I imagine they were hoping that their cheerful little “singspiel”,we know as The Magic Flute would make a lot of people happy, and them a lot of money. It did both.

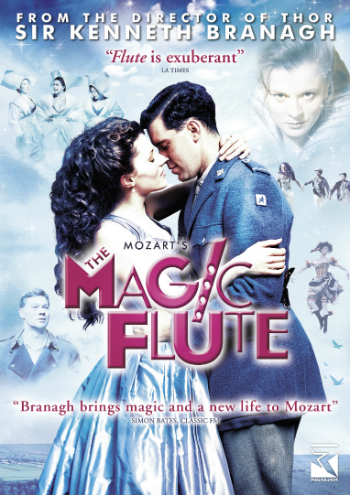

The trick of dramatizing these folktales was to keep the audience happily confused. Inexplicable things happen in inexplicable ways. Who’s good and who’s bad? You don’t find out until the end. Considering the bizarre effects telling such a tale allows, it was inevitable that the work would be brought to the screen. The first Magic Flute film, created in 1975 by the usually dour Ingmar Bergman, was a charming fantasy clearly addressed to childish pleasures. The second was created in 2006 by the Irish actor, writer, director Kenneth Branagh. The film premiered in London in 2007 to sold out audiences. It showed widely in parts of the world, and is just now being brought to the United States. It debuted here in limited showings on June 9th. 2013.

Branagh’s film is in a sense, a present day reinterpretation of The Magic Flute. To begin with, Branagh commissioned a new libretto in English from Stephen Fry. He changed the opera’s Egyptian setting to an unspecified World War I battle site. He essentially replaced the work’s Masonic symbolism with an anti-war message. And he employed the kind of magnificent technical wizardry which neither Mozart nor Shikaneder could ever have imagined.

Musical command of the work was assigned to James Conlon, Music Director of the Los Angeles Opera Company, known for his expertise in and affection for Mozart. Singers were chosen for their ability to sing English clearly and for the appropriateness of appearance, which movie goers expect. The entire opera was prerecorded. Singers lip synched Fry’s witty, rhymed text and entertaining one-liners, an excellent solution considering the number of stressful scenes. It’s unlikely that either Tamino or Pamina could have uttered much more than gasps during their trial by water.

The first scenes take us from a blue sky to a flowered meadow. Peace and happiness seem to reign. But it is short lived. The camera soon leads us to Tamino and his blue uniformed comrades hiding in trenches. But don’t worry! Branagh is quick to assure us that the film is fantasy. The soldiers are clean shaven and crisply immaculate. They are led into battle by marching troops playing violins, and their klutzy looking airplanes jerk, rather than fly. Deep in the trenches we meet Papageno, in charge of carrier pigeons and hazard warning canaries. The three ladies first turn up as flamboyant nuns, later in various other guises. In a delightful touch, Tamino’s first glance at Pamina’s portrait evokes a charming black and white ball room fantasy in the young soldier’s mind. A really, really angry Queen of the Night arrives on a tank to enlist Tamino’s aid in rescuing her kidnapped daughter. The three boys materialize at appropriate times. When we first encounter a benign looking Sarastro, he is within his huge domain devoted to kindness. It is peopled with plain looking folks and a large number of sick and maimed. The sick are in immaculate hospitals attended by clearly caring nurses. Those well enough to work are busy at various projects — coffin making for one. Sarastro too, has an army. His troops wear red.

Sarastro sings his moving “O Isis und Osiris,” a prayer that the young lovers be granted wisdom virtue and patience, overlooking what seems an endless graveyard. Behind him is a massive wall into which the names of young fallen soldiers are carved in their native languages. These include English, Hebrew, Arab, Russian and Chinese.

With 21st century film magic available to them, happily, Branagh and Fry have kept the inexplicable happenings moving at a fascinating and breakneck speed. The dizzying succession of special effects will remind you of everything from Mary Poppins to Monty Python, from Snow White to Star Wars.

Whatever the visuals, you can’t beat Mozart’s score, which is brilliantly rendered here by Maestro Conlon and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. René Pape makes a splendidly benign Sarastro opposing Lyuba Petrova’s magnificently furious Queen of the Night. Joseph Kaiser’s well acted and well sung Tamino, was appropriately heroic and tender. The role of Pamina was sung by Amy Carson, a young talented soprano, previously untested in opera. Though her well produced voice suited the lighter moments in the score, it lacked the heft for its dramatic arias. Benjamin Davis and Sylvia Moi were delightful as Papageno and Papagena. The fantasy offspring Branagh supplied them during their engaging duet, added to the joyous scene. Tom Randle was humorously menacing Monastatos. Credit Kenneth Branagh that every role, large and small, whether sung or not, was extraordinarily well acted.

In an interview Branagh gave in 2009, he expressed concern about how opera fans would receive his work. “I know that some Mozart fans will turn up their noses at these changes, but this film is not designed for them, I’m trying to tell the story as if it were new, for a new audience.”

I believe that Branagh is correct and hope he finds his audience. I found the film literally too dark hued, too crowded with people, and too action packed. But then, I’m a veteran of decades of opera house Magic Flutes, and prefer it set as a more graceful fantasy. In truth, I must tell you that other, perhaps younger reviewers described the film differently. “Fresh and spectacular,” wrote one. “Branagh’s imagery is imaginative and the music lifts you,” said another. Still another declared himself “enamored of the work.”

Kenneth Branagh’s Magic Flute is unique in the history of movie making and opera. It’s worth seeing for the experience itself and perhaps to explore your own preferences in fantasy.

I saw the film on a readily available DVD that features interviews with Kenneth Branagh, his cast the crew, and a “making of” featurette.

Estelle Gilson

Cast and production information:

Tamino: Joseph Kaiser; Pamina: Amy Carson;Papageno: Ben Davis; Papagena: Sylvia Moi: Queen of the Night: Lyuba Petrova; Sarastro: René Pape; Monastatos: Thomas Randle. Director: Kenneth Branagh. English Libretto: Stephen Fry. Music Director and Conductor: James Conlon. Chamber Orchestra of Europe. Production Design: Tim Harvey.