For shortly into their thoroughly entertaining mounting of this 17th Century rarity, our leading bass-baritone morphed from a Louis Quatorze persona into a quasi-cartoonish hero by strapping on muscled legs, arms and torso (think: comic Ninja Warrior padded outfits), stringy blond wig, and knee high black platform boots. Oh, yeah, and brandished a Flintstone style club.

Luca Pisaroni gave a consistently animated impersonation as Ercole (Hercules), narcissistically mugging, and grimacing orgasmically enough that he may have a future in porn should his skyrocketing international opera career stall. He clearly relished the goof on contemporary hero worship, and all the while sang most mellifluously and, when required, forcefully. Mr. Pisaroni may not have the booming low notes of some, but his is a fine, well-projected voice with a sound technique, and (sans padding) he has a lean, handsome stage presence.

His achievement was equaled by the elegant Giunone (Juno) of Anna Bonitatibusnoa, an audience favorite who appeared as a sleek, gliding “Woman in Black.” She deployed her rich-hued, earthy instrument to marvelous effect, forging an uncommonly affecting presentation of the opera’s go-to girl.

Jeremy Ovenden’s Illo (Illus), Herc’s son, is got up as a cross between Blue Boy and Buster Brown, and the lyric tenor indeed delivered on the visuals with a boyish, cleanly sung performance. Having admired his Orfeo last season, I still have the feeling that in spite of his eminently pleasing tone, stylistic command, and total commitment, he is not naturally a creature of the stage.

Not so the engaging Tim Mead, a real discovery to me, who did double duty as Paggio (Page) and Ombra di (Ghost of…) Bussiride. His personalized and characterful counter-tenor had the zing of a sassy mezzo, and his high energy portrayal (in a shiny metallic gold and black striped fitted tunic-‘n’-tights) stole many a scene. Topped off with anachronistic horn-rimmed glasses, the delectable Mr. Mead may have been slight of frame, but he dominated the stage whenever he appeared.

Anna Maria Panzarella made a fine impression as Deianira, aka Mrs. Hercules, sumptuously outfitted as she was in colorful period queenly attire. Ms. Panzarella gifted us with a richly detailed and sparkling vocal presence. Marlin Miller’s Licco (Lichas) featured a well-focused tenor in an energetic traversal of a less than interesting role. Veronica Cangemi made a nice contribution as Iole, who also motivates the plot even if she lacks splashy writing, especially scoring with a limpidly voiced prolonged duet with Illo.

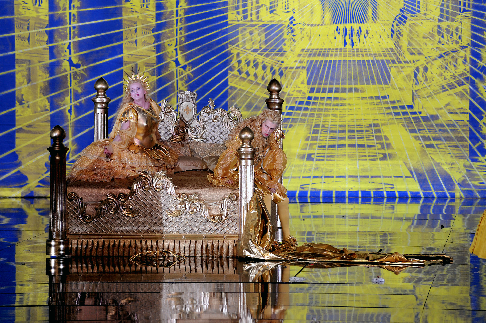

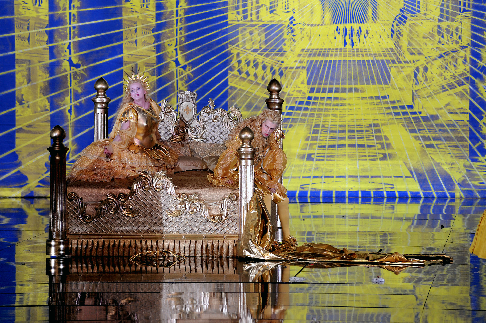

Umberto Chiummo (Nettuno), Jeremy Ovenden (Illo)

Umberto Chiummo (Nettuno), Jeremy Ovenden (Illo)

Umberto Chiummo gave pleasure plying his bass in service of three roles: Nettuno (Neptune), Tevere (The Tiber, as in River), and Ombra di (Ghost of) Eutiro (Iole’s father).

While I have often enjoyed the lovely soprano Wilke te Brummelstroete, she was a bit off form on this date, her slightly diffuse tone (only) occasionally straying a bit from pitch in a dual assignment as La Bellezza (Beauty) and Venere (Venus). Johannette Zomer (Cynthia, Pasitea, Ghost of Queen Clerica) and Mark Tucker (Mercury, Ghost of King Laomedonte) made solid contributions in their small roles.

