30 Aug 2009

Fidelio at the Proms

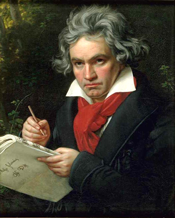

Fidelio is not just any opera. But then, Beethoven is not just any composer. His only opera — unless one counts Leonore as a work in itself — confounds bureaucratic expectations.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

Fidelio is not just any opera. But then, Beethoven is not just any composer. His only opera — unless one counts Leonore as a work in itself — confounds bureaucratic expectations.

The unimaginative and the plain uncomprehending are led to decry it and sometimes, quite staggeringly, to account it a dramatic failure. Even Wagner, who should have known better, could be dismissive, for instance telling Cosima that a German theatre would be better off opening with Weber’s Euryanthe — admittedly, a wonderful work, but certainly a problematical one — “rather than with Fidelio, which is much more conventional and cold.” Conventional? Hardly, given the boldness of substituting for the operatic expectations of conventional “characterisation” the instantiation of an unutterably noble idea, “freedom”, itself liberated from the confines of bourgeois expectations. Wagner either could not see, or did not want to see — the latter, I suspect, more likely — that the “rescue opera” was here both transcended and granted its enduring memorial. Cold? This work veritably blazes with heat, and it certainly did on this occasion, “occasion” being truly the operative word. Still worse, we read Cosima a few years later record, again contrasting the work with Richard’s beloved Euryanthe: “Then we start discussing Fidelio, which R. describes as unworthy of the composer of the symphonies, in spite of splendid individual passages.” Suffice it to say, however, that there were here many “splendid individual passages,” yet Fidelio was found not only to be worthy of the composer, but to speak directly of and to that all-too-real modern-day catastrophe to which the very existence of the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra bears witness.

So much for what one might call the meta-performance, but what of the performance itself? Daniel Barenboim has rightly chided those who speak only of the context to this orchestra and not of its musical accomplishments. One cannot and should not forget the former, but the greatness of the enterprise shows in the extraordinary artistic results; disentangling the two is a fool’s game, and never more so than in a work such as this. I am delighted therefore to report that the expectations built up from the previous night’s two Proms (see here and here) were more than fulfilled. Indeed, the orchestral playing had a greater edge than it had during the first half of the first of those concerts. The strings once again demonstrated a depth that would be the envy of many a professional orchestra — at least it would, were the absurd authenticist fashion not to decry such tone. Occasionally the woodwind might have proved fallible, but so what? One does not expect Klemperer’s Philharmonia, astonishing in a different way. This work is about humanity, warts and all: just, in fact, what Beethoven is about. There were in any case ample compensations in the Harmoniemusik blend. The timpanist, a star from the previous night, once again shone brightly. The brass was often magnificent, nowhere more so than in those treacherous horn parts in Leonore’s first-act aria. They were not outshone by Waltraud Meier, which is saying something. And then, of course, there was that trumpet call. The thoughts and associations that rushed through one’s mind at that point were myriad, but I can certainly report that it brought tears to my eyes.

Barenboim’s direction was vigorous, unfailingly engaged, attentive to singers and orchestra, without ever letting concerns for the possible detract from the necessity of the utopian. Some of the overture — unwisely, I thought, Leonore III — was impetuous rather than climactic in a Furtwänglerian sense. (The performance these musicians gave of the overture “as itself” in Salzburg two years ago was manifestly superior.) But his remained a signal achievement, not least in terms of orchestral training, discipline, and of course inspiration. The other cavil I should register is with the version of the score employed. Messing about with Fidelio seems to be all the rage at the moment. The Paris Opéra recently commissioned new dialogue and re-ordered the opening sequence, beginning moreover with Leonore I. Barenboim did something similar, in eschewing almost all of the dialogue — is it really that bad? — and putting Marzelline’s aria before her duet with Jaquino (without, moreover, the tonal justification for this put forward by Sylvain Cambreling in Paris). But then, I realise that I was speaking above about confounding of expectations, so perhaps I am just lacking in imagination myself. There was, in any case, a reason for replacement of the dialogue, since it was replaced by Edward Said’s English narration for Leonore. On this of all occasions, to do so was quite understandable and it certainly provides a genuinely interesting and in some respects disquieting perspective upon the work. Hearing Leonore recount what had taken place from a chronological distance, and with clear implications that her hopes had since been dashed or at least significantly tempered, warns us against any move towards easy non-solutions. Don Fernando could never have put everything right.

Waltraud Meier, mostly recorded but also partly live, presented the narration vividly, in delightfully accented English. However, it was her vocal-dramatic performance that stole the show. She is of course a true stage animal; this shone through in her facial expressions, her gestures, as well as her voice. Yet, even though this was a concert performance, her performance was certainly not out of place. She actually brought us into the most important theatre of all, that of the imagination. And her account of “Abscheulicher! ... Komm, Hoffnung” was simply spellbinding. Simon O”Neill was an excellent Florestan. He could not efface memories of Jonas Kaufmann in that Paris performance last December, but to have hoped for that would have been entirely unreasonable. O”Neill proved himself fully capable of the testing demands of this cruel role and even brought the odd hint, if only a hint, of Jon Vickers to his timbre and projection. Gerd Grochowski was a late replacement for Peter Mattei as Pizarro. I have recently heard him both in Berlin and London as Telramund, and this performance was rather similar, evincing commendable attention to musical and verbal text, but remaining underpowered. This was undoubtedly exacerbated by the presence of Sir John Tomlinson as Wotan, sorry, Rocco. Tomlinson’s voice might be showing its age on occasion, but this is as nothing compared to the dramatic truth and commitment he shows. It was, however, somewhat unfortunate that Rocco should from the outset be so much more powerful a presence than Pizarro. Evil might or might not be banal, but we need to believe in the very real power this wicked man wields. The other parts were decently taken, Adriana Kučerová showing to good effect a beautiful voice, of which I should be more than happy to hear more. And it would be unforgivable not to mention the truly outstanding singing from the combined forces of the BBC Singers and the Geoffrey Mitchell Choir. Every note, every word, was audible, but just as immediate was the dramatic effect, whether of imprisonment, of hope, or of jubilation. The legendary Wilhelm Pitz’s Philharmonia Chorus for Klemperer is the gold standard here, but these musicians, if not so great in number — or at least that is how it sounds — have little to fear from such a comparison.

Wagner was doubtless right to prefer the Ninth Symphony for the laying of the foundation stone at Bayreuth. Yet the Ring, the sometime artwork of the future, is not the only nineteenth-century work that speaks immediately to our present condition. Fidelio does too (which is not, of course, to say that many other works do not). And so, still more so, does a performance of Fidelio such as this. Barenboim seems to me both right and wrong to say that when this orchestra comes together, politics disappear, since everyone must concentrate exclusively upon the music. For that coming together in the service of something far greater is unavoidably political. It shames those who create division and worse; it holds up an alternative. Such, after all, was the original intention of Barenboim and Said. To the orchestra, mere congratulations upon a tenth anniversary few, least of all its founders, could ever have anticipated, seem pitifully inadequate. And to Blair, Bush, Olmert, Ahmedinejad, Mugabe, Putin, et al., one wants, indeed needs, to say once again, with Horace, “Mutato nomine, de te fabula narratur” (“Change but the name, and the tale is told of you”). Even if we cannot quite bring ourselves to believe that present-day tyrants and war criminals will be brought to justice, we must hope — and hope that at least some of their victims will be rescued. Beethoven and these inspirational young musicians help us do that. “Komm, Hoffnung...”

Mark Berry