25 Aug 2014

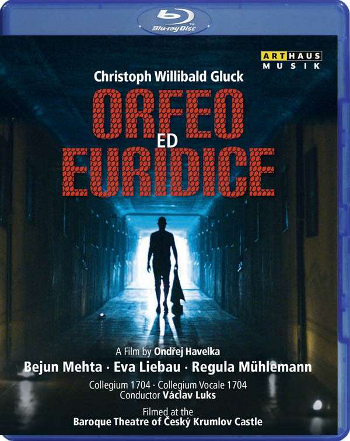

Gluck: Orfeo ed Euridice

This elegant, smartly-paced film turns Gluck’s Orfeo into a Dostoevskian study of a guilt-wracked misanthrope, portrayed by American countertenor Bejun Mehta.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

The voices of six women composers are celebrated by baritone Jeremy Huw Williams and soprano Yunah Lee on this characteristically ambitious and valuable release by Lontano Records Ltd (Lorelt).

As Paul Spicer, conductor of the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire Chamber Choir, observes, the worship of the Blessed Virgin Mary is as ‘old as Christianity itself’, and programmes devoted to settings of texts which venerate the Virgin Mary are commonplace.

Ethel Smyth’s last large-scale work, written in 1930 by the then 72-year-old composer who was increasingly afflicted and depressed by her worsening deafness, was The Prison – a ‘symphony’ for soprano and bass-baritone soloists, chorus and orchestra.

‘Hamilton Harty is Irish to the core, but he is not a musical nationalist.’

‘After silence, that which comes closest to expressing the inexpressible is music.’ Aldous Huxley’s words have inspired VOCES8’s new disc, After Silence, a ‘double album in four chapters’ which marks the ensemble’s 15th anniversary.

A song-cycle is a narrative, a journey, not necessarily literal or linear, but one which carries performer and listener through time and across an emotional terrain. Through complement and contrast, poetry and music crystallise diverse sentiments and somehow cohere variability into an aesthetic unity.

One of the nicest things about being lucky enough to enjoy opera, music and theatre, week in week out, in London’s fringe theatres, music conservatoires, and international concert halls and opera houses, is the opportunity to encounter striking performances by young talented musicians and then watch with pleasure as they fulfil those sparks of promise.

“It’s forbidden, and where’s the art in that?”

Dublin-born John F. Larchet (1884-1967) might well be described as the father of post-Independence Irish music, given the immense influenced that he had upon Irish musical life during the first half of the 20th century - as a composer, musician, administrator and teacher.

The English Civil War is raging. The daughter of a Puritan aristocrat has fallen in love with the son of a Royalist supporter of the House of Stuart. Will love triumph over political expediency and religious dogma?

Beethoven Symphony no 9 (the Choral Symphony) in D minor, Op. 125, and the Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. 80 with soloist Kristian Bezuidenhout, Pablo Heras-Casado conducting the Freiburger Barockorchester, new from Harmonia Mundi.

A Louise Brooks look-a-like, in bobbed black wig and floor-sweeping leather trench-coat, cheeks purple-rouged and eyes shadowed in black, Barbara Hannigan issues taut gestures which elicit fire-cracker punch from the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

‘Signor Piatti in a fantasia on themes from Beatrice di Tenda had also his triumph. Difficulties, declared to be insuperable, were vanquished by him with consummate skill and precision. He certainly is amazing, his tone magnificent, and his style excellent. His resources appear to be inexhaustible; and altogether for variety, it is the greatest specimen of violoncello playing that has been heard in this country.’

Baritone Roderick Williams seems to have been a pretty constant ‘companion’, on my laptop screen and through my stereo speakers, during the past few ‘lock-down’ months.

Melodramas can be a difficult genre for composers. Before Richard Strauss’s Enoch Arden the concept of the melodrama was its compact size – Weber’s Wolf’s Glen scene in Der Freischütz, Georg Benda’s Ariadne auf Naxos and Medea or even Leonore’s grave scene in Beethoven’s Fidelio.

This elegant, smartly-paced film turns Gluck’s Orfeo into a Dostoevskian study of a guilt-wracked misanthrope, portrayed by American countertenor Bejun Mehta.

The filmis sung, played, danced and staged in a style not inappropriate to the day of the opera’s premiere in 1762 on the stage of the Baroque Theatre of Český Krumlov in the Czech Republic—or in the theater’s wings, stairs and basement, doing service for Orfeo’s journey to the Underworld.

Aside from the soloists, the forces involved are all Czech. Collegium 1704 is an early-instruments ensemble led by Václav Luks. He and the band perform on early instruments, wearing proper uniforms and white wigs. Zdenek Flemming’s sets reproduce eighteenth-century models, using appropriate stage machines: roiling surf, descending clouds, fluttering birds; a formal Italian garden for Elysium, a palatial interior for the conclusion. Andrea Miltnerova’s choreography is of the era. Jana Zborilova’s costumes go rather overboard “Goth” for the chorus of Furies but are otherwise such as Gluck might have seen. The lighting wittily illuminates the action, character and text. The director, Ondřej Havelka, moves swiftly from scene to scene, focusing tightly on his singers (excellent actors all), with gentle ribbing of baroque convention—for instance, having Amor (the charming Regula Mühlemann) file his nails with an arrow, then use it to cut the rope with which Orfeo attempts to hang himself.

Mehta, also credited as “Artistic Advisor,” is the focus of the entire show, even his scruffy beard-style being replicated by most of the male chorus. In the original (Vienna, 1762) version of the opera, which is used here, the piece is almost a monodrama, its simple story unadorned with the subplots, comic relief, showpiece arias of no point to the story that had been the rule in opera hitherto. We focus here almost entirely on Orfeo’s emotions and the deeds that grow out of them. When Amor descends in her flying cloud to coax Orfeo on his quest, he seems stunned, as if he sees nothing, as if this entire “revelation” is internal. The tacked-on happy ending demanded by Empress Maria Theresa delights Eva Liebau’s Euridice, but Orfeo is disgusted and goes off in a sulk to sit by himself in the theater seats, observing. (The happy ending has always seemed bogus to me: Do we really get our loved ones back from death if only we love them enough? I don’t think so. But that’s what is implied.)

It seems to be the theory of Mr. Havelka that the entire story is a hallucination occurring in the head and heart and psyche of an Orpheus wracked with guilt. Apparently (we learn in a “dumb show” flashback) he has murdered Eurydice, who was jealous of his music and attempted to take his lyre. With such perfect musical forces to pass the brief time span (75 minutes), we may ignore the more puzzling subplots thus implied. Apparently Orpheus desires Eurydice’s return not simply for love but to make amends for a deed that drives him mad; when she does return, triumphantly, he departs alone, in disgust. I found this unsettling, but it certainly solves the problem created by the happy ending. The casual viewer, however, may be so won over by the beauty of the film and the score, so delighted with the singing, as to ignore the psychological twists and turns imposed on the plot.

Mehta sings with a bright, lustrous sheen and a prevailing melancholy color that are most attractive, never hooting or forcing beyond his natural and exceptional strength. His torment as Eva Liebau’s Euridice doubts his sincerity is personal and persuasive, and his musicality includes charming ornaments of the da capo of “Che faró senza Euridice.” The ladies have a great deal less to sing but do it lavishly, with sweet voices and elegant line.

John Yohalem

Recording details:

Liebau, Mühlemann, Mehta; Collegium 1704, Luks. A film by Ondřej Havelka, filmed in the Baroque Theatre of Český Krumlov Castle. Arthaus Musik Blu-ray 108 103. 75 mins. In Italian, subtitles in six languages.