Opera guide books tend to be a bit stuffy and boring, if indispensable.

One of the best, first issued in 1961, has just been updated and reissued in

a handsome softback from Amadeus Press.

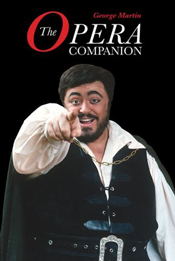

It is “The Opera Companion,” a 693-page, good-quality paperback by the

noted writer George Martin (a great bargain at $19.95). I cannot recommend

this engaging book too highly; in fact, if my library had to be restricted to

one book on opera, this would likely be it. Martin’s edition is of singular

design and organization. It consists of three major sections, The Casual

Operagoer’s Guide, a discursive consideration of many topics in opera –

pitch, the opera orchestra, history of the art form, the nature of melody –

and numerous others in a short, intelligent and pithy mode.

The second section is a dictionary-glossary of operatic and musical terms,

while the third section of Martin’s “Opera Companion” is a quite

detailed discussion of all aspects of forty-seven popular operas, from plot

to musical analysis. Martin’s accounts are so reasonable and well-informed,

I wish the number of operas treated were much larger. But he has chosen those

most often heard by today’s audiences, and in spite of my own sixty-years

of attending opera, I actually learned some new things about Gounod’s

Faust, for example, and Mozart’s Così fan tutte from

Martin.

In a time when that Mozart opera is foolishly treated by musicologists,

who find in Così deep and dark contradictions or profound psychological

themes, Martin’s clear-headed intelligent exposition of the music and text

is exactly what’s called for; he understands the opera and its style and

how it should be played. After reading Martin, you will too! His treatment of

Faust as a melodic operetta rather than deep grand opera is exactly right; I

recommend it and the entire book without reservation.

* * * * *

Put your hand up if you want to read a new tenor biography! Ummm....not

very many hands. I don’t blame you, they can be a self-aggrandizing bore;

most singer bios are. An exception was the Jussi Bjoerling book of a few

years ago, in which his truthful wife spoke out with refreshing candor.

Another exception is the new (2008) Amadeus Press biography of the greatest

Italian tenor of my lifetime, the golden Franco Corelli. In terms of vocal

power, color, quality and effectiveness, the Corelli tenor voice eclipsed all

others; in terms of a balanced lifestyle, the poor man suffered greatly from

all kinds of personal demons, stage fright and tenor-mania.

Holland-based René Seghers has written “Franco Corelli: Prince of

Tenors,” a beautifully printed and illustrated book, that thrives because

of excellent research, interviewing, and a strong narrative style. I picked

up this book about 4 p.m. one day, and in just a few pages I was hooked – I

read it all in one sitting, late into the night. I recommend starting

earlier!

Seghers treats all aspects of Corelli’s history, from birth in Ancona on

the Adriatic coast, to death in August 2003 in Milan, a demented and

emaciated 84-y.o. millionaire, whose wife would not keep him at home for she

feared his senile rages. The author, unlike many others, does not glamorize

his subject, nor does he soften the rough edges of Loretta Di Lelio,

Corelli’s possessive and controlling wife, who many believe made the

“adolescent” tenor’s huge career possible. Loretta herself freely

described her husband as immature and requiring constant care and attention.

This she supplied in abundance, though in later years he somehow escaped her

control and undertook some love affairs, which caused a temporary separation

of the Corellis. This contrasts with hilarious scenes of the Corellis’

backstage rituals before performances, when the terrified tenor, insecure and

superstitious, was sprinkled with holy water by Loretta, who would rub a

crucifix on his throat just before she pushed him onto the stage. The Corelli

anecdotes are legendary, as are his wars with opera managers, especially New

York’s Rudolf Bing, and Seghers gives them full treatment, even dispelling

some (Franco did not bite Birgit Nilsson in the Boston Turandot).

Of greater interest is Seghers’ thorough discussion of the evolution of

Corelli’s stunning vocal technique, which he worked on constantly

throughout his career. In the 1960s, in his forties, he often was in Spain

seeking to make his voice more fluid and lyric through studies with the great

Italian tenor of a generation before, Giacomo Lauri-Volpe, who helped him

significantly. Corelli’s finest vocal period was the mid and later-1960s,

and he readily credited the coaching of the senior Italian tenor di

forza.

