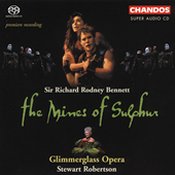

Until now, however, the work of this important company has not been featured on a commercially produced recording. Now that the precedent has been set for audio recording, perhaps some of their cutting edge productions can be recorded for DVD release as well. At any rate, this magnificent recording of Sir Richard Rodney Bennett and Beverly Cross’s little known opera The Mines of Sulphur sets the bar high for whatever releases might follow.

This is an extremely stage worthy work, which is probably why it will be a part of the New York City Opera’s 2005 season. Cross’s libretto, based on his earlier one-act play Scarlet Ribbons, is an eerie Gothic story of murder, moral decay, and characters of retribution who may or may not be real. Featuring a play-within-a-play that recalls the one in Hamlet – here, too, the consciences of the characters watching the play are troubled by it – and a delicious twist at the end, the work is memorably set in a decaying manor house in the West Country during a long dark winter. Cross creates realistic and / or enigmatic characters — one set of each — and writes a singable yet dramatically effective libretto. For the most part, the libretto could be produced successfully as a highly atmospheric and gripping play.

Such a production, however, would deprive us of Bennett’s score, and we would be the poorer for that. From his interest in jazz to his pursuit of the avant-garde at Darmstadt, Bennett has always been a composer and performer with a versatile range. But it is his experience with film scoring that perhaps served him best here. Although the first film he scored, a documentary about the history of insurance, probably did not stretch his dramatic insight, later scores, such as that for Stanley Donan’s 1958 classic Indiscreet, did. By the time he began working with Cross’s libretto, he knew how to create atmosphere and suggest character with deft and skillful gestures, and his insight into, and expressive writing for, characters are talents he shares with the best composers for the operatic stage. Reviewing the 2004 Glimmerglass Opera production for the New York Times, Johanna Keller wrote, “The musical language could be called loose serialism: atonal, but with recurrent melodic fragments and fleeting tonal centers.” The orchestral scoring is evocative and atmospheric as well as character-specific. The duet at the end of the original act 1 – more about the act divisions in a moment – for Rosalind (mezzo) and Jenny (soprano) is a wonderful, haunting, and prescient scene for the two women, and it is masterful writing for the voice as well as exemplary text setting. And, later, Rosalind’s “I want to leave this house” is one of the most effective passages in the work. The scene preceding the women’s duet, in which the troupe of actors set up and pointedly but playfully banter with each other, is terrific character-specific writing in which we quickly get a good sense of whom each of the actors is. It invites good singing-acting.

In this performance, the work for the most part gets the singing-acting it deserves. This recording was drawn from live performances, so we must remember that what works in the theater does not always transfer with equal success to a recording: we are only getting one dimension of the performance. While Beth Clayton’s sung performance as Rosalind is gorgeous and dramatically convincing, for instance, her spoken lines are less so. Caroline Worra as Jenny, the mysterious actress with a potent secret to share at the end, is very good as well, although she must deal with one of Bennett’s few problematic pieces of writing. At the end of her ballad about a troupe of actors, near the end of the opera, she must sing the important line, “They were infected with the plague,” which ends on a very high note and which is unintelligible. Bennett had to decide between musical and literal expressivity, and the former won. However, with the use of supertitles at the NYCO, everyone should get both effects. James Maddelena is tremendous as always; he could give diction lessons to about anyone singing in English today, and he executes that diction with a baritone voice of sustained and notable beauty. Brandon Jovanovich uses his powerful tenor voice well, and Kristopher Irmiter is convincing as Braxton, the landowner killed early in act 1, and the actor-manager of the acting troupe. The doubling of these two roles is required by the script, and it may tell us something about the strange appearance and disappearance of the actors. Are they even real? Finally, I must mention Michael Todd Simpson, who has several extended scenes as Tooley, one of the actors. Mr. Simpson, who possesses a strong rich baritone voice and who handles the acting chores of his two monologues with impressive craft, was a member of Glimmerglass Opera’s Young American Artists Program. He unfortunately will not be repeating the role at the NYCO. I’m sure whoever is engaged will be good, perhaps even as good as Mr. Simpson. But I doubt if he is better.

With the permission of Bennett, the three act opera is presented in two acts. The division between acts 1 and 2 bothered me. It seemed ill advised to interrupt the play-within-the-play. But doing away with the original break between acts 2 and 3 is a decided improvement, so I guess it works out even. (And makes for a somewhat shorter evening, although the work is not particularly long.)

Stewart Robinson, who has a keen sense of the work’s dramatic structure, conducts the performance. If at times the orchestra verges on overpowering the singers, we must remember that this is taken from live performances; it is not ever a threat to the singers. The orchestra plays for Robinson with brilliance and produces the stunning palette of colors required by Bennett’s orchestrations. Bennett should be grateful his work is in such gifted hands.

The recorded sound is outstanding, thanks to producer Blanton Alspaugh and sound engineer John Newton. The two CD set comes attractively packaged with substantial notes by the conductor.

Anyone able to see the work in New York should make a point of doing so. It is richly theatrical and, like all opera, is meant to be experienced in the theater. With many in this cast repeating their performances, it should be a memorable evening. For those unable to make it to Lincoln Center, however, this is an important recording of an opera that deserves a wider audience. Don’t miss it if you care about modern opera.

Jim Lovensheimer, Ph.D.

Blair School of Music, Vanderbilt University