Recently in Performances

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

The doors at The Metropolitan Opera will not open to live audiences until 2021 at the earliest, and the likelihood of normal operatic life resuming in cities around the world looks but a distant dream at present. But, while we may not be invited from our homes into the opera house for some time yet, with its free daily screenings of past productions and its pay-per-view Met Stars Live in Concert series, the Met continues to bring opera into our homes.

Music-making at this year’s Grange Festival Opera may have fallen silent in June and July, but the country house and extensive grounds of The Grange provided an ideal setting for a weekend of twelve specially conceived ‘promenade’ performances encompassing music and dance.

There’s a “slide of harmony” and “all the bones leave your body at that moment and you collapse to the floor, it’s so extraordinary.”

“Music for a while, shall all your cares beguile.”

The hum of bees rising from myriad scented blooms; gentle strains of birdsong; the cheerful chatter of picnickers beside a still lake; decorous thwacks of leather on willow; song and music floating through the warm evening air.

Performances

14 Aug 2011

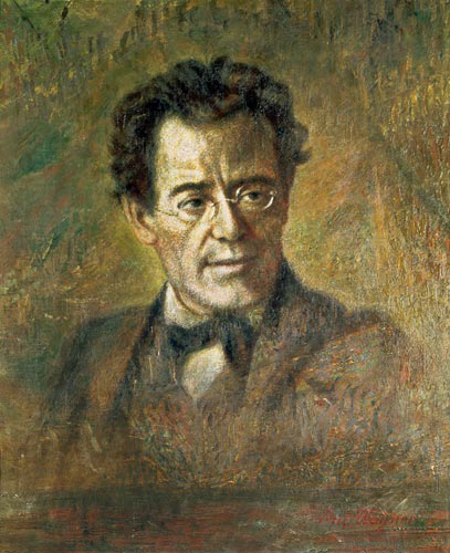

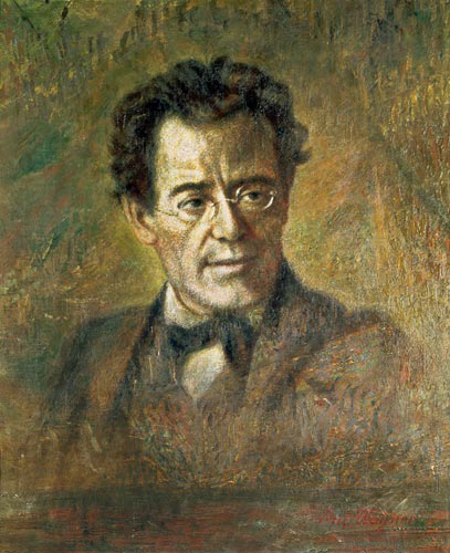

Prom 32: Brahms and Mahler

Brahms’s Violin Concerto and Mahler’s Das klagende Lied

did not seem to be the most obvious bedfellows — there has been some

rather peculiar programming at this year’s Proms — and even after

further consideration, the only real connection I could muster was that they

were written at the same time: the concerto in 1878, the cantata between 1878

and 1880.

At any rate, Christian Teztlaff gave a fine account of the former,

though he was not always matched by Edward Gardner’s conducting, which

was mostly unobjectionable — more than can be said for many examples

— but not especially rich in insight. The BBC Symphony Orchestra was

generally on good, if not infallible, form, its first movement contribution

more lyrical than stentorian. (A mobile telephone provided unwanted

interruption during the first exposition.) Teztlaff’s solo performance

was intensely committed, fiercely dramatic, and unwavering in intonation, the

cadenza (Joachim’s) providing both intimacy and direction. The opening of

the ensuing coda proved splendidly autumnal, though its conclusion was arguably

rushed by Gardner. Unwelcome applause intervened prior to a slow movement in

which Tetzlaff generally acted as first among serenade-like equals, the spirit

of Mozart undeniably present. Though the opening woodwind solos, especially

Richard Simpson’s oboe, were well taken, there was a sense that they

might have sung still more freely had Gardner moulded them less. That is a

minor criticism, however, for Tetzlaff’s sweet-toned rendition ensured

that the heart strings would be tugged where necessary, without the slightest

hint of undue manipulation. Gardner, to his credit, held the audience at bay

during the brief pause before the finale. Rhythms were well pointed here,

though there were times when the orchestra felt a little driven.

Tetzlaff’s musicianship and virtuosity were never in doubt; it would be

good to hear him in this concerto with a more experienced Brahmsian, such as

Bernard Haitink, Kurt Masur, or Sir Colin Davis. If anything even better was

his poised, thoughtful, richly expressive encore account of the Gavotte en

rondeau from Bach’s E major Partita. Not for the first time, the

smallest of forces seemed to project better than a typical symphony orchestra

in the problematic acoustic of the Royal Albert Hall.

Gardner fashioned a performance of Das klagende Lied that was more

‘operatic’ than benefits the music. Or, to put it another way, it

concentrated on highlighting of certain textual ‘incident’ and

artificially whipped-up excitement in a stop-and-start way that recalled Sir

Georg Solti (though I am not sure whether Solti conducted this particular

work). At least, though, we could hear vibrato-laden strings, a relief after

the horror tales of Sir Roger Norrington’s recent Ninth Symphony. The

orchestral introduction to ‘Waldmärchen’ was somewhat hesitant at

first, and then, as if to compensate, was fiercely driven. It eventually

settled, but the movement as a whole did not. The second stanza, though well

presented vocally and orchestrally, simply dragged, Gardner seemingly finding

it impossible to alight upon a just tempo. Uncertain brass slightly marred the

brothers’ entry into the forest, though tenor Stuart Skelton gave a good

sense of Mahler as balladeer. When, during the final two stanzas,

Mahler’s Wagnerian inheritance — Gardner seemed previously to have

done his utmost to make the composer sound closer to Verdi! — inevitably

came to the fore, whether through harmony, instrumentation, and vocal line, it

was almost a sense of too little, too late. Anna Larsson, a late substitution

for Ekaterina Gubanova, nevertheless proved a wonderfully rich mezzo

soloist.

Intimations of the First and Second Symphonies in the introduction to

‘Der Spielmann’ came across clearly — how could they not?

— but, in Gardner’s hands, there was something unnecessarily

four-square to the phrasing. Christopher Purves, however, proved plaintive

indeed upon the words ‘Dort ist’s so lind und voll von Duft, als

ging ein Weinen durch die Luft!’, even though the pacing now had become

unduly distended. The first entry of the off-stage band sounded splendid in

itself, but Gardner struggled — and failed — to keep it together

with the ‘main’ orchestra. There were, happily, no such problems

later on. Tempi here and in the concluding ‘Hochzeitsstück’ veered

towards the comatose, however, interspersed with ‘compensating’

rushed passages. What should sound wide-eyed in its staggering youthful

ambition and accomplishment tended merely to sprawl. (Applause again intervened

between the second and third movements.) Choral diction was very good

throughout, though it would have done no harm to have had a larger chorus.

Treble voices touched in their fragility, helping to prove once again that it

is this original version of Das klagende Lied that has the superior

claim to performance. I cannot begin to understand David Matthews’s

programme note claim that the revised two-part version is

‘incontrovertibly tighter and arguably more effective’. If the

effect were somewhat sprawling, that was the fault of Gardner’s

performance, not of the work itself, which is a much better piece than this

evening’s audience may have been led to believe.

Mark Berry