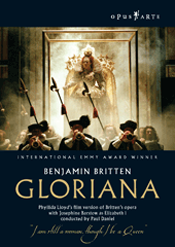

Britten’s opera focuses primarily on the character of the aging Queen Elizabeth I. The plot may

revolve around her feelings for the Earl of Essex, but Britten knew that most audiences would

know the story already : his aim was to explore why Elisabeth needed to keep up her image of

invulnerability. In the first scene, the Earl of Essex sings about a “chess game” in which the goal

is to win the queen. This Queen has to keep ahead of the game, constantly, through stratagem

and the illusion of invulnerability. Thus the stage action is woven with scenes from “behind the

scenes”, creating the effect of illusion within illusion.

Like the Queen herself, Barstow the actress is under pressure to perform. In the opening scene,

where she looks wearily into the mirror in her dressing room, while listening to the overture. It’s

very moving. Not all singers make good actresses. Barstow, though, is exceptionally good.

She’s so convincing that you forget, for a moment, that this, too, is illusion and stagecraft. Her

whole performance is a masterclass in opera characterisation, and worth studying for its own

sake. This Elizabeth is no fool, but watchful and tense, like a coiled spring. Hence the sharp

delivery and attack, and the bristling, sharp edge to the voice. When the Queen steals her rival’s

dress and dances in it, Barstow spits out her lines savagely, bringing out the menace that

underpins the elaborate party games at Court. When Essex breaks into the Queens room and

finds her unadorned and bald, Barstow’s very silence is moving. When she dismisses him, her

voice wobbles, “Go, Robin, go” in an intense mixture of conflicted emotion, before she crumbles,

the camera mercifully switching to long shot. It makes the “dressing scene” which follows all the

more poignant. Her white makeup is lit so her face looks like a death mask. Later, when she

assures Lady Essex that her children will be spared, her voice trembles with tenderness, “Frances,

a woman speaks”. Seconds later, her voice becomes shrill with anger as she scolds Lady Rich,

but when she’s signed the death warrant, her face contorts into a terrifying, wordless expression.

Film creates special new opportunities. For example, in the “Mortua”, when the Queen finally

faces her mortality, there are long silences which would not work on stage or recording. Here

though, the camera dwells on Barstow’s face which registers intense emotion. Sound, as such, is

unnecessary. When she does sing, weakly, the song she and Essex had playfully sung long ago,

she sing so quietly and tenderly that the impact would otherwise be lost. Similarly when she’d

earlier explained her love for her nation, the camera pans the balconies in the opera house,

backstage attendants and so on, as if all the world were listening to those noble, ringing words.

Just as the film draws out the effort the Queen makes to remain in control, the film shows how

much work goes on behind the scenes of a production. Recordings alone can sometimes break

the link between listener and performer, so sometimes people focus on recording values rather

than on artistic creation. This film is an excellent reminder that it is people who make opera and

that it isn’t easy work !

Musically, of course, this is very good, for Opera North has very high standards indeed. Britten’s

score itself adapts early English music forms, weaving them into the whole, just as the film itself

expands the basic opera. Early English music and poetry meant a great deal to the composer and

this is one of the longest works in which he explores it. Therefore Daniels delineates these

aspects of the score very clearly, because they, too, are an integral part of the multi-layered,

shape-shifting whole. If the courtly dances are somewhat on the fast side, that relates to the

narrative — the Queen deliberately tests the courtiers to their limits by making them dance and

sing at a furious pace ! Daniels also has the measure of Britten’s acerbic dissonances which,

throughout the opera add to the edgy tension in the drama. This opera has never been “popular”

because its uncomfortable idiom seems at odds with the opulent setting, but that was Britten’s

point. This is a powerful film, and completely unique.

Anne Ozorio