Recently in Performances

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

The doors at The Metropolitan Opera will not open to live audiences until 2021 at the earliest, and the likelihood of normal operatic life resuming in cities around the world looks but a distant dream at present. But, while we may not be invited from our homes into the opera house for some time yet, with its free daily screenings of past productions and its pay-per-view Met Stars Live in Concert series, the Met continues to bring opera into our homes.

Music-making at this year’s Grange Festival Opera may have fallen silent in June and July, but the country house and extensive grounds of The Grange provided an ideal setting for a weekend of twelve specially conceived ‘promenade’ performances encompassing music and dance.

There’s a “slide of harmony” and “all the bones leave your body at that moment and you collapse to the floor, it’s so extraordinary.”

“Music for a while, shall all your cares beguile.”

The hum of bees rising from myriad scented blooms; gentle strains of birdsong; the cheerful chatter of picnickers beside a still lake; decorous thwacks of leather on willow; song and music floating through the warm evening air.

Performances

![Sonia Ganassi as Rodelinda [Photo by Laera]](http://www.operatoday.com/7133.png)

10 Aug 2010

Middle Ages Next to Come

According to Paulus Diaconus’ Historia Langobardorum, both

Lombard sovereigns warring for supremacy in late 7th-century Italy — the

legitimate king Perctarit and Grimuald the usurper — behaved rather fairly to

each other and their families.

Above all, there is no evidence that they would

compete for queen Rodelinda, who instead was exiled to Benevento with her

little son Cunincpert and lived peacefully there until Perctarit, after finally

recovering the throne, summoned her back to the kingdom’s capital

Pavia.

Turning into melodrama characters those practical barbarians, more

interested in power than in romance or bloody vengeance, was the endeavor of

such Baroque playwrights as the French Pierre Corneille and the Florentine

Antonio Salvi. The latter’s 1710 libretto for Giacomo Antonio Perti

(Rodelinda, regina de’ Longobardi), drastically pruned by Nicola

Haym for the London stage, was set to music by Handel in 1725. It immediately

proved a resounding success, also thanks to a cast including soprano Francesca

Cuzzoni in the title role, the legendary Senesino as Bertarido, and some of the

best singers available in the side-roles: tenor Francesco Borosini, bass

Giuseppe Maria Boschi, and alto castrato Andrea Pacini.

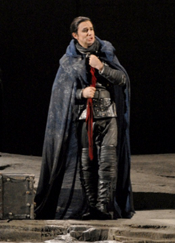

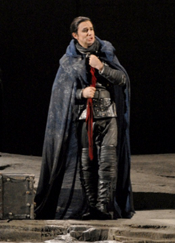

Franco Fagioli as Bertarido [Photo by Laera]

Franco Fagioli as Bertarido [Photo by Laera]

The present staging in Martina Franca, a festival traditionally claiming to

“authentic” performing practice, plunged the romanticized

18th-century music drama back into the darkest Middle Ages, or into a

“Middle Ages next-to-come”, as phrased by director Rosetta Cucchi.

At least visually, through the combination of muddy and disheveled landscapes

with costumes (by Claudia Pernigotti) featuring leather, rags, metal

decorations, and heavy-duty boots. Entertaining enough, but how much

“authentic” is questionable, if only one checks Senesino’s

portrait as Bertarido in the flamboyant livery of a Hungarian haiduk,

as painted by John Vanderbank in 1725. At the most, this is

Regietheater that dare not speak its name, a compromise likely to

dissatisfy modernists and authenticists alike.

The show’s musical side was far more convincing, with the Swiss

conductor Diego Fasolis succeeding to elicit from the festival orchestra

— equipped with modern instruments plus harpsichord, theorbo and Baroque

flute — a sound that was both luscious and historically informed. Within

an evenly balanced company, the Argentinean alto Franco Fagioli (Bertarido)

towered for projection, agility, seamless transition between registers,

unfailing musicianship. His manly color and stage charisma may set a new

standard among countertenors. As Rodelinda, mezzo Sonia Ganassi tended to

underact throughout and suffered some strain in the upper register. For her

convenience, a couple of high pitches were transposed an octave lower, and her

whole climactic aria “Ombre, piante” was set in G minor instead of

the original B minor. Nevertheless, she sang with an elegant restraint hitherto

unnoticed in her main repertoire, stretching from Rossini and Donizetti to

Massenet.

Her sister-in-fiction Eduige (the established Baroque specialist Marina De

Liso) outplayed her as to style awareness, consistently unfolding hot

temperament and fanciful coloratura. On the contrary, both the villain

Grimoaldo (Paolo Fanale) and the arch-villain Garibaldo (Gezim Myshketa) were

absolute beginners in the field of early opera, yet delivered their fast runs

and stalking utterances pretty nicely. A further pleasant surprise was the male

alto Antonio Giovannini, who lent the loyal Unulfo mellow color, tasteful

da capos and lots of acting stamina, particularly in the alternative

E-minor version of “Sono i colpi della sorte” after the Hallische

Händel-Ausgabe (HHA).

To many affectionate Handelians, the opportunity to hear this and some more

passages restored to the composer’s final intentions was a novelty. Yet

the claim of a “world premiere in Andrew V. Jones’ critical

edition” is mere pressroom hype. The actual premiere with HHA material

before official publication was in Glyndebourne 1998, followed by the Göttingen

Händel-Festspiele in 2000 and sundry houses worldwide. Anyway, the new artistic

manager in Martina Franca, Mr. Alberto Triola, can rightfully boast for

bringing to attention a dramatic masterpiece which, despite its Italian

subject, was hitherto neglected by the major opera theaters in Italy.

Carlo Vitali

![Sonia Ganassi as Rodelinda [Photo by Laera]](http://www.operatoday.com/7133.png)