Yet both stagings

had in common a deep respect for — and knowledge of — the original

dramatic concept and the underlying music, something increasingly rare

nowadays.

In fact, both young directors have one more common feature, since their

fathers Duilio Courir and Claudio Abbado rank among Italy’s shining stars

— in music criticism and in conducting, respectively. Being born into the

trade at such top levels may rather work as a hindrance, at least when a

budding professional is determined to build his/her own independent career

without relying on family connections. Ms Courir is one such case, having

debuted in opera direction relatively late in 1994 with an appreciated

staging of Vivaldi’s Tamerlano at Verona’s Teatro Filarmonico,

at the age of 30 and after diverse experiences in spoken drama.

Actually, most of her educational curriculum pointed towards opera. The

10-year girl who used to sing in the children’s choir at La Scala grew up

to study music at the Scuola Civica di Milano, alongside humanities, theater

and musicology at the State University in the same town. For a period, she

even took singing lesson from the vocal scholar Rodolfo Celletti, also

attending the masterclasses held at Fiesole (Florence) by Walter Blazer, the

well-known teacher from the Manhattan School of Music. As to direction, she

apprenticed with such masters as Dario Fo and Luca Ronconi — but

particularly Egisto Marcucci, noted for his rigor, discrimination of, and

in-depth research on, texts, whether sung or spoken.

Actually, most of her educational curriculum pointed towards opera. The

10-year girl who used to sing in the children’s choir at La Scala grew up

to study music at the Scuola Civica di Milano, alongside humanities, theater

and musicology at the State University in the same town. For a period, she

even took singing lesson from the vocal scholar Rodolfo Celletti, also

attending the masterclasses held at Fiesole (Florence) by Walter Blazer, the

well-known teacher from the Manhattan School of Music. As to direction, she

apprenticed with such masters as Dario Fo and Luca Ronconi — but

particularly Egisto Marcucci, noted for his rigor, discrimination of, and

in-depth research on, texts, whether sung or spoken.

Courir’s latest opera staging, Verdi’s Il trovatore,

generally counts as popular fare; however, her reading thereof appears

unconventional, aristocratic and upstream — starting right from its

location: an outdoor arena at Vigoleno, soaring high on the green hills

between Parma and Piacenza in the Po Valley. The castle and hamlet of

Vigoleno, built in its present form during the 1390s, was a meeting point for

the culturati during the 1920-30s. Gabriele D’Annunzio, Max Ernst, Jean

Cocteau, Artur Rubinstein among Europeans, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks

and Elsa Maxwell from the USA; all were guests here at the duchesse

de Grammont’s, born princess Maria Ruspoli (incidentally: from the same

family who offered lavish hospitality to young Handel in Rome).

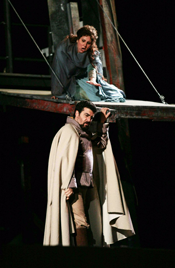

The castle itself, with its towers, battlemented walls and gates, provided

a hyperrealistic backdrop to a plot set in no less than two castles in Spain

during roughly the same age: Aljaferia and Castellor. Light years far from

the current trend of European opera direction, where the setting would be

typically a dilapidated industrial plant, a garage, a gay bar, a spacecraft

or whatever else. Tall wooden boards, all crooked and scorched, served as a

camouflage for covered bays were patrols were doing their rounds. A

drawdbridge suspended over a dark gulf was alternatively the springboard

whence Manrico was expected to launch his treacherous high Cs in “Di quella

pira” and the stairway plunging into the dungeon “where the State

prisoners languish”. Less blacksmiths than dyers, the Gypsies hanged out

the garish product of their industry from virtual battlements mirroring the

real ones, or celebrated and sung by torchlight while squatting down in

circles around certain disquieting cauldrons. Tribal and gloomy with a shade

of the Orient — such was the medieval Spain conjured up by Courir and her

team: set designer Guido Fiorato, costume designer Artemio Cabassi and

Fiammetta Baldiserri in charge of lighting.

