Upon its rediscovery near the

end of the 19th Century, Monteverdi’s score fell victim to ‘improvements’

by many hands, the efforts of which were mostly inspired by recognition of the

quality of the score to endeavor to span the chasm separating modern musical

values from the performance practices of the mid-17th Century. Esteemed

composers Vincent d’Indy, Ernst Krenek, Carl Orff, and Gian Francesco

Malipiero prepared editions of the opera, and Sir Michael Tippett presided over

a scholarly effort at editing the score at Morley College. It was the 1962

production prepared by Raymond Leppard for the Glyndebourne Festival that

reintroduced L’Incoronazione di Poppea to 20th-Century music lovers,

its accomplished cast—including Richard Lewis, Magda László, Frances Bible,

Walter Alberti, Carlo Cava, Lydia Marimpieri, Oralia Dominguez, John

Shirley-Quirk, and Hugues Cuénod—recorded for posterity by EMI.

Leppard’s edition of the score arranged Monteverdi’s delicate

instrumentation, ever subject to debate owing to lingering uncertainty about

the precise complement of instruments for which Monteverdi’s score was

written, for a large modern symphony orchestra; at Glyndebourne and on EMI’s

recording the Royal Philharmonic under the baton of Sir John Pritchard. Like

most of its few contemporaries, the Glyndebourne production also transposed

several important rôles for singers whose genders matched those of their

characters rather than the vocal ranges indicated in Monteverdi’s score.

Nerone, likely first sung by a soprano castrato, thus became a tenor,

and the alto rôle of Ottone was reassigned to a baritone. Though musically

far removed from any notion of authenticity, the Glyndebourne recording offered

several exceptional performances that revealed the great beauty, variety, and

dramatic vitality of Monteverdi’s music: the tonal allure and sensuality of

Magda László’s Poppea, the dignity of Carlo Cava’s Seneca (in what may be

the finest recording of his career), the histrionic power of Frances Bible’s

Ottavia, and the standard-setting Lucano of Hugues Cuénod all contributed to a

considerably abridged recording that now sounds like a bloated fossil from an

operatic Stone Age but remains an enjoyable example of legitimate efforts to

marry good voices with great music. It was not until Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s

pioneering 1974 recording that a credible attempt was made at restoring

L’Incoronazione di Poppea to something resembling what

Monteverdi’s audiences might have heard in Venice in 1643 or in Naples in

1651, during what is believed to have been the only revival of the opera until

the early 20th Century. Staged productions of the opera—notably the 1963

performances at the Wiener Staatsoper conducted by Herbert von Karajan,

benefiting from the radiant Poppea of Sena Jurinac—were slow to follow

Harnoncourt’s example until the historically-informed performance practice

movement was firmly established throughout Europe. After the publication of

American conductor Alan Curtis’s edition of the score, which sought to

preserve fidelity to the surviving Venice and Naples manuscripts to the

greatest extent possible, productions have increasingly utilized versions of

the opera that honor musicological concepts of period-appropriate performance

values in terms of instrumentation and vocal styles. If some early efforts at

presenting L’Incoronazione di Poppea in an historically-sensitive

manner resulted in fragile musical qualities that seemed effective only in the

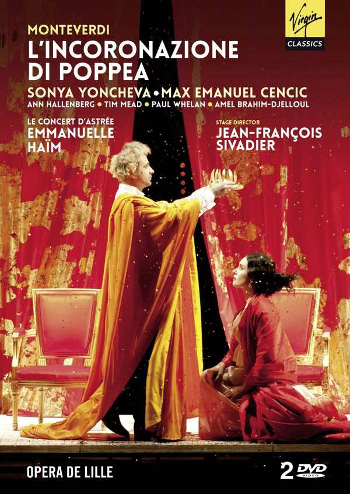

settings of small Baroque theatres, this production by Jean-François

Sivadier—taped by Virgin Classics during performances at the Opéra de Lille

in March 2012—proves that Monteverdi’s opera, even when performed on period

instruments, is the equal of the greatest masterpieces in the operatic

repertory and is capable of being produced effectively in any theatre in the

world.

