These are the folks who brought down the 2003 Aix Festival after disrupting the opening night La traviata, and are threatening to bring down the current Aix and Avignon festivals, the crown jewels of estival high art in France. Recognizing the periodic nature of employment for workers in theatrical arts, including cinema, the French government awards the intermittants unemployment compensation well above that provided unemployed workers in fields that offer permanent employment.

This enlightened and much abused program of the French state subsidizes the ferment of the theatrical arts in France by allowing technicians and artists to pursue careers in theater rather than by forcing them to seek careers in fields that provide full employment. The Aix and Avignon festivals are the most vulnerable battlefields for working through the inevitable fiscal and political tensions created by such a program.

All of the intermittents of the Aix Festival filled onto the stage at a bit after 7 PM last night (July 2, opening night), one of whom read a brief, dignified statement about the contribution of the intermettents to French arts. The audience applauded and they filed off, not delaying the performance sufficiently to allow those of us who arrived mistakenly at 7:30 for an 8 pm curtain to catch the first act.

Never mind, Act II is the masterpiece act. It was a great pleasure to be able to enter the auditorium, finally, the chorus seated in a spread out auditorium fashion facing us (the audience) on the bare, black stage. Sarastro walked through the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra (seated house level) mounted the podium to deliver the Masonic creed in a precious, very precious German (like you might use to speak to idiots). This address was on what is called the “God” microphone (the microphone held by the stage director during the final theater rehearsals) that reverberates in volumes only known to overpowering deities (stage directors). It was an impressive trick. Promising.

Trail by Water to sound effects (not to music)

Trail by Water to sound effects (not to music)

The production, by London theater personality Simon McBurney, was first done last winter at the English National Opera in the English language. What may have been real words (in English) to a British audience became cute, caricatured Germanic sounds for a very French audience in very French Aix that enclosed the entire production (well, the second act) within quotation marks — Die Zauberflöte quoting itself. Add this to Mr. McBurney’s highly self conscious theatrical vocabulary — all scenic effects were physically performed in miniature on one side of the stage and projected onto the stage backdrop, all sound effects (multitudinous) were physically created in miniature on the other side of the stage and amplified throughout the hall. The presence of theatrical manipulation was overpowering.

Mr. McBurney and his collaborators have a fecund recollection of advanced theater vocabulary, virtually every avant-garde gimmick that has been over-used in theater crazed Berlin over the past 30 or so years found its way onto the Grand Théâtre de Provence stage during the next hour or so, very long hour or so. The few very fine moments of theatrical success — the opening Act II council, the Queen of the Night’s Act II wheelchair aria ("Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen"), Tamino and Papageno’s final encounter with the Three Ladies, and the choreographic shapes created in the final chorus unfortunately did not contribute to a comprehensible exposition of the philosophy of this masterpiece.

McBurney’s Flute set out to amaze and amuse. On this level it well succeeded with the opening night audience. However Mozart’s massive singspiel was never intended to be an ordinary little entertainment for the Viennese hoi polloi of yesteryear or the Parisian haute bourgeoisie of today. It set out to exemplify the encompassing nobility and the eternal importance of the Masonic process, not to make theatrical fun out of it. Die Zauberflöte was completely forgotten in McBurney’s theatrical gluttony. But no matter, the audience was impressed and the powers that be of the Aix Festival are pleased as Punch.

