16 Oct 2009

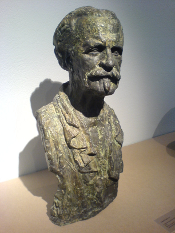

Fervaal by Vincent d’Indy

Vincent d’Indy lived eighty years and, when not composing, spent his time revising the teaching of music in France or simply annoying everybody.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

Vincent d’Indy lived eighty years and, when not composing, spent his time revising the teaching of music in France or simply annoying everybody.

Nineteen when Prussia tramped all over his beloved France in 1870, he became a passionate nationalist with all the excesses of the time and place: anti-Germanism became, for him as for many, a racial “Celticism,” and his Francophilia included royalism, anti-Dreyfusism and anti-Semitism. Yet he was too good a musician not to appreciate Wagner and be influenced by Wagnerian method.

As a composer of opera, d’Indy was part of that post-Wagnerian movement determined to find in local folklore ways to celebrate national glory, a movement that produced dozens of works from Ireland to Armenia, most of them long forgotten — Humperdinck’s Hansel und Gretel is a rare success and survival. D’Indy’s Fervaal, which affects to find in the druids a mythic antidote to sophisticated modern life, is d’Indy’s contribution. It had its premiere in Brussels in 1897 and reached Paris in 1913 — just in time for this sort of perfervid nationalism to cheer entry into World War I; Fervaal has not been fully staged anywhere since. That the hero, a druidic prince of divine descent vowed to chastity — though how that will preserve his dynasty is not made clear — is seduced by the love of a “Saracen” princess. Their doomed union prefigures the death of the old gods and the birth of a world based on love (sound familiar?). The Celtic-Saracen passion might appeal to multiculturalists in modern France, with its huge, disaffected Muslim population, but would probably not delight the aristocratic d’Indy and leaves the auditor puzzled.

Still, as a concert version presented by the American Symphony Orchestra under that indefatigable lover of obscure scores, Leon Botstein, made clear, Fervaal is extraordinary without being especially endearing. The great flaw is that none of the three principal characters has much personality — they declaim at taxing length but they never persuade us that they feel any of the emotions they announce. They do not persuade us that they exist — that they have inner lives, emotions that can be reached by other persons. None of their music possesses the charm d’Indy gives to his choruses, who are variously and convincingly warring tribes, exultant priests, sensuous Saracens, spirits of the clouds or natural forces moaning as storms or winds. D’Indy might have achieved success with a dramatic oratorio had he ever composed one — grand opera on the Meyerbeer or Wagner pattern does not bring out his best.

The opera’s enormous orchestra lacked (Botstein said) several instruments d’Indy requested that are no longer much played. There were an enormous variety of winds and brasses typical of the period, exquisitely deployed: contrabass clarinets, for example, and four saxophones to accompany the apparition of the cloud-goddess Kaito and her cumulonimbus attendants — an answer for those who have doubted the spiritual qualities of the saxophone sound. For orchestral color, d’Indy was clearly a master of the genre — he is perhaps best known for his set of orchestral variations on the legend of the Descent of Ishtar — played in reverse from most complex to least, as the goddess disrobes to her naked theme.

My heart went out to the three lead singers — especially to Richard Crawley, a last-minute replacement, who had to learn the title role (easily as long as either Siegfried) in two and a half weeks — for the acres of ungrateful declamatory singing they were obliged to hurl out at Fisher Hall all evening. That they could pace themselves and did not run out of steam is a tremendous tribute to the professionalism of all hands. Donnie Ray Albert may lack the Wagnerian surge and sonorous depths that d’Indy appears to have hoped for in Arfagard, the uncompromising druid priest and prophet, but his sturdy bass-baritone never lost authority. Deanne Meek’s clear mezzo-soprano probably has some sensuous notes somewhere, but she didn’t much display them as the Saracen princess Guilhen, though one would have thought “seductiveness” part of the job description. She, too, deserves points for unflagging industry. Barbara Dever sang the small but distinctive role of Kaito, whom d’Indy calls the goddess of the clouds — but he wrote it and she sang it in the style and intensity of Wagner’s Erda, a part she could obviously handle whenever called upon. Many small roles were ably covered and the Concert Chorale of New York were especially virtuosic, with the only really lyric singing of the occasion.

John Yohalem