Mr. Sivadier’s production plants L’Incoronazione di Poppea

firmly in a world of decadence, aestheticism, casual morals, and recreational

sex used as a weapon in political turf wars. Superbly enhanced by scenic

designs by Alexandre de Dardel, lighting by Philippe Berthomé, and gorgeous

costumes by Virginie Gervaise (not to be confused with French adult film star

Virginie Gervais, whose presence would be strangely appropriate in this

deliciously sexy production), Mr. Sivadier refines his extensive experience in

French lyric theatre and opera—including a psychologically thrilling

production of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck—into an organized but

enthrallingly ambiguous account of Monteverdi’s score. Perhaps the most

intriguing dramatic aspect of the opera is the composer’s portrait of his

title character: one of the most duplicitous figures in Roman history, as

ruthless in pursuit of her ambitions as any Emperor or Senator, Poppea is

shaped by Monteverdi with music of almost ethereal beauty. No other operatic

heroine of such cruelty conducts her conspiracies more attractively. The

nastiest sentiments in Giovanni Francesco Busenello’s libretto are set by the

composer to the most extraordinarily captivating music. Mr. Sivadier’s

production explores this dichotomy entrancingly, portraying Poppea as a

sociopathic manipulator who calculatingly exploits every tic of Nerone’s

neuroses. Considering the opera merely as a series of emotional exchanges

removed from their specific historical context, L’Incoronazione di

Poppea is—like the plays of Shakespeare—surprisingly modern.

Paranoia, cheating spouses, rampant narcissism, and obsession are all as

central to Monteverdi’s opera as to any 21st-Century novel or film. Mr.

Sivadier explores all of these elements in his production without in any way

distorting Monteverdi’s finely-crafted drama, sharpening the opera’s edge

while avoiding damaging its 17th-Century patina. There are manic moments in

the production, but it cannot be denied that L’Incoronazione di

Poppea is not populated by completely sane people. Mr. Sivadier’s

gifts for creating edge-of-the-seat, meaningful theatrical experiences are

validated in this production, in which there are strokes of genius.

As too many performances in the past half-century have proved, even the most

innovative production falls flat when musical values do not keep pace with the

dramatic ventures. Having gone all in with Mr. Sivadier’s production,

Opéra de Lille matched the magnificent dramatic qualities with the

trend-setting musical values of Emmanuelle Haïm and Le Concert d’Astrée.

An acknowledged mistress of Early Music and Baroque opera, Maestra Haïm brings

dynamic instincts for thoughtful shaping of Monteverdi’s music to this

production of L’Incoronazione di Poppea, her fidelity to presumed

notions of authentic instrumentation never standing in the way of adroit

exploration of the textures of sound possible with period instruments. None

of the players in Le Concert d’Astrée displays anything less than absolute

virtuosity, and the musical quality of the recorded production is nothing short

of incredible. Thankfully, Virgin Classics’s engineers, guided by Philippe

Béziat, have avoided problems of balance that can imperil the distinctive

sounds of period instruments, placing the performance within a recorded

acoustic that suggests a natural theatrical space but also fosters an exemplary

blend between stage and pit. L’Incoronazione di Poppea is a long

night at the theatre, but Maestra Haïm keeps the performance moving without

rushing or adopting tempi that are quick solely for the sake of

brevity. Joining with Mr. Sivadier and the production team, Maestra Haïm and

Le Concert d’Astrée lay a foundation upon which a talented cast can build a

memorable L’Incoronazione di Poppea.

With singers as gifted as musicians and actors as Nicholas Mulroy, Mathias

Vidal, Patrick Schramm, Aimery Lefèvre, Camille Poul, Khatouna Gadelia, and

Anna Wall in secondary rôles, this production immediately offers a richness of

casting that is virtually impossible in a production of any Verdi, Wagner,

Strauss, or Puccini opera today. An artist of proven excellence, Mr. Mulroy

brings his engagingly plangent tenor voice to all of the parts that he sings in

this performance. His unerring dramatic instincts and superb musicality are

matched by the fantastic tenor Mathias Vidal, whose bravura Lucano is

a worthy successor to the legacy of Hugues Cuénod, and promising young bass

Patrick Schramm. Baritone Aimery Lefèvre joins rambunctiously into the

spirit of the production, his singing as Mercurio especially animated.

Soprano Camille Poul sings attractively as Amore and the Damigella. The

exotic young soprano Khatouna Gadelia makes the most of every line she sings as

la Virtù and the Valletto. Fortuna, Venere, and Pallade benefit from the

lovely voice and lively stage presence of mezzo-soprano Anna Wall.

