![Claire Booth (lying) and Susan Bickley (standing) [Photo by Alaistair Muir courtesy of The Royal Opera]](http://www.operatoday.com/ITLH064.png)

26 Jul 2010

George Benjamin: Into the Little Hill, Linbury, London

George Benjamin is the leading British composer of his generation. Into the Little Hill premiered in 2006, has been acclaimed a masterpiece.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

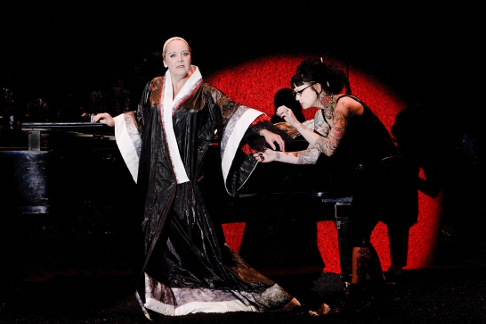

![Claire Booth (lying) and Susan Bickley (standing) [Photo by Alaistair Muir courtesy of The Royal Opera]](http://www.operatoday.com/ITLH064.png)

George Benjamin is the leading British composer of his generation. Into the Little Hill premiered in 2006, has been acclaimed a masterpiece.

This revival, at the Linbury Studio Theatre at the Royal Opera House, London, confirmed its place as a cornerstone of modern British repertoire.

It’s very loosely based on the fairy tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, where a conformist community rat on the piper who rids them of vermin. So he takes their children into a “little hill”. The one act opera is disturbing because it treats the story as nightmare.

Into the Little Hill operates on many different levels at once. There’s a political element.The mob violently demand the extermination of all rats, and the Minister sells his principles for votes. There’s a suggestion that the rats aren’t rats but other humans. As the Child says, they wear clothes and carry suitcases — an echo of the Holocaust? There’s social commentary, and the spectre of child abduction, all the more disturbing as the father is implicated.

Nightmares are powerful because they reveal themselves through portents, subliminally working on the subconscious. This is a work that defies classification. Quite likely Benjamin and his librettist Martin Crimp can’t explain its full portent, because it operates on the unconscious, on a subliminal level which cold logic cannot reach. That’s why it’s endlessly intriguing. Perhaps the way to get into Into the Little Hill is to let your intuition lead you.

The Minister’s Child appears to her mother in a chink of light.”Come home” says the mother. No, says the child, “Our home is under the earth. With the angel under the earth” What can that mean, no-one knows. But as the child says “The deeper we burrow, the brighter his music burns”. “Can’t you see?” cries the child. The child sees, because it doesn’t carry the millstone of received wisdom.

Into the Little Hill operates like a half-remembered dream, flotsam flowing out of the unconscious, to be processed in the listeners mind. Rats invade the town, eating grain and concrete, destroying the foundations of social order, Later, the children disappear into the bowels of the earth. “We’re burrowing” sings the child, “streams of hot metal, ribbons of magnesium, particles of light”.

A “man with no eyes, no nose, no ears” materializes in the Minister’s little daughter’s bedroom. He invades the sanctuary, mysteriously, disturbingly.. He is powerful because he can breach all defences, even the Minister’s office. “With music I can reach right in /march slaves to the factory/ or patiently unravel the clouds” Sinister as he is, he’s morally neutral — “The choice is yours” he says to the Minister.

The whole opera pivots on ideas of dissimulation, concealment, crawling into dark recesses. Nothing is safe. So the music here is cloaked in disguise. You hear something eerie, or harps or bells. Sure enough, there’s a cimbalom right in the heart of the orchestra. You hear something tense, tinny and shrill: it’s a banjo, and conventional strings being played like banjos, strings plucked high up the shaft, not bowed. Much emphasis on low-toned instruments like bass flute and bass clarinet, whose sensuous, seductive themes weave through the piece like a narcotic night-blooming flower.

Susan Bickley and Claire Booth sing. The parts aren’t defined, as such. Their voices interchange, with each other and with the “voices” in the orchestra, adding to the unsettling, dream-like effect. Bickley and Booth are the foremost interpreters of modern music in this country. They are superb. Good as the recording on Nimbus is, the singers there don’t come close to Bickley and Booth, who have lived this piece for some time. If Bickley, Booth and the London Sinfonietta record this, their version will be the one to get.

Their expertise matters, because this singing has to be approached with an almost intuitive understanding of how the vocal parts interact with the music. Both are attuned to the inner logic of the piece, so the ever-changing balance flows seamlessly. Although the text is conversational, the syntax is surreal. At several points, Booth has to “sing” at such a high pitch she’s almost inaudible. It takes physical effort. She braces herself, so as not to strain her voice beyond the limits. Humans might not hear such pitches, but rats can.

The staging, by The Opera Group, (director, John Fulljames), fits the music and the semi-narrative. The Man with no Face operates through music : the London Sinfonietta play on stage, behind a gauze curtain, vaguely visible behind the action, very much part of the concept as the orchestra is so important in this opera. The stage is dominated by a huge circular frame. “I can make rats drop from the rim of the world” says the man with no eyes. “But the world, says the minister, is round”. “The world — says the man — is the shape my music makes it.”

Susan Bickley [Photo by Robert Workman]

Susan Bickley [Photo by Robert Workman]

The floor is scattered with black, soft objects. When I attended the performance at Aldeburgh in June, I was close enough to touch and smell the acrid stench of rubber. It’s a striking extra dimension. By the time the production reached London the smell was almost gone. It was less oppressive, but gone too was the extra element of menace. Like music, smell can’t be seen but it operates on the mind.

Into the Little Hill was preceded by Luciano Berio’s Recital 1, It’s a tour de force, testing a singer’s full range. It’s a stream of consciousness monologue. Susan Bickley was magnificent, singing for nearly 45 minutes. Snatches of Lieder and Opera rise to the surface, receding as her mind moves on to other things. It’s tragic, for the singer is desolate, looking back on a lifetime of loneliness.

Since Berio wrote it for Cathy Berberian long after their marriage ended, it’s bittersweet, but also strangely affectionate. The interplay between singer and orchestra reflects the interplay between composer and muse. Many in-jokes, such as when Bickley sings “A composer is socially embarrassing when he tries to speak”. But that’s the whole point, for Berio speaks through the orchestration, The piece is an elaborate puzzle-game, tightly scored with intricate key changes and modulations.

Berio plays with illusion. At one stage, members of the orchestra emerge to share space with Bickley. They start to play, but the sounds are grotesquely distorted. Then they exchange instruments. What do these musicians normally play? This was the London Sinfonietta, Britain’s best contemporary music orchestra, an ensemble of virtuosi. Berio is having a laugh, for the rest of the piece is so sophisticated that bad players would be completely lost.

Bickley leans towards the audience, trying to get them to respond to her directly. I very nearly did. Berio and Berberian would have been thrilled, for part of the concept behind this piece is the relationship between illusion and reality. “Isn’t all life there?”, declaims Bickley, with a diva-like sweep of her arms.

For more information please see the Royal Opera House site here.

Anne Ozorio

Cast:

George Benjamin: Into the Little Hill (Martin Crimp: libretto)

Susan Bickley, mezzo-soprano; Claire Booth, soprano. London Sinfonietta. Frank Ollu: conductor.

Luciano Berio: Recital 1

Susan Bickley: The Singer; John Constable: The Accompanist; Nina Kate: The Dresser. The Opera Group. John Fulljames: Director. Soutra Gilmour: Set and Costume Designer. Jon Clark: Lighting.

Linbury Studio Theatre, Royal Opera House, London. 23rd July 2010