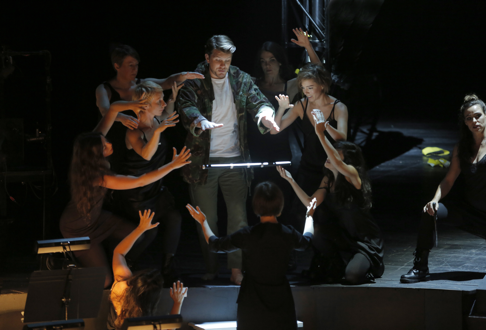

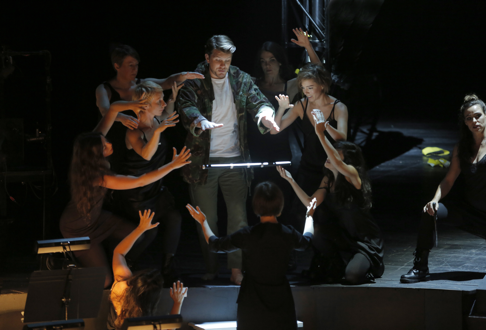

Presentation of the flute by members of the orchestra

Presentation of the flute by members of the orchestra

Bernard Foccroulle (foe-crew-yeh), general director of the Aix Festival is committed to co-productions as a cost-cutting measure. Therefore any production you now see in Aix may not be specific to the time (now) and place (Aix). In this case Mozart’s Flute was created last year by an Englishman for an English audience. What then remains to make the Aix Flute a production of the Aix Festival is the cast, chorus, conductor and orchestra.

It is a prestigious festival. Its efforts to assemble the musical personnel are intelligent, interesting and far-reaching. The Flute cast reached perfection in the Pamina of young Norwegian soprano Mari Eriksmoen with just the right blond look who possesses of voice of pure tone befitting of the purity and innocence of Mozart’s heroine. The same may be said of young French tenor Stanislaus de Barbeyrac who found the perfect balance of innocent manhood and enlightened aspiration.

Papageno was Dutch baritone Thomas Oliemans who was given so much business on the stage and within the audience that his presence was irritating to those of us (surely there were at least a few of us) who did not buy into Simon McBurney’s onslaught. This included a virtuoso level keyboard performance by Mr. Oliemans on a keyboarded glockenspiel, an imagined version of an instrument Mozart included but of which no example has survived.

The balance of the cast from around Europe and the U.S. were handsome singers, very ably fulfilling their requirements. German bass Christof Fischesser as Sarastro suffered the indignity of competing with the very loud, extraneous sound effects McBurney added to the Sarastro scenes. The contrast between these volumes and the natural acoustic of Mr. Fischesser’s voice rendered, by comparison, his arias too softly delivered to be impressive.

The three boys, named only as soloists of the Knabenchor der Chorakademie Dortmund, were big, finished performers who grandly did McBurney’s bidding of turning the purity of young boys into instruments of the Queen of the Night’s chaos.

Freiburg’s famed baroque orchestra (Freiburger Barockorchester) was in the pit bringing spectacular colors to Mozart’s transcendental music. The 32 youthful voices of Britain’s English Voices created a magnificently clear, beautifully pure and very loud "Die Strahlen der Sonne" (the final chorus). Spanish conductor Pablo Heras-Casado presided over the occasional periods the production allowed the Mozart score to take over. His efforts to make an impression then became too obvious. Even so, there were many splendid musical moments.

Mr. McBurney skipped in to take his bows in jeans, a shirt carelessly (wanna bet) tucked in, and a baseball cap worn backwards. Cool, very cool.

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Tamino: Stanislas de Barbeyrac; Pamina: Mari Eriksmoen; Queen of the Night: Kathryn Lewek; Papageno: Thomas Oliemans; Papagena: Regula Mühlemann; Sarastro: Christof Fischesser; Monostatos; Andreas Conrad; Erste Dame: Ana-Maria Labin; Zweite Dame: Silvia de La Muela; Dritte Dame: Claudia Huckle; Der Sprecher: Maarten Koningsberger; Erster Priester/Zweiter Geharnischter: Krzysztof Baczyk; Zweiter Priester/Erster Geharnischter: Elmar Gilbertsson. English Voices (chorus) and the Freiburger Barockorchester. Conductor: Pablo Heras-Casado; Mise en scène: Simon McBurney; Décors: Michael Levine; Costumes: Nicky Gillibrand; Lumière: Jean Kalman; Vidéo: Finn Ross; Sound: Gareth Fry. Grand Théâtre de Provence, July 2, 2014.

![Kathryn Lewek as Queen of the Night [Photo by Pasal Victor courtesy of the Aix Festival]](http://www.operatoday.com/Flute2_Aix1.png)