This is a (forgive the pun) grave, serious Don Giovanni. Although

Mozart wrote to his father that ‘The most essential thing is that on the

whole the story should be really comic’, the phrase ‘on the whole’ leaves

room for some equivocation and the term dramma giocoso has given the

musicologists much to chew over. (Indeed, the esteemed Mozart scholar Tim

Carter titles his programme article ‘Serious, Comic Or…’)

But, if the overall effect of the production is somewhat sombre, and the

ending leaning towards existential, then the action itself is full of life, the

stone-grey façade of Es Devlin’s inventive set illuminated by the engaging

video animations of Luke Halls and Bruno Poet’s lighting design.

Alex Esposito as Leporello

Alex Esposito as Leporello

As the foreboding tones of the introductory andante are swept aside by the

overture’s Molto Allegro onward scurrying, so the curtain rises on a

bare exterior wall, imposing facing the auditorium. But, it doesn’t stay bare

for long; like a visual representation of the musical narrative, the names of

Don Giovanni’s sexual conquests appear — at first slowly then in a frantic

rush of calligraphic etching. It is as if an invisible pen of light is

reproducing before our eyes the inscriptions in the Don’s catalogue of

paramours.

As the central cube of Devlin’s architectural design rotates, a

doll’s-house labyrinth of staircases reaching into perpetuity and

interlocking rooms for lovers’ trysts, washes of colourful graffiti —

patterns and petals, tears and tessellations — tell the Don’s tale. In the

second act the side panels of the façade draw back, isolating the

geometrically intricate cube within a black void and emphasising the Don’s

loneliness. It’s all visually engaging and thought-provoking, the

disorientating vortex which accompanies the ‘Champagne aria’ — with

Giovanni suspended at the centre of the geometric maelstrom — is a highpoint,

suggesting both the effervescent fun of popping of champagne corks and the

uncontrollable consequences of the reprobate’s debauchery.

The mid-nineteenth century costumes (by Anja Vang Kragh) are handsome —

the ladies’ frocks are especially luxurious and eye-pleasing — but they

fail to communicate the class differences which drive the conflict, most

noticeable with the vengeful interlopers at the wedding party cry, ‘Viva la

libertà!’

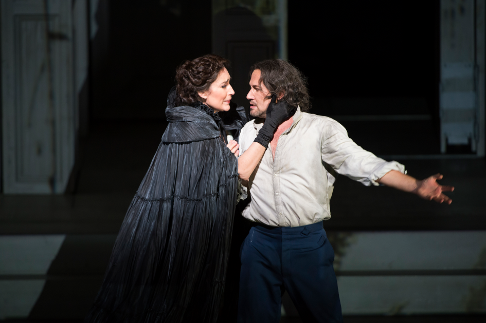

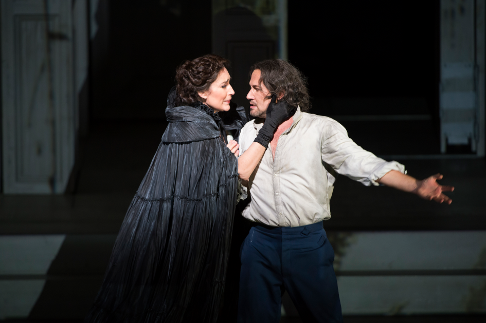

Veronique Gens as Donna Elvira and Mariusz Kwiecień as Don Giovanni

Veronique Gens as Donna Elvira and Mariusz Kwiecień as Don Giovanni

Mariusz Kwiecień’s Don is more pensive quester than glib libertine or

irrepressible rake, but his poise and good looks are effortlessly charming. His

rich baritone is even and flexible, and complemented by a beautiful silky tone

— showcased in a wonderful ‘Serenade’. Not surprising, then, that the

woman are bewitched: who wouldn’t be charmed by the eloquent elegance of

Kwiecień’s ‘Là ci darem la mano’?

Certainly, Donna Anna is in his thrall. Sung with unfailing power (a little

too much at times?) by Swedish soprano Malin Byström, this Donna is a woman

who knows her own mind, what she wants and how to get it. It’s clear from the

opening moments that she is hot for Giovanni as he is for her; as her loyal

Ottavio declares his adoration in ‘Dalla Sua Pace’ — “What pleases her

gives life to me … joy I cannot know unless she shares it” — his tenders

words are mocked by his betrothed’s heartless actions: Anna climbs the

staircase for an assignation with the expectant, colluding Giovanni.

