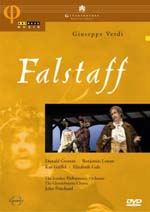

Giuseppe Verdi: Falstaff

Donald Gramm, Kay Griffel, Benjamin Luxon, Nucci Condo, Elizabeth Gale, Max René Cosotti,

Reni Penkova, Ugo Trama, Bernard Dickerson, John Fryatt

The London Philharmonic and The Glyndebourne Chorus, John Pritchard, conductor

ArtHaus 101 083 [DVD]

Years ago I remember reading a commentary on Verdi by a respected critic — Conrad L. Osborne — to the effect that most of early Verdi could have been written by Donizetti except for the first great success, Nabucco, that could have been written by Rossini. If one accepts that proposal, it would mean that Rossinian operas bracketed Verdi’s career, for surely Falstaff, at the very end, reflects the energy, elegance, joyousness and sophistication of Rossini from one end to the other.

ArtHaus Musik has released on one DVD a 1976 performance of Falstaff from the Glyndebourne Festival in a Jean-Pierre Ponnelle production conducted by John Pritchard. This opera has led something of a charmed life on recordings from various eras largely, I suspect, because its unique requirements and attractions have kept it in a kind of “festival” category of the repertory. Companies generally don’t approach Falstaff unless they have something special to contribute to its performance history. Hallmarks of the Glyndebourne production style have always included an ensemble approach to casting along with admirable musical and dramatic values–exactly the conditions under which Falstaff blossoms.

Ponnelle’s production is restrained and tends to downplay much of the traditional Falstaff “shtick.” There aren’t a great many props, furniture is kept to a minimum (there’s not the bourgeois display of wealth chez Ford that is the actual attraction for Falstaff) and he doesn’t encourage “comic bits” from his cast. Humor, and there’s much of it indeed, grows out of the situation at any given moment and the characters’ honest reactions to it.

The women are dressed almost exclusively in white. Quickly gets a black overdress, perhaps to indicate she’s widowed, while the younger women wear stylized fifteenth century gowns and wimples in pure white. The men are more detailed and more eclectic as to period. Dr. Caius sports a King Henry V haircut, Fenton looks far more early Tudor, while Ford alone sometimes suggests the late Elizabethan period in which Shakespeare set the story. Sir John himself often resembles an Edwardian gentleman, but that may well reflect the casting as much as the design choices.

Donald Gramm was surely among the suavest of Falstaffs vocally and physically. His phrasing is both elegant and refined, and he hasn’t been tricked out in too egregious a “fat suit.” He appears plump but far lighter in weight than several contemporary tenors and baritones seen on- or off-stage. In fact, this Falstaff for once seems a credible suitor to the ladies of Winsor, a genuine threat to Ford, and above all a nobleman in much more than mere title. That Gramm was really a bass is demonstrated clearly at the end of the “Honor” monolog when he takes an unexpected low option, but throughout he actually sings the role beautifully in a way that few ever have. The Gramm/Ponnelle Falstaff is unconventional and may put off some who love the traditionally disreputable crusty old rogue; but taken on its own terms it’s a successful alternate take on the character that’s most convincingly performed. British baritone Ben Luxon is handsome of both voice and bearing as Ford. Max René Cosotti is visibly more than a decade or so older than Fenton, the full dark beard not assisting the illusion of a teen-ager, but he sings quite nicely in a well-controlled, high and clear, slightly reedy tenor. . Ugo Trama is a solid Pistola; Bernard Dickerson a younger than normal, almost handsome but satisfyingly skuzzy Bardolph; and John Fryatt an appropriately annoying Dr. Caius.

The women are beautifully matched, their several ensembles flying along light as air. Kay Griffel’s Alice sets the tone with a richly colored full lyric soprano and winning personality. Reni Penkova does what can be done with Meg, and Nucci Condo, known as a comprimaria on a number of audio recordings from the period, turns in a ripely sung and acted Quickly with solid contralto underpinnings. For a modern audience, her noticeable resemblance to Nathan Lane may distract from — or possibly enhance — her most enjoyable performance. Elizabeth Gale is an enchanting Nanetta, lacking only a truly magical floated high piano to place her at the very top of recorded heap in the role.

Distinguished conductor John Pritchard has the lightness of touch required and draws strong work from the London Philharmonic, but he neglects to let the score breathe occasionally. Speed and precision seem to be his main goals and these are not irrelevant to Verdi’s score by any means. But there needs to be some contrast — Pritchard pushes ahead, at times almost mercilessly as when the “Pizzica, pizzica, pizzica, stuzzica” section of the scene tormenting Falstaff falls apart before it can even begin, because the women simply can’t get any more breath. It’s a very good job by any standards, but amid all the chiaro, there is some important scuro in Falstaff and Pritchard doesn’t always find it.

TV director Dave Heather’s video shots are among the finest I have encountered — a lovely mix of close-ups (avoiding a tiresome parade of “tonsil shots”) and pull-backs. He clearly understands that it’s important to allow two or three people to play a scene together in the frame without restlessly shifting from one to another constantly. You can elect subtitles in five languages and see clips from other Glyndebourne operas, a ballet and some orchestral concerts as a promotional bonus at the end of the program. This is a most attractive and very nicely produced Falstaff, an all too rare souvenir of the prematurely deceased Gramm in performance and at the very top of his form.

William Fregosi