If any Puccini opera can evolve with the times it would probably be his Madama Butterfly. Indeed, it has been widely adapted to film – firstly by Fritz Lang in 1919 – to the stage, novels, animation and been set in Japan, China, Tunisia, Thailand and Cuba. It has transcended the boundaries of sexuality, although has never entirely steered clear of the original concept of doomed relationships. Beyond Puccini’s opera directors have often set Madama Butterfly in times of revolution.

Huang Ruo’s M. Butterfly, based on the Broadway play by David Henry Hwang, sets the opera during one of the most turbulent periods of the postwar twentieth century over a more than twenty-year period, from the 1960s to the 1980s. The history is geopolitical, but this is more about the decline of imperialism rather than its ascendency. The Vietnam War is raging; but this is a war of attrition that will reset political power. In China the revolution is one that imposes cultural conformity and repression. Although Hwang’s play has often been seen as un-American the choice of a French diplomat and his involvement in espionage is more significant. Post Suez, few western countries experienced such a rapid decline in their imperialist ambitions, or their own political instability. (Unsurprisingly, M. Butterfly has not been performed in France.)

Against this background, Hwang and Ruo are able to do one significant thing and that is to change our attitude to how the opera is seen to contemporary eyes. Even if the orientalism of the original remains intact (we have just moved from Japan to China), it is the gender identity and sexual fluidity which is different. Linked to the history of imperialism is racism and here I found myself asking the question of whether attitudes towards it were different between Puccini’s opera and Ruo’s. If it seems more explicitly so in M. Butterfly I wondered if the connection was more tenuous to the idea of imperialism simply because the contemporary view of racism is one we recognise differently – not least because it has become more complex too.

When M. Butterfly was first performed – at Sante Fe Opera in 2022 – it was fully staged. For the UK premiere of the work, at the Barbican, we got a concert performance of the opera – albeit one that was semi-staged. There are both advantages and disadvantages to this. The opera is in three acts (as is Puccini’s), and Act 1 is clearly disadvantaged by not being done in an opera house given the fact it has seven scenes. In Sante Fe there were two sets of dual tiered boxes that were moved on sideways, hence giving some fluidity to the complexity of what happens in Act 1. In this concert performance it simply looked muddled and very busy, rather like moving furniture around – placing a lamp here, a chaise longue there. At the other side of the stage we were either in Fresnes Prison or at the desk of the French Ambassador to China (with the exception of the rather odd scene 4 where Gallimard and Marc were inside a gym changing room). Acts 2 and 3 worked much better – indeed, even the People’s Liberation Army troops scene (minus the troops) worked well simply because the music and chorus for it conjures up such a thrilling vision of the scene itself and the on-screen projection did much to seer the impression of Mao’s revolutionary zealousness into the mind.