Moroccan countertenor Rachid Ben Abdeslam, whose Metropolitan Opera début

as Nireno in the Company’s first presentation of the celebrated David McVicar

production of Händel’s Giulio Cesare garnered praise from both

audiences and critics, is in this production of L’Incoronazione di

Poppea a commanding presence as the Nutrice, the elderly nursemaid of the

rightful Empress Octavia. The voice is a vibrant instrument, and Mr. Ben

Abdeslam brings unexpected depths of feeling to the Nutrice’s words of

comfort to the disenfranchised Ottavia. Equally impressive as one of the

followers of Seneca, he is a consistently gripping actor and energetic singer

in this performance. Another singer of North African extraction contributes

beguilingly to the production: Algeria-born soprano Amel Brahim-Djelloul offers

an intriguingly wide array of emotions in her performance as Drusilla, her

trials endured with dignity and a sense of dedication to making the most of her

destiny. A very attractive young woman with an endearingly expressive command

of stage motion, Ms. Brahim-Djelloul bears Drusilla’s betrayal with

integrity, the voice poised and freely-produced even in moments of greatest

emotional stress.

The Swiss-born son of Chilean parents, tenor Emiliano Gonzalez Toro is an

accomplished performer of the unique haute-contre rôles in Baroque

opera. Possessing a technique that enables him to sing even the most

demanding music without worry, Mr. Gonzalez Toro has carefully honed his skills

as an actor. The humor that he brings to his performance as Arnalta,

Poppea’s nurse, is broad but understated: without conveying condescension to

the spirit of his travesti rôle, Mr. Gonzalez Toro reveals the innate

absurdity of having an older woman sung by a male singer. This respects

Monteverdi’s handling of this convention of his time, of course, and Mr.

Gonzalez Toro is a pleasingly shy presence as the wilting nurse.

Surprisingly, Arnalta was blessed by her composer with one of Monteverdi’s

most enchantingly comely melodic inspirations, ‘Oblivion soave,’ the

so-called lullaby sung to the uneasy Poppea. The passage is no easy sing for

a tenor, the artist’s command of the tessitura notwithstanding, but

Mr. Gonzalez Toro sings it winningly.

It is easy to understand the mindsets of editors of L’Incoronazione di

Poppea who transposed the rôle of Ottone from Monteverdi’s original

contralto register to baritone range. In addition to making the opera more

palatable for modern audiences by having characters sing with voices that

adhere to conventions of how they should sound, with male characters having

men’s voices, making Ottone—and Nerone, for that matter—a rôle for an

‘ordinary’ male voice mitigates a preponderance of high voices in the

opera. There can be little doubt that Monteverdi created a sound world in

which Seneca was the only deep-voiced principal character with very deliberate

intentions, however, and musicians who approached L’Incoronazione di

Poppea in the early years of its renaissance did not have today’s crop

of good countertenors at their disposal. Few performances of the opera have

enjoyed an Ottone as fine as British countertenor Tim Mead, whose centered,

focused voice aligns with acting that gets at the heart of the character.

Facing misfortune and rejection, Ottone’s character is not entirely

unblemished: he, too, engages in artifice, all too willingly accepting

Drusilla’s affection for his own benefit when he is keenly aware that his

heart pines only for Poppea. Mr. Mead reflects this duality convincingly in

his performance, coloring the voice intelligently and summoning dulcet tones

for Ottone’s most heartfelt utterances, not least in his first scene. A

lithe, handsome performer, Mr. Mead interacts with his colleagues

fascinatingly, his Ottone generating great chemistry with Ms.

Brahim-Djelloul’s Drusilla. Mr. Mead’s voice is genuinely beautiful, and

the sincerity of his performance makes Ottone an unusually looming presence in

the opera.

Youth is not a quality that is typically associated with Seneca, the

legendary philosopher and tutor having been in his mid-sixties at the time of

his death. New Zealand-born bass-baritone Paul Whelan is a young singer, but

he wisely allows the low tessitura of Monteverdi’s music for Seneca

to depict the character’s age and wisdom rather than adopting any sort of

embarrassing attempts at aged frailty. History suggests that Seneca was

likely innocent of Nero’s charges of complicity in an assassination plot, but

Monteverdi’s point in giving Seneca’s forced suicide such a prominent place

in the drama—and in having the dazzlingly difficult coloratura duet

of celebration for the drunken Nerone and Lucano follow hard on its heels—is

that morality cannot survive in a world such as that inhabited by Nerone and

his court. Mr. Whelan plausibly enacts this sense of Seneca against the

World, and the gravitas with which he sings Seneca’s death scene is

commanding but not unduly heavy. While other, older, darker-voiced singers

have conveyed greater mystery and hoary unflappability in the rôle, Mr.

