Flimm’s magical and creative stage direction seldom flags, and Harnoncourt’s Concentus Musicus Wien drives the whole mad, not to say occasionally maddening, pantechnicon along at a great pace and with admirable musical sensibility.

The pain came with equal regularity however. An interesting point about these last great flowerings of young Henry Purcell’s genius, so soon to be snuffed out, is that they were almost an anachronism when they first reached the stage of the Queens Theatre, Dorset Garden, London in 1691. Italian opera was approaching as if on a flood tide. Today it is difficult for an audience raised on either that later opera seria or mainstream romantic opera to grasp either the idiom of English music theatre in the 1690s or accept its artistic context - such as might be gleaned from a quote in the Gentleman’s Journal of 1692 “…experience hath taught us that our English genius will not relish that perpetual Singing,” Those said Gentlemen preferred what we might call today “mixed media” with plots that were not only true to life but sported humour, slapstick and sensational effects. And this Salzburg production, in the final analysis, whilst trying to achieve relevance and an understandable context by updating this template from the 1690’s, is let down by artistic incoherence and muddle. The fun, the spirit and the comedy of what Harnoncourt has described as the “first musical in history” doesn’t quite make up for some pretty dire interpretative decisions.

So if not an “opera” at all, then or now, what is it? It’s a play, with words by Dryden, which has musical tableaux which intersperse the main blocks of story-telling dialogue. The drama, acted and spoken by professional actors, tells the story of enemy kings Arthur and Oswald, fighting for English power and the heart of a princess, Emmeline, who happens to be blind. Each is supported by their own “magical helpers” - Merlin (a slightly ineffectual English dandy) and Grimbald (a most unpleasant piece of work) - and accompanying spirits. There is no doubt who are the “goodies” and “baddies” and which side this jingoistic libretto takes. It also just so happens that the music that was written to accompany the piece at the theatre was some of the best truly indigenous English song writing ever to bloom on a London stage, even to this day. And as in Purcell’s time, both the actors and singers are on stage together and often “duplicate” each other with matching costumes - an idea that one soon assimilates without too much trouble, although the camera close ups of the DVD obviously make this deliberate deceit entirely transparent.

The story is a gift for any creative director with the full panoply of 21st century stage effects at his disposal, and Flimm makes admirable use of the unique setting: the Summer Riding School in Salzburg, with its baroque form and intriguing balustraded arcades, built in 1693. The excellent orchestra is housed in a sunken area around which the stage continues, allowing the actors and singers to occasionally encompass the musicians and, from time to time, even draw them and their conductor into proceedings. This allows nice little comic business: the rather august head of Nikolaus Harnoncourt being carefully wrapped in a woolly bobble cap against the cold of the Frost Scene; a terrified fairy seeks shelter amongst the bassoons… and so on. Video screens in the “sky”, flying lines for the fairy spirits, trap-doors for the almost Wagnerian evil-doers on the Saxon side - it’s all there, and you’d have to be a very miserable person not to respond with a smile, at least once per scene.

However, as was reported at the time of the stage premier, the successes must be weighed against some unfortunate decisions. Dryden’s story may not be exactly great drama - it’s been described as “tub-thumpingly patriotic” and you’d be hard pushed to deny that. But, and it’s a big but, the language he used to do the tub-thumping was elegant, witty and often beautiful. Here, presumably for the sake of Salzburg success, all the English drama is translated into German, with almost entirely German or Austrian actors. What was wit with a lighter touch becomes heavily obvious; what was English seaside-style slapstick becomes Bavarian bier-keller. Vowel-curdling diction in mock-mittel-european-horror-flick style does Dryden no favours, and it is with huge relief that one hears the first melodic lines of English when the singers (excellent in name, if uneven in performance on this showing) take the stage.

One is reminded of a kind of “beauty and the beast” scenario. On the DVD, of course, one has the convenience of subtitles - so at least the viewer at home can have the story explained in English, or whichever language is preferred. Not that this helps particularly with all the local in-jokes and modern Austro/German political references which attempt to make relevant some of the original humour - always high risk for an internationally-released production.

Yet, happily, it is the music of Purcell that saves the day every time - tune after tune delights the ear and kindles memories from a hundred earlier hearings in different, incomplete contexts: “First Act Tune”, “How blest are shepherds”, the “Chaconne”, “’Tis Love” and “Trumpet Tune”, the list goes on and on. To at last hear them in the way that London audiences did in 1691 is a treat indeed.

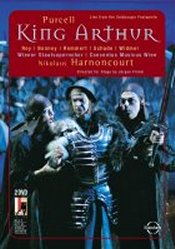

The voices are certainly starry: Barbara Bonney, Michael Shade, Isabel Rey, Oliver Widmer and Birgit Remmert and you have to applaud the way they throw themselves (sometimes literally) into the story even if some are hard pressed to produce their best sounds in some difficult situations and eccentric costumes. The sight of a well-built Michael Shade throwing himself around the stage, stand- mic clasped to mouth, legs akimbo, in a hilarious spoof on an ageing rocker howling out “Your hay, it’s mowed” in the form of a torch song to his adoring fans, won’t be easily forgotten.

Less successful was Bonney’s rendition of the lovely, seraphic “Fairest Isle, all Isles Excelling” towards the end of the performance - not approaching the silvery perfection of her CD recording and somewhat rushed and uncomfortable in execution. The famous “Frost Scene” was played for humour with a chorus of neatly-choreographed penguins (what else?) in support, even if Oliver Widmer’s rather clunky baritone made heavy arctic weather of the famously-extreme stuttering notes.

Yet, despite this and an overall problem with maintaining all the disparate threads of action, chorus, music, song, video and stage machinery, “King Arthur” is still a brave attempt to re-vivify the largely lost art form of English Restoration music-drama in something like its original concept - and I’d recommend it to anyone who loves the music of Purcell, as long as they have a capacity to forgive as well as to applaud.

© Sue Loder 2005