The castle itself, with its towers, battlemented walls and gates, provided

a hyperrealistic backdrop to a plot set in no less than two castles in Spain

during roughly the same age: Aljaferia and Castellor. Light years far from

the current trend of European opera direction, where the setting would be

typically a dilapidated industrial plant, a garage, a gay bar, a spacecraft

or whatever else. Tall wooden boards, all crooked and scorched, served as a

camouflage for covered bays were patrols were doing their rounds. A

drawdbridge suspended over a dark gulf was alternatively the springboard

whence Manrico was expected to launch his treacherous high Cs in “Di quella

pira” and the stairway plunging into the dungeon “where the State

prisoners languish”. Less blacksmiths than dyers, the Gypsies hanged out

the garish product of their industry from virtual battlements mirroring the

real ones, or celebrated and sung by torchlight while squatting down in

circles around certain disquieting cauldrons. Tribal and gloomy with a shade

of the Orient — such was the medieval Spain conjured up by Courir and her

team: set designer Guido Fiorato, costume designer Artemio Cabassi and

Fiammetta Baldiserri in charge of lighting.

Within that (basically reliable, yet never archaeologic) framework, bodies

shaped their passions in the mould of unavoidable melodrama. The lecherous

Count attained by bitter qualms of conscience in the end; Leonora a

compassionate Madonna in light-blue train; Manrico a greyish bachelor,

moonstruck by misfortune and clearly a noble born-looser. Azucena towered

throughout in her fiery red gowns, as young and sexy as possible. Rather than

Manrico’s mother, she looked like his paramour, while a manly Ferrando kept

jerking her with ill-conceived desire. Side characters, nuns, warriors,

courtiers and sundry extras navigated smoothly, then suddenly disappeared

behind the boards. Perfect clockwork and grand opera on a grand scale, though

with limited means.

Within that (basically reliable, yet never archaeologic) framework, bodies

shaped their passions in the mould of unavoidable melodrama. The lecherous

Count attained by bitter qualms of conscience in the end; Leonora a

compassionate Madonna in light-blue train; Manrico a greyish bachelor,

moonstruck by misfortune and clearly a noble born-looser. Azucena towered

throughout in her fiery red gowns, as young and sexy as possible. Rather than

Manrico’s mother, she looked like his paramour, while a manly Ferrando kept

jerking her with ill-conceived desire. Side characters, nuns, warriors,

courtiers and sundry extras navigated smoothly, then suddenly disappeared

behind the boards. Perfect clockwork and grand opera on a grand scale, though

with limited means.

The junior singing company was enough well-matched (a crucial requirement

for Il trovatore), with baritone Claudio Sgura getting the best

applause for both his vocal qualities and sensitive acting. Rachele Stanisci

(Leonora) has her strongpoint in agility, as Laura Brioli (Azucena) in sheer

power; yet a more restrained vibrato during their forte passages would not

spoil. As Manrico, the experienced tenor Renzo Zulian sounded strangely

fatigued and/or unhappy with his upper register, probably due to a

last-minute stand-in for an ailing colleague. Orchestra Filarmonica Toscanini

and Coro del Teatro Municipale di Piacenza, both emerging ensembles, were led

by Massimiliano Stefanelli with unrelenting pulse, despite a troublesome

acoustic environment. Outdoor venues have their pros and cons, particularly

during a windy early Summer as this is proving to be.

Carlo Vitali

Actually, most of her educational curriculum pointed towards opera. The

10-year girl who used to sing in the children’s choir at La Scala grew up

to study music at the Scuola Civica di Milano, alongside humanities, theater

and musicology at the State University in the same town. For a period, she

even took singing lesson from the vocal scholar Rodolfo Celletti, also

attending the masterclasses held at Fiesole (Florence) by Walter Blazer, the

well-known teacher from the Manhattan School of Music. As to direction, she

apprenticed with such masters as Dario Fo and Luca Ronconi — but

particularly Egisto Marcucci, noted for his rigor, discrimination of, and

in-depth research on, texts, whether sung or spoken.