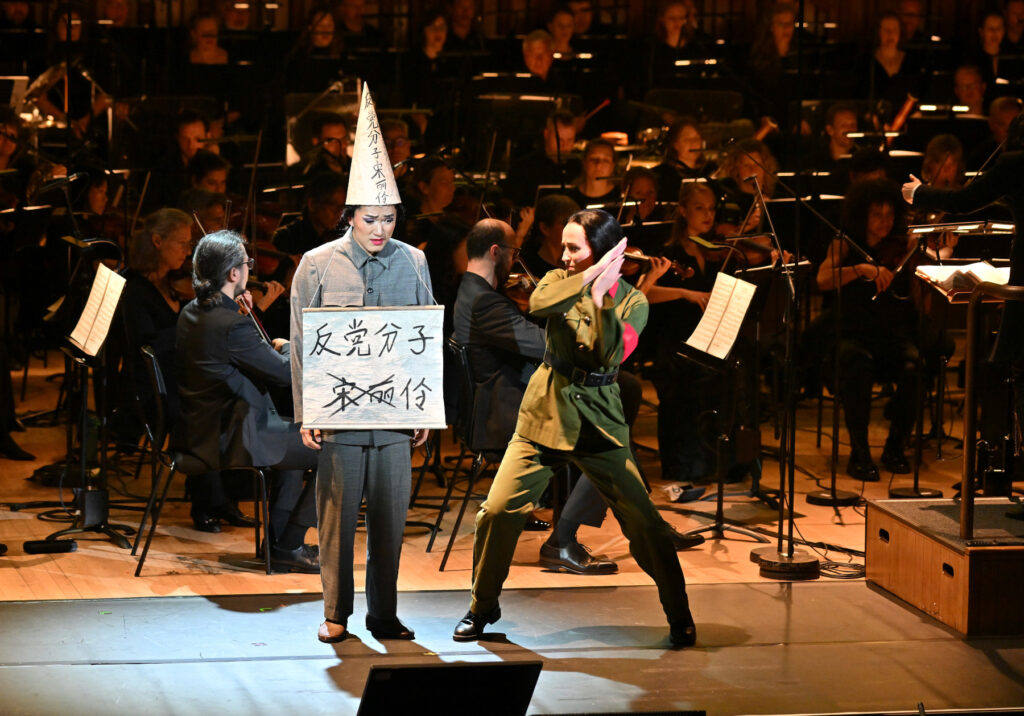

Greg Emetaz’s projections were highly evocative. Using newspaper footage of the espionage case, photographic stills (Mao’s Little Red Book) and settings where the original staging would have used scenery (such as for some of the geographical mapping) they caught the attention. However, I have probably never seen a more industrially boring interior for what would have likely been a more splendid exterior of an embassy building. Some graphics were startling – of blood sweeping across the screen at the very end, and of an opening image of Beijing that my eyes apparently refused to see for some time beyond the shape of a butterfly. James Schuette’s costumes were superb – Song Liling in splendid Chinese silks, Comrade Chin Echt revolutionary, with five-pointed red star and Mao cap, and Song’s powerfully done shaming in Act 2 where she is forced to where a dunce hat and placard round her neck.

M. Butterfly is scored for a smaller cast than Madama Butterfly and two roles double up: (Comrade Chin/Shu Fung) and (Manuel Toulon/Judge). If Puccini’s opera is tightly composed (no wonder since he wrote five versions of it before eventually publishing it), then Ruo’s does have some weaknesses. Act 1 is problematic on several levels. I could have done without Scene 4 (Gallimard’s tennis-playing sidekick Marc and set in a changing room). Some of the embassy scenes seemed over-extended. Acts 2 and 3 are superb, however – and also have the best music in the opera (the PLA troop march and scene is just wonderful). If there is sometimes a tendency for American twentieth century opera composers to never quite know how to end an opera without making it seem eternal (Philip Glass is notorious here) then Ruo avoids this, even if M. Butterfly does end with one of the longest solos of the entire work. Perhaps less convincing is a libretto which relies on some duets where Gallimard sings in English and Song in Italian – and it was a risk to include Puccini’s Un bel dì, which neither flatters the words around it, nor the music. At best English simply sounds disjointed with the orientalism expressed here, even if it is something that is being radically reinterpreted. At worst, it sounded brutally clashing, especially in the duets between Gallimard and Toulon where too often the tonal blend of the voices didn’t feel distinctive enough. That almost all of these problems were shunted into Act 1 made the performance one of two halves – and something of a frustrating one.

There were two absolutely standout performances for me on the evening – the BBC Symphony Orchestra and Kangmin Justin Kim’s Song Liling. Countertenors have always been something of a revelation to me in contemporary opera – Akhnaten is endlessly fascinating for me, for example. Perhaps why they seem so appealing is because of a willingness to break down barriers in opera. If the register is something of an outlier, so do the singers, I think. What was unusual about Kim’s performance was how astonishing he was in fleshing out Liling with so much contrast. There was rawness and tenderness; vulnerability and power. He gave us the illusion of having no single gender here: there was the feminine, and there was the masculine and in between the cultural conditioning to strip him of sexual identity altogether in a China where gender would become almost neutral. Kim’s Song was a woman complex enough to engage in espionage, and deceitful enough to conceal a fake pregnancy. If Song can never be naked as a woman where her identity would be revealed, then he can be stripped bare as a man and the deceit uncovered (countertenors, it seems, rarely have a problem getting naked on stage and Kim was no exception here). When Song has transformed into a man in Paris, the theatre of cruelty that is enacted in court made me think of Song as one of Jean Genet’s gay villains.

