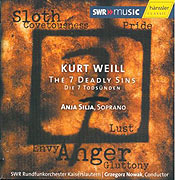

Kurt Weill: Die sieben Todsünden; Quodlibet op. 9 from the Pantomime “Zaubernacht” op. 4

Anja Silja, Julius Pfeifer, Alexander Yudenkov, Bernhard Hartmann, Torsten Müller,

SWR RO Kaiserslautern, Nowak

Hänssler Classic 93109 [CD]

A new recording of Kurt Weill’s (1900 – 1950) ballet chanté, Die 7 Todsünden (1933) featuring Anja Silja and the SWR Rundfunkorchestra Kaiserslautern and conducted by Grzegorz Nowak, has recently been made available in the U.S. on the Hänssler Classic label. Also included on the CD is Weill’s Quodlibet, opus 9 (1923) — an orchestral arrangement taken from his 1922 children’s pantomime, Zaubernacht.

Die 7 Todsünden is the product of Weill’s forced collaboration with Bertolt Brecht, from whom he had been estranged for nearly three years by the time the ballet was commissioned. Die 7 Todsünden is unusual in that it features prominently a vocalist and a dancer as two parts of the protagonist’s personality, as well as a male quartet and small dance roles. The ballet relates the adventures of the protagonist, a young woman named Anna, who must leave her home in provincial Louisiana to seek employment in the major cities of the U.S. in order to finance the building of a house for her family.

In the prologue we learn that Anna has a split personality, the practical side of which is portrayed by the singer (Anna I), while the more fanciful side of Anna — the part of her that dabbles in the seven deadly sins — is portrayed by a dancer (Anna II), who also has a few spoken line in the production. Anna’s family at home in Louisiana is represented by the male quartet, which in this recording is staffed by tenors Julius Pfeifer and Alexander Yudenkov, baritone Berhard Hartmann, and bass Torsten Müller.

Throughout the nine movements of the work — one for each deadly sin plus a prologue and an epilogue — we follow Anna’s struggles with sin and witness her family express their concern over her ability to avoid sinfulness. Ironically, neither Anna nor her family seem to worry about the seven deadly sins for religious or moral reasons; rather, the theme of the family’s arguments is that only by adhering to “the law” will Anna be able to earn a substantial amount of money. The libretto blatantly mocks bourgeois family values, and Weill’s musical settings of the text emphasize the hypocrisy of Anna’s family. For example, in the movement titled “Gluttony,” the male quartet sings a capella homophonic harmonies, imitating the sound of Lutheran chorales. Rather than conveying a message of avoiding gluttony in order to achieve moral soundness or entry in to Heaven, the family warns Anna not to be gluttonous, lest she gain weight and therefore lose her contract as a solo dancer in Philadelphia. Two men with revolvers, ostensibly at the behest of her employers, “help” Anna to maintain her weight at 110 pounds despite her fondness for muffins, cutlets, asparagus, chicken, and little yellow honey-buns.

Die 7 Todsünden was written for and premiered by Weill’s off-and-on-again wife Lotte Lenya in Paris at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. In a1955 recording of Die 7 Todsünden Lenya sings each of her movements down a fourth from their original pitch level — a musical decision made apparently without ever having discussed it with Weill. Lenya’s recording, part of an attempt to capture all Weill’s songs on record, set a precedent for later performances of Die 7 Todsünden so that in its published format, the score contains an appendix of Anna’s songs “for low voice,” this despite the composer’s lack of involvement in any such version.

Although she made this recording after a singing career of nearly five decades Silja gives a convincing performance as the young Anna I and Anna II, and she does so in the register at which Weill originally composed Anna’s songs. While a few notes at the top of her register seem to give Silja some trouble, her overall portrayal of the Annas is delightful. In interviews Silja has indicated that acting is as important to her as vocal technique, a philosophy that is apparent even on CD: this recording is full of energy and drama from the optimistic beginning all the way to the sardonic “Ja, Anna” at the end. Silja is ably supported by the male quartet whose performance highlight the pretentious nature of Anna’s family; this is especially true in “Covetousness,” a movement in which the family expresses their that Anna will not appear greedy to the extent that she ceases to exact money from her admirers. The quartet’s articulation is clear so no word is lost, and the hypocrisy of their concerns is immediately comprehensible.

In addition to the moving performances by the singers and the orchestra, the SWR recording can be recommended for its excellent sound quality. The warmth of Silja’s voice and the colors of the orchestra can be heard clearly throughout. The CD booklet contains notes in German that are (dubiously) translated into English, as well as the complete lyrics in both German and English and short bios for each of the performers.

Weill’s Die 7 Todsünden is just one of many modern works that deserves wider hearing. Quality recordings such as this Hänssler Classic CD will make access to these pieces easier and more enjoyable.

Megan Jenkins

CUNY The Graduate Center