Byström was committed but sometimes the brightness of tone had a harder

edge, and her Italian diction needs some work. That said, she more than

mastered the technical challenges.

Véronique Gens’ Donna Elvira couples ardent passion with resentful fury.

Although Gens offered an impassioned ‘Mi tradi’ — a fiery denouncement of

the perfidious betrayer — with superb breath-control and dynamic variation,

Elvira remained determined to believe the best (or ignore the worst) of the man

who has deceived her. As Leporello recited the catalogue of inamoratas, she

clutched Giovanni as if the warmth of her embrace might erase the evidence from

the page. Gens’ stylish ornamentation was also exemplary.

Malin Byström as Donna Anna and Mariusz Kwiecień as Don Giovanni

Malin Byström as Donna Anna and Mariusz Kwiecień as Don Giovanni

Leporello was expertly sung and acted by Italian bass-baritone Alex

Esposito, the above-mentioned catalogue aria suave and stylishly phrased. The

sleazy servant’s roguery was credible and his vulnerability to the whims of

his untrustworthy master touching. Esposito is fast making a name for himself

as a consummate Mozartian — especially in this role — and it was a shame

that the production does not offer more opportunity for him to showcase his

skills as a master of musical comedy and irony.

Powerful, well-crafted singing from Italian tenor Antonio Poli gave stature

to Don Ottavio, a character who can sometimes be over-shadowed by the charisma

of his adversary and the hysterics of his affianced. ‘Dalla sua pace’ was

particularly sweet of tone, and a delicately floated pianissimo was

bestowed with heart-rending poignancy by the concurrent betrayal of his

false-hearted Anna.

Elizabeth Watts’s Zerlina is no unworldly country girl; lively and

vivacious, she is eager to submit to Giovanni’s advances — although it

isn’t clear why, having succeeded in evading Masetto’s watchful

surveillance, she should then felee from Giovanni’s embrace, tearing her

dress to suggest an assault? Last minute doubts, or simply a tease? Watts’s

voice was sumptuous but always polished; Dawid Kimberg’s Masetto, despite

showing his potential for violent outburst when delivering Zerlina a vicious

clout in a fit of jealousy, was no match for her guile in ‘Batti, batti’.

Kimberg himself sang with attractive tone, musically precise and verbally

crisp.

Making his house debut, Ukrainian bass Alexander Tsymbalyuk was impressive

as the Commedatore. Although presented as a fabrication of Giovanni’s

increasingly disorientated imagination, Tsymbalyuk — positioned aloft, above

the figure of an eye — projected with commanding impact into the auditorium,

dignified and intent on justice.

A scene from Don Giovanni

A scene from Don Giovanni

At the helm conductor Nicola Luisotti led the orchestra of the Royal Opera

House vivaciously through the score; oddly, the brightness and grace of the

orchestral playing was not matched by Luisotti’s own rather heavy-handed

fortepiano-continuo, which was overly loud, flamboyantly intrusive and

inappropriately dissonant at times.

It was a pity that such a large cut was deemed appropriate in the final

scene. But, the conclusion itself was powerful: rather than the customary

flames of damnation and desperate descent to Tartarean depths, Holten and

Devlin fade to grey, the light and colour of life withdrawing, leaving Giovanni

alone, arms-outstretched, uncomprehending. As the fugal chorus — much

truncated — assails him from the wings, Giovanni is an isolated, confused

figure, unable to make sense of a world indifferent to his experiences,

recognising that the freedom he has enjoyed brings inescapable consequences.

Not a defiant nihilist, rather a man yearning for life: this

dissoluto is certainly punito.

Claire Seymour

Cast and production information:

Don Giovanni, Mariusz Kwiecień; Leporello, Alex Esposito; Donna

Anna, Malin Byström; Donna Elvira, Véronique Gens; Don Ottavio, Antonio Poli;

Zerlina, Elizabeth Watts; Masetto, Dawid Kimberg, Commendatore, Alexander

Tsymbalyuk; conductor, Nicola Luisotti; director, Kasper Holten; set designs,

Es Devlin; video designs, Luke Halls; costume designs, Anja Vang Kragh;

lighting designs, Bruno Poet; choreography, Signre Fabricus; fight director,

Kate Waters; orchestra and chorus of the Royal Opera House. Royal Opera House,

Covent Garden, Saturday 1st February 2014.

![Mariusz Kwiecień as Don Giovanni [Photo © ROH / Bill Cooper]](http://www.operatoday.com/DON_GIOVANNI-RO_487.png)