Whelan’s performance—unimpeded by unnecessary posturing,

creatively-phrased, and firmly-voiced—is completely successful on its own

terms.

The technique of Swedish mezzo-soprano Ann Hallenberg is a wonder of nature,

her mastery of even the most dizzying coloratura equaled by her

ability to project long arcs of lustrous tone in cantilena. In her

performance of Ottavia in this production, she also proves to be a tragedienne

of unimpeachable serenity. The daughter of the Emperor Claudius, a cousin of

Caligula, and a descendent of Tiberius, Claudia Octavia was the first wife of

Nero and the rightful Empress regnant: unsettled by her inevitable involvement

in the power struggles between Nero and his mother, Agrippina, she was an

upright, moral woman. It is not surprising that Nero quickly tired of her.

If Poppea was the Wallace Simpson of Imperial Rome, Ottavia was its Queen

Mother: unbending and courageous even in the face of great adversity and

danger, she won the hearts of Romans and was passionately mourned when she,

too, was forced to ritualistic suicide. Ms. Hallenberg’s singing wins the

hearts of the Lille audience, the stylishness of her execution of

Monteverdi’s music providing moment after moment of fire and tenderness.

The passion of her reaction to Nero’s rejection brings to mind the intensity

of Maria Callas and Leyla Gencer in the scene in which Henry VIII orders the

rightful Queen’s imprisonment and trial in Donizetti’s Anna

Bolena. Ms. Hallenberg’s Ottavia is deflated but audibly never

defeated by the machinations that deprive her of her throne, and any sense of

bitterness or contempt is dispelled by her heartbreakingly beautiful

performance of ‘Addio, Roma,’ the scene in which she laments her impending

exile from her beloved Eternal City. Knowing that she is capable of almost

unbelievable feats of vocal virtuosity, Ms. Hallenberg touches the heart most

viscerally in this performance with her moments of lyrical quietude. Her

music leaves no doubt that Ottavia engaged Monteverdi’s sympathy: Ms.

Hallenberg’s performance permits no question of the importance of Ottavia as

a musical ancestor of the most affecting tragic heroines in opera.

Nero has one of the most unflattering and contentious legacies in history.

Maligned by many historians, some of whom have suggested that Rome collectively

rejoiced in his death, other scholars—both ancient and modern—argue that

Nero has been unfairly criticized and made a scapegoat for the unsavory

politics that festered in Rome during his reign. Mostly overlooking his less

attractive qualities, Monteverdi portrays Nerone as a lover whose sense of

morality is secondary to his chasing of carnal pleasure. Unbecomingly

bewigged but a swaggeringly masculine, libidinous participant in the drama,

countertenor Max Emanuel Cencic is the arrogant, hormonal Emperor to the

life. The boundless energy with which Mr. Cencic portrays Nerone admits no

doubt that his thinking is mostly done in his trousers, but the glorious

singing makes it clear that this Emperor’s richest treasures are in his

throat. Mr. Cencic’s voice is unlike those of many countertenors, his

timbre deep and more conventionally operatic: completely absent are the

hootiness familiar from the singing of many countertenors and the clumsy

register breaks that undermine the best efforts of even very good

falsettists. There are occasional moments of concern when it seems that Mr.

Cencic pushes his upper register hard, but the results are unfailingly exciting

and put to vivacious dramatic use. Like Ms. Hallenberg, Mr. Cencic is a

celebrated practitioner of bravura singing, and his delivery of the

coloratura in Nerone’s duet with Lucano—‘Hor che Seneca è

morte, cantiam’—is breathtaking. His come-hither tones lend his

performance a steamy eroticism that is complemented by his frenetic acting, his

Nerone slinking through the performance with the sleazy charm of a playboy

known in every house of ill repute in Rome. The tessitura of Nerone

is high for a countertenor, but Mr. Cencic, whose voice has a slightly higher

center of vocal gravity than those of many of his counterparts, has all of the

notes comfortably in the voice. There are moments of luminously beautiful and

restrained singing even in this impetuous performance, and Mr. Cencic makes

Monteverdi’s ornaments sound completely natural. With a DECCA recording of

the rôle of Andronico in Händel’s Tamerlano scheduled for release

in October, 2013 is poised to be another year of tremendous success for Mr.

