The Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona, after suffering a calamitous fire in the early 1990s, reopened in 1999, lovingly restored. TDK has released a series of DVDs from the Liceu since that date, providing ample evidence of the world class status of this house. All three of the stagings discussed here reflect the Liceu's high artistic standards and professionalism; unfortunately, none can lay claim to being a truly distinguished success.

The least impressive, coincidentally, first took the stage for the 1999 reopening of the house. As seen in a revival from 2005, the Turandot directed by Núria Espert comes across as a budget version of the Metropolitan Opera's Zeffirelli extravaganza. Heavy, elaborate costumes smother the singers, who rarely move well. Instead of Zefferelli's ornate sets, the front stage is mostly bare, with a more elaborate backdrop of stone carvings and heavier props carted on and off. Fog and lighting effects bring some atmosphere to the Emperor's entrance in act two. Espert also finds a clever way to end act one, which usually finds the Calaf holding the mallet with which he has struck the gong with an idiotic grin of triumph while waiting for the curtain to drop. Here, Turandot's guards wheel a cage onstage and cart the Unknown Prince away, a reminder of the murderous control the princess has over those who attempt to answer her riddles.

Although Espert uses the Alfano ending instead of the Berio completion (which premiered some years after this staging's creation), she foreshadows the ambiguity of the Berio version by having her Turandot stab herself at the end - a brutal contrast to the joyous chorus Alfano set the ending to. Gambits such as this can work if the entire production teases new meaning out of the work. However, this production has gone pretty much by the standard playbook from opening curtain, and so the twist at the end feels false and forced.

Although Espert uses the Alfano ending instead of the Berio completion (which premiered some years after this staging's creation), she foreshadows the ambiguity of the Berio version by having her Turandot stab herself at the end - a brutal contrast to the joyous chorus Alfano set the ending to. Gambits such as this can work if the entire production teases new meaning out of the work. However, this production has gone pretty much by the standard playbook from opening curtain, and so the twist at the end feels false and forced.

The singing doesn't redeem the director's muddled vision. Luana DeVol can carry the role's weighty demands well enough, but her wide vibrato and a cloudy middle voice make her a less than attractive princess. A bonus feature on her career, however, should make most viewers appreciate the dedication and effort that have led her to key assignments in many of the world's best opera houses. As Calaf, Franco Farina is his usual self: reliable in the sense of being able to manage some of the repertory's heavier tenor roles, but unimaginative and occasionally effortful. Barbara Frittoli suffers under a bad Jamaican beach-braid job, which may explain why she warbles a bit more than a Liu should really do. The Timur, Ping, Pang, and Pong are anonymously competent, and the same goes for Giuliano Carella's conducting.

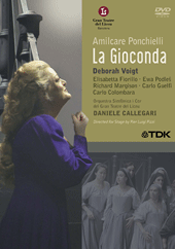

In staging the once vastly popular La Gioconda, a director can choose to go traditional and let the red-blooded effusions of the melodic Ponchielli score dominate the convoluted narrative, or seek to clarify the action with a more modern slant. For the Liceu in 2005, director Lier Luigi Pizzi took the latter approach. His handsome, spare set shifts around a a ramp of stairs that can suggest a bridge, before a vast blue background conveying both sea and sky. Splashes of red appear in the last acts, as the story line adds some gore. Costumes have been carefully chosen to fit into a color scheme of grays and steely blue, with the very low cut royal blue dress of our La Gioconda, Deborah Voigt, not being especially flattering. Richard Margison, the Enzo, forgoes his usual wig, and dressed in leather, has a certain masculine appeal - he might look right at home in a bar called, for example, "Rawhide." Voigt has all the voice for a role such as this, yet both the idiom and the character elude her. The sheer quality of her singing can't be denied, but it is a superficial pleasure. Margison has often been underrated. He lacks stage charisma, and the top never quite delivers all it promises, but the substantial body of the voice is handsome and tastefully delivered.

