18 Jul 2010

Mahler’s 8th at Royal Albert Hall

A performance of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony could only ever be relatively underwhelming; even a car crash of a performance would impress in some sense, indeed most likely in quite a few.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

A performance of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony could only ever be relatively underwhelming; even a car crash of a performance would impress in some sense, indeed most likely in quite a few.

Yet this First Night of the Proms underwhelmed to an extent that surprised, a state of affairs for which responsibility lay squarely at the door of the conductor, Jiři Bělohlávek. Whatever the strengths of the present Principal Conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra may be, they always seemed unlikely to lie in Mahler, and so it proved. Should a performance of this work turn out to be merely a pleasant enough experience, something has clearly gone awry. It was not even wrong-headed enough to interest in the sense that, say, Sir Georg Solti’s relentlessly hard-driven, unabashedly operatic recording might, although, almost paradoxically, in its soft-grained way, it perhaps stood closer to such a reading than to probing renditions by the likes of Jascha Horenstein, Dmitri Mitropoulos, Pierre Boulez, or Michael Gielen.

My first impression was favourable, Bělohlávek rendering Mahler’s counterpoint surprisingly clear, apparently placing the work in the tradition of the composer’s fifth symphony. Doubts soon set in, however. The first ‘slower’ section set the pace, or lack of it, for its successors. Mahler writes, following his a tempo indication, ‘Etwas (aber unmerklich) gemäßigter; immer sehr fließend.’ Instead of relative moderation and care always to flow, the music almost ground to a halt. This is not simply a matter of tempo, of course; vitality was lacking. Returning to the comparison with Solti, the solo quintet sounded too ‘operatic’, in an almost Italianate sense: Mahler for those who prefer Verdi, albeit without fire. Bělohlávek guided a clear enough course through the first movement, but the reading was very four-square, lacking in dynamism, and ultimately quite debilitating in terms of its sectional approach. The work’s structure needs to be brought out, but just as important to that is the unity of the movement and indeed of the symphony as a whole. And so, the ‘Accende…’ music, exciting in itself, did not seem to come from anywhere. Moreover, the orchestra was underpowered — indeed, surprisingly small: just sixteen first violins down to eight double basses. The strings, especially during the first part, often sounded scrawny and there were uncomfortably shrill moments from the woodwind. There was, however, some splendid duo work towards the end of the movement from the kettledrums, and the presence of the Royal Albert Hall organ (Malcolm Hicks) was throughout impressive, almost violently so at times. Choral singing was here and elsewhere very fine indeed, undoubtedly the saving grace of the performance. Applause marred the conclusion of this first part.

The opening of the second part flowed but lacked mystery — at least until the sounding of beautifully grave horns, followed by shimmering violins: a passage to savour. The brass section was resplendent, yet it was impossible to overlook the general lack of depth to string tone. Mahler’s music needs to resound as if hailing from the bowels of the earth, not as if it were a thin layer of turf lain on the surface. Matters improved, however, once the chorus re-entered, and the echo effect was unusually impressive: not easy, with these forces. Hanno Müller-Brachmann was a typically thoughtful, beautiful-toned Pater Ecstaticus, and Tomasz Konieczny more or less followed suit, if hardly de profundis, as Pater Profundus. Stephanie Blythe stood out amongst the female soloists: a mezzo, but with hints of an earth-mother contralto. Stefan Vinke was a very late substitute for the indisposed Nikolai Schukoff as Doctor Marianus. He sounded a little nervous to start with, but grew into the part, though without the virility that so impressed me when I saw him in Leipzig as Lohengrin and Parsifal. (Doubtless the size of the hall has something to do with it too, but if ever there were a Royal Albert Hall work, it must be this.) Twyla Robinson improved dramatically as Una Poenitentium, the words of her first stanza indistinct, diction much superior thereafter, and with a glorious tone in conclusion: ‘Vergönne mir, ihn zu belehren, noch blendet ihn der neue Tag!’ Choral singing was once again of a very high standard; I was especially taken by the lovely tone of the Chorus of Blessed Boys as they circled (at least in one’s imagination).

The conductor, however, continued to let the side down. Thematic links with the first part were clearly brought out, but that was one of the interpretation’s few virtues. (In any case, the connections are pretty difficult to miss!) Orchestral heft was simply lacking; for much of the time, Bělohlávek sounded as though he would have been more at home with Mendelssohn or, at a push, Schumann. The latter’s Scenes from Goethe’s Faust might have responded better to such treatment, though I fear that that work would have lacked fire too. Slow passages dragged and accelerations sounded arbitrary. There were some beautiful instrumental moments, for instance the sound of strings, harps, and harmonium as Mater Gloriosa floated into view, but again this was too much of a slow section in itself, preceded by an inordinately distended and downright sentimentalised ‘Jungfrau, rein im schönsten Sinne…’ from Doctor Marianus and chorus. It was again the latter that shone in the final Chorus Mysticus: beautifully sung, but that is not nearly enough. A performance of this work that fails to grab one by the scruff of one’s neck is barely a performance at all.

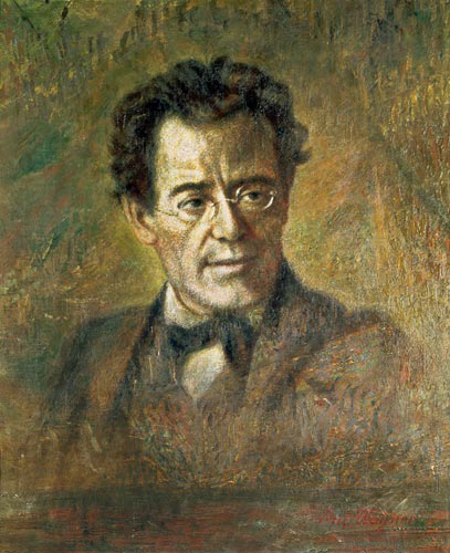

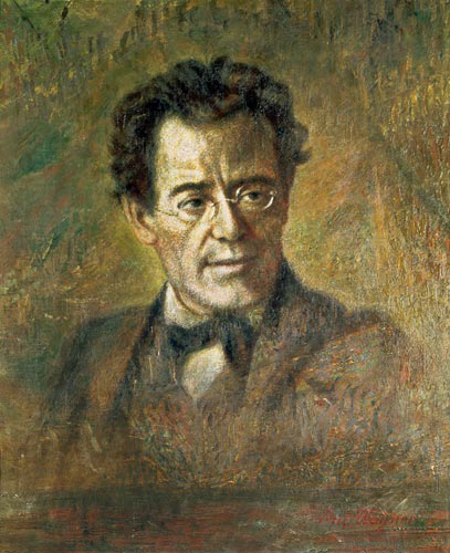

Mark Berry