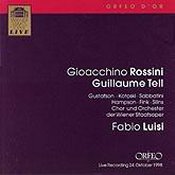

Perhaps the opera’s unflattering depiction of the Austrians as invaders and repressors of the Swiss people had something to do with the opera’s long absence from the Viennese repertoire. More likely, the extraordinary demands this epic work places upon the soloists, chorus, orchestra, and yes, the audience, were the main culprits. In any event, the Vienna Staatsoper did itself proud and Rossini’s masterwork justice with the 1998 revival. We are fortunate to have it documented in this recent Orfeo release.

Although the opera is named William Tell, the greatest challenge in staging the opera rests with the leading tenor role of Arnold. Written for the legendary French tenor Adolphe Nourrit, Arnold demands a singer who can sing with both heroic power and ardent tenderness, all the while negotiating a superhuman tessitura that seems to encompass countless high Cs. Arnold is, quite simply, one of the most difficult roles in the entire tenor repertoire.

In the Staatsoper production, Arnold is the Italian tenor Giuseppe Sabbatini. For the most part, he is superb. His French diction is quite excellent, the voice has both a penetrating and attractive timbre, and the many high notes are always brilliant, secure, and masterfully integrated with the rest of his vocal production. Sabbatini’s singing demonstrates an admirable combination of passion and elegant phrasing, as well as the ability to scale back dynamics to great musical and dramatic effect, as in the Act II duet with Mathilde and the second verse of his great aria, “Asil héréditaire.” On the negative side, Sabbatini often seems unable to maintain a true legato, substituting aspirates instead. And the voice lacks a basic heroic quality that I prefer in this role. But Sabbatini’s contribution, particularly in the context of the tightrope walk of an in-performance recording, is really quite extraordinary.

Likewise, Thomas Hampson’s William Tell is a great asset. As with Sabbatini, Hampson’s French is quite fine. Apart from some difficulty with the lower notes of Tell’s vocal writing, Hampson is in secure and impressive voice. I recommend this performance to those who view Hampson as an overly mannered singer. Here, he sings with the kind of directness and heroism that beautifully matches the character of the Swiss patriot. Hampson is also not afraid to abandon beautiful tonal production when the dramatic situation requires, as in the Act I duet with Arnold, or in his dispatch of the villain, Gessler. On the other hand, Hampson’s heartfelt and gorgeously sung “Sois immobile” is one of the highlights of the performance.

Soprano Nancy Gustafson sings with laudable vocal beauty and security. She also convincingly projects Mathilde’s tender, regal, and heroic aspects. Like Hampson, Gustafson is not totally secure in the lowest portions of the role. But overall, she is a major factor in the success of this production.

The many subsidiary roles are cast with strength. The contributions of the Vienna State Opera Chorus and Orchestra are outstanding, both in terms of precision and tonal beauty. The horn playing in particular is absolutely stunning.

No doubt much of the success of this William Tell rests with conductor Fabio Luisi, who leads a performance that has tremendous forward propulsion, but which never gives short shrift to this amazing score’s many details and beauties. Many have commented on how Rossini’s final opera paved the way for the course of much of 19th-century French and Italian opera. But the masterfully paced and brilliantly executed rendition of the opera’s stunning finale also brought to my mind (for the first time) the great symphonies of Anton Bruckner as well. What a remarkable work this is!

The in-performance recording features a superb balance between stage and pit, a wonderful sense of the hall’s ambience, as well as a fair amount of stage noise and well-deserved applause. All of this adds to the sense of a very special occasion, indeed.

The early-70s EMI studio recording with Gabriel Bacquier, Nicolai Gedda, and Montserrat Caballé, conducted by Lamberto Gardelli, remains my preferred version of Guillaume Tell. I also have a weak spot for a 1979 Geneva performance in Italian, conducted by Anton Guadagno. It documents a fearless and hair-raising (if occasionally rough) performance of Arnold by Franco Bonisolli. It is available as highlights from Gala, and issued complete by the Opera Magic’s label.

The Orfeo release has no libretto, just a listing of cast and music tracks, an essay on the opera and Staatsoper production, and cast photos. Still, this performance has numerous qualities that make it a major addition to the Tell discography, despite cuts in this mammoth score. As a great fan of this opera, I’m sure I’ll return often to this Orfeo Guillaume Tell.

Ken Meltzer