Both leads, and the bland Laura of Elisabetta Fiorillo, are upstaged by the great Ewa Podleś as La Cieca and the snarling malevolence of Carlo Guelfi as the villain Barnaba. Podleś has a stature on stage that is hard to convey - she seems to simply stand there, and yet embody her character. That self-confidence surely comes from her command of the deep, warm bounty of her voice. Guelfi's instrument itself is not as impressive, but he brings a welcome energy to his performance.

Both leads, and the bland Laura of Elisabetta Fiorillo, are upstaged by the great Ewa Podleś as La Cieca and the snarling malevolence of Carlo Guelfi as the villain Barnaba. Podleś has a stature on stage that is hard to convey - she seems to simply stand there, and yet embody her character. That self-confidence surely comes from her command of the deep, warm bounty of her voice. Guelfi's instrument itself is not as impressive, but he brings a welcome energy to his performance.

Conductor Daniele Callegari gives the score all the respect it deserves - probably more. The ballet is included, with a near-nude male dancer probably making most listeners put aside all memories of hippos in tutus. Ultimately, Pizzi's staging can't redeem the opera as drama, but as a "show," it works well enough.

The DVD of Graham Vick's staging of Verdi's Rigoletto comes from December 2004. The problem with many contemporary stagings of this masterpiece reappears here; directors can't help but explore the uglier sides of the story's view of human nature, so that the ample beauties of Verdi's score curdle, and Gilda ends up looking deluded to the point of ridiculousness, which limits the pathos. Marcelo Alvarez has rightfully earned a top ranking among today's tenors. He has total command of the Duke's music, and is a handsome enough singer, at least from the shoulders up. However, while no Pavarotti, Alvarez carries enough heft to make him less than agile on stage, and he can be a clumsy actor. It hardly seems credible that Inva Mula's Gilda would fall so deeply in love with this preening lout. Of course it is not Alvarez's fault that the director asks him to pick his nose and bite his nails. Mula's appealing Gilda works best with Carlos Álvarez as her father, Rigoletto. Compared to a classic vocal performance such as that of Robert Merrill, Álvarez cannot boast the same opulent tone. But apart from some rough spots that might be excused as dramatic license, his singing is as attractive as his make-up is ugly.

The depiction of Rigoletto as a truly grotesque figure, with a head almost as misshapen like the Elephant Man, is just one proof of Vick's tilting toward the misanthropic angle of the opera. Could there have been any other production where Gilda greets her father on his return home by lovingly washing his hump? Álvarez's make-up, by the way, seems to be quite hot, as sweat drips from his head often, further adding to the repellent portrayal.

Every act's set (designed by Paul Brown, who also did the costumes) features a revolving platform. For the Duke's court, the walls are gold. At first various women are posed around the circular wall, like a line of goodies for the Duke to choose from. For act two, they are pinned to the wall, victims of his lust. For Rigoletto's home, the set revolves to its most open side, and for some reason Vick has planted a large apple tree right in the center, for Gilda to climb up into for "Caro Nome." The set works well for the action of act three, which can be awkward to stage as Rigoletto and Gilda overhear so much action in Sparafucile's inn that the audience must also see. But why is Gilda dressed in a hideous purple and pink prom dress at the start of the act? At least her "boy" costume is more believable than usual. The heavy-handed director's touches continue right up through the last scene. Rigoletto punches and kicks the body in the sack that he believes is the Duke, and Gilda's legs kick. Then after the final duet, after propping up his daughter's body in an easy chair (why is that by the river?), Rigoletto shoves the chair over, dumping his beloved daughter's corpse to the ground.

And why the row of theater seats to the side of the revolving platform? Vick has had far too many ideas, and not enough point of view. But somehow, the strength's of Verdi's masterpiece survive. Viewers simply have to be prepared for an extremely unappealing vision of already dark material. Veteran Jesus Lopez-Cobos conducts with his usual detail and control.

Taken all together these three DVDs do not individually rank as first-rate performances, but each has some strengths, and they indicate that the Liceu is a house of strong musical standards. The productions are hit-and-miss, but that seems to be the way of the world, in 21st century opera.

Chris Mullins