If Kim’s stagecraft was utterly convincing, then his singing was just magnificent. There is much beauty in the voice – gorgeous pitch, ethereal phrasing and tone. What was important here was believing that sexual fluidity would work; one didn’t even have to close one’s eyes to imagine the voice belonged to anyone other than Song Liling so convincingly done was it. If the English libretto would sometimes sound mannered and stilted with some of the male soloists that was not the case with Kim – it flowed like a stream and had the lightness of silk to the text where it otherwise might have sounded clipped. Italian solos were vividly done and drenched in colour. The legato was effortless, but so too was the burning emotion: this was singing that was seared in a furnace, and wielded with the precision of a seppuku knife. A tour de force of a performance, and absolutely compelling to watch.

René Gallimard, the French diplomat, is the largest role in the opera – indeed, he barely seemed off stage at all during Act 1. However, whether one has much sympathy – or perhaps empathy – towards this rather hapless man is debatable. Is he victim or oppressor? Is he a Puccinian orientalist, or the western liberalist? In a stunning reversal of roles, Gallimard transforms at the end of the opera into Butterfly – another example of M. Butterfly’s framing of sexual fluidity and gender identity working in binary ways. When Butterfly’s immolation finally comes it feels distinctly less feminine and more like the masculine Samurai Bushida.

Mark Stone, another of the original singers from the Sante Fe production, took a little time to settle into the role – although, again, I wondered if the libretto was the problem rather than the soloist. I think he was at his most compelling when singing alongside Kangmin Justin Kim’s Song Liling where the voices were nicely contrasted; less convincing for me were the long duets between Gallimard and Toulon where my attention wandered. At his best, such as in the tenderness of the love duet with Song at the end of Act 1, or in his final aria at the end of Act 3, he was often sublime – in the final one flexing the poised dividing line between the masculine and the feminine with breathtaking beauty and emotion. It was one of the highpoints of this performance.

Fleur Barron’s Comrade Chin was in part menacing and chilling, her mezzo intoned with darkness and threat: “Follow the Communist Party forever!/Follow Chairman Mao forever!”. I didn’t quite find Kevin Burdette’s bass rich enough for Manuel Toulon and he sometimes weaved through his lines with a less than iron grip. The BBC Singers, however, were just thrilling. They were nowhere better than in their Communist Party scene (Act 2, Scene 2) as the PLA Troops: “We are the People’s Liberation Army”.

The playing of the BBC Symphony Orchestra was exceptional, although this is probably not surprising for an orchestra so steeped in mastering the complexities of contemporary scores. If the tonality of Ruo’s music is not in itself difficult (some of the solos composed for both Song, and at the end of the opera for the transformed Gallimard/Butterfly, are exquisitely done in the manner of Puccini) then the rhythms he sometimes applies to his music are by no means easy. The string playing was often ravishing; brass were powerful and the timpani were explosive when needed. Carolyn Kuan conducted with great balance – orchestra, chorus and voices in perfect harmony: I suspect freedom from the pit offering a slightly better perspective for her.

How contemporary one sees M. Butterfly will vary depending on how one sees the tropes that affect us today. The play on which it is based and the opera were written in different times – it is the themes they touch on that have evolved. That evolution, of course, can be both progressive and regressive. The performances here were miraculous enough to remind us how attitudes have changed – and also as a mirror or corrective to Puccini’s own Madama Butterfly. But afterwards I did wonder, in a world with imperialism resurgent, gender choices restricted and cultural freedoms suppressed whether this opera is already a little dated.

Marc Bridle

M. Butterfly

By Huang Ruo, based on a libretto by David Henry Hwang

Cast and production staff:

Kangmin Justin Kim – Song Liling; Mark Stone – René Gallimard; Fleur Barron – Comrade Chin/Shu Fung; Kevin Burdette – Manuel Toulon/Judge; Charne Rochford – Marc; Ciara Hendrick – Agent No.1; Peter Davoren – Agent No.2

James Robinson – director; Kimberley Prescott – revival director; Allen Moyer – stage designer; James Schuette – costume designer; Christopher Akerlind – original lighting designer; Greg Emetaz – projections designer; BBC Singers; BBC Symphony Orchestra; Carolyn Kuan – conductor

Barbican, London, 25 October 2024

All photos: BBC/Mark Allan

M. Butterfly will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on Saturday 9 November.