Corelli’s major public career extended from about 1958 to 1975. The

author organizes the greater part of his book chronologically, touching upon

each season, where and what Corelli sang, and often with somea critical

analysis. This required prodigious research, and Seghers’ account has the

strong flavor of authenticity. In mid-career Corelli moved to New York City

and lived there until old-age; this facilitated his many seasons of dominance

at the Metropolitan Opera, where, along with Milan’s La Scala, the handsome

Corelli established himself as the most vocally potent and popular Italian

tenor of his era. “Prince of Tenors,” as a book, is a keeper; it is going

on my shelf and I expect to take it down often. Among other virtues, author

Seghers is an accomplished photographer and knows the value of visuals, so

has furnished his 526-page book richly with photographs, many never seen

before. The list price is a steep $34.95; Amazon is offering copies at

$21.95. Amadeus Press and René Seghers have done the vocal world a service

by publishing this invaluable biography of the wondrous Corelli.

* * * * *

Now, to the noted composer Dr. Paul Moravec. He is currently visiting

professor at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton, NJ, and is in

addition a professor of music at Adelphi University. Thus, Moravec is an

academic composer and distinguished musical scholar. His music, to my ear,

sounds exactly that – “academic,” if highly competent.

I bring this up because in Season 2009 you’ll be hearing a lot more

about Moravec, as his first-ever opera, “The Letter” (based on a 1927

play by Somerset Maugham, famous from the Bette Davis 1940 movie), is being

premiered at Santa Fe Opera, starring Patricia Racette in the Davis role of a

murderous wife.

I just listened several times to two Naxos recordings of Moravec’s

music, one, “Tempest Fantasy,” is a Pulitzer prize winner (Naxos 8.559323

), the other is “The Time Gallery” (Naxos 8.559267). Both are

interesting, and they share some traits. While the music lacks lyric line, it

is energetic -- busy and chattery (one friend called it “molecular”),

except when it makes a point to be quiet and mellow, which doesn’t last

very long, for its heart lies in smart antics and excitement, though these

particular selections are not much for originality or melodic effect.

I just listened several times to two Naxos recordings of Moravec’s

music, one, “Tempest Fantasy,” is a Pulitzer prize winner (Naxos 8.559323

), the other is “The Time Gallery” (Naxos 8.559267). Both are

interesting, and they share some traits. While the music lacks lyric line, it

is energetic -- busy and chattery (one friend called it “molecular”),

except when it makes a point to be quiet and mellow, which doesn’t last

very long, for its heart lies in smart antics and excitement, though these

particular selections are not much for originality or melodic effect.  There

is a lot more to this composer than these two CDs, and I wont comment more

because I have not heard his lyric writing. But considering that opera, even

“opera noir,” as Santa Fe is calling the forthcoming show, must be about

singing and lyric reach – if that does not occur, rather than true opera,

you have a play with music. While a novice opera composer, Moravec is an

accomplished and sophisticated man; and his text collaborator, the jazz

critic Terry Teachout, is a bright one too. So they may come up with a good

show; how “operatic” it will be remains to be seen. We hear it’s

90-minutes in length, with an orchestral interlude. Bette Davis is a hard act

to follow, but maybe clever Santa Fe can pull it off. The talented

singing-actress soprano Racette is clearly an asset; she was recently

reported advising the composition team on how to make their ending more

dramatic. Will this be opera by committee?

There

is a lot more to this composer than these two CDs, and I wont comment more

because I have not heard his lyric writing. But considering that opera, even

“opera noir,” as Santa Fe is calling the forthcoming show, must be about

singing and lyric reach – if that does not occur, rather than true opera,

you have a play with music. While a novice opera composer, Moravec is an

accomplished and sophisticated man; and his text collaborator, the jazz

critic Terry Teachout, is a bright one too. So they may come up with a good

show; how “operatic” it will be remains to be seen. We hear it’s

90-minutes in length, with an orchestral interlude. Bette Davis is a hard act

to follow, but maybe clever Santa Fe can pull it off. The talented

singing-actress soprano Racette is clearly an asset; she was recently

reported advising the composition team on how to make their ending more

dramatic. Will this be opera by committee?

J. A. Van Sant © 2008