It was a production by Jean-Paul Scarpitta who was stage director and scenery and costume designer. Mr. Scarpitta’s dramaturgy is informed by his fascinations for Giorgio Strehler and Robert Wilson from which many wonderful stagings have resulted during his ten year residency in Montpellier.

There was promise in the air, the breadth of the raked stage (300 feet wide, 60 feet deep) was covered in a black asphalt-like substance, the mostly intact, imposing scaenae frons (back wall of the theater) was bare, overseen from high above by the massive sculpture of the Emperor Augustus. The revelation of the evening was the lighting of the black floor by Urs Schônebaum, its enormous shiny, rough surface shone in a myriad of intensities for the huge exterior scenes, sometimes it was reduced to a brilliant square of white light to frame a singer (Nabucco’s intensely personal “Son pur queste mie membra”), other times strong directional side light cast enormous, elongated shadows across the stage that deepened emotional relationships (the Act I confrontation of Abigail with the lovers Fenena and Ismaele).

Scapitta’s staging of Verdi’s early masterpiece was sabotaged often by the video projections on the back wall. After an initial appreciation of the technical feat of accomplishing such massive projections (ranging from discretely deployed white-lighted, descending emotional shapes to the ugly, yellow-ish, sprayed styrofoam image that covered the entire back wall for the palace interior scenes) the projections became distractions to the accomplishments of the singers and lights on the black floor.

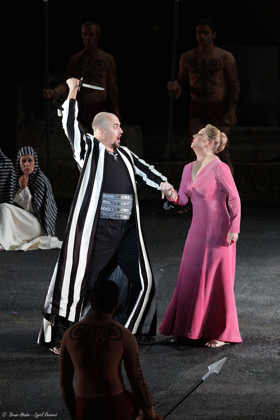

George Gagnizde as Nabucco, Maria Serafin as Abigail

George Gagnizde as Nabucco, Maria Serafin as Abigail

Mr. Scarpita is a musical stage director, his actors moved more by musical line and musical structural rather than by dramatic motivation. Here too he was sabotaged, now by singers who were read as static lumps of color rather than as the excited singers responding to the young Verdi whose Nabucco revealed his genius for the first time.

Veteran Georgian baritone George Gagnizde made some big sounds in a strong entrance but soon fell into an almost lieder-like performance by a bored singer. Veteran Austrian soprano Maria Serafin, a noted Tosca, no longer has the bloom of voice and perhaps never had the agility of voice to create a vibrant Abigail, a character Verdi created to tear-up-the-stage vocally and dramatically.

Younger members of the cast were more effective. French mezzo-soprano Karine Deshayes made a low key Fenena that conveyed a static presence and personality in her monochrome rose costume. Italian tenor Piero Pretti sang a stylish Ismaele and moved gracefully.

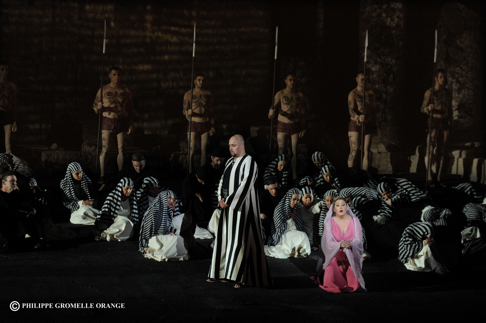

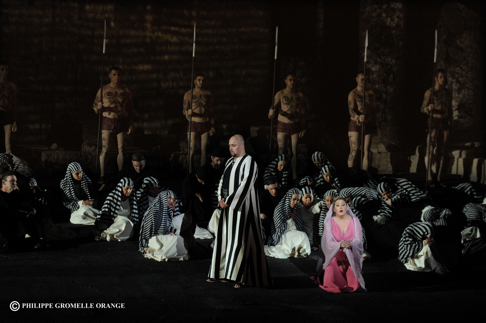

Dimitry Beloselskiy as Zaccaria, Karine Deshayes as Fenena.

Dimitry Beloselskiy as Zaccaria, Karine Deshayes as Fenena.

The opera is however about Nabucco and Abigail, not Fenena and Ismaele. Russian bass Dimitry Beloselskiy made it about the Jewish high priest Zaccaraia as well. This fine young bass found the voice and presence to make his role the biggest performance of the evening. Unfortunately his performance was sabotaged by his costume, a white robe covered by black lightning bolt-like (sort of) shapes. While the powerful shapes on the costume sought to embody a force of divine strength they instead made his exhortations seem decorative rather than dramatic.

The costumes of the chorus were always identical, creating giant blocks of color on the stage, mostly static swathes of color that in theory (and if they were far larger) might have become a pedal-point musical color. The problem of how to move these blocks of color onto and off of the stage was never overcome. An additional scenic impulse backfired — thirty or so spear carrying Babylonian warrior extras wearing only loin clothes. Had these stalwart young Orangeois been clothed they might have seemed handsome and strong. Semi-nude they exposed a variety of shapes and postures that cried out for prosthetic chests.

The sight lines from the cavea (the tiered seating) of the Théâtre Antique makes the orchestra (seated in the “orchestra” of a Roman theater) a visually important part of the field of vision. This presence together with the fine acoustic of the theater leaves the orchestra as exposed as a solo singer on the stage. Here the unforgiving acoustic revealed the weaknesses of the Orchestre National de Montpellier, particularly the winds, The sound of the orchestra itself lacked the finesse expected of a fine French orchestra.

The conducting of veteran Israeli maestro Pinchas Steinberg did not come near the intense excitement that Verdi had found within himself for opera as a patriotic art form, nor for the new styles of vocal virtuosity that Verdi asked of his singers. Even “Va pensiero” came across as little more than a self-conscious hum along.

And what about the lighted, window onto upstage stage center from back stage that was left uncovered? Its light and passing figures fouled the stage picture of anyone sitting in Section 4. Is there no one home at the Chorégies?

Michael Milenski

Casts and production information:

Abigaïlle: Martina Serafin; Fenena: Karine Deshayes; Anna; Marie-Adeline Henry; Nabucco: George Gagnidze; Zaccaria: Dmitry Belosselskiy; Ismaele: Piero Pretti; Il Gran Sacerdote di Belo: Nicolas Courjal; Abdallo: Luca Lombardo. Orchestre National Montpellier Languedoc-Roussillon. Choruses of the opera companies of Nice, Montpellier, Avignon and Toulon. Conductor: Pinchas Steinberg. Mise en scène, scenery and costumes: Jean-Paul Scarpitta; Lighting: Urs Schönebaum. Théâtre Antique Romain, Orange, France, July 9, 2014.