Recently in Performances

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

The doors at The Metropolitan Opera will not open to live audiences until 2021 at the earliest, and the likelihood of normal operatic life resuming in cities around the world looks but a distant dream at present. But, while we may not be invited from our homes into the opera house for some time yet, with its free daily screenings of past productions and its pay-per-view Met Stars Live in Concert series, the Met continues to bring opera into our homes.

Music-making at this year’s Grange Festival Opera may have fallen silent in June and July, but the country house and extensive grounds of The Grange provided an ideal setting for a weekend of twelve specially conceived ‘promenade’ performances encompassing music and dance.

There’s a “slide of harmony” and “all the bones leave your body at that moment and you collapse to the floor, it’s so extraordinary.”

“Music for a while, shall all your cares beguile.”

The hum of bees rising from myriad scented blooms; gentle strains of birdsong; the cheerful chatter of picnickers beside a still lake; decorous thwacks of leather on willow; song and music floating through the warm evening air.

Performances

12 Jul 2011

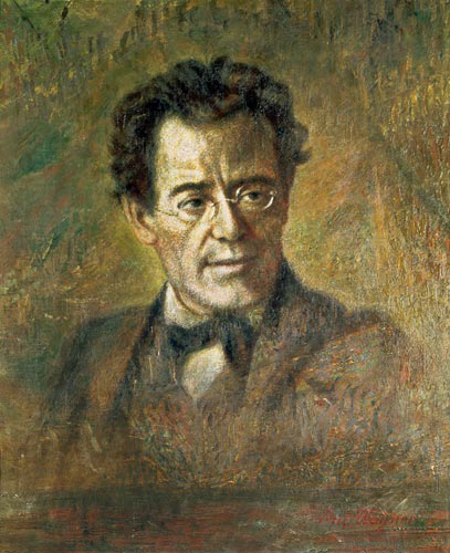

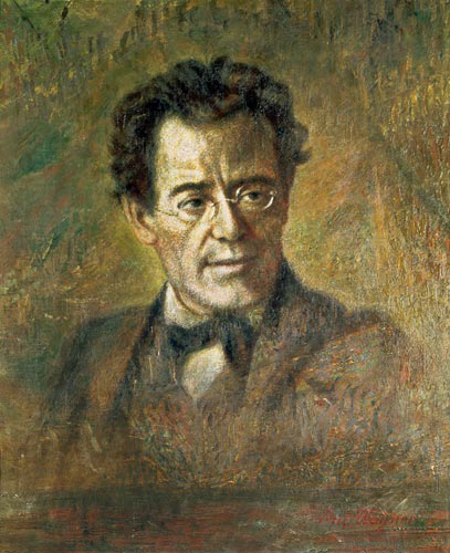

Grant Park Music Festival, Chicago Commemorates Gustav Mahler

To commemorate the hundredth anniversary of Gustav Mahler’s death Carlos

Kalmar and the Grant Park Orchestra gave in early July two performances of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde featuring the vocal soloists Alexandra Petersamer and Christian Elsner.

The work by Mahler was preceded,

fittingly, by the Musique funèbre of Witold Lutoslawski, which had

originally been composed for the anniversary of Bartok’s death and first

performed in 1958. In its performance of the latter work written for string

orchestra the Grant Park Orchestra under Kalmar gave a seamless account of the

score. The somber introduction for cellos is followed by the gradual

introduction of other string groups. A foremost impression left by these

performances is the sense of symmetry in Lutoslawski’s “memorial tribute”

as the cello ensemble returns to close the piece in an audible mirror of its

opening. The four parts of the work entitled Introduction, Metamorphoses,

Apogee, Epilogue draw on varying sound palettes for individual and groups of

sting players. After the cellos are joined by the remaining strings, tempos

increase and allow for declarative statements performed forte. This

technique used in the two middle segments of the piece is varied by sections

played piano, where the basses used gentle bowing to touching effect.

In much the same way, fragments of melodies were played by individual groups,

the full melodies then growing into a perceptible unit as tempos accelerated

forcefully. A lush, neo-Romantic transition formed the bridge to the

conclusion, or Epilogue, as Kalmar led his players toward a dignified statement

of tribute with the individual strings dissolving into the inexorable return of

the cellos.

The performance of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde followed this

memorial piece without intermission. In the first of the six vocal parts,

“Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde” (“Drinking Song of Earth’s

Misery”), Mr. Elsner sang with lyrical and dramatic force from the start, as

he gave appropriate intonation to the word “klingen” (“resound”). In

the delineation of the “Lied vom Kummer” (“song of care”) Elsner’s

emotional line was matched by the distinctive solo for oboe. Decoration was

taken here as marked with the tenor’s melisma sung on “Fülle”

(“abundance”), so that the word as performed reflected its meaning.

