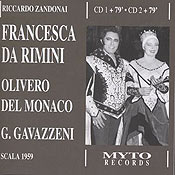

Riccardo Zandonai: Francesca da Rimini

Magda Olivero (Francesca); Pinuccia Perotti (Samaritana); Enrico Campi (Ostasio); Giampiero Malaspina (Giovanni la sciancato); Maro Del Monaco (Paolo il bello); Piero De Palma (Malatestino dall’occhio); Lydia Marimpietri (Biancofiore); Edda Vicenzi (Garsenda); Bianca Maria Casoni (Altichiara); Anna Maria Rota (Donella); Gabriella Carturan 4smaragdi); Angelo Mercuriali (Ser Toldo Berardengo); Dino Mantovani (Il giullare); Athos Cesarini (Il balestriere); Giuseppe Morresi (Il torrigiano); Rinaldo Pellizoni (un prigoniero)

Orchestra e Coro del Teatro alla Scala di Milano

Direttore: Gianandrea Gavazzeni

Live registration: 4th of June 1959

Myto 2MCD 051.303 [2CDs]

Strange to think that Magda Olivero has to thank Renata Tebaldi and Maria Callas for two of her best known live recordings. Tebaldi cancelled the famous Adriana Lecouvreur performances in Naples 1958 (Corelli, Bastianini, Simionato) and La Scala originally wanted Callas as Francesca da Rimini. Twice Olivero substituted and made the role so much her own that whenever one of these operas pops up in a conversation so does Olivero’s name. Contrary to Adriana, Francesca was not a staple in the soprano’s repertoire. She sang a few performances with Alessandro Ziliano and Tullio Serafin in Torino in 1940 and only returned to the role 19 years later for her second and last run of Francescas.

Nine years later she recorded three duets with Del Monaco for Decca/London; probably because there was some studio time left after their Fedora. Though the sound of the studio recording is far better (and there is no prompter as in the live La Scala) it cannot really compete with the live recording. The main difference is the marked deterioration of Del Monaco’s voice and style. But Decca’s Moritz Rosengarten was convinced that Del Monaco was the better seller than Carlo Bergonzi (for the 1968 Wally) or Bruno Prevedi (Norma of 1967 and Fedora of 1969). In the short term he was probably right but in the long term these Del Monaco-recordings are not the best money-makers in the back catalogue.

Even in 1959 most critics were not convinced that Del Monaco’s muscular style was right for Paolo the beautiful but this is without taking into account Zandonai’s heavy orchestration that often overwhelms a tenor like Prandelli in the Cetra-set. Moreover Del Monaco is here on his best behaviour. He respects the cantilenas and doesn’t chop up the line. There is no denying the intrinsic beauty and nobility of the voice and he almost leaves behind his disturbing sobbing habits which in his case resembled somewhat the whinnying of a horse (happens only once). He proves he can soften the mighty volume and shows in the duets how beautiful and tender he could phrase a mezza-voce when he wanted to. And the moment the music takes real heat there is of course that mighty column of sound. In short, this is probably one of his very best recordings together with Decca’s Fanciulla and the wonderful live Forza of 1953.

Nobody resembles Olivero so much as Magda Olivero. When one listens to her many live recordings (“Sono la regina dei pirate,” she once told me, though of course Gencer is a strong competitor), one is struck by the same tricks every time in every role; be it Francesca, Tosca, Minnie or Adriana. And of course the wonder of it is that she nevertheless gets away with it, convincing one half of opera lovers that this is among the greatest singing ever heard while the other half thinks that these are only cheap verismo mutterings. This reviewer belongs to the first category and he cannot have enough of the lady’s mannerisms: the strong vibrato when the voice is under pressure, the reducing of the voice to the extremely long held fil di voce, a mere thread of a voice, almost whispering; the emotional outbreaks, the excessive moans and sobs. But, and this is a big but, contrary to a lot of other verismo sopranos Olivero’s tricks are a means of expression, not technical deficiencies which must be hidden by vocal trickery. And, therefore, though one knows what to expect, one falls again under her magic spell from the moment Francesca appears. The voice moreover is at it’s most fresh as the lady at the moment of performances was only….49.

For those who think she always exaggerates her singing, there is a healthy reminder in the interesting four bonus tracks. At La Scala, national and international critics were to be found and, therefore, she always reined in; but, in a smaller provincial theatre like Modena in 1971, she could freely sing out, though maybe singing is not the correct word. In Medea we hear between sung notes some of the weirdest sounds I have ever heard: screaming, sobbing and a lugubrious kind of sprechgesang I never heard any singer use. It’s fascinating stuff for Olivero-lovers but I can imagine that most will think of it as over the hill.

Baritone Giampiero Malaspina (not the husband of Rita Orlandi Malaspina, that was bass Massimo) is a rather rough and ready Gianciotto, just employing a gruff big voice. The rest of the cast, however, is magnificent with tenor Piero De Palma as a fine menacing and threatening Malatestino. This is one of the most difficult roles for second tenor; but in the hands of a skilled performer, it can make a tremendous impression in the house and Di Palma uses his voluminous, though charmless, voice extremely well to characterize this unsympathetic toad.

La Scala casted all of the smaller female roles with singers who would go far like Lydia Marimpietra or Bianca Maria Casoni. The men are excellent too and they almost made up a roll call of those fine comprimario singers we all remember from many glorious EMI and Decca recordings in the fifties and sixties.

Gianandrea Gavazzeni and his marvellous orchestra is a little bit handicapped by the less than pristine sound which favours the singers. Therefore a lot of Zandonai’s formidable orchestration cannot be appreciated at its full value. As a consequence, some parts of the opera sound a little bit more boring than they actually are. But part of the blame lies with the authors (Zandonai and librettist Tito Ricordi), who were so intimidated by the fact they had the honour (very expensively bought) of using the divine Gabriele D’Annunzio’s poem, they had not the courage to delete a lot of superficial stuff. Zandonai played his score for the poet who was not very enthusiastic and who never attended one performance in the theatre. He missed a lot because Francesca da Rimini works far better in an opera house than on records. There are only seven recordings available and this is the best in my opinion, but the Spartan way it is presented in doesn’t make listening easier or more enjoyable. There is no libretto and it is a recording that needs one. There are no photographs of still existing buildings in Rimini and the fine castle of Gradara where the action unfolds (and where the erudite guide nevertheless didn’t know the opera when I visited).

Jan Neckers