht auf mich!”. I really felt for this Fafner: required to appear in drag, complete with a long flowing wig, just before his slaying by Siegfried, he then divests himself of all his coverings but for a white diaper, only to lie outstretched on the stage for the best part of fifteen minutes until his body is unceremoniously despatched through an opening in the floor. What a way to go! A camp episode, reminiscent of Folies Bergère, with Mime and Alberich in top hats, adds nothing at all.

Act 3, the vocal contributions excepted, proves to be a disappointment. The final confrontation between Wotan and Siegfried takes place in semi-darkness, after a splendid declamation by Mae Heydorn’s Erda, all ghostly in appearance, with the dark molasses of her superb alto range very effective. However, what fails to come off satisfactorily are the events on Brünnhilde’s rock. It is partly the composer’s fault: it is though at this point he is driving with the hand-brake still on, the music only very gradually building to the consummation of the union between Brünnhilde and Siegfried. The staging really doesn’t help. The two leading characters are behind white string curtains or glitter fly screens that enclose a bridal chamber with additional strips of voile netting which are later torn down from their interior props. The Woodbird casts a flurry of downy feathers from a white satchel. Even more frustratingly, Brünnhilde is not dormant on a rock but stands statuesque for a seeming eternity in an haute couture bridal gown, her protective “breastplate” another external layering of plain tulle. Siegfried has to contend with a white top consisting of ridiculously overlong sleeves constantly being pulled back (was I missing something of deep symbolic significance here?), while the two protagonists first pace up and down like two prize fighters sizing each other up and itching to start, and who then stand on opposite yet very distant plinths. Physical desire is nowhere in evidence until the very end, not even an outstretching of arms and hands. The indications are of an estranged couple in a mutual sulk, hardly able to bear the other’s presence, rather than an outpouring of hormonal energy from two excitable young individuals. This was all the sadder, because both Catharine Woodward, as a radiant, technically secure Brünnhilde, and the vocally indefatigable Siegfried, were at the top of their game, giving full expression to the growing ecstasy present in the score.

Ben Woodward and the sterling musicians in his ensemble deserve full praise. Once again, there were felicitous instrumental details, not least from Francesca Moore-Bridger’s horn solo when Siegfried awakens Fafner. I recall the dark orchestral colours that Woodward often highlighted, the chamber-like delicacy of the Forest Murmurs and the diaphanous textures when Siegfried sings of the longing for his mother. Musically, this performance vastly outshone the staging. And where else will you see the conductor walking around in the intervals engaging with and talking to ordinary members of the audience? Such corporate commitment is nothing short of a triumph.

Alexander Hall

Siegfried

The second day of The Ring of the Nibelungs

Libretto and music by Richard Wagner

Sung in German and with English surtitles

Arranged for Regents Opera by Ben Woodward

Cast and production staff:

Mime – Holden Madagame; Siegfried – Peter Furlong; Der Wanderer – Ralf Lukas; Alberich – Oliver Gibbs; Fafner – Craig Lemont Walters; The Woodbird – Corinne Hart; Erda – Mae Heydorn; Brünnhilde – Catharine Woodward

Director – Caroline Staunton; Set Designer – Isabella van Braeckel, Lighting Designer – Patrick Malmström; Regents Opera Orchestra – conductor, Ben Woodward

York Hall, London, 13 February 2025

Top image: Siegfried and Catharine Woodward as Brünnhilde

Photos © Steve Gregson

The second of two cycles begins on 23 February