Actually, most of her educational curriculum pointed towards opera. The

10-year girl who used to sing in the children’s choir at La Scala grew up

to study music at the Scuola Civica di Milano, alongside humanities, theater

and musicology at the State University in the same town. For a period, she

even took singing lesson from the vocal scholar Rodolfo Celletti, also

attending the masterclasses held at Fiesole (Florence) by Walter Blazer, the

well-known teacher from the Manhattan School of Music. As to direction, she

apprenticed with such masters as Dario Fo and Luca Ronconi — but

particularly Egisto Marcucci, noted for his rigor, discrimination of, and

in-depth research on, texts, whether sung or spoken. The castle itself, with its towers, battlemented walls and gates, provided

a hyperrealistic backdrop to a plot set in no less than two castles in Spain

during roughly the same age: Aljaferia and Castellor. Light years far from

the current trend of European opera direction, where the setting would be

typically a dilapidated industrial plant, a garage, a gay bar, a spacecraft

or whatever else. Tall wooden boards, all crooked and scorched, served as a

camouflage for covered bays were patrols were doing their rounds. A

drawdbridge suspended over a dark gulf was alternatively the springboard

whence Manrico was expected to launch his treacherous high Cs in “Di quella

pira” and the stairway plunging into the dungeon “where the State

prisoners languish”. Less blacksmiths than dyers, the Gypsies hanged out

the garish product of their industry from virtual battlements mirroring the

real ones, or celebrated and sung by torchlight while squatting down in

circles around certain disquieting cauldrons. Tribal and gloomy with a shade

of the Orient — such was the medieval Spain conjured up by Courir and her

team: set designer Guido Fiorato, costume designer Artemio Cabassi and

Fiammetta Baldiserri in charge of lighting.

The castle itself, with its towers, battlemented walls and gates, provided

a hyperrealistic backdrop to a plot set in no less than two castles in Spain

during roughly the same age: Aljaferia and Castellor. Light years far from

the current trend of European opera direction, where the setting would be

typically a dilapidated industrial plant, a garage, a gay bar, a spacecraft

or whatever else. Tall wooden boards, all crooked and scorched, served as a

camouflage for covered bays were patrols were doing their rounds. A

drawdbridge suspended over a dark gulf was alternatively the springboard

whence Manrico was expected to launch his treacherous high Cs in “Di quella

pira” and the stairway plunging into the dungeon “where the State

prisoners languish”. Less blacksmiths than dyers, the Gypsies hanged out

the garish product of their industry from virtual battlements mirroring the

real ones, or celebrated and sung by torchlight while squatting down in

circles around certain disquieting cauldrons. Tribal and gloomy with a shade

of the Orient — such was the medieval Spain conjured up by Courir and her

team: set designer Guido Fiorato, costume designer Artemio Cabassi and

Fiammetta Baldiserri in charge of lighting. Within that (basically reliable, yet never archaeologic) framework, bodies

shaped their passions in the mould of unavoidable melodrama. The lecherous

Count attained by bitter qualms of conscience in the end; Leonora a

compassionate Madonna in light-blue train; Manrico a greyish bachelor,

moonstruck by misfortune and clearly a noble born-looser. Azucena towered

throughout in her fiery red gowns, as young and sexy as possible. Rather than

Manrico’s mother, she looked like his paramour, while a manly Ferrando kept

jerking her with ill-conceived desire. Side characters, nuns, warriors,

courtiers and sundry extras navigated smoothly, then suddenly disappeared

behind the boards. Perfect clockwork and grand opera on a grand scale, though

with limited means.

Within that (basically reliable, yet never archaeologic) framework, bodies

shaped their passions in the mould of unavoidable melodrama. The lecherous

Count attained by bitter qualms of conscience in the end; Leonora a

compassionate Madonna in light-blue train; Manrico a greyish bachelor,

moonstruck by misfortune and clearly a noble born-looser. Azucena towered

throughout in her fiery red gowns, as young and sexy as possible. Rather than

Manrico’s mother, she looked like his paramour, while a manly Ferrando kept

jerking her with ill-conceived desire. Side characters, nuns, warriors,

courtiers and sundry extras navigated smoothly, then suddenly disappeared

behind the boards. Perfect clockwork and grand opera on a grand scale, though

with limited means.