03 Aug 2013

Coleridge Taylor: The Song of Hiawatha, Three Choirs Festival

The Song of Hiawatha, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor at Gloucester Cathedral, highlight of this year's Three Choirs Festival.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

The doors at The Metropolitan Opera will not open to live audiences until 2021 at the earliest, and the likelihood of normal operatic life resuming in cities around the world looks but a distant dream at present. But, while we may not be invited from our homes into the opera house for some time yet, with its free daily screenings of past productions and its pay-per-view Met Stars Live in Concert series, the Met continues to bring opera into our homes.

Music-making at this year’s Grange Festival Opera may have fallen silent in June and July, but the country house and extensive grounds of The Grange provided an ideal setting for a weekend of twelve specially conceived ‘promenade’ performances encompassing music and dance.

There’s a “slide of harmony” and “all the bones leave your body at that moment and you collapse to the floor, it’s so extraordinary.”

“Music for a while, shall all your cares beguile.”

The hum of bees rising from myriad scented blooms; gentle strains of birdsong; the cheerful chatter of picnickers beside a still lake; decorous thwacks of leather on willow; song and music floating through the warm evening air.

The Song of Hiawatha, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor at Gloucester Cathedral, highlight of this year's Three Choirs Festival.

The Three Choirs Festival is the world's oldest music festival. For over three hundred years, the choirs of the cathedrals of Gloucester, Hereford and Worcester have been coming together to sing.

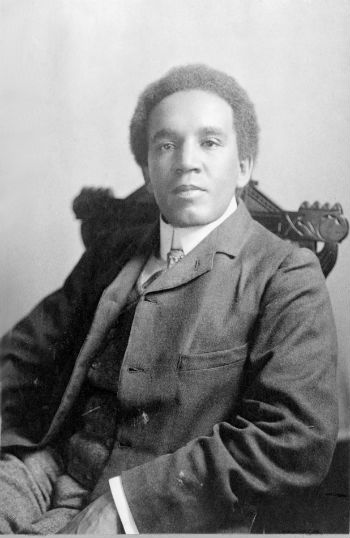

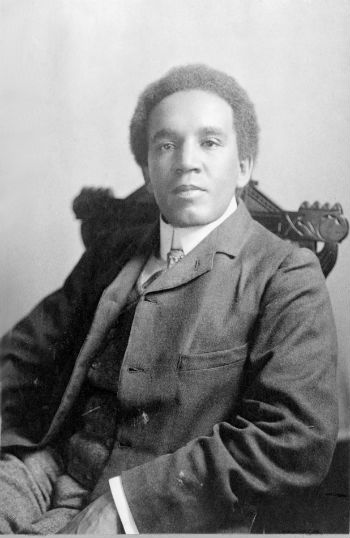

In many ways, British music was defined by the Three Choirs Festival well into the mid 20th century: it is the epicentre of a grand tradition. Hearing Coleridge-Taylor's Hiawatha in Gloucester Cathedral was significant, because the Festival was instrumental in bringing the composer to prominence. While still a student, Coleridge-Taylor came to the attention of Alfred Jaeger and Edward Elgar. The Three Choirs Festival gave him his first big commission in 1897, on the express recommendation of Elgar. Hiawatha's Wedding Feast followed soon after, then the full Song of Hiawatha we were privileged to hear. By the age of 25, Coleridge-Taylor was a resounding success.

Coleridge-Taylor is sometimes called "The Black Mahler" but it's a silly marketing gimmick. It's musically illiterate. Coleridge-Taylor didn't conduct opera and didn't write symphonies. The Song of Hiawatha sits firmly in the oratorio tradition. If anything, Coleridge-Taylor was the "Black Elgar". The Three Choirs Chorus sang with such fervour that the Elgarian aspects of the score shone with great conviction, even if the words were a little indistinct. But what joy it must have been for them to tackle this strange, almost hypnotic chant, and words like Pau-puk-Keewis, Chibiabos, Shaugodaya, Kuntassoo and Iagoo! Hiawatha is a Grand Sing and needs to be done on this grand scale.

