Women and children and even men had fun singing. In groups! In public! Instead of playing dartball or scrapbooking! Today in 2006 it seems astounding that people enjoyed being part of ensembles rather than teams—a word I’m sure the gods must flee in horror, it’s become so ubiquitous and at the same time so meaningless; everything in America works in “teams” and uses “teamwork” nowadays, to the neglect of collaborative techniques that entail more than reliving the recesses of our childhoods.

When I was a kid, not a century or so past, the Southern Illinois town I lived in had a Cultural Society that put on an annual Christmas concert as well as top-notch productions of musicals and other concerts. I currently live in a small Midwestern city (population 20,000, about the same size as the town I grew up in), and public choral singing is pretty nonexistent. We have a Lutheran Men’s Chorus, average age about 50, that sings at Lutheran functions and the Mayor’s Good Friday Prayer Breakfast. But that’s the extent of public choral singing here in the Heartland. Churches have their various choirs, whose numbers hardly compare to those even 15 or 20 years ago. A few still stage annual Easter spectaculars (“The Living Cross”), but you don’t find the John Peterson or Bill Gaither Christmas and Easter cantatas that church congregations used to enjoy.

Back in those years of yore when everything was bathed in a golden glow, even on those days when our grandparents trekked to school through five feet of snow (and lived to tell us about it, over and over), another now almost forgotten activity was memorization and recitation. Memorization of more than just the states and their capitals or the most common chemical elements and their symbols. Poems. Long poems. Poems of tens if not hundreds of lines. “Listen my children and you shall hear,/Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.” “This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks, ...” And then they had to turn around and recite them in front of their parents and, worse, sniggering brothers and sisters in convocations! No wonder the education czars don’t have children do that anymore. It traumatizes them. Rote memorization is bad. Poetry is bad. (Though what is rap if not nineteenth-century four-square poetry urbanized?) And memorization takes away from time better spent learning to take tests to meet the demands of the No School Administrator Left Behind Act.

It’s strange, though. Do those of us who had to sing in public concerts several times a year as kids have bad memories of it? I don’t. Every so often I’ll think of some piece I sang a few decades back (“O Star [the fairest one in sight]” from Randall Thompson’s setting of the Robert Frost poem), or I’ll hear a song on the radio that we sang in my high school chorus (the Beatles’ “When I’m 64”). I still love Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast, which we did in college. What a fun piece! I don’t think I ever had to memorize long poems—species and genus and family and on up Linnaeus’s ladder was my challenge—but one of my parents still comes out with “Little Orphan Annie’s come to our house to stay” every so often, and they’re none the worse for having had to have learnt it.

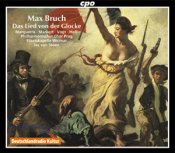

So on to the proper subject of this review, Max Bruch’s Das Lied von der Glocke (The Song [or Lay] of the Bell; 1878). Bruch, best known for his violin concerto, Scottish Fantasy for violin and orchestra, and Kol Nidrei for cello and orchestra, lived an amazingly long time for a nineteenth-century composer, from 1838 to 1920. He tried his hand at opera as a young man, but abandoned the genre at the age of only 34, with Hermione, based on Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. Bruch continued in his secular oratorios his penchant for choosing not exactly lightweight subjects to set to music: Odysseus, Achilles, Arminius (a.k.a. Hermann, victor of the battle against the Romans at the Teutoburg Forest). Of course, in the nineteenth century, these mythical and legendary heroes were well known to everyone through that rote memorization—oftentimes in the original Greek—that we’ve now decided is such a waste of effort. Young people recite their favorite rap songs with gusto though; perhaps rhymed learning and remembrance might be advantageous in an evolutionary sense?

Schiller’s poem was a favorite of 19th-century German pedagogues, all umpteen hundred lines committed to memory by countless squirming German youths (better this than the poet’s diatribe against Christianity “Die Götter Griechenlands”). Compared to it, Longfellow’s poems are lightweight stuff indeed! Written in 1799, the year Schiller moved to Weimar, the poem connects the casting of a great bell with stages in human life in the poet’s “sentimental,” middle-class worldview. It was already well known by the time of Schiller’s death in 1805, and by the middle of the century it was used to help justify German unification. Nowadays readers are probably snoozing by the time they get to admonitions to die Jugend like “Der Wahn ist kurz, die Reu ist lang” (Illusion is brief, but Repentance is long). But, with echoes of his more familiar “An die Freude” set by Ludwig van, Schiller summons up a stirring finale where the bell soars upward to the heavens, its first notes heralding Peace.

Bruch had an ear for a good melody, but he was never the most original composer. Bits of this oratorio sound like Wagner, other passages like Brahms or Mendelssohn. With the galumphing tympani and sprawling orchestral forces coming close to being blown off the stage by the brass section, we hear the Mahler 8ths to come. The forces here, appropriately centered around the Staatskapelle Weimar, give the work a competent performance in the best conservatory-trained Central European tradition. I’m not sure it’s possible to hear a brilliant performance of Bruch’s oratorio, but listeners won’t find anything here that’s offsetting.

So did the Prague Philharmonic Choir and the soloists in this recording, or the singers who premiered the work in the 1870s and the other choral groups who performed it in the following decades, really enjoy learning this music and singing the slightly ponderous text, or—in the case of those long-ago singers—did they just not have anything more exciting to do on those gas-lit, five-foot-snowdrift winter evenings, and this was their idea of something to do and a way to get out of the house? I maintain that they really did see it as fun, as we might see a playing a video game, but also enjoyable (not the same as “fun”), and more important, as uplifting. For listeners, performances weren’t just another night in your subscription series. Learning music, and memorizing long poems, was a mental challenge, not mental drudgery. It was good preparation for other academic activities that hopefully would bring material success in business or industry. Choral singing and rote memorization took Discipline. These weren’t hobbies or sports for individuals and star players, scrapbooking the family’s year in pictures and newspaper clippings or winning the local men’s softball trophy. An ensemble is fundamentally different from a team; it involves a degree of constant collaborative feedback that, to my admittedly couch potato point of view, blows “teamwork” out of the water.

Our children probably wouldn’t be scarred (or scared) for life if they were expected to memorize hundred-line poems. Learning memorization tricks and techniques would help them master other analytical skills. I won’t argue that the current cult of the individual, doing your own thing and making your first million as young as possible, hasn’t had its benefits (at least equaled by its drawbacks), but perhaps if more children were to sing in school or church choruses learning large-scale pieces like Bruch’s oratorio (maybe even required to memorize the words), they would learn to listen to each other, something that is fast becoming a bygone skill, as seen daily on C-SPAN. The Duke of Wellington famously remarked that the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playfields of Eton. The future battles of Baghdad and the economic battles of Shanghai and Calcutta are less likely to be won on the playing fields of the Lakers and the Steelers and the Cubs than on the playing fields of the mind and through community-focused ensemble-work.

David E. Anderson