Cencic. Based solely on his singing of Nerone in this performance of

L’Incoronazione di Poppea, Mr. Cencic’s importance as a singer is

indisputable.

Supported by a cast of such distinction, young Bulgarian soprano Sonya

Yoncheva more than holds her own as a determined, irresistibly tantalizing

Poppea. A woman with Hollywood starlet looks and curves, Ms. Yoncheva has

engagements as Donizetti’s Lucia and Verdi’s Violetta on her horizon, and

her Poppea might be viewed as a study for both rôles. Spinning out golden

tones from start to finish, it is hardly astonishing that her Poppea should so

captivate Ottone or so arouse Nerone. Costumed like a Jean Harlow vixen, Ms.

Yoncheva exudes sex appeal, her hold on Nerone developing as surely as though

she were Salomé performing the Dance of the Seven Veils before Herod.

Physical beauty, alert acting, and capable singing are rarely as absorbingly

combined in a single performance as in Ms. Yoncheva’s Poppea. Perhaps

Monteverdi intended his portrait of Poppea as a sly commentary on the power of

a pretty seductress to triumph over goodness, her misdeeds forgiven and

forgotten as soon as she smiles. In Poppea’s toying with Nerone and Ottone,

her triumph might also be interpreted as a victory of lust over love, though

here, too, a musical problem is encountered: ‘Pur ti miro, pur ti godo,’

the concluding duet for Poppea and Nerone, though almost certainly not the work

of Monteverdi (modern scholarship suggests the little-remembered Benedetto

Ferrari as the most likely candidate for having composed both the music and the

text), is unabashedly beautiful. If truly not the work of Monteverdi, it was

almost certainly appended to L’Incoronazione di Poppea either by the

composer himself or with his blessing [the duet is present in autograph

materials of both the Venice and Naples versions of the opera], so it is

possible that the apparent celebration of the triumph of scheming, the text of

the duet ripe with subtle sexual undertones, was at least partially

intentional. Ms. Yoncheva’s and Mr. Cencic’s voices intertwine like a

lovers’ embrace in the duet, closing the opera in an atmosphere of relative

dramatic calm and sensual release. Visually and musically, Ms. Yoncheva

leaves nothing to be desired, her performance as Poppea the proper centerpiece

of a potent account of Monteverdi’s opera.

With its complex relationships, destructive sexual politics, and crumbling

social orders, Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea is as

psychologically momentous as any of Wagner’s operas. Nerone shares with

Wotan the dubious distinction of being a man of absolute but dwindling power

with both a strong wife of noble birth and a roving eye. Like all the best

works of art, Monteverdi’s opera is both decidedly of its specific time and

place and definitively universal. Recordings of L’Incoronazione di

Poppea on DVD are no longer rare, but this version from Virgin

Classics—a record of what is without question one of the best-sung

productions of the opera in its history—can be jubilantly crowned the best of

the lot.

Joseph Newsome

Claudio Monteverdi (1567 - 1643): L’Incoronazione di

Poppea—S. Yoncheva (Poppea), M. E. Cencic (Nerone), A.

Hallenberg (Ottavia), T. Mead (Ottone), P. Whelan (Seneca), A. Brahim-Djelloul

(Drusilla), R. Ben Abdeslam (Nutrice, un famigliare di Seneca), E. Gonzalez

Toro (Arnalta), A. Wall (Fortuna, Venere, Pallade), K. Gadelia (Virtù,

Valletto), Camille Poul (Amore, Damigella), A. Lefèvre (Mercurio, Console), P.

Schramm (un famigliare di Seneca, Littore), M. Vidal (Soldato, un famigliare di

Seneca, Lucano), N. Mulroy (Soldato, Liberto capitano, Tribuno); Le Concert

d’Astrée; Emmanuelle Haïm [Recorded in March 2012 during performances at

the Opéra de Lille; Virgin Classics 9289919; NSTC, Region Code 0]

[This review was first published at Voix

des Arts. It is reprinted with the permission of the author.]