The soloists stand forth from the chorus. Twenty years ago, Bryn Terfel sang the baritone part for the Orchestra of the Welsh National Opera, under William Alwyn. He was brilliant, defining the whole piece with his presence, all the more striking because he sounded so young, No-one could compare, though Benedict Nelson did his best. Robin Tritschler sang the tenor part, negotiating the cruelly high cry "Awake ! my beloved" with ease. Hye-Youn Lee sang the soprano part with exceptional freshness and vitality. She's a singer we should be hearing a lot more of.

Orchestrally, The Song of Hiawatha is rousing. London's Philharmonia Orchestra played for Peter Nardone as if they were playing grand opera. The horn call that introduces the piece and runs throughout suggested Wagner. Both Siegfried and Hiawatha are Noble Savages, setting out on voyages of discovery. The pounding timpani, however, suggest the type of drums white people assumed Red Indians would play. They also anchor the orchestra in a way percussion would not perhaps control symphonic form for many years to come. The Song of Hiawatha is oratorio, but also influenced by new European influences. Englishmen didn't really write opera until Peter Grimes in 1948. The Philharmonia were much livelier and more vivid than the WNO Orchestra on the recording.

Although Hiawatha hands his people over to missionaries to be civilized, it doesn't sit well with the pious religious values of its time. Even Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius, completed two years after Hiawatha's Wedding Feast, was considered racy in many circles because of its Catholic connections. But Hiawatha is important, not just for its exotic subject. Coleridge-Taylor may have chosen Longfellow's text because of its unique syntax, imitating the repetitive chant of oral traditions. "By the shores of Gitchee Gumee, by the shining Big Sea Water". Even the strange names come over like incantation. For a musician, this syntax translates into musical form. Coleridge-Taylor adapts the syntax into short rhythmic cells. Coleridge is experimenting, tentatively, with new form. How he would have responded to Stravinsky, to Picasso, to Diaghilev and to Ravel!

There are lyrical passages in Hiawatha that evoke the freshness and wonder of Dvorák's Symphony From the New World, written only five years before, and definitely "new" music. Yet Coleridge-Taylor's style is distinctively his own. At this stage, Vaughan Williams, though slightly older, was still under the thumb of Charles Villiers Stanford and Delius was yet to find himself. Unlike, say, Granville Bantock, whose exoticism operated like fancy dress costume, Coleridge-Taylor absorbed alien ideas into his very artistic core. He listened to Black American music and adapted to create something original. Years later Bartók would turn to Hungarian folk music to create new music, but Coleridge-Taylor was well on the way earlier. Perhaps he was attracted to Black music as a kind of atavistic quest for identity, since he never knew his father. But every time he looked in the mirror he must have been reminded that part of who he was remained a mystery. Vaughan Williams's later discovery of English folk song seems very tame in comparison.

When Coleridge-Taylor collapsed and later died, on Croydon Railway Station in 1912, aged only 37, British music lost a true original, perhaps, even, its greatest hope after Elgar. Although he should not be judged by the colour of his skin, it's an inescapable part of what he means to us today in multicultural Britain. He's probably also influential in the United States where he was welcomed into the White House by the President, at a time when blacks entered only by the back door. When Coleridge-Taylor was born in 1875, being illegitimate was scandalous. Even though he wasn't "deprived", and there weren't enough Black people around for prejudice to develop beyond curiosity, Coleridge-Taylor would have had to live with other people's stereotypes, however veiled. So I hope we'll be able to get away from the British music ghetto and the "Black Mahler" cliché and respect Coleridge-Taylor in a wider music and social history context.

Coleridge-Taylor's The Song of Hiawatha from The Three Choirs Festival will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3 in September.

Anne Ozorio