Musically, the redoubtable Ivor Bolton led another well-prepared, beautifully-paced, yet abundantly spontaneous reading, making the period band respond with well-judged results. I was struck by the variety of Cavalli’s writing, and the remarkably fresh percussive effects. The score may have two or three finale ultimo’s (ultimi?) too many, but this was for me a revelatory musical performance from first rate singers and the masterful Concerto Köln.

Johannette Zomer (Pasitea)

Johannette Zomer (Pasitea)

Director David Alden had enough clever ideas for four average productions, and his inspired lunacy (and sensitivity, too) found willing accomplices in scenic designer Paul Steinberg, lighting guru Adam Silverman, and costumer Constance Hoffman (her witty, whimsical, whacked out designs had to have been born in an Amsterdam “coffee” house!) This was a show where most every bit of wholesale “invention” landed.

The opening Chorus of Rivers was visually arresting, the large chorus (excellently schooled by Tim Brown and Martin Wright) in vibrant deep purple satin costumes, cavorting and “swimming” in the “sea” of shaken cloths, surrounding an “island” of a Cardinal (Tiber) in brilliant red.

The underworld scene at Eutiro’s monument is here brilliantly imagined as a riff on the Thriller video with skewed caskets popping open and mummified dancers as graveyard revelers, confronted eventually by the cockeyed red steps of Hades rising from the depths. The earlier similar trap door appearance of Neptune surrounded by fanciful statues of romping silver sea horses was yet more visual eye candy.

The three graces appear revealed as singing heads who pop through advent calendar-like doors in a huge reproduction of …the three graces. The gloriously ethereal music in the “sleep” trio, was visually enhanced by a stage composition built around a snoozing codger in a Once Upon a Mattress style bed. There was even a nod to Flash Gordon, making an appearance as an ersatz Atlas struggling mightily to carry the weighty globe, of which Herc Hogan divests him, carrying it easily and cockily. I am not sure what the huge dancing Betsy-Wetsy baby doll was doing there in the mix but it sure was fun!

Worthy of very special note: Jonathon Lunn’s Puckish choreographic style was sort of, well, Pina-Bausch-meets-Mark-Morris-as-imagined-by-Matthew-Bourne. Quirky, anachronistic and clever as hell. I loved every warped chassé and approximated be-bop hand jive twitch.

I know, gentle reader, that this sounds like it could easily be one of those let’s-throw-a-bunch-of-stuff-together-and-to-hell-with-the piece sort of eclectic grab bag approach that often passes for opera “direction.” It was often busy, yes, but the character relationships, the through-line of the plot, and the essence of the piece were extraordinarily clear.

Wilke te Brummelstroete (Venere), Luca Pisaroni (Ercole)

Wilke te Brummelstroete (Venere), Luca Pisaroni (Ercole)

Still, there is a difference between inventive staging and over-staging and the opening of the second half, while entertaining, up-staged poor Illo pretty badly. I quite loved the jumbo tracked fish, swimming from one wing to the other; and the Page in a sailboat, like the Pussycat caught without the Owl, was a hoot as he was hilariously tossed about in a daffy storm effect.

But through all of this, poor Mr. Ovenden was perched upstage framed by a large hole (suggesting his looking into the lake), and well, although he was pouring his heart and soul into what seemed to be a difficult florid aria, he could have had a sparkler in his teeth and no one would have been paying any attention to him. Still, when he later “jumped” into the lake from on high, it was a wonderful effect to leave him hanging in the air by a wire, as if floating in the water’s current.

That major quibble aside, by opera’s end, when a dazzling electric neon yellow and blue backdrop displayed the rays of a sunburst; and the chorus promenaded in glowing golden yellow satin costumes; and the ebullient dance corps hurdled, bounced on, hopped over, and somersaulted into an over sized bed, I myself felt a celebratory cartwheel inside me just waiting to get out. (Only self-control and journalistic decorum held me in check in the lobby).

Once again, the adventurous Dutch National Opera and its artists made some bold and risky choices. With Ercole Armante, they paid off with dazzling results.

James Sohre