Starting at this point the English horn solo in this performance lent a

complementary sense of melancholy to both the voice and recurrent notes of the

oboe. The concept of eternity, which recurs memorably in the final part of

Das Lied, is here broached, as the tenor contrasts duration and

mortality in “Firmament” and “Der Mensch” (“the heavens,” “You, o

mortal”). Here Elsner’s pitch was less distinctive, as the attack on

“Mondschein” (“moonlight”) and “Gräbern” (“graves”) was sung

with greater force than suitable.

The second song, “Der einsame im Herbst” (“The Solitary one in

Autumn”), introduced the performance of Alexandra Petersamer. From the start,

the security of the singer’s range assured poignant delivery of lines such as

“Vom Reif bezogen stehen alle Gräser” (“The blades of grass stand

covered with frost”). Here Petersamer’s voice rose from stirring low notes

to a bright top with focus on “Gräser” and, with parallel approach at the

close of the strophe, on “ausgestreut” (“scattered about”). When

Petersamer began the penultimate strophe in this brief segment, she sang the

line “Mein Herz ist müde” (“My heart is weary”) with the pitch toward

flat as an illustration of this emotional state. In “Ich hab’ Erquickung

not!” (“I need refreshment!”) she engaged in what approached a dialogue

with the low strings. As a final statement of yearning “Sonne der Liebe”

(“Sun of love”) was delivered by Petersamer with full and convincingly

emotional declaration.

In the two vocal parts at the center of Das Lied both singers and

orchestra responded to the challenges of tempo in their accomplished

performances. In “Von der Jugend” (“On Youth”) Elsner showed skillful

modulation as he wrapped the vocal line around accelerated playing. Just as

Kalmar’s masterful direction eased the orchestra’s pace at “Wunderlich im

Spiegelbilde” (“Wonderfully in the reflection”), the singer’s voice

showed a matching deceleration, only to conclude this song by reversing the

technique. In her medial song, “Von der Schönheit” (“On Beauty”),

Petersamer was equally impressive as her voice imitated the “caressing

gestures” of “Schmeichelkosen” as well as the sounds of youths riding

their steeds through branches along the river’s bank. In her approach to the

last strophe of this segment she used exquisite lyrical phrasing and

piano shading to communicate the yearning of the fairest maiden

looking after the youth as he galloped away. With tasteful decoration placed on

“Sehnsucht” (“longing”) and “ihres Herzens” (“of her heart”) a

secret melancholy brought the segment to its moving conclusion.

In his last selection, “Der Trunkene im Frühling” (“The drunkard in

Spring”), Elsner contrasted the emotional opposites of toil and torment with

the happy “cheerful day” (“lieben Tag”). After sorting through issues

of volume in the initial strophe Elsner came into his own at the line “Mir

ist als wie im Traum” (“It seems to me like a dream”). At the words

“schwarzen Firmament (“dark heavens”) and “betrunken sein” (“remain

drunk”) Elsner released powerful forte notes directly on pitch to

emphasize his persona’s resolve.

As the final and longest of the six parts of Das Lied Petersamer sang “Der

Abschied” (“Farewell”) with touching clarity of tone. After the

orchestral opening during which oboe, English horn and flute hint at departure,

Petersamer’s singing merged with the instrumental soloists to echo and to

enhance their mood. Her pure, high notes on “nieder” (“downward”) and

“Schatten” (“shadows”) emphasized the words’ true meanings by

contrast of vocal line. The ghostly pitches applied to “Hinter den dunkeln

Fichten!” (“Behind the dark pines!”) evoked an evening’s solitude in

nature coupled with a desire for companionship. While delineating the

atmosphere in the forest her lowest notes were fully audible as the orchestral

texture mimicked the sounds of birds. At this point Petersamer’s

diminuendo on “hocken still” (“crouch silently”) effectively

capped the emotive setting in nature. As her declarations on beauty echoed

earlier sentiments, an orchestral interlude extended the atmosphere with

notable contributions from the woodwinds and low strings. Petersamer’s

singing concluded the piece as the “Trunk des Abschieds” (“Cup of

Farewell”) began the future thematic wandering of the departing friend. The

singer’s elaborate, meaningful decoration executed on “einsam Herz”

(“solitary heart”) illustrated along with the concluding intonations on the

repeated “ewig” (“eternally”) that this was a performance of Das

Lied von der Erde in which text and music are ideally joined, where poetry

and song receive their due when performed with such